A GRAIN OF WHEAT IN THE DESERT

Orphan, prodigal, spendthrift, agnostic, soldier, debauchee, map maker, explorer, writer, Trappist monk, hermit, inspiration for religious communities, victim of an assassin's bullet. All apply to one life–that of Charles de Foucauld, scheduled to be beatified by Pope Benedict XVI on November 15, 2005. The life of Père de Foucauld–or Brother Charles, or Charles of Jesus, as he is variously known–manifests the hand of grace following a prodigal soul, patiently waiting for that soul to turn around, enveloping it, then guiding that soul to God by the love infused into it.

Travails

His early life made him an unlikely candidate for beatification. Born Viscount Charles Eugene de Foucauld on September 15, 1858, in Strasbourg, he had an illustrious Catholic lineage: his ancestors were crusaders, friends of royalty, and proxies of kings. By the time Charles was born, his lineage had fallen on hard times. His father Edouard liked to drink and overeat, and succumbed to a depression so severe he began raving, unable to recognize his family.

Edouard Foucauld's degeneration caused his own father (Charles's grandfather) to die of grief. Then Charles's mother died during a miscarriage at age 34. Edouard died several months later. Then Edouard's mother, entrusted with the care of Charles and his sister Mimi, died of a heart attack. Charles was six.

His maternal grandfather, Colonel Morlet, became the guardian of Charles and Mimi. Then the Prussians crushed the French army and took over the country, claiming Strasbourg as their own. Bereft of his family and his homeland, Charles's single passion was to kill Prussians, something he was in no position to do. Overweight, hypersensitive, and given to outbursts of rage, he was a devastated young man who was now pampered by his maternal grandparents, no doubt out of pity for his plight.

Charles's grandfather enrolled him in a Jesuit boarding school in Paris. There were many rules and much rigor, too much for Charles, who rebelled and declared himself a "free-thinker." His disgust with theology and the Mass turned into boredom. He was never an atheist, but for years he was a determined agnostic.

He was also mismatched at Saint-Cyr Military Academy, a barracks school even more rigorous than the Jesuits. Charles's passion for killing Prussians could not sustain him through the physical requirements of military training. He was chubby and slothful, in poor contrast to his fellow would-be officers. Yet his grades put him near the top of his class.

Then in 1878 Colonel Morlet died, leaving Charles a large inheritance. Around the same time he received a large delayed inheritance from his parents' estate. He was 20.

Charles immediately indulged himself in all the pleasures of the flesh. His second year at Saint-Cyr was a disaster; he finished near the bottom of his class. He spent most of his time eating imported delicacies, smoking imported Havana cigars, drinking champagne, and entertaining young ladies and other "friends." He became known to his classmate as "Fat Foucauld," or simply "Le Porc (the Pig). "I'm doing what my father did," Charles said. "I'm eating."

He managed to graduate from Saint Cyr (last in his class), and was assigned as a cavalry officer. He continued his life of debauchery and was eventually placed under house arrest and put on inactive status.

He languished in his decadence, "with the vague disquiet that comes from a bad conscience that, although fast asleep, is not quite dead."

Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre visits the tomb of Charles de Foucauld

which was within the bounds of the Apostolic Delegation

of French-speaking Africa (1954).

Africa

When Charles heard that his regiment was headed for Algeria to put down a jihad, he unaccountably straightened up and was allowed to join his regiment in Tunisia. To the surprise of all, Charles not only withstood the sweltering heat and poor conditions, he proved himself a leader. His commanding officer wrote of him:

Cheerfully putting up with the harshest trials, constantly risking his life, scrupulously looking after his men, he won the admiration of the regiment's experts....

But when the battle campaigns were over, Charles found ordinary camp life unbearable. He resigned from the army and, resolving to explore Morocco, began learning Arabic and Hebrew. His family appointed a legal conservator over his finances and threatened to cut off his funding. Charles went ahead with his plans. He hired as a guide a former rabbi with a thirst for gold that turned him toward alchemy. Charles disguised himself as a poor rabbi and the two went into the desert.

With a sextant and notepaper, Charles began analyzing the entire country, something the French had not been able to do, as Morocco was barred to Christians. While staying at Jewish homes, Charles learned that Morocco longed for the prosperity of French-controlled Algiers. The sultan was bleeding Moroccans white with taxes and doing nothing to stop bands of murderers and robbers from victimizing farmers, the wealthy, and the innocent.

Charles discovered that the lawlessness was general.

Overwhelming greed is the rule everywhere. Lying and thieving in all forms. Banditry, armed attacks are considered honorable actions...even among the Jews, who fulfill scrupulously their duties before God and make up for it by their treatment of men....They talked to me frankly, as a brother, boasting of criminal activities, confiding to me their basest sentiments.

Even though he hired an armed guard to travel with him, he had numerous brushes with death. Had the roaming thieves and murderers known he was a French spy they would have cut his throat immediately (not that disguising himself as a Jew warded off many dangers).

Through it all, Charles doggedly mapped the country, traveling through endless plains, forests of palm trees, mountain passes with snow-capped peaks towering over his head, and vast deserts of ever changing sand dunes, dotted with mysterious, life giving oases. At night he looked up at the immense blackness, poked through by millions of stars. Sometimes he thought he was being followed and turned quickly. He could see nothing.

In the end he mapped out 1700 miles, wrote down thousands of observations, drafted 135 drawings and 20 maps. He returned to Paris a hero, and lashed everything together into a book that was eagerly received and widely praised; among the honors given him was the Gold Medal of the French Geographic Society. When things were back to normal, however, Charles was bored once more; but this time he knew it was not boredom–it was despair.

Conversion

Islam had attracted him, a consequence perhaps of the love he felt for Africa and African peoples. He still declared himself a free thinker, but his long exposure to beautiful, silent, harsh Creation seems to have started his road to conversion. He read a book (by Bossuet) his cousin, Marie de Bondy, had given him for his First Communion, and the words leapt off the page at him. Marie had introduced Charles to religion and prayed for him all these years. He concluded: "Since she possesses such an intelligent soul, the religion in which she so firmly believes cannot be the madness I think it."

He began visiting Catholic churches to pray: "God, if you exist, make yourself known to me." One of the churches was St. Augustine's. The parish priest was Marie's confessor, Fr. Henri Huvelin. Early on the morning of October 30, 1886, Charles resolved to visit Fr. Huvelin. He found him in the confessional. He told Fr. Huvelin he did not come to make a confession because he didn't have the Faith. When questioned, Charles admitted that he was born and raised a Catholic, and once believed. Fr. Huvelin told him: "What is missing now, in order for you to believe, is a pure heart. Go down on your knees, make your confession to God, and you will believe."

Charles protested, but Fr. Huvelin insisted he confess. Charles did so. A good while later he received absolution and felt its cleansing effects. "Have you eaten?" Huvelin asked him. Charles said no. "Receive Communion." It was an order. Afterwards, Charles didn't just believe, he knew: "As soon as I believed there was a God, I understood I could do nothing else but live for him, my religious vocation dates from the same moment as my faith."

The conversion of Charles de Foucauld seemed instantaneous, and his faith seemed to grow for the rest of his life. His main difficulty was finding the proper outlet for it. He wisely asked Fr. Huvelin to be his confessor and spiritual advisor, and the holy priest agreed, something he would at times regret over the years. Like many, he came to believe Charles was a saint. Like most saints, Charles's personality was left intact. This caused numerous problems, the majority of the problems afflicting Charles more than others.

He was best suited to be a hermit, but at times he longed for human contact, particularly with his family. Yet he was always moving away from them to follow God. As he explored Africa, so would he explore his new religion: basically alone, unearthing mines of spiritual treasure.

"He makes of religion his love," Fr. Huvelin told Charles's family. He was a temperamental lover in that he seemed to careen from states of profound inner mysticism to profound anguish at his lack of growth in the spiritual life. In the beginning this arose out of pride, and his waning attachment to Islam. Fr. Huvelin wisely exhorted Charles to simply live "in imitation of Christ." Another counsel made a deep impression on Charles: "Jesus has so taken the last place that no one will ever be able to wrest it from him."

Journeys

So it was that two years after his conversion Charles set off for the Holy Land, "to put myself at the foot of the cross." From Jerusalem he went to the noisy Arab city of Bethlehem, and, finally, to Nazareth. There he realized that to truly imitate Christ he would have to be obedient and obscure:

Throughout his life, he (Christ) descended: by becoming flesh, by becoming an obedient little child, by becoming poor, abandoned, exiled, persecuted, tortured, by always putting himself in the last place.

Charles returned to Paris, and with the help of Fr. Huvelin and four spiritual retreats (he couldn't make up his mind) entered the Trappist monastery of Our Lady of the Snows. He completed his novitiate in six months. The former rebel was now a model of obedience. His superior commented:

This fine young man has cast off everything. I have never seen such detachment and, along with that, overwhelming modesty. He can boast of having made me weep and feel my lowliness.

Stopping in Paris long enough to say good-bye forever to his family, and to give his worldly goods to his sister Mimi, Charles set sail for Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, an impoverished, remote priory in the Syrian wilderness, where he was known as Brother Marie Alberic. Charles felt great peace–for a time. His fasting and scourging made him ill; even his Superior noted Charles had "a somewhat excessive love of bodily mortification," and admonished him to lighten up.

His Superior also wrote a letter to Charles's former Trappist superior:

Brother Alberic is still the little saint you know...he always sets an example, often makes us joyful, and sometimes frightens us. Keep praying hard for him. His perfection is too great to be lasting.

The first hermitage a Tamanrasset (1905).

The test came when Charles discovered his Superiors wanted him to become a priest and, eventually, the Superior of their Order. He was mortified: the priesthood was too high, too exalted a vocation for him. But he obeyed–barely. Secretly he was drafting a Rule for his own Order, based on the Rule of St. Benedict, but more severe. Most likely any neophyte that came within Charles's orbit at that time would have either died or fled into the night.

In 1896 Charles was sent to Rome to study for the priesthood. His new Abbot, Dom Wyart, soon realized that Charles's present vocation was not the priesthood. It was a difficult decision to allow this promising, saintly man, to leave their Order. As for Charles, he remained silent, willing to accept Dom Wyart's decision, convinced that he would have to become a priest out of obedience. The Abbot declared:

You are free, my son. You can follow the particular vocation that seems good to you. After prayer, study, and reflection, the fathers recognize in you a special vocation outside the rule. May God guide your footsteps.

The footsteps headed towards Nazareth. Charles became a gardener and handyman for the Poor Clares. He lived in a tool shed perhaps seven feet square. He spent much of his time in the chapel before the Blessed Sacrament. He ate one meal a day, consisting of bread and water. When he slept, which was seldom, a stone was his pillow. He was ecstatic. The Abbess remarked: "He leads a life more angelic than human." Although his ideal was to be "a humble, obscure workman of Nazareth," he was spectacularly incompetent at any sort of manual labor: a Sister remarked that Charles "was incapable of planting a head of lettuce." The Abbess and all the Poor Clares began praying that Charles would reconsider the priesthood. Their prayers were heard, and Charles became determined to become a priest–a priest that is, without a parish, a monastery, or a mission: a roaming priest who could begin his own Order.

He returned to France, but was turned down for the priesthood by the Archbishop of Paris, who considered Charles a spiritual gadfly who wouldn't stay put. Charles traveled to Rome in order to discuss matters with the Pope: not just the priesthood, but the Order Charles wanted to start. The closest he came to Leo XIII, however, was a general audience. Then he was shunted off to Vatican bureaucrats, and a dead end.

He returned to Our Lady of the Snows and was happily taken back. His Superior prepared him for the priesthood. On June 10, 1901, Charles celebrated his first Mass in the presence of his sister Mimi. He was authorized to be a "free priest" and to live alone. Fr. de Foucauld immediately resolved to leave for Africa, to live in poverty and obscurity, helping the poor and converting Muslims. He intended to go to Morocco because "There are regions there where souls, deprived of the means of salvation, fall into hell in droves."

|

|

|

|

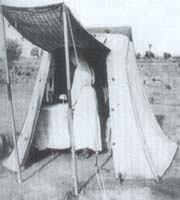

The tent-chapel where Fr. de Foucauld celebrated Mass when he was traveling in the desert. |

|

The hermitage/fort in front of which Fr. de Foucauld was killed. |

But Fr. de Foucauld was barred from entering Morocco, so he lived for a time in the Sahara desert near the Moroccan border, dreaming of setting up his own religious fraternity. Members would have to "be ready to have head cut off, be ready to die of starvation, and to obey him in spite of his worthlessness."

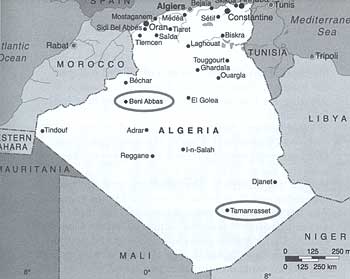

He spent the rest of his life shuttling between Beni-Abbes and Tamanrasset (in southern Algeria), redeeming slaves, feeding the hungry, teaching, evangelizing, and being absorbed in contemplation. In 1908 he visited France at the request of his family. While there, the Bishop of Viziers (the diocese Fr. de Foucauld was loosely attached to) approved statutes for his fraternity: "The Union of Brothers and Sisters of the Sacred Heart–a pious union for the evangelization of the colonies."

Fr. de Foucauld's method of evangelization was not to argue with the Muslims, whom many of the White Fathers considered impossible to convert. He lived among the poorest as an obviously devout Christian, feeding, caring, and praying for them, and letting this example speak for itself. He sought "to see Jesus in every human being; to see a soul to be saved in every soul; to see a child of the heavenly Father in every man; to be charitable, peaceful, humble and courageous...."

He called himself a "universal brother," a term that has been misused by contemporary communities claiming his spiritual legacy. They and others say that Fr. de Foucauld did not try to convert Africans, that he saw no need for it, that he simply sought to share their poverty as a fellow human being.

This is naturalism, of course. It seems that many of the religious communities allegedly inspired by Fr. de Foucauld have little knowledge of him, and of what he was trying to do in Africa, for Fr. de Foucauld made plain the intentions of his religious fraternity: they were to be

an avant-garde troop ready to work in the fields of Morocco, who, at the foot of the Sacred Host and in the name of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, will dig the first furrow in which the preaching missionaries will then be thrown as soon as possible.

"Welfare and hospitality," he said, "the example of the evangelical virtues, above all the prayers and holiness of all those who serve, and still more the great number of Masses and tabernacles, will begin the work of conversion."

He wrote from Africa to his friend, Henry de Castries:

May Jesus reign in these places where His past reign is so uncertain! As to the possibility of His reign to come, my faith is unshakable: He shed His Blood for all men. His grace is powerful enough to enlighten all men. "What is impossible with men is possible for God"; He commanded His disciples to go out to all men: "Go throughout the whole world preaching the Gospel to every creature"; and Saint Paul added: "charity hopes for all things"... I hope, therefore, with my whole heart for these Muslims, for these Arabs, for these infidels of every race....

Death

In 1914, the Great War began in Europe. As Germany sought to penetrate French borders, German arms were supplied to tribal chieftains in the French colonies in Africa, and they began an insurrection. Most of the colonial French Army had been pulled back to France, and small outposts like Tamanrasset had little or no military support. Fr. Foucauld was urged to leave, but he would not.

On December 1, 1916, he was pulled from his prayers by a band of rezzou who intended to kidnap him and ransom him for Muslim prisoners. They lashed his arms behind his back at the elbows. They beat him, forced him to his knees, and demanded he pledge allegiance to Allah. He said no word and shook not. His lips moved silently, in prayer, or repeating a meditation found in one of his notebooks:

To be as poor and small as was Jesus. Silently, secretly, obscurely, like him. Passing unknown on the earth like a traveler in the night, disarmed and silent before injustice, like him, the Divine Lamb, I shall endure being shorn and sacrificed without resisting, without speaking, and the hour come, I shall imitate him in his way of the Cross and his death.

His captors tore his clothes and threatened him with death. There was confusion and rifle fire, and Fr. de Foucauld slowly fell onto his side, a bullet through his head. They buried him in a ditch and pillaged the mission, desecrating the Blessed Sacrament, and strewing De Foucauld's writings about as they looked for treasure.

Just before Christmas a small French regiment came to Tamanrasset. One of the notebooks they recovered was entitled, "Live as if I were to die a martyr today." They put a cross over his grave, but did not disturb it. The following year the body was exhumed in order to move it to higher ground. The hands were still behind the back, the body in a kneeling position. General Laperrine wrote Charles's family: "Your brother was as if mummified, and he could still be recognized. The transfer of his remains has been a most emotional experience."

In 1927 the cause of beatification for Fr. Charles de Foucauld began. In recent years he has been hailed as a forerunner of Vatican II, and his colonial ties and zeal to convert the Muslims are not noted. De Foucauld himself thought his efforts might "take centuries" to bear fruit. He may best be likened to a grain of wheat that falls on the desert sand and dies, a death which God uses to work miracles. A friend said of him, "He died as the guest, hostage, and ransom of the Muslim." For us he has left his life and this prayer of abandonment:

Father, I abandon myself into Your hands;

do with me what You will.

Whatever You do I thank You.

I am ready for all, I accept all.

Let only Your will be done in me,

as in all Your creatures,

I ask no more than this, my Lord.

Into Your hands I commend my soul;

I offer it to You, O Lord,

with all the love of my heart,

for I love You, my God, and so need to give myself–

to surrender myself into Your hands,

without reserve and with total confidence,

for You are my Father.

Sources

Antier, Jean Jacques. Charles de Foucauld. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1999.

Brother Bruno of Jesus. "A Son of the Church: The Spirit of Father de Foucauld." The Catholic Counter-Reformation in the Twenty-First Century, February, 2005.

Catholic World News Report Online Edition, and numerous Charles de Foucauld web sites.