15 Minutes with Fr. de Chivre: PURITY

As long as we insist on classifying the problem among the sickly fears of a grotesque moralism--or moralizing--it will always explode in a vicious liberation. Rigorism inclines us to vice much more than to virtue. Laxism diminishes a man far more than it reinforces his dignity.

The sole transcendent dignity of a man arises from his spiritual life. The spiritual lie is necessarily associated with the life of the senses, either to receive a loyal expression or else to be stifled and betrayed in its manifestation.

A theory of blind, automatic, or sheer willpower will never be able to give us the complete solution. In reality, there are two aspects to the question of purity, just as with all the other virtues: First, there is an aspect that is general and obligatory for absolutely everyone: "Thou shalt not commit adultery." Then there is an aspect of purity that is individual: it is none other than the obligatory aspect as applied to our life, according to our differences of temperament and physical and moral state; according to unforeseen and necessary circumstances; according to the light received by each one of us, either blinding in its demands, or else veiled and obscure; all falling under the same general "obligatory" but applied to the individual.

What does obligatory mean?

It means indispensable to retaining the characteristic of man: an incarnate spirit. What do we mean by that expression? We mean that two contraries are bound together toward a shared action: a pure spirit, with no blending of non-spiritual elements; a flesh composed of non-spiritual elements: instincts, passions, emotions, lower desires, etc.

So how can we resolve the problem? By studying the two opposed realities each in its proper light, with an exact knowledge of each reality and of the natural and supernatural mission proper to each, a knowledge which ought then to move the will toward a decision, not based on a blind formalism but based on real circumstances in the light of one's conscience and of God's grace.

There is an unceasing obligation to purity, governed by laws which are very precise indeed, but there is no obligatory formula for purity separate from the given moment in which an individual ought to be pure; or decreed before that moment without any practical relation to that particular moment in time. Gluttony, too, falls under an obligatory command, but I should not dissociate that command from the moment in which I am going to pose an act which is materially close to gluttony but which will in fact be morally virtuous: the act of enjoying taking that extra apple out of the basket, freely and voluntarily, but for an overriding motive of good health and as directed by the mind.

So what is it to know? In French, connaitre, like the Latin, nascere cum, to be born with: Deciding in favor of an act of the senses because a legitimate spiritual reason is born with the sensible desire, giving the act a reasonable and virtuous direction.

For what regards purity, this knowledge can take three forms: prudishness, the sense of decency or shame, and purity.

Prudishness

Prudishness can be described as the anxiety to preserve the spirit to the point of wanting to see it dis-incarnated: of wanting it to act without opening its eyes, without feeling any emotion, without participating in the physical and physiological reality of the body. It is a sort of absurd constraint betraying a formal ignorance of the real, since an incarnate spirit is specifically designed to collaborate with the reality of the flesh. Prudishness can even reduce personal grooming to the anti-virtuous absurdity of the "strict necessary" at the expense of cleanliness and general hygiene.

In this domain, then, what should be the participation of the spirit? How do we act in a way worthy of the soul? By granting to the real, fully and honestly, what is physically due to it, without abasing the soul by an excessive participation in activities to which the soul is suited only in order to assure to the body its existence.

Prudishness encourages a repression that is dangerous for those moments in which the soul, bound to participate in the life of the body but no longer taking its inspiration from reason governing the real, tumbles into the opposite excess of wicked participation. The spirit is swept away by the violence of emotion because it never learned to participate in a healthy way in the emotions inseparable from the taste of the apple and the savor of the fruit and of well-being, appreciated without being allowed to overflow dishonorably into roles they are not meant to fill.

The prude is a moral cripple by his ignorance of reality; he is all dressed up as an advocate of the spiritual but is only a pitiful counterfeit. The mentality of a prude renders a normal life impossible, in the name of an imaginary dignity.

There are cases commanded by reason and basic prudence which impose a realistic action-action the prude would heartily denounce as immodesty or vice. I was careful to say "commanded" by reason and therefore morally virtuous despite an activity which is materially immoral. There is the amusing example of the seminarian who jumps in the water in full cassock to save a young lady, clad in just a bikini, who was about to drown and the scolding he received from his most saintly superior, to whom he mischievously replied: "Have no fear, Father Superior; the young lady was in my arms but not in my heart." Everything depends on our understanding the goal without prudishness, and on our willing the goal without dishonesty or deviation.

Could it be that the most prudish epochs in history were secretly the most riddled with vice? That would be an interesting study.

The Sense of Decency

The sense of decency or shame is not a virtue, but a natural or acquired disposition that comes to the aid of virtue. What is the nature of this disposition?

It is a spontaneous expression of the delicacy of the spiritual and higher faculties, anxious not to profane their integrity by obligatory or useless realism and refusing to stoop down to merely carnal expressions of sight, touch or gesture. It is the attitude of a sensibility eager to cling to the spirit rather than to know itself flesh. The sense of decency expresses a dignity determined to exist and a formal refusal of any vulgarity that could dull or deaden it. It comes from being used to living on the summits of a mentality worthy of the heart and mind. The sense of decency perceives the danger before it materializes; it flees from danger, not from cowardice but from the intense freedom of the soul choosing always what is most favorable to avoiding what is base. It expresses a respect for self and for others out of a concern not to be a mere animal for oneself or for others. Consequently, in our social life, it is the sense of decency that fosters refinement of feeling, delicate courtesy, and the very pure joys of the heart. It preaches the spiritual.

The lack of a sense of decency betrays a certain abdication which accepts a closer resemblance to the behavior and the attitude of animals. It is the symptom that you have in fact chosen to follow animal instinct as your reason for acting. It is a forerunner of impurity, and betrays an ignorance of the fact that people who see you have enough delicacy of mind and psychological health to be wounded by your lack of dignity and vigor.

When nudity is no longer commanded by reason and conscience together, it becomes useless exhibitionism, and we fall from the moral dignity of governing our body into the demeaning cult of the body. It is a worship of the body which is full of a false dignity because it stifles the manifestation of the soul, mistress of a spiritually legitimate demeanor.

The sense of decency can be defined as self-respect. Now, the self is both a duality–soul and body–and a hierarchy–the soul above the body, or the body in the service of the soul. It is inscribed in natural law–even animals possess a certain instinctive sense of shame. It goes before purity and ensures to it the exercise of its rights and its duties by preparing the reason to maintain control over real, physical activities, commanded by the conscience, in relation to ourselves or to others.

The sense of decency accompanies real, or physical, activity by the discretion it imposes: the surgeon who is operating and the patient who is naked can very well act with unoffended decency without having to close their eyes! What it does not want is any compromise of our moral and spiritual integrity, more precious than anything.

When clothing, demeanor, entertainment, etc., spontaneously give to someone who is balanced, master of his reason and his soul, the impression that priority is unnecessarily given to sensuality, then there is absence of the sense of decency.

When, abruptly or progressively, fashions, games and pleasures start to destroy our taste for healthy thinking, our spiritual attachment to duty of state, our attention to the dictates of conscience, the need to maintain ourselves virtuous, the sense of honest effort, and our taste for God: then decency is no longer the inspiration for our behavior. We have begun giving precedence to the world, which is the sign that the soul no longer has any instinctive defense against sensuality.

How many parents and young people no longer consider the question of dress, pleasure or demeanor except in function of whether "it's cool," "it's in style," "it's the latest thing," without at all realizing the state of spiritual baseness and of carnality to which they have fallen. No longer to sense the gap between dignity and fashion is to betray the animalization of your heart.

"Show to him who would fear the fortress too high That it's only his heart which is too low." (Au gré des flots –Texier)

Exhibitions of nudity are in keeping with a bewildered conscience in full flight; with a conscience that has slunk back down into the sewers somewhere far below the spiritual beauty of man.

The absence of delicacy, as expressed by the false delicacy of a style strictly concerned with the body, is a sign of mental perversion and of an intellect extinguished under a flurry of kisses, caresses, contortions, and barbaric fashions. The death of shame announces the disappearance of the sense of decency; it marks the appearance of the jackal on the hunt for tainted meat.

Purity

Purity is the positive virtue of real or realist action. It draws all of its vigor and decisiveness not from denial, nor from fear, nor from formalism, nor from scrupulosity, but from a free knowledge, because it is full of grace (Ave Gratia Plena), of the rightfulness of the decision to act, basing itself on a virile and healthy understanding of the act willed and chosen as best, in spite of its materiality. Purity bursts forth from a mind strengthened by integrity and grace, just as light bursts forth through a prism untarnished and unbroken. A moral state of purity arises from a clear knowledge of what remains pure in a given action, which may seem impure but which is only real or necessary.

The starting point for purity is a healthy education in the natural law and supernatural duty, with a concrete application coming from an integrity keeping a close watch over behavior without ever allowing it to deviate and follow instinct to the detriment of the soul. It lets instinct play its proper role, as set out by its knowledge of a necessary reality, but it never permits instinct, with its appetite for pleasure or sensual emotion, to be the sole inspiration of an act.

Any corporal activity is necessarily a blend of mind and instinct. Duty lies in obliging both to stay within the boundaries of their mission. The goal of instinct is to feel: you force me to hold an ice cube in the palm of my hand by keeping me from opening my fist, so, voluntarily, I squeeze my hand tighter to feel the ice even better. Cum sentire: instinct was limited to a certain animal sensation, but now I sense the same thing by the participation of my will. Purity does not forbid sensation to accompany a necessary act; but it does forbid the mind and the will to cede their proper role to instinct. The shore does not forbid the waves to break at its feet, but it never invites the waves to come flooding over it.

The general law of purity therefore requires that knowledge always maintain a loyal, supernatural control over its decisions. In practice, the general law adjusts to circumstances, yet always in view of the general obligation. Purity is not received simply by education. It is in fact the most noble way to gain mastery of ourselves to the benefit of God's life in us. Its importance also arises from the results of its contrary, impurity. In de-spiritualizing man, impurity separates him from God, from his spiritual destiny and from his present occupation of enabling the definitive reign of the soul in man's actions.

Purity therefore presupposes above all else an intelligent and firm education of the child, in order to avoid forming children who are unbalanced, scrupulous, fearful, curious, morbid, or perpetually anxious, and to avoid ending in an explosion of instincts kept packed down and undisciplined by years of prudish coercion. Above all, banish ready-made, one-size-fits-all explanations. Then, explain without mystery but not without delicacy. Teach the child how to make decisions purely, and make him understand the benefit of prayer and the life of the sacraments. Finally, never consider the case at hand to be irreparable.

To educate a child to purity, do not simply abstract; know and understand the psychology and temperament of the child to whom the lesson is directed. Do not cheat a question by taking an escape-hatch, but answer it with a truth adapted to the child's age and emotional development, as a doctor would adapt a prescription to the size and shape of his patient. Finally, show him that purity is not the privilege of a particular class of society, or of a school of thought, or a human conception of life, but that it is inherent to the dignity particular to man. Remember that a child is all instinct, otherwise he would not be a child, and hence the absurdity of treating adolescents like grown men. Why not treat all adults like wise old men?

Teach the child to dominate his instinct by reflection, nourished by an enthusiastic spiritual life that strives for an ideal. Never excuse any yielding to instinct; remember that to punish is to love, when reasoning with him is fruitless. Encourage him toward noble, generous, and beautiful activities in which the quality, excellence and perfection of the mind appear. Instill in him a passion for one of these. Show him that a decision never involves only his body but also his heart and soul and conscience; make him realize the grace that dwells in him and the relationship he should form with God. Finally, make him understand that sacrifice is not meant to traumatize him but to liberate him from the chains of his instincts, constantly jerking him here and there, by voluntarily placing them back under the control of his will through privation and endurance, or through an effort, or through a confession.

Deprived of that education, a great many calls to moral grandeur–a vocation to the religious life, to the priesthood, to the military, to heroism–have suffocated during the years of instinct which stifled the freshness of the soul. Wilted by sins of the flesh, his soul has lost the taste for interior beauty and turned away from the ascensions that alone could have made him a man.

To be pure is to begin life by a recovery of the strength that we lost with original sin: a spiritual strength animating our decision in the use of corporal forces in order to maintain them subordinate to our spiritual growth.

- The real is pure; Unreasonable realism is impure.

- The necessary is pure; The imprudent useless is impure.

- Active or passive prudence is pure; Carnal impulse is impure.

Purity manifests itself by an authoritative reserve toward all that touches the dangers of instinct. It is an intelligent and free reserve, which is the contrary of ignorance or formalism. Its mission is to guarantee the intense interplay of the mind, the superior faculties and sublime, enduring sentiments. It is not a list of do-not-do's roared out by moralism; it is an imperious invitation of the love of God calling us back toward the possession of His own way of loving.

And how did He love?

He loved in associating the sense laws of His body to the imperious immolation which His soul and His Divinity, from Christmas all the way to the Resurrection, imposed on the instincts of material possession, of well-being, of pleasure, of easy, automatic satisfaction of the natural sense life, even unto the voluntary martyrdom of His crucified body.

In so doing, He reminded us that there are two ways of loving: The first is to follow the laws of instinct without letting them infringe on the rights of morality and the soul; and the second, to immolate those very laws under the superior demands of the spirit to the benefit of the general resurrection of men, redeemed from their sensuality and their vices, from their animality and their baseness, by the heroism of personal sacrifice and by the example it creates for each one of us.

The Moral Authority of a Man at Peace

It is six o'clock in the evening in this beautiful month of June, and my 20 years have only just come to know the prodigious balance that a soul rebuilt by forgiveness can savor in a pacified body. Inside me, everything is daylight, calm as a summer night. I can sense that my return to God has destroyed nothing of that beauty to which I succumbed, a little like a young animal who let himself be tempted by the bait...But this return is a stepping into broad daylight, illuminating the hierarchy of things and beings and giving me henceforth a wild desire to respect them with infinite discretion; not to fear them or deny them, but to set them never again in disharmony with my heart, so weakened every time I have senselessly let my senses grow. Inside me, everything is resplendent with the beauty of God's daylight: an untouchable beauty, and so true that it cannot be expressed in words, but can be seen with a soul which has become again a mirror of God. I sense that I am ready to live, ready to love with nobility, ready to struggle, ready even to die, because I possess in my being the strength of a stability the peace of which has enchanted me even to the strength of sacrifice.

How I can now pity those who are truly "seated in the shadow of death"–of their own spiritual death, whose disorders they cannot even see, since they are covered over by the accursed darkness; disorders which can only be seen in their true, horrific value, by the light of forgiveness, giving back the sense of a beauty that makes you pray, that makes you act, and that even makes you weep for joy, as I do this evening.

Dilexit Eos*You love us the way we are You didn't come here to dust off angel wings, He who does not struggle does not know You,

* Jn. 13:1. Ante diem festum Paschae, sciens Jesus, quia venit hora ejus, ut transeat ex hoc mundo ad Patrem: cum dilexisset suos, qui erant in mundo, infinem dilexit eos.–Before the festival day of the Pasch. Jesus knowing that His hour was come, that He should pass out of this world to the Father, having loved His own who were in the world, He loved them unto the end. |

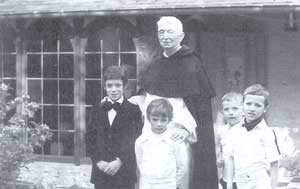

Translated exclusively into English for Angelus Press and published in this language for the first time. Fr. Bernard-Marie de Chivre, O.P. (say: Sheave-ray') was ordained in 1930. He was an ardent Thomist, student of Scripture, retreat master, and friend of Archbishop Lefebvre. He died in 1984.