Book Review: The Liturgical Revolution

It is commonplace today to recite the remark of Pope Paul VI that the smoke of Satan has entered the Church. And indeed the events of the past fifteen years are so baffling and so unaccountable that ordinary historical explanations of what has transpired leave us still unsatisfied, and we grope for illumination toward the mysteries of the spirit—the mystery of providence, the mystery of grace, the mystery of iniquity.

But before anyone attempts such an accounting, he has got to get the material facts straight, and this is just what Michael Davies does in this monumental trilogy. We have all had our personal experiences of the Liturgical Revolution and have shared piecemeal in the adventures of others. What Davies has done is to identify hundreds of such experiences, document them with precision, systematize them in an orderly way, trace them back to their original source in some official document or theological proposition, explain the issue of Catholic faith involved, and identify the major trends and personalities in the continuing struggle for and against a liturgy worthy of the faith.

When these volumes and Davies' other books are finally recognized outside the narrow circle of traditionalists (and there is evidence that recognition may come soon), it is rather easy to predict that adversaries will ignore the substance of his work and concentrate on his style and method. Before the charges come, it may be well to take a close look at how he goes about his task. First, his writing is marked by a scrupulous attention to factual detail. In reporting the doings of some cleric, for example, Davies is never content to attribute to him just an attitude or disposition, but he customarily identifies the man carefully, notes the titles or offices he holds, quotes the man's very words where possible, sketches the circumstances in which they were said or written, and provides references to the sources of information. If there are moments of tedium in Davies' writing, they are due to this meticulous attention to factual detail.

Secondly, in assessing the significance or implications of such facts, Davies ordinarily offers us the judgments of third parties who may be for, or against, or neutral about the issue. For example, in judging that such and such a phrase in the Novus Ordo has Protestant tendencies, Davies will produce a progressive liturgist who defends the phrase for not giving offense to Protestants, then a Protestant theologian who is gratified by the phrase as a concession from Rome, then perhaps an impartial or traditionalist authority who deplores but confirms the phrase's tendency. This objectivity is a cause of some repetition, especially when the authority's judgment is pertinent to the several issues of several chapters, but it provides the convenience of making every chapter nearly self-sufficient.

For all this corroborating testimony, Davies makes no bones about his own judgment on the matter at hand. He is not in the business of simply recording facts and a variety of opinions about them; he wants us to understand what they mean—for example, how irregular certain proceedings were, how devious the people involved, how deliberately ambiguous a statement is, how inimical to the Church, and how it is all of a piece with some larger idea like ostpolitik or ecumenism or the Cult of Man (a phrase he gets, if I am not mistaken, from the Abbé de Nantes). And in this element of his writing Davies employs that venerable technique which Catholic apologists have found so congenial, satire. (One thinks of recent writers like Belloc, Chesterton, and Waugh; but I also remember an old translation of Augustine's City of God in which one of the first chapters of Book III was something like, "A Vituperation Against Those Who Rejected Books I and II.") His satire is not extensive but is supple; sometimes he has a light-hearted spoof of a bit of foolishness, sometimes a grim sneer for a graver skulduggery, and occasionally some Augustinian vituperation. Even in its satire, Davies' writing never approaches anything like extravagance or slander.

Another feature of Davies' method is his citation of 'approved authors' in theology and history. Some pedant will surely quibble about this, for it is true and some of his authors from a previous generation (like Dom David Knowles and Father Philip Hughes) are nowadays somewhat dated. On the other hand, it would be altogether inappropriate in a popular, apologetic work like The Liturgical Revolution to attempt a careful assessment of current scholarship in these academic disciplines. I have noticed no instance, by the way, where his reliance on such authors has placed his argument in jeopardy.

It is hardly possible to offer any kind of meaningful summary of the contents of these three volumes in the space of a review, but perhaps a few reflections on each volume will do some kind of justice to them.

|

Volume I |

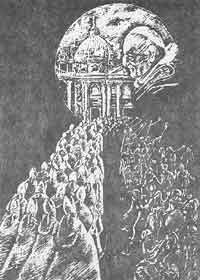

CRANMER'S GODLY ORDER is an historical account of the 'renewal' of the Mass and the Church in England effected by Henry VIII 's Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. He designed a liturgy, the Book of Common Prayer, which substituted various Protestant opinions for such Catholic truths as transubstantiation, the Real Presence, sacrifice, oblation, propitiation, the priesthood and related doctrines. Cranmer did many other things as well: he required oaths of loyalty, weeded out unsympathetic clergy, persecuted devout traditionalists, prescribed heretical sermons to be read in the churches, proscribed Catholic devotions, promoted heretical publications and suppressed Catholic ones, and so on, and so on. But nothing he did was so successful in destroying the faith of English Catholics as his liturgical innovations. Nothing could strike so near a Catholic's Catholicism as a blow against the Mass—whether he were a learned theologian with an intellectual grasp of how all revelation converged and blossomed in the Mass, or whether he were a simple fellow who knew only, but with equal certainty, that his attendance at Mass, beads in hand, was his presence at Calvary. For every sort of Catholic, to take the sacrifice out of the Mass, as Cranmer did, was to remove the keystone from the whole symmetrical arch of faith. And the faith did indeed collapse, except for a distressingly small remnant—specifically, for those who refused Cranmer's new service.

Catholics have long understood just what Cranmer's Book of Common Prayer did to the Mass, and have deplored it; Protestants have agreed, and praised it. All this was a simple historical fact about the Catholic Church, an objective historical datum. But with Vatican II a new breed of liturgist has come along, and he acts on the premise that Cranmer was right after all, that he was closer to the Apostolic faith than the Council of Trent was when it confirmed the immemorial Catholic Mass.

Historical events like Cranmer's corruption of the Mass are an important part of Catholic belief—not to be ranked with Scripture or dogma or morals, of course, but a part of Catholic belief nevertheless. Events like the early Christians being thrown to the lions, the cancers of Arianism and Albigensianism, the outbursts of iconoclasm, the crusades to rescue the Holy Land, the flowerings of theology or mysticism at various times, the sanctity or the corruption of prelates, the heroism of saints, the sacrifice of missionaries—these and a thousand other events are the story of the age of the Holy Ghost, following the example of the Acts of the Apostles, and they define with wonderful detail and glorious perspective what the Church is and how the Church Militant fares.

And so Davies tells again this Catholic truth about the sixteenth century. And in doing so his constant theme is indisputably the right one: that the lex orandi is the lex credendi, that what men pray is what they believe. And Davies does not hesitate to point out the chilling parallels between what happened to the Mass and the faith in the sixteenth century and what is happening today.

|

Volume II |

POPE JOHN'S COUNCIL. Ambiguity. This is the large, the sickening character of Vatican II and of the 'spirit of the Council' which it spawned. If there are gems of spiritual wisdom in the work and the results of the Council, they remain buried in a junkyard of deceit, hypocrisy, guile, cunning, and fraud. Ambiguity is that form of intellectual dishonesty in which some lesser element of a truth is asserted in such a way as to damage the central truth. It has a thousand faces: that of the pragmatic man who simply denies the theoretical foundation of what he does, refusing to admit the implications and consequences of his deeds; that of the political ideologue, who is willing to sacrifice justice and truth to his visionary Utopia; that of the sentimentalist, who claims that an attitude of niceness is sufficient justification for any sort of folly; the ambiguity of the bureaucrat, who acts as if the world were created to increase his staff and his budget. While many of us may be guilty of these kinds of knavery from time to time, the 'spirit of the Council' raised ambiguity to a method of government, a goal to be achieved, and a fine art.

As a method of government, ambiguity is at the heart of all those directives and exhortations which distort things Catholic, and yet insist that the change is no change. In the formulation of schemata at the Council this took the form of inserting an ambiguous word or phrase in a Catholic text, hustling it through the process of the Fathers' approval, then afterwards extracting the phrase and implementing it in its most un-Catholic sense. These are what Davies calls the "time-bombs" of the Council. Ambiguity is also the managerial method of dealing with Archbishop Lefebvre and other obstreperous clergy—the imposition of sanctions based on a drummed-up bit of trivia while denying the real reason for punishment.

As a goal to be achieved, ambiguity is practically synonymous with the meaning now attached to ecumenism. The whole gist of ecumenism is to avoid mentioning those things about the Catholic Church which various heathens and heretics find objectionable and to concentrate instead on those things which all men agree on—which is precious little. The convinced Catholic who sets out on this path must suppress his most cherished beliefs and somehow generate zeal about things which, without them, have very little meaning. Thus he must quit talking about salvation and worry instead about employment; he must abandon devotion to the saints and get involved in the labor or women's movements; instead of examining his conscience he examines financial statements; he no longer contemplates the last four things but the bottom line; instead of baptizing people he registers them to vote—because incomes, unions, budgets, bottom lines, and ballots are what the modern world agrees are important.

As a fine art, ambiguity is seen among the new breed of canonists, Biblical scholars, catechists, theologians, and organization men, who appeared at the Council and have flourished ever since. Your Biblical scholar, for example, has discovered several formulae which give him a kind of legalistic immunity while he diminishes the faith. "I can find no scientific evidence for the virgin birth," he says, for example. All he says, of course, is that we have no notarized statement from an attending physician at the Nativity—as if our faith rested on such things—but what he means is that we should no longer believe in the virginity of Mary and in the Gospels which report it. And this is just what his audiences understand, and do. Or your activist priest says he does not subscribe to communism but finds Marx a useful critic of the ills of society—but what he means is that he going to be a nice communist, not like those crude Russians.

Davies does a much better job that I am doing in sticking to the issue of the Liturgical Revolution. He does not try to give a general assessment of the Council and its bitter fruit, and so he touches only incidentally on such matters as the impact of the Council on seminaries, the religious orders, vocations, the Catholic press, Catholic schools, preaching, missions, catechisms, Church government, and the like.

|

Volume III |

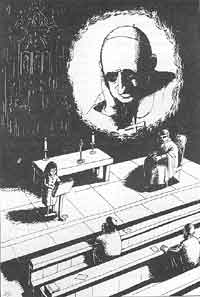

POPE PAUL'S NEW MASS. Those who pick up this volume should recite a prayer for patience and prudence before reading it. It is infuriating—not the book itself, of course, but the butchery of the Mass which it records and explains. And of the first observations to make about it is to admire the restraint which Davies exercises in telling the sordid tale. For he does not call the butchers butchers but painstakingly documents the havoc they have wrought. And he does not conclude (as many have) that the New Mass is a non-Mass, as Cranmer's is (or that the Pope and most bishops are no longer in the Church, as some have concluded), but only that it is a mangled Mass—speaking of the rite itself and not of any particular performance of it—a mutilated Mass that promotes misunderstanding of the faith and lends itself to sacrilege. No doubt it is a proof of the Petrine promise that the Holy Sacrifice should be able to survive the savagery of resolute scoundrels resisted mainly by feckless and tepid defenders of the faith.

Last spring Pope John Paul II deplored abuses in the liturgy. We might take comfort from such a development if it were not apparent that the Pope is unprepared to admit what Davies helps us to see with crystal clarity: it is not so much departures from the New Mass that are the scandal as it is the New Mass itself. No one can be terribly shocked that men occasionally break a law: infinitely more harm is caused when the law itself is bad. The New Mass, as given us by him who held the keys of the Kingdom and as 'improved' by the mad-dog liturgists he set upon us, with its incessant volubility, its superficial chumminess, its mob psychology, its timeliness and un-timelessness, its ambiguous language, its official mistranslation, its often inane petitions, its unpenetential quality, its shallow cheeriness, its table instead of altar, its misplaced tabernacle, its superfluous relics, its bashed-down altar rail, its burlap vestments, its irreverence, its materialism, its secularism, its rationalism, its man-centeredness, its Calvinist work ethic, its president, its unpriestliness, its idiosyncrasy-producing options, its freewheeling way with the sacred species, its recreation hall architecture, its pots-and-pans sacred vessels, its Bisquick hosts, its repudiation of musical treasures, its Protestantism, its casualness—it is these abuses, these officially required or encouraged abuses, our dear Father Wojtyla, these commanded misrepresentations of Catholic Truth and misdirections of Catholic piety, which are pell mell dividing men from each other and from Jesus Christ.

Even the historical precedent provided in Cranmer's Godly Order and the chicanery of the new reformers described in Pope John's Council hardly prepares us for the spectacle of fools and knaves rivaling one another in liturgical tomfoolery—and this not only among the crazies in the provinces but also in sober pronouncements from the highest authorities.

The more information Davies provides, the more the catastrophe increases, in a way, our stupefaction. This is because we are dealing with a phenomenon which can be described, but not fully accounted for, by the ordinary laws of language, history, authority, aesthetics, psychology, morals, and the like. The great service Davies performs here and in his other works, is to put us in a position to begin approaching those spiritual mysteries which are the ultimate explanations of these latter days—the mystery of providence, the mystery of grace, the mystery of iniquity. *

Malcolm Brennan is Professor of English the The Citadel in Charlestown, South Carolina. He has been a regular contributor to these pages since the inception of The Angelus. God willing, his series, "Martyrs of the English Reformation" will appear in book form in 1981.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Mr. Davies' Volume III of The Liturgical Revolution, Pope Paul's New Mass, will be published by the Angelus Press later this month. Please see the inside front cover for our special pre-publication offer for subscribers which will be valid UNTIL SEPTEMBER 25, 1980 ONLY.

The first two volumes of this trilogy, Cranmer's Godly Order and Pope John's Council, are currently out of print. They are, however, being reprinted by the Angelus Press and should be available in late October. Please watch for an announcement regarding our special offer to subscribers. We also plan to produce some of the chapters of Pope Paul's New Mass as pamphlets. We would greatly appreciate it if our readers would inform us of particular chapters they would like to distribute in pamphlet form.

As with other volumes in the past, the Angelus Press will be most pleased to assist in distribution of Pope Paul's New Mass. If you wish to present a copy to your parish priest, or to a member of your family, or a friend, simply send us the cost of the book, the name and address of the recipient and we will send the book out for you.