THE ROAD TO ST. JAMES

|

|

|

Logrono. Church portal of Santiago el Real. This portal depicts St. James as the Moor-slayer (17th-century statue).

|

Walking across north-western Spain, enduring fatigue of body, limbs, back, and particularly of legs that such prolonged marching on uneven roads entails, the pilgrim on the famed pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela–to the tomb of St. James the Apostle–embodies an activity that holds a central role in the holy Roman Catholic Faith.

The rediscovery of the apostle's tomb in the early ninth century in the most remote and obscure region of early medieval Spain led to one of the most popular manifestations of spirituality in medieval Europe. St. James the Major, the brother of St. John the Evangelist was martyred in A.D. 44 in Jerusalem. According to tradition, his body was transposed miraculously to Spain to Iria Flavia, now called El Padron, upon the borders of Galicia. James's disciples confronted the ire of the pagan queen of the region in the spirit of meekness, and worked her conversion to the Faith. She donated her palace as a burial place for the apostle, endowed it magnificently, and spent the rest of her life doing good works.

Between the fifth and ninth centuries, the apostle's tomb was almost forgotten. In A.D. 711, Tarik-Ibn-Zaid at the head of Islamized Berber tribes (Moors) crossed the strait, known as Gibraltar, beginning eight centuries of Moorish occupation and domination.

A century later in about 813, heavenly consolation came in the form of a star perched on the Libredon Forest in Galicia. A hermit by the name of Pelagius sent word to the local bishop who, led by Pelagius, headed for the forest and in its thickets discovered an old Roman-style chapel. On examining the crypt, he corroborated the astonishing discovery and without delay declared it to be the tomb of St. James, or Santiago, as he is called in Spanish, the protector of Spain. He ordered a church built with an adjacent monastery. Around these a town came into being, afterward known as Santiago de Compostela, a name which some say stems from compositum, or cemetery, and others from the vision of Pelagius, which led the site to be called Campus Stellae or "the field of the star." From that time on, Santiago de Compostela grew as a celebrated shrine and destination of pilgrims, ranking in importance alongside Jerusalem and Rome.

The cult of Santiago flourished, and major historical consequences for Spain and Christianity ensued. Following the invasion and conquest of the peninsula by the Islamic Moors, the Christian resistance was reduced to a remnant in the Cantabrian Mountains of the far north. The remarkable news of the unearthing of Santiago's remains, however, proved to be a turning point for Christian morale. The legendary battle of Clavijo, near Logrono, in the Ebro Valley in 844 saw the intensification of the crusade against the infidels known as the Reconquista. Out of it would be born one of the central themes in the tradition of Santiago as defender of the faithful.

The Moslem princes from their capital at Cordoba had been accustomed to demanding 100 Spanish virgins as a yearly tribute. The king of Galicia, Ramiro I, at length refused to comply with the disgraceful exaction and put together an army to engage the superior Moslem forces. During the night, Ramiro had a dream in which Santiago consoled him and assured him that the Christians would be victorious, their losses minimal, and he himself, as protector of Spain, would participate in the battle. The following day, Rodrigo's men returned to the field and engaged Abd-ar-Rahman II and his men. Sure enough, in the savage fury, just as he had promised, Santiago appeared on a galloping white horse, with a billowing cape, sword in the right hand, swinging a mighty sword, and slew the warriors of Mohammed to the number of 60,000 or more. Inspired by the presence of their patron saint knee-deep in blood, Ramiro's soldiers swiftly came in to complete the job. In so doing, they cried out the name of Santiago, using it for the first time as a battle cry. Henceforth the cry was voiced in every confrontation with the Moors. It was at this time, too, that the apostle came to be called Santiago Matamoros, St. James the Moorslayer.

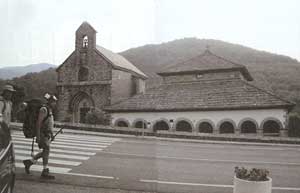

Roncesvalles. Charlemagne's Silo, Capilla de Sancti Spiritus

where the crypt was used as an ossuary for pilgrims who died in the hospital.

It is said that this is the site of the tomb which Charlemagnes had built for Roland

and the soldiers who were killed in the Battle of Roncesvalles.

In his role as defender of the faithful, Santiago Matamoros is reported to have appeared 38 times in Spain over the next five and a half centuries in the all-consuming crusade against the Moorish invaders in Spain. It was during the pontificate of Urban II that the first crusade to the Holy Land was proclaimed; but that was more than 30 years after the Spanish struggle against the Moors, the Reconquista, had been formally classified as a crusade by papal decree. In the crucible of the long, bloody struggle with Islam, Spaniards toughened their faith and produced a pride of character that their special relationship with Santiago nurtured.

Relics and Pilgrimages

The pilgrimage road, both in ideological as well as in concrete terms, provides the pilgrim with a striking parallel to the road to Calvary, the via dolorosa, that Christ Himself undertook on the way to His crucifixion. During the Medieval period, when altar and throne were united under our liege Lord, the habitual framework of devotional practices in that society conditioned their attitudes and religious practices. That life itself was a pilgrimage gave rise to pilgrimages as a characteristic form of religious expression. The Church in Pope Urban II's time began to sanction formal recognition of a saint's intercessional powers when visited by a pilgrim, granting certain indulgences. The first Roman Jubilee with a plenary indulgence was begun by Pope Boniface VIII in 1300. The relics of holy figures and their intercession strengthened in proximity to their tombs-sustained the wearied pilgrim after weeks and months of walking.

As Dante asserts in his Divine Comedy, there were three main pilgrimages in western Christendom: romeros were those who visited Rome; palmers were those who went to the Holy Land; and pilgrims were those who arrived at Santiago de Compostela. Within the ranks of devotional pilgrims there were those who went to Santiago simply orandi causa, in order to pray, as well as to beg at the tomb of the apostle for recovery of physical well-being. These pilgrims went to St. James the Miracle-Maker. The act of pilgrimage, once a force in the West, had as its goal, then, the visual and tactile contact with the sacred relic. The ideal pilgrim makes his weary way to see the saintly remains, to touch them. Even if the relic itself cannot be touched, one touches the reliquary casket or the sarcophagus. By the late 12th century, the route, known variously as the via jacobea, or camino frances [since it wound through southern France before crossing the Pyrenees–Ed.], was well-established in northern Spain, while in the rest of Europe the ancillary routes and local places of devotion were adding their special identity to the many attractions of one of the principal shrines of Christendom.

Burgos, the magnificent Gothic cathedral,

the first stones were laid in 1221 by King St. Fernando III.

The grandiosity of its architecture and the richness of its interior decoration

combine to make Burgos Cathedral one of the most outstanding artistic monuments in Spain.

The unceasing flow of pilgrims to and fro on the Camino de Santiago created new demands. Royal charters in the ninth century began to refer to pilgrims as beneficiaries of the donations, and the first signs of hospitality made their appearance. And to serve the throng of pilgrims, churches, monasteries, convents, inns, hospitals, and bridges came into being. In 1170 the military religious Order of Santiago was created by order of Fernando II of Leon (1157-88). Like two other Spanish orders, Calatrava and Alcantara, it merged the ideals of monasticism and chivalry while promising to defend Christendom against the infidels. Standard records have long maintained that the primary duty of the Knights of Santiago was to keep the pilgrim road free from Moors and bandits. The Grand Master of the order signed an official agreement with the archbishops of Santiago de Compostela in which his men declared to be "vassals and knights of the Apostle St. James," and the archbishop, in a reciprocal manner, became an honorary member of the order, bestowing on it a banner with Santiago's picture to be carried into battle.

All of these orders took on a major role in the Reconquista. The Order of Santiago became eventually the largest, most prestigious, and richest of these religious bodies. It protected the major frontier castles, ransomed Christian captives, managed cities and towns, ran hospitals and convents, and even sponsored a college in Salamanca. When summoned, the Grand Master could lead into the field an army of 400 mounted knights and 5,000 footmen. The distance covered by a pilgrim on a daily basis is based on the conditions of the road. For the most part 12-15 miles is a reasonable average daily march; but there are certain mountainous stretches in which no more than nine miles are made.

The landscape in northern Spain features the Meseta, the elevated central tablelands of Castile and Leon. The distinctive Meseta is noted for its high, unending, rolling, steppe-like plains, where sheep and wheat are a source of wealth. Water is scarce, and livelihood has been hard for man and animals since the days when the forests were cut away. On leaving the borders of Leon and entering Galician territory, the somber rigors of the Central Meseta is contrasted by rich valleys surrounded by high mountains, almost appearing like a Celtic paradise.

Any pilgrim to Compostela around 1100 would have found churches in the Romanesque style along the pilgrimage route. As a result of a new prosperity and vitality in Europe in the second half of the 11th century, Romanesque culture evolved all over Europe. The stonemasons on the Jacobean Way, heirs to the ancient builders, who proudly guarded the secrets of architecture, created Spain's most beautiful monuments. The unique monuments on the road to Santiago refer to shrines like the cathedrals of Compostela, Leon, and Burgos, or the churches of San Martin de Fromista and San Isidoro de Leon. The "Roman-looking" shrines, larger and more richly decorated than any of their predecessors, are accounted for by the introduction into the Hispanic kingdoms of the Roman liturgy.

The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, begun in 1075, celebrated for its possession of the relics of St. James the Major, was no exception to Romanesque architecture. Like other pilgrimage churches grand in scale, it was built in granite, fortified, and has remarkable sculptural decorations. Flanking side aisles continue around the apse in order to create an ambulatory for crowd flow, coupled with nine chapels which were consecrated in 1103; the final consecration came a century later in 1211. Up to the early years of the 12th century pilgrims could venerate directly the tomb of St. James. At some later unspecified date, it was put away under the main altar. Although it was extensively altered in later periods, the great core of this splendid old cathedral is still dominant underneath an icing of Renaissance and Baroque decoration.

The presence of both civil and ecclesiastical dignitaries from all over Europe at Santiago de Compostela conveys the international fame and curative power of the shrine. Intermingled with the crowds of anonymous pilgrims who followed the road were some great figures: William X, the Duke of Aquitaine; Countess Matilda, widow of the German Emperor Henry V; Louis VII of France; Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony; St. Francis of Assisi; St. Dominic of Guzman; St. Isabella of Portugal; the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabel; the Catholic Kings Charles V and Phillip II; as well as Don Juan of Austria. In 1908, the future Pope John XXIII also did the road on foot, and subsequently traveled to Compostela in 1954 when papal nuncio in Paris. Pope John Paul II's journey to Santiago in 1989 was the first ever by a pope.

Saint of Two Worlds

The discovery of the New World, under the patronage of los Reyes Catolicos (the Catholic Monarchs) Ferdinand and Isabel gave the Spaniards a new, holy mission–to cross the Atlantic and spread the Catholic Faith to heathens.

Spanish explorers and colonizers, under the special patronage of Santiago, confronting Indian resistance, from that of the advanced and populous Aztecs, Mayans, and Incas to the lowly Caribs and Chichimecas, bore their monumental hardships with equanimity. Coming off their victory over the Moors at home, the Spaniards also enjoyed a strong psychological advantage. Had not their cross vanquished the crescent of Islam? Invoking his name and uttering their spirited battle cry, Santiago y a ellos! ("St. James and at them!"), they credited the saint with many of their astounding triumphs. His most visible legacy throughout Latin America, though, can be found in place names. Spaniards gave 81 settlements in New Spain (modern Mexico) the name Santiago. In Peru, the figure was 23, and so on throughout the kingdoms and regions. These plain numbers simply reaffirm how closely the Spanish mind identified with the Apostle James and how eager were the colonists to honor him.

The cult of Santiago in turn spread among the conquered Indians. Wherever the apostle was assigned as the patron of an Indian town, precinct, church, or mission, the indigenous people displayed an enthusiastic allegiance to his name and ceremonies. The month of July, known in Spanish as El Mes de Santiago, was devoted to his honor as shown by the native people, who celebrated with music, dance, fireworks, games, and horse races.

Sightings of Santiago in the Americas, reported in some 13 well-documented cases, confirmed his patronage of the Spanish cause. One of his most conspicuous appearances occurred in one realm within the Spanish Empire–in the present southwestern United States. More than four centuries ago, Don Juan de Onate (c. 1550-1626), a wealthy silver magnate and the first ruler of New Mexico, whose wife was a granddaughter of the explorer Hernan Cortes and a great-granddaughter of the Aztec emperor Montezuma, signed a contract with the Spanish Crown allowing him to colonize the Kingdom of New Mexico. After rumbling northward across desert and plains, the great wagon train of settlers forded the Rio Grande at what is now El Paso, with 300 Spanish-speaking settlers, and eventually reached their destination in 1598 in the Espanola Valley, some 20 miles north of the future city of Santa Fe.

|

|

|

The sanctuary of the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela with the statue of the Apostle James in the center above the altar.

|

A year later disaster struck. Onate's nephew and second-in-command, Juan de Zaldivar, and some of his men were set upon by the Acoma Indians and slain. Governor Onate responded quickly by sending a force of 70 men to subdue the pueblo. The Spaniards, animated by the legacy of their crusading grandfathers, eventually forced the Acomas to capitulate. The Indian survivors asked to be shown the big, noble Spaniard who had been at the head of the battle and had swept through their ranks. He was on a white pawing steed, they said, and he had a flowing white beard and carried a mighty sword in his right hand. This warrior was also joined by a maiden of incomparable beauty. The Spanish men-of-arms, in bewilderment, while having seen nothing of this, knew instantly that Santiago and the Virgin Mary had come to their aid.

To commemorate Onate's momentous crossing of the Rio Grande, the city of El Paso, Texas, is planning to unveil the largest bronze equestrian statue in the world: an armor-clad conquistador on a horse three stories high, rearing above the border between the United States of America and Mexico (see cover of magazine). The statue, excluding the base, will weigh six tons. The historical significance of Onate in opening up the American southwest to Hispanic culture, enduring incredible hardships in a hostile world, reflects the fervent devotion to Santiago of these early Spanish colonists. For the Hispanic people in New Mexico, the Apostle James continues to be an emblem of potent and knightly manhood. The Venerable Bede once said that James "spoke so loudly that if he thundered but a little more loudly, the whole world would not have been able to contain him." The cult of St. James the Major has proven indestructible. For centuries believers have sought to become beneficiaries of veneration by marching to his tomb at Santiago de Compostela. Strengthened by grace on this via dolorosa, a pilgrim to his shrine shows himself a miles Christi, a soldier of Christ. Just as Santiago Matamoros roused up the beleaguered Christians in their fierce battles with the enemies of the Cross, the activity of pilgrimage–once a force in Christendom–to his shrine in northwestern Spain identifies the pilgrim as a devotee of St. James, who "offers strength and consolation in the unending warfare in this life, that having constantly and generously followed Jesus, we may be victors in the strife and desire to receive the victor's crown in heaven."

Mark H. Jurado is a 1991 graduate of the University of California, Berkeley, with a major in Psychology. He also holds two Master's degrees in Psychological Counseling from Columbia University in the City of New York. He spent two months in northern Spain this summer on pilgrimage. The pictures used in this article were taken by his father Henry. They assist at the Latin Mass at Jesus and Mary Church, El Paso, Texas.

Melczer, William. The Pilgrim's Guide in Santiago de Compostela. New York: Italica Press. 1993.

Bravo Lozano, Millan. The Pilgrim's Road to Santiago: A Practical Guide for Pilgrims. Spain: Editorial Everest, S.A.. 1998.

Myers, Joan, et al. Santiago: Saint of Two Worlds. Albuquerque: Univ. of New Mexico Press, 1991.

Tate, Brian & Marcus. Pilgrim Rome to Santiago. Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1987.

Lobato. Xurxo, et al. El Camino de Santiago. Spain: Lumverg Editores. S.A. 1988.

De Voragine, Jacobus. The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Trans. William Granger Ryan. Volume II. Princeton., N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Butler. Alban. The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Saints. Montana: St. Bonaventure Publications, 1997.

The Raccolta (1957). Powers Lake, ND: Marian House.

Thompson. Martin. "The Shock of the Huge." The Sunday Telegraph (London, England), September 9, 2001, p. 5.

Abram, Lynwood. "A Monumental Task," Houston Chronicle Magazine (Houston. Texas), April 22, 2001, pp. 8-12.