The Angelus: Some History and Meditations

by Mary E. Gentges

|

Warm noonday light filled the classroom and spilled across our bent heads. Our eyes were on the bookkeeping exercises, but our minds were on lunch. Aromas from the cafeteria wafted up the stairwell, and we were impatient to be off. At the long-awaited sound of the buzzer we slammed books into desks, and sprang to our feet.

The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary, intoned Sister Louis.

And she conceived by the Holy Ghost, we replied.

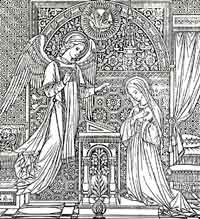

In the words of the beloved prayer, we spanned the centuries to that first Angelus almost two thousand years ago when the Angel Gabriel stood before a stainless Virgin at a little place called Nazareth in the hills of Galilee, a place the world at large had never heard of, but because of that moment the world would never forget. And because of the Virgin's answer all generations would call her blessed. At that moment the Messiah, God Himself, was conceived Incarnate in her, so that this momentous pause in time would be revered through all generations.

Across the street the church bells began to peal, as Angelus bells have for centuries. Nearly twenty years later their joyous ringing still echoes in my memory, if one happened to be in the bell tower on the stairs to the choir loft, one could feel and hear the awesome shuddering and scraping as the big bells swung in their supports.

Awesome too were the Angel's words of greeting to the Virgin:

Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee, blessed art thou among women.

On hearing that she should bring forth a Son who would be great, and of whose kingdom there would be no end, the humble maiden was troubled, and her own words give witness to her virginity. But the Angel explained that the Holy Ghost would come upon her, and the power of the Most High overshadow her, and the Holy to be born of her would be called the Son of God, for nothing is impossible with God.

Behold the handmaid of the Lord.

Be it done unto me according to thy word.

In Limbo, that place of waiting for all the just of the Old Testament, must not the First Parents, and all the Patriarchs and Prophets—Adam and Eve, Abel, Abraham, Isaac and Moses—must not they have waited in awed silence to hear the Virgin's answer, as even the angels listened, knowing that God's plan waited on her freely-given "yes." And hearing her fiat must not they have rejoiced with the greatest rejoicing since the creation of the world, knowing that their redemption was at hand? She accepted at the moment God had chosen, cooperated with the way He had ordained to bring the Messiah into the world. God's promise to Adam was fulfilled; the gates of heaven would be re-opened to mankind by Christ the Redeemer to be born of this humble Virgin.

Hail Mary . . . we repeated as the church bells joyously celebrated the Incarnation.

Catholics are sometimes criticized for repeating the Hail Mary so often, but it rings down the centuries like a bell, announcing the dawn of our redemption. Does the bell-ringer let the clapper hit the side of a finely-toned bell only once? No, he rings it again and again, just as we recall the beginning of our salvation again and again, through the bell of the Hail Mary.

And the Word was made flesh. We genuflected quickly.

God, the Word, our Creator, took on our nature. He could have redeemed us in any way He chose, but He chose to become one of us, sharing our lot in everything but sin.

And dwelt among us.

Not only did He become man, but lived—not in a remote palace—but in the midst of His own creatures. He subjected Himself to the inconveniences of being born in a stable, of having no place to lay His head, of living among men. He put up with their faults and failings, their blindness to His message, their denial of His infinite love. And finally He allowed them to crucify Him.

O Almighty God, we adore Thee who became flesh and dwelt among us, even to this very day in the Holy Eucharist!

In the Virgin Mary He found His first monstrance as she hurried across the hills to greet her kinswoman, Elizabeth. She did bear in her womb the Creator who made her, "the very One whom the heavens cannot contain" (St. Louis de Montfort).

"O full of grace, every creature, both angelical and human, rejoices in thee, for thou art the holy temple of the Lord, the mystical paradise and the glory of virgins. Through thee the Son of God became Man, although He was God from all eternity. He made thy womb into a throne, greater than the heavens themselves" (from the Eastern Rite liturgy).

Hail Mary . . .

Pray for us, O Holy Mother of God,

That we may be made worthy of the promises of Christ.

Holy Virgin, honored by God above all the women on earth, the honor we give thee is but a poor mirror of that which He gave thee. Help us to be worthy of the great promise of the Annunciation.

Let us pray. Pour forth, we beseech Thee, O Lord, Thy grace into our hearts, that we to whom the Incarnation of Christ, Thy Son, was made known by the message of an angel, may by His passion and cross be brought to the glory of His resurrection, through the same Christ Our Lord. Amen.

At the last "amen" we hurried down to lunch. Young as we were, I doubt that we gave a great deal of thought to the sublime meaning of the familiar words we said daily. Nor did it occur to us that in reciting the Angelus we were united to a practice of Catholics back to medieval times, united with the peasants Millet immortalized in 1859, in his most famous painting, "The Angelus." At the sound of the bell from the church across the field, they have paused in their potato-digging, and he with hat in hand, she with kerchief on her head, have bowed their heads in prayer, recalling the Incarnation of Christ Our Lord as had generations before them.

The Angelus as we know it today had its beginnings sometime during the Middle Ages, but cannot be pinpointed exactly. The evening Angelus came first, according to The Catholic Encyclopedia (1907). It explains that the practice of saying three Hail Marys near sunset was certainly general throughout Europe in the first half of the fourteenth century. It may go back far earlier, but there are written indications of it at least a century before, such as the Ave Maria inscription on bells that have survived to recent times, suggesting that they were originally intended to serve as Ave bells. One German bell dated 1234, bore the entire sentence, Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum.

Many English bells were dedicated to St. Gabriel and were inscribed with such Latin phrases as "I bear the name of Gabriel sent from Heaven," or "The messenger Gabriel bears joyous tidings to holy Mary."

To greet Our Lady at sundown was appropriate, for it was traditionally believed that the Annunciation took place in the evening, and the Prince of Peace then dwelt among us. A popular inscription on German bells as early as the thirteenth century runs: "O King of Glory, Come with Peace." In Germany, the Netherlands, and parts of France, the ringing of the Angelus was popularly called, "to toll for peace," and the bell was regularly known as the "peace bell," a designation later given in various places to the morning and noontide Angelus.

From the beginning the triple stroke repeated three times seems to have been the custom, with a pause between each group of three to allow the recitation of an Ave, or a Pater, and an Ave. One fifteenth-century bell bore the words in Latin, "When I ring thrice, thrice devoutly greet the Mother of Christ."

For the lay people, many of whom could not read, the Hail Mary took the place of the elaborate prayers of the monks, and they were encouraged to say it when the bell rang for the monks to say their evening prayers.

Bear in mind that in medieval times the Hail Mary consisted only of the Biblical salutations of the Angel and of St. Elizabeth, and was essentially a greeting to the most holy Virgin. At the beginning of the thirteenth century bishops began exhorting their clergy to see that the "Salutation of the Blessed Virgin" was familiarly known to their flocks, as well as the Creed and the Lord's Prayer.

Gradually the word "Jesus" was added to conclude the greeting. And then in their private devotions the faithful began adding a petition, tending to be an appeal for sinners and especially at the hour of death. In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries we meet the Ave printed much as we know it today. The Council of Trent (1545-63) fixed permanently the last half of the Hail Mary in its present form, stating in its Catechism that this second part was framed by the Church itself.

Meanwhile, shortly after the evening Angelus became familiar, a custom established itself of ringing a bell in the morning and saying the Ave thrice, perhaps in imitation of the monastic triple peal rung at Prime. The earliest mention of the morning Angelus seems to be in the city of Parma, where in 1318 the bishop exhorted all who heard it to say three Our Fathers and three Hail Marys for the preservation of peace.

The midday ringing was last to develop and was closely associated with veneration of the Passion of Our Lord. At first it was run only on Fridays, as at Prague in 1386, and Mainz in 1423.

A bequest to the churchwardens in Cropredy, Oxfordshire, in 1512, mentions the thrice-daily Angelus. It was made on the condition they "toll dayly the Avees bell at six of the clok in the mornyng, at xii of the clok at noone and at foure of the clok afternoone."

Instructions in late sixteenth-century devotional books suggest that the Resurrection be honored at the morning ringing, the Passion at noon, and the Incarnation in the evening, corresponding to the hours when these great mysteries occurred. The Regina Coeli (which we presently substitute for the Angelus during Paschal time) was suggested for the morning, Passion prayers at noon, and our present Angelus versicles for sundown.

The complete form of the Angelus now universally adopted can be traced definitely to the year 1612.

In the modern world the practice of recalling these sacred mysteries is all but gone. Perhaps there are no bells, not even a noonday or evening whistle in your community to remind you to say the Angelus. Still you can form the habit of reciting it fairly close to the traditional hours. Say it while getting ready to go to work or school, while preparing breakfast, or on the way to work. Again, you can say it before eating lunch, and at evening on the way home.

Some families say the Angelus before meals along with grace, a worthy practice. Surely each of us can manage to pray it at least once—if not the ideal three times—a day and thereby celebrate daily that inexpressible moment of the Incarnation when God became Man and dwelt among us.

Angelus Domini nuntiavit Mariae . . .