Bicentenary of St. Mary's

Belfast

How NOT to Celebrate the Bicentenary of a Catholic Church

by Francis Gallagher

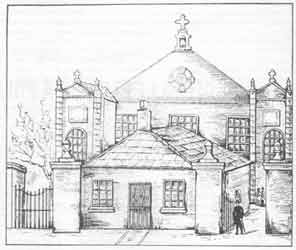

Belfast's first Catholic church. The original St. Mary's, built 1783.

|

Earlier this year we published a series of articles by Michael Davies dealing with the destruction of Catholic sanctuaries by liturgical vandals claiming to act in the name of Vatican II. The article which follows is a sad one. It comes from Belfast in Northern Ireland, and describes the manner in which Bishop Cahal Daly of the Diocese of Down and Connor destroyed the Catholic ethos of St. Mary 's, the oldest Catholic Church in Belfast.

|

THE ALTAR IS, almost literally, the cornerstone of Catholic worship. In Pope Paul's New Mass, Michael Davies points to its significance as "the focal point of the whole liturgy; it is the raison d'etre of the building in which it stands. The church exists for the altar, not the altar for the church."1

Altars and sacrifice have always been integral to Judeo-Christianity, and indeed to most religions, Protestantism being something of an exception. In the Old Testament Noah erected an altar on emerging from the ark and God ordered Jacob to build Him an altar at Bethel. To Moses God said: "Seven days shalt thou expiate the altar and sanctify it: and it shall be most holy" (Exodus XXIX, 37). In the New Testament St. Paul teaches: "We [Christians] have an altar whereof they have no power to eat who serve the tabernacle" (Hebrews XIII, 10).

The earliest Christian churches were built around the tombs of martyrs which had long been serving as altars, hence the custom of placing relics of martyrs in altars. The Catholic Encyclopedia (1911) informs us: "Mass may sometimes be celebrated outside a sacred place but never without an altar, or at least an altar stone." St. Sixtus II (257-9) is said to have been the first to prescribe that Mass should be celebrated upon an altar.

The sixteenth-century reformers wasted no time in attacking the altar. Thus we had the notorious statement from Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London, in 1550: "The form of the table shall more move the simple from the superstitious opinions of the popish mass unto the right use of the Lord's supper. For the use of an altar is to make sacrifice upon it; the use of a table is to serve for men to eat upon."2 Although mischievous attempts have often been made to portray St. Paul as a proto-Protestant the reformers conveniently forgot his admonition: "What have ye not houses to eat and drink in? or despise ye the church of God and put to shame them that have not?" (I Cor. XI, 22). That the reformers did indeed despise the House of God was shown by their frenzied orgy of altar and sanctuary wrecking coupled with a systematic campaign of propaganda.

The enforcement of the reformers' diktats in Ireland, still stubbornly Catholic in the early eighteenth century, was attempted through the notorious penal laws which deprived Catholics of virtually all their political and economic rights. The clergy faced particularly heavy penalties including the possibility of death. Fr. Phelim O'Hamill a "popish priest" responsible for the Belfast area, who was ordained by the martyred St. Oliver Plunkett, died in Belfast jail. As all the surviving churches were commandeered by the established (i.e., Protestant Church, Catholics had literally to take to the hills in order to worship in relative freedom from the unwelcome attention of the authorities.

In these circumstances the altar was truly "the focal point of the whole liturgy." Worshippers were prepared to endure the elements or the roughest of shelters provided they had altars where they could assist at Mass. These took the form of what came to be affectionately and respectfully known as "Mass rocks"—many of which still dot the Irish countryside.

In Belfast Mass was celebrated at Stranmillis on the city's outskirts. In the words of a local ballad:

|

In penal times as peasants tell, |

On holy days, when Mass attendance attracted less attention, it was possible to have Mass in a private house near the city center. From 1769 it was said in a crude and dirty Mass house which was approached through the colorfully and appropriately named Squeeze Gut Entry. By 1782, when Belfast's Catholic population had reached a thousand and the penal laws were being relaxed somewhat, the parish priest, Fr. Hugh O'Donnell, acquired a lease on a site in Crooked Lane (now Chapel4 Lane) for the purpose of building a church. Apart from the greater physical hardships and the fact that persecution came from outside the institutional Church, the story so far of Belfast Catholicism is similar to that of many of today's Tridentine Mass groups.

On arriving to say the first Mass in St. Mary's on the 30th of May 1784, Fr. O'Donnell was greeted by a guard of honor composed of the mainly Presbyterian Volunteers. Although the political and economic motives behind Protestant friendliness towards Catholics in Belfast at this time have often been played down by sentimental Catholic, Nationalist and Liberal historians, there was nevertheless much genuine good will between the two communities. This was expressed in a donation of eighty-four pounds and a gilt mahogany pulpit to St. Mary's from Belfast Protestants.

According to Dr. Patrick Rogers: "The new church was by no means an imposing structure. Its design had obviously suffered from the prohibitions5 laid down in the relief act of 1782 as well as from the influence of the style of ecclesiastical building in the neighborhood—with the result that in general appearance St. Mary's resembled an old-fashioned Presbyterian meetinghouse."6 To correct this somewhat the architect had been lavish in his display of crosses. In 1868 Belfast's "mother church" was reconstructed in a more Romanesque style. There were further renovations in 1941.

The parish has been depopulated by development and St. Mary's is now used mainly by city center workers and passing shoppers. Nevertheless its historical significance for Belfast remains. This was neatly summarized in 1955 by the then local bishop, Dr. Daniel Mageean:

St. Mary's is symbolic of the Mass, for the more dignified celebration of which it was erected. "It is the Mass that matters," said Augustine Birrell;7 and to the Catholics of the penal times as to their descendants of the present day, the Mass was the focus of their thought and action. The Mass is the center of Catholic life, and in the evolution of "Old St. Mary's" from its unimpressive structure of 1784 to the present beautiful church we see typified not only the continuity of this life but its virility and expanding influence.8

St. Mary's was symbolic of the fidelity of Belfast Catholics to the Mass.

Obviously, therefore, Belfast Catholics should have good reason to celebrate St. Mary's Bicentenary on the 30th of May, 1984. How, they asked themselves, would the Diocese of Down and Connor mark this auspicious occasion? The answer, when it came on August 11, 1983, revealed how much things had changed since Dr. Mageean's time, never mind that of Fr. O'Donnell. Under the headline "Church facelift sparks anger," The Irish News reported:

Angry parishioners have described alteration work to St. Mary's Church as "an act of vandalism."

"They have taken away the pulpit and two side altars as well as removing the altar rails and they've erected a platform which looks like pop groups should be performing on it," one man complained.

The parishioner, who did not wish to be named, said he had attended St. Mary's, the oldest Catholic church in Belfast, all his life and he was "appalled" by the changes and by the fact that parishioners were being kept in the dark about what was going on.

"All they told us was that one o'clock Mass would be suspended for three weeks while alteration work was being carried out and the usual 9 a.m. Mass would be put back to 8:15.

"They told us nothing about what changes were to be made," he continued, "I understand that according to the Second Vatican Council parishioners were to be kept better informed. But they have treated us like a bunch of semi-literate peasants.

"Naturally there are a lot of rumors flying about in the absence of any proper information. The pulpit which was donated by a group of local Presbyterians9 has been taken away and we don't know if it is coming back again."We are very angry about the whole thing," he said. "This has always been called 'Old St. Mary's' and it would be a complete act of vandalism to try to modernize it."

Experience elsewhere has of course shown that dictating to the "unrenewed" laity, rather than increased consultation, is characteristic of the "Conciliar Church."

It is instructive to compare this with Dr. Rogers's account of the 1941 renovations:

What pleases many of the priests and people who have visited St. Mary's during the progress of the work, is that while the church has been reconditioned and renovated, it is still "Old St. Mary's." The position of the high and side altars has not been altered. Much of the old high altar has been retained, and even the columns which originally formed a canopy at the back of the old altar have been re-used at the entrance doors into the sacristies. The old wrought iron Communion rails are again in position . . . (My emphasis)10

Many other important relics of St. Mary's past were also preserved. The work was carried out slowly and laboriously in order to avoid interfering with Masses, Confessions and other important events. But then all this was before Vatican II.

The Irish News report also carried the "official" account. According to a spokesman for the diocese, "alterations to the church were necessary to bring it into line with liturgical changes announced at the Second Vatican Council in 1965." The changes "would involve bringing the altar further forward to be closer to the congregation." The two side altars were to go "as they belong to the time when priests did not concelebrate Mass." The work was "long overdue since changes to church design were announced twenty years ago." He alluded to changes already effected in other local churches and then added ominously: "We are also looking at St. Peters"—in Belfast, I hasten to add! "I can appreciate that people are worried," he concluded, "but we take great care to preserve the character of the churches. Nothing would (sic) be done to change the very special atmosphere of St. Mary's which everyone who visits it appreciates." Like the sixteenth-century reformers, today's liturgical commissars couple their vandalism with reams of glib propaganda.

In an effort to counter the spokesman's arguments, I pointed out, in a letter published by The Irish News on August 15th, that changes like those at St. Mary's "were certainly not authorized by Vatican II. Article 124 of the Liturgy Constitution merely includes the recommendation that 'when churches are to be built let great care be taken that they be suitable for the celebration of liturgical services and for the active participation of the faithful.' (My emphasis.)" I pointed out that there was nothing here nor in the rubrics of the Novus Ordo about tampering with altars. I added that I was not impressed by the diocesan spokesman's reassurances. Already one church had been used for a rock concert and several others now looked more like Quaker meeting houses. "The parishioners of St. Mary's," I concluded, "are right to be angry and disturbed." There was, of course, no reply from the diocesan authorities.

Yet our ultra-"ecumaniacal" bishop, Cahal B. Daly, is far from being the silent type. Indeed he exults in extravagant displays of his own psuedo-poetic version of "Vatican Twospeak." He bares his soul to us as follows:

| Christianity is not about explaining the world, But about changing it. It is not about explaining human existence, But about making us new creatures.11 |

Obviously His Lordship's extensive library of the works of Teilhard de Chardin is not being allowed to lie fallow.

Of course, it is possible that like the oracles and prophets of Greek drama our bishop feels that a veneer of "poetry" cushions the impact of bad news—like the continuing introduction of endless liturgical innovations. Thus we have his ode to Communion in the hand:

|

Since the Vatican Council, |

Revealing how hand Communion was imposed through "legalizing" lawbreaking would doubtless upset the rhythmic pattern of this veritable masterpiece. William McGonagall!13 thou shouldst be writing at this hour. Bishop Daly craves your laurels!

However, when a friend wrote to our bishop to inquire why St. Mary's was being so deplorably vandalized he received no reply, poetic or otherwise. The Muses were also absent when I challenged him repeatedly concerning the legality of the Tridentine Mass. Finally his secretary informed me: "The bishop wishes to point out to you that the decision of the Holy See on the matter of the Tridentine Mass is quite clear and binds all Catholics—bishops as well as laymen. This is the only comment the Bishop wishes (sic) or indeed can make concerning the matter." My subsequent reply (23 Feb. 1984) suggested that by not mentioning the Pope, His Lordship was implicitly admitting that he who alone can ban the Tridentine Mass had not done so. This time there was no reply. Perhaps our bishop is busy working on an epic poem, describing the liturgical revolution for the ICEL14 Book of English Verse.

Of course Bishop Daly has his trusty "diocesan spokesman" on hand to "explain" what was happening. He appeared again in The Irish News issue which carried my letter. This time he was named. Enter, Father Gerry Patton, Press Officer for the Diocese of Down and Connor, and, like others of his ilk, a doyen among progressivists. According to Fr. Gerry, St. Mary's would be "modified but not tastelessly modernized." The parishioners' fears were "understandable" but were "based on misinformation." St. Mary's would retain its traditional character but the alterations would "help it serve the celebration of the liturgy as promulgated (sic) by the Second Vatican Council," and they would "make the church still more intimate (!) and prayerful than generations of worshippers have found it in the past." He explained, according to the report, that "the altar would be brought forward slightly, closer to the congregation, and the whole sanctuary would be raised on a fully carpeted (!) platform and extended a little beyond the present position of the altar rails . . . This would improve visibility and help the participation of the congregation in the Mass." The side altars would only be partially removed and the Marian altar would be replaced by a more beautiful Marian shrine. The tabernacle would be given full prominence. All "precious links" with St. Mary's historic past including the gilt pulpit would be preserved. Fr. Patton insisted, finally, that judgment should not be passed until the work was completed.

One writer to The Irish News (August 23, 1983) was not prepared to wait. After saying he "felt numb" that "the oldest chapel in Belfast" should have been subjected to such abuse, he declared: "I can tell you I walked out of the chapel in a state of shock, not knowing if I even said the couple of prayers I usually say on a visit to a chapel." It is doubtful whether Bishop Daly's blank verse would have consoled this person.

Now that the work has been completed we can surely attempt an appraisal of it. Whether the Protestant style pulpit was restored due to protests or to fear of damaging the diocese's carefully nurtured ecumenical image we shall probably never know. Pulpits are none too popular with either Catholic or Protestant Modernists. The tabernacle's being given greater prominence is due, quite simply, to the fact that, in St. Mary's, Christ has been separated from the sacrificial altar. The Marian altar, meanwhile, has been replaced by a tiny picture set against a plain wooden panel. So much then for Fr. Patton's reassurances concerning the pulpit, the tabernacle and the side altars. And it was not even thought necessary to explain the removal of the altar rails.

What then of the high altar?

When Fr. Patton claimed that the high altar would merely be brought forward slightly, he was either badly misinformed, deliberately equivocating, or deliberately lying. The high altar has disappeared! After remaining partially covered for some time behind a newly-erected wooden table the altar was quietly removed, where to, or if it is still intact God only knows. A workman at the scene of the crime could not or would not tell me what had happened to it. So surreptitiously was its expulsion accomplished that a frequent attender at St. Mary's told me that he had not noticed the altar's disappearance. There was no need here for the armed police employed by the Bishop of Kansas City, John L. Sullivan, whose belligerent methods of altar removing recall the feats of his more famous bare fist boxing namesake. In Down and Connor we have mailed fists in velvet gloves. Bishop Daly, like all true Modernists, proceeds by means of stealth, cunning and subtlety rather than engaging in outfight confrontation.

Although the deceitful ejection of the altar from St. Mary's was certainly a Philistian act, its spiritual consequences are much more grave. St. Opatius, Bishop of Milevis (4th century), exclaimed: "What is so sacrilegious, as to break down, to erase, to remove God's altars upon which you yourselves have been sacrificed? What is the altar but the seat of the Body and Blood of Christ?"15 This applies equally to today's altar wreckers all over what is left of the Catholic world, including, of course, those responsible for destroying St. Mary's.

Although it certainly proved itself to be by far the most significant catalyst, today's attack on our churches did not start with Vatican II. As far back as 1947 Pope Pius XII was aware of attempts being made to replace sacrificial altars with meal-oriented tables. Mediator Dei (para. 66) warns that it would be wrong "to want the altar restored to its ancient form of a table." Ten years earlier, indeed, the Bishop of Linz (Austria), Mgr. Gfoellner, had rebuked "extreme liturgists" who "wished to turn the altar around and celebrate Mass facing the congregation, to remove the tabernacle, from the altar and to reserve the Blessed Sacrament in a safe in the wall, to have the faithful receive Holy Communion standing, and to forbid the recitation of the Rosary during Mass."16 Clearly the liturgical revolutionists were already practicing what they preached in 1937.

Another aspect of the "archaelogism" condemned by Pius XII is replacing durable and permanent marble altars with flimsy and transient wooden tables. Although the early Christians certainly used wooden tables as altars the practice of using stone had become virtually universal in the Latin Church by the ninth century. During the difficult penal days in Ireland it was Mass rocks rather than wooden tables which were used for Mass. The wooden table used in Belfast and still preserved (we hope!) in St. Mary's was something of an exception and was only used for want of a proper stone altar. This is indeed the case today, in Belfast as elsewhere, when Tridentine Masses have to be offered in private homes and public halls. The expulsion of the unequivocally Catholic Mass from our churches has, for the most part, preceded that of altars.

Certainly Belfast's traditionally-minded Catholics had no cause to celebrate St. Mary's Bicentenary. After two centuries, during which its Catholic identity shone forth ever more clearly, this former symbol of victory over anti-Catholic penal laws, now denuded of its unequivocally sacrificial altar, has become little better than a Protestant church or meeting house; this time in reality and not, as was true of the original building, merely in appearance. It would now be more fitting to have this whited sepulchre draped in black to mourn the de-sacrilization which it has undergone.

In fact, George Orwell's 1984 defines "doublethink" as "the ability to believe that black is white, and more, to know that black is white and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary." It is surely ironically fitting that this year, 1984, should see the effective destruction of a church followed by a celebration of its bicentenary. Doublethink makes men laugh when they should weep and rejoice when they should be sorrowful. It was very much in evidence at the liturgical happening which was concocted on 30 May 1984 to "celebrate" the 200th Anniversary of Fr. O'Donnell's first offering of the immemorial Latin Mass in "Old St. Mary's."

There were five separate events to celebrate the bicentenary, all predictably ecumenical in tone. Doublethink was certainly in evidence at the first, on May 13th. The current Anglican vicar of nearby St. George's, preaching from the pulpit donated by a predecessor, declared that, notwithstanding ecumenical cooperation, ". . . we cannot escape our past, or rather, we have to learn to face it together." In reply Bishop Daly castigated ". . . a refusal to face the past and face a new future." This was surely doublethink, if not downright hypocrisy, when he had himself physically erased the past from St. Mary's. In practice facing anywhere is now preferable to facing Our Lord in the tabernacle on a truly sacrificial altar.

A subsequent "Marian" event was little better. Although the text used by the bishop on this occasion was based on those used by the Pope at Fatima and on March 25, the parish and diocese were merely dedicated (not consecrated) to Our Lady.17 There was no rosary, merely prayers for an end to bigotry and injustice. After this event I sold quite a few copies of May's Catholic Crusader which, interestingly enough, dealt with the avoidance by so many bishops of the word "consecration" on March 25th.

The "dedication" was followed by the main event, a bicentenary Mass on May 27th. This time our bishop (selectively) "faced the past" and called for a return to ". . . the spirit of ecumenism and good will of two hundred years ago" and again tried to convince us, and perhaps himself, that "It is still Old St. Mary's!" He had previously cited Dr. Rogers' favorable verdict on the 1941 renovations as being applicable to the 1984 vandalization, but conveniently omitted the reference to the preservation of the altars and the communion rails.18The Irish News of May 28th, which reported this Mass, published a letter in which I quoted Rogers in full and passed my negative verdict on the destruction of the interior of St. Mary's. The Irish News photographs showed that the penal-era wooden altar has been dragged out to fill the space vacated by the ejected Sacred Heart side altar. This curious gesture must also have been a product of doublethink or at least of a distorted sense of history. This particular wooden altar was a symbol of the fight to have proper churches with permanent altars restored.

On the same day The Irish News reminded us that Irish altar-wrecking is not confined to Belfast. In Naas, Co. Kildare, a church was about to lose its high altar and have its side altars replaced (symbolically perhaps!) by fire exits. An objector had written:

Too many altars have been bashed up, too many old churches have become empty and meaningless . . . By what right do we, with out independence and our affluence condemn this triumphalism? Each age has its own vision of paradise: ours is skylighting, bare white walls, pile carpeting and central heating. Is it any better?

The Naas objectors have managed to preserve the stained glass windows. Indeed I have discovered that St. Mary's would have suffered even more had it not been for protests. Also, I have learned that spirited opposition to Bishop Daly's altar-wrecking in his previous diocese resulted in the retention of a side altar. Protests against vandalization of churches are obviously not entirely ineffective. However, our bishop is apparently now making up for lost time by letting an "artistic commission" loose on Belfast's "unrenewed" churches.

But enough of these gloomy thoughts: let us return to the revelry. It did not end with the bicentenary Mass. However, a pre-emptive strike had already been launched against the final event from an unexpected quarter. Father Desmond Wilson is no traditionalist. He prefers unfashionable polo necks to Roman collars and is generally regarded as something of a maverick and an iconoclast. Yet his views are often sounder than those of his more "obedient" colleagues. This turbulent priest informed us that the Reverend John Barkley, a Presbyterian clergyman and college lecturer, would be preaching in St. Mary's on May 29th. Then, following a rhetorical question as to what else Professor Barkley might be, Fr. Wilson revealed: "He is a prominent Freemason." Ironically, Barkely's sermon had been organized by a member of the Knights of Columbanus, an organization founded in Belfast to combat the influence of Freemasonry in the city and subsequently in other countries. Father Wilson continued in a typically ironical vein:

This magnificent gesture . . . is all the more praiseworthy and remarkable in view of the fact that the Pope has warned Catholics against Freemasonry . . . This can only bring great good, because we can now expect that the tolerance and friendship extended to the Freemasons may now in time be extended to all sections of the community. Including Catholics.19

Including traditionalists? It would seem not! I have again challenged my bishop concerning the legal position of the Tridentine Mass and, although this time he replied directly and at some length, he remained negative and evasive. A further letter has been sent insisting, in particular, that he should take note of Count Capponi's arguments. I await his next letter with interest but without optimism.

His latest letter began with an apology for the delay in replying due to "the pressure of life and work . . . in a diocese such as this." His Lordship was not too busy to order, within months of his arrival here, the vandalization of St. Mary's.

NOTES

1. Davies, M. Pope Paul's New Mass, p. 157.

2. Hughes, P. Theology of the English Reformers, p.221.

3. These open-air Masses were often said beneath the shelter of trees. According to Dr. Eamon Phoenix (Ulster Tatler, May, 1984) the "trysting thorn" still stands in the recently cleared Briars Bush Graveyard at Stranmillis.

4. In parts of Ireland Catholic churches are still known as "chapels." This dates from the period when only Protestants worshipped in proper churches.

5. Rogers, P. The Story of Old St. Mary's, Harpers, Belfast, 1956, p. 18.

6. Bell towers on Catholic churches were still prohibited.

7. Asquith's Chief Secretary for Ireland. He resigned following the 1916 rising.

8. Rogers, op cit. (foreword)

9. In fact it was presented by the Church of Ireland (Anglican) Vicar of nearby St. George's in return for Fr. O'Donnell's performing a successful exorcism.

10. Ibid, p. 23.

11. Daly, C. B., Mass and the World of Work, Irish Messenger Publications, 1981, p. 2.

12. Daly, C. B. "Communion in the Hand," I.M.P., 1984, pp. 4-5.

13. A nineteenth-century Scottish Protestant clergyman known as "the world's best bad poet."

14. The International Commission for English in the Liturgy.

15. Rock, D. Hierurgia; of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, John Hodges, London, 1892, p. 296.

16. Montague, G. Problems in the Liturgy, Browne & Nolan, Dublin, 1958, pp. 317-8.

17. The Bishop has since been reported as having consecrated the diocese to Our Lady.

18. Rogers, P. & Macualay, A. Old St. Mary's: Chapel Lane, Belfast, 1784-1984, p. 6.

19. Wilson, D. "Let us Know Where You Stand," Andersontown News, 26 May 1984.