The Era of Illumination

St. Augustine, the Book of Kells, and the Preservation of Sacred Text

Gerald L. Browning

In the year A.D. 563 a group of monks, probably about 12, set off from Ulster in Northern Ireland in a leather-hulled sloop, bound for the rugged shores of the Hebrides, a barren rocky archipelago off the southwest coast of Scotland. Paul Johnson in the History of Christianity writes that they wore long, white bleached, flaxen habits, carried curved staffs, liturgical books in waterproof leather bags hung on their belts, and around their necks they hung pouches for water and bread wafers.1

At the helm of the boat stood Columba, a great monk who would guide them on their journey to build a new monastery on what Longfellow would later refer to as that "tempest haunted outcropping on barren stone."2 Columba would name it Iona in memory perhaps of the ancient Greek cities of Miletus and Ephesus of the sixth century B.C. from which it is thought, the natural philosophy of men such as Thales and Pythagoras originated.3 Iona would be his home until his death in A.D. 597, and would become one of many significant outposts of the Irish Celtic Church both on and off the shores of Europe. Not until Christmas Day in 986, when the last attack of Danish invaders had struck at its heart, would the stone enclave at Iona cease its monastic functions and turn inland, toward more secure environs.4

The monks who lived and worked at Iona were part of a missionary impulse whose roots were planted many centuries before, during the time of the last Roman Caesars when the great empire was finally expiring and only its spiritual and cultural legacy was left intact. The eternal city Rome stood proud and straight, although expressionless, as waves of Barbarians swarmed around it. Its growing Christian population, long since numbed by corruption, depravation and purging, looked to the Catholic Church for purpose and direction. They would find it in the teaching and writing of men such as Sts. Jerome, Ambrose, and Augustine.

Prelude To Illumination: St. Augustine And The City Of God

|

|

The social and political disorder of Rome in the fourth century AD and the subsequent rise in its place of the Roman Catholic Church was such that it gradually assumed a position of social-religious pre-eminence that would help it survive the social chaos that would infect Europe for the next half millennium. It was not until the reign of Charlemagne in A.D. 800 that some semblance of political stability and social order began to re-emerge in Europe, and as a result an institutionalized Church began to grow and prosper, the one under Alcuin at Tours being an excellent example.

Before that, the inspiration for the advancement of Christian theology was in the hands of a few men. Religious teachings and sacred texts were usually written in Greek or Latin and were confined generally to the secular or religious elite. Men such as Ambrose of Milan who preached in the mid to late 4th century were immensely popular because they brought an oral message from God that common people could understand. His church overflowed with the faithful, satisfied and uplifted by his oratory. They had no Bibles or prayer books, but they hung to his every word in spite of the renewed Christian persecution that was going on around them. St. Augustine, a student and later a disciple of Ambrose, reminds us of one particular sermon:

...and all our minds from anguish ease and our distempered grief appease that so when shadow round us creep and all is hid in darkness deep, faith may know of gloom and night borrow from faith clear gleam, new light5

It was this new light, this inspiration from God, that St. Augustine would use to reflect the beauty of Christian life, and through his teachings to help people understand that there existed a distant place that could be arrived at through faith and discipline, and that this place was heaven. In doing so, he was able to bridge the divide between the years of the fall of Rome and the beginning of Europe's recovery 500 years later. St. Augustine's message was one of illumination, a Zeitgeist of heavenly light that would find its way into the scriptoria of scores of monasteries throughout Europe and which would result in the creation and preservation of the sacred messages of God and his disciples.

St. Augustine of Hippo was born in the city of Tagasta in eastern Numidia in A.D. 345. As a young man he was influenced by Cicero, especially his Hortensius, which St. Augustine would say gave him the impetus to achieve wisdom, and later by Plotinus, where he first learned about "Logos," the eternal word that is God.6 It was this "Logos" that would inspire his lifetime of writing, and provide the foundation for his articulation of both those things holy and those things human, and with regard to the latter, the temptations of "carnal corruption...and the briers of unclean desires"7 that he fought so strenuously against throughout his life.

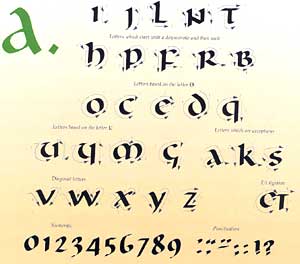

It is compelling that at about the same time (A.D. 387) that St. Augustine was receiving his baptism from Ambrose, the newest and most complete Latin version of the holy Bible was being introduced by St. Jerome. Written in what would become known as the uncial style (see Fig. A. see p. 19 and bottom of this page), an intricate and elaborate calligraphy emphasizing capital letters and beautifully adorned with colorful iconographic drawings, it became the basis of future religious writing throughout Europe.8 Its origins lay in the formal scripts that had evolved during the Phoenician era and had matured through the Greek, Etruscan and early Roman periods, finally culminating in the Roman Square Capital which can be found on many Roman columns and statuary [see top of this page–Ed.].9

St. Augustine would employ a version of the Roman Square Capital in his own writing. Here an emphasis was placed on speed and precision, with the beginnings of forms of punctuation to increase comprehension and functionality. This was due in large measure to the need to satisfy the growing demand for religious writing. The script was in fact clear, easy to read, and easy to copy. It would help to "spread the faith"10throughout the old empire. He was probably influenced by the Roman linguist Celius Donatus who employed the grammar and style of Cicero and Virgil in his writings.11 St. Augustine wrote voluminously on virtually every subject, secular as well as religious. His methods of writing, as well as his subjects, were important because they needed to be painstakingly copied and distributed throughout monastic schools and churches. A feverish period of writing ensued during the Augustinian period, as scribes sought to preserve sacred as well as secular texts in the face of the Barbarian onslaught. The fall of Rome signaled to some a second version of the fall of man. Rene Fulop-Miller in his work The Saints that Moved the World has theorized that St. Augustine's writings "secured the survival of the Catholic Church."12

The message of St. Augustine, thus fortunately preserved throughout the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries served as the catalyst for the rapid growth of monastic scriptoria throughout Europe. St. Augustine himself received his formal education in a monastic school. Lay schools were in a state of decline due to the dual dangers of renewed persecution of Christians at the hands of both Roman and Barbarian tyrants. The monastic school, somewhat isolated or removed from public view, was at least a safer place to preach, learn, and write. Cassidorus, teacher to the Ostrogothic ruler Theodoric the Great, established his own monastery at Vivarium, in the Ionian Sea in A.D. 540. He thus joined others of the period such as St. Martin at Tours, and St. Benedict at Monte Casino, who had either inspired or actually constructed schools throughout the Mediterranean.13

|

|

|

Pictures reproduced with permission from the Board of Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland

The Augustinian philosophy is instructive here because it serves the dual function of creating the intellectual as well as the religious basis for the growth of monastic writing centers during the later period of the first millennium. Certainly significant colonies of monks had existed prior to the Augustinian period, but their work to a large extent consisted of liturgical activities rooted in physical isolation, and whose purpose was usually to conquer impurity.14 Now there was another reason to please God and it took the form of illumination; illumination in building churches, in producing holy objects, and in copying religious writings, especially the Bible. St. Augustine wrote that "the Bible is what God has kept from the wise and revealed to the simple and innocent."15 As monasteries grew and prospered in Europe, villages and towns grew around them. Peasant labor was crucial for the monastery's survival. If the monks were inside copying the gospels, then the farmers were in the fields herding the animals that would be used for making vellum, the paper used in the scriptoria. The monastery would in fact become the "City" that St. Augustine so laboriously dwelled on, a city of men living and working in the service of their God. St. Augustine uses Corinthians to underscore the monks immense responsibility:

And so long as he is in this mortal body, he is a pilgrim in a foreign land, away from God, therefore he walks by faith...with compassion in taking care of others...and so collects a society of aliens, speaking all languages.16

The last three words of this passage are essential in understanding the monastic message of St. Augustine. Speaking all languages might mean speaking the one or universal language of God. God's light would illuminate all men, irrespective of their origins. St. Augustine's use of the word light as a medium of spiritual uplifting is found often in the City of God. He describes it as "the intelligible illumination of truth."17 In another description he sees light as "the Holy City which consists of the holy angels and the blessed spirits."18 Monks working in the deep, dark dungeons of medieval monasteries would become the transmitters of this new light. St. Augustine's depiction of night is particularly interesting when seen through Scripture. In a foreshadowing of the confidence he felt in the future of man he quotes: "And in fact Scripture never interposes the word night....Scripture never says night came; but evening came, and morning came; one day..."19

The words "morning" and "day" and "evening" suggest light while night suggests darkness. Years later, when the scriptoria were in the full bloom of verse and color, the monks might perhaps remember the words of St Paul: "But if we are hoping for something we do not yet see, then it is with steadfast endurance that we await it."20

Unlike St. Jerome, who saw the death of Rome as the death of the human race, St. Augustine had confidence in the future of man. The City of God would be the fulfillment of God's love, a redemption rather than a fall. In his Book on Happiness, St. Augustine speaks of the "way of Providence, which uses the storms of adversity to bring men, resist and wandering as they may, to the same harbor."21 He uses a verse from Ephesians to capture the moment when those monks under Columba first knelt on the stone gray shores of Iona and kissed its soil: "Good angels are called light. Men...you were, he says, darkness in the past; but now, in the Lord, you are light."22

The Augustinian model of monasticism also contributed to another powerful cultural dynamic that Jean Leclercq in his work The Love of Learning and the Desire for God has described as the "monastic style." This was a way of life richly embued in writing as well as prayer. Writing was to reflect the beauty of the spiritual life. Monks would refer to his "Confessions" in their daily prayers, and use the pen to turn to sources of ancient culture for their personal enrichment. Leclercq tells us that it was "free and spontaneous...and full of Christian enthusiasm."23 He passes on to us a message from Peter the Venerable who spoke of the life of a writing monk:

He cannot take to the plow? Then let him take up the pen; it is much more useful. In the furrows he traces on the parchment, he will sow the seeds of divine words...and without leaving the cloister, he will journey far over land and sea.24

For Columba, much of his life was a physical journey. When another group of Irish monks under Columbanus landed in Merovingian France in A.D. 591 to establish a monastery at Luxeuil, they brought with them beliefs in the patristic notions of evangelicism and conversion. There existed a certain level of independence within the Irish monastery. Many of them were self-sufficient, clearing land and building walls without much help from anyone else, including the papacy in Rome. Paul Johnson describes these monasteries as entities unto themselves, their ideals having become normative in scope and in practice. "Augustinian in nature, they reflected man's struggle against his baser impulses and they worked diligently with the peasant classes."25 They did not always please Rome with their practices, they eschewed priests and bishops, and in the area of tonsure were particularly problematic, shaving the front of their heads and letting everything else grow. Gregory the Great was so concerned that in 597 he sent his own emissary, Augustine, to England to begin a formal Catholic conversion process.26 Scholars, priests and monks flocked to Ireland to take part in the "insular" tradition of copying obscure works, secular as well as religious. Painted wooden panels and ornate glasswork were brought to the island to be used in its churches. This early art formed the basis for the gradual practice of copying and illuminating sacred texts. Learned men could be creative while they lived in a somewhat self-imposed exile.27 But while they came, others left, venturing abroad to build and write and teach, thus ensuring the legacy of the Catholic Church in Ireland. Columbanus built over forty monasteries on the mainland during his life. Their methods of calligraphy and illumination would form the distinct characteristics of the great gospel manuscripts, including the Book of Kells. St. Augustine beautifully describes what would ensue:

The creature knowledge, left to itself, is, we might say, in faded colors, compared with the knowledge that comes when it is known, in the wisdom of God, in that art, as it were, by which it was created.28

The Scriptorium At Iona

The shoreline of Iona is a patchwork of jagged crags and piled stone formed thousands of years ago.

Its deep red coloring is the result of the vast iron deposits within its veins, cracked and split by the relentless surge of the last receding glacier, so that when the waves pound against the rocks, the foam turns bloody red as it melts back into the sea. The monks would come down to the water often to select soft bits of stone which they would grind and pound with a mortar and pestle, mixing it with vermilion or red rose petal, or perhaps red apple skin, and then finally adding gum and water for consistency. This deep dark pigment or rubricate was used in the headings of the illuminated books. Often the figure of Christ would be outlined in red, symbolic of the blood and pain of His life.29

Pigments were important to the artist for a number of reasons, chiefly because of their religious significance. The aforementioned red has obvious symbolism, while yellow was the reflection of light and would find its way into background scenes. Here saffron was the preferred herb, although the hearts of daisies, each its own tiny sun, could suffice. Green was made simply from parsley and honey. Blue, the most beautiful of all colors, came from lapis-lazuli-a, semiÂprecious stone, valued perhaps more than gold, for it could only be found in the barren, dry wastelands of the Middle East. The favorite color of the kings and queens of antiquity, blue symbolized the soft beauty of youth. The infant Jesus would be swathed in it or the young angel gazing at him would have his wings tinged in soft blue like the sky.30

The scriptorium of Iona would probably have had an apothecary equipped with the various materials used in making paint. Many of the flowers could be found growing on the island's verdant fields. But other items necessary such as pine tar, pitch, and honey which were used as emollients, needed to be shipped in. Chickens were crucial for their egg whites, which gave the paint its brilliance and luster, especially the blues and greens. Added to this were a myriad array of knives, oyster shells (for mixing paints), odd types of burnishing stones or animal teeth for polishing, goose or swan or crow feathers for pens, with their nibs split in particular ways to produce types of bold lettering, jars of pure, fine soot mixed with water to make ink, brushes of varying sizes with their bristles of animal hair tied neatly around a small stick, and finally, locked away, the tins of gold leaf, already having been melted and softly pummeled into thin strips, usually to be used for a cover or title page. In some of the wealthier monasteries, precious gems and silver were used to stud or emboss the books or as clasps or corner coverings.31

The soil of Iona was rich due to the regular amounts of rainfall distributed by the westerly winds. Plenty of grazing land was available to support a small but steady livestock trade, particularly sheep and cattle. Cultivation of land was traditional to the monastic movement. If the monastery was to thrive, land had to be cleared and food grown. While this may have been the case on the continent or on larger islands, in Iona livestock was probably used for producing the skins used to make vellum, which since 600AD had supplanted parchment as the paper of choice for the great books.32 Iona is small, only three miles long by one and one half miles wide, but three quarters of it was used for pasture, the other quarter for cultivating oats, hay, and flowers. Since the best quality vellum came from newborn lambs or calves, it might take an entire herd of 200-300 animals to produce a book such as Kells. Since the monks left few records on the amounts of vellum used, or for that matter, methods of procurement, we may assume that importation of the skin was necessary.33

|

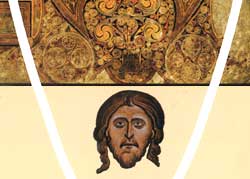

The Chi Rho page is probably the most famous in the Book of Kells.

If the page is arranged a quarter-turn clockwise the viewer can see

the stylized outline of a portrait of Christ with his darkened beard

and rounded eyes through which we can imagine the heavenly bodies of the universe.

Practice in writing and drawing on vellum was important to the insular artist, thus a constant supply of skin from older animals was needed. Thus there probably existed in the scriptorium an area for the drying and tightening of the skins. Initially it would be placed in lime or urine to remove hair and oil, and then shaved of excess hair and oil with a crescent shaped instrument known as a luna knife, and finally attached to wooden frames for drying. Then it would be cut into squares with the left over bits of skin used for practice.34

Within the scriptorium, there was a room reserved for the binding of books. Here the cover, usually older, coarser vellum or perhaps gold leaf, would be embossed with gem studs to avoid scratching, and outlined in silver and gold brocades. The spine would be a rich wood with the quires sewn to it with thin scraps of leather. Some books were sewn so that the stitch work was flush in keeping with the eastern Byzantine style; others were ribbed, which was probably the case with the Book of Kells.35

Novices were usually in charge of mixing paint, sharpening tools, or performing the sundry activities in the scriptorium. The insular artist enjoyed a kind of hierarchical position in his art so, it might be beneath him to boil the water in which tiny balls of lapis-lazuli and wax were emulsified and then mixed with egg white, or to mix the chalk, powder, glue, and honey which formed the base for attaching gold leaf to the edge of the manuscript. When the artist was ready to work it was usually standing up or on his knees, with an easel in front of him and a curved decorated stone draped over the top to keep the vellum in place. At his side were his essential tools: knife, quills, compass, template, ruler, ink, eraser, and polishing or burnishing stones for the gold leaf and color drawings. If he wished he might have hanging nearby a favorite animal tooth for polishing.36 He would almost always work in silence since he considered this a form of asceticism. This was his pleasure. The colors and the language took the place of earthly and physical joys, and they would be served up to the memory of St. Augustine or St. Benedict.37

Ian Barbour in his work Religion and Science reminds us that "God is known through natural and revealed theology."38 Knowledge of God is transmitted through Scripture and particularly through the Church. The Book of Kells became the refined articulation of the Gospels' message. When the monks of Iona fled their home in the early years of the ninth century and moved to Kells in Ireland, they brought with them a book that reflected the highest forms of contemplative art. It was produced as a result of the expansion of innovative forms of calligraphy and insular illumination. The art depicted in the Book of Kells would not have existed were it not for the technological craftsmanship that had evolved centuries before and had been passed on by generation after generation of artists and craftsmen and writers. The scriptorium had become a technological center of production. Nor was the Book of Kells part of an isolated artistic tradition but rather it was closely related to other art forms such as pottery, jewelry, prayer books, and enamels. For instance, the Tara Brooch found in Iona in 1850 is quite similar in its design to the curvilinear patterns on the Chi Rho page (see Fig. D, see p.21). Many of the wands carried by angels on some of the pages are similar in design to those used in everyday practice.39 The tiny prayer books that were distributed in the refectory were often identified with the artists' particular stamp or bouquet (florilegium) and reflected, as Leclercq says, the "imagery of the spiritual garden."40

The Book Of Kells: Insular Illumination

The Book of Kells originally numbered 680 pages with 370 folios or illustrated pages. Thirty of the folios have been lost. The four Gospels form the main body of the text. They are accompanied by a number of pages devoted to canon tables, symbols, and evangelist portraits. For the purpose of clarity and amplification, five pages shall be viewed through the pens and brushes of the monks at Iona.

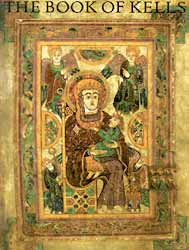

The picture of the Virgin and Child (see Fig. B, p.20) is one of deep lustrous reds and yellows. Because it did not follow any particular Gospel, it may have been what Carol Farr has called an overleaf or dedication page.41 Nevertheless, it is stunning in eastern classical motifs, especially the Virgin Mary with her gold leaf embossed halo, and the gold head covering, and in the linear curvature of her face. If one were to assume that the angels overhead had arrived from the heaven to the north, then she is facing southeast, the seat of religious learning. She is clothed in a red robe, swaddling the infant-man who is reaching for her milk-laden breasts. She is surrounded by angels, two male and two female, each accompanied by various Christian accoutrements such as scepters and wands. And while she sits on a throne of sorts, her pose may be significant in that she is at the origin of the principal moment of Christian theology, Christ's birth. The intricately patterned lace work of snakeheads portends to the future temptations of her child and presupposes His resurrection. Bernard Meehan in his introduction to the Book of Kells saw the snake as "renewing its youth when it shed its skin much like Christ would do when he rose into heaven."42 But Meehan reminds us that the snake also typified the fall of man and his loss of innocence. One is reminded of the Virgin as she holds tightly to her child and attempts to shield him from what will come to pass. Here one sees in a beautifully illustrated painting the love of a mother for her child, especially a child who is destined to deliver mankind from itself. The Virgin Mary gazes lovingly outward, her red robe symbolic of the blood that her son would shed. St. Augustine cites the Gospel of Matthew: "She will bear a son, and you will call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins."43

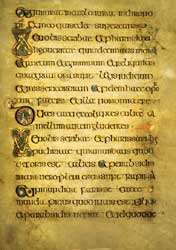

Although the folio of Virgin and Child is without text, the usual method was to include folios within gospel text, folio Breves causae of John (see Fig. C, see p.20) being a case in point. Here we have an elegant representation of the majuscule style of capital letters through most of the page, although the artist, in what might be described as a mood of embellishment, finishes the page with small or miniscule lettering. Meehan has difficulty in explaining this ambiguity as well as the shifting from red to black ink.44

Nevertheless, the writing is stunningly beautiful. Its line segments and spacing are even and symmetrical, which is apparent in much of the Book of Kells. The artist took pains to measure his lines and margins, making sure that line endings included full words much like the formats of present day computers. Periods of sentences are drawn with a wistful swirl and are followed by decorated gold leaf motifs to begin the following sentences. Occasionally the artist loses himself by elaborately emphasizing a particular letter such as the K in line three or the X in line 10 with a simple flower stem and leaves.

The text also underscores the prevalence of animal motifs throughout the Book of Kells. They include snakes, birds, fish, insects, and any living thing that entered the mind of the illuminator. In this particular case, we have a leopard or lion, which according to Meehan symbolizes the "majesty and power of the royal house of Judah from which Chris was descended."45

The Chi Rho page is probably the most famous of all the folios in the Book of Kells (see Fig. D, p.21). Chi and Rhoare the abbreviated Greek for the name of Christ. Characterized by colored inlays of complex intricate design, it is what Sister Wendy Beckett has described in her work The History of Painting as a "wild and controlled paradox of lacelike perfection of linear patterns of geometric complexity."46 The page can be turned around and around and viewed from all four sides. From one particular side (a quarter-turn clockwise), one sees the subtle outline of the portrait of Christ with His darkened beard and His rounded eyes through which we see the heavenly bodies of the universe. Beckett calls it a "kind of floating human face."47 Anthropomorphic and zoomorphic symbols abound, especially the snake and peacock, which at times are entwined. According to Meehan, the peacock symbolizes the "incorruptibility of Christ." Legend tells us that St. Augustine, attempting to verify the Isadorian notion that peacock meat would not rot, let it stand for one month and found this to be the case.

The Chi Rho page like so many others, is particularly red and yellow with inlays of blue. It resembles more a type of jewelry or brooch design than a drawing. Its use of pointing, the practice of punching small patterned holes into the page (which can be seen on the left side) indicates a type of jewelers craft. It may have been a copy of a metal design produced elsewhere. Nevertheless, it is one of the finest examples of insular illumination to emerge from the Middle Ages.49

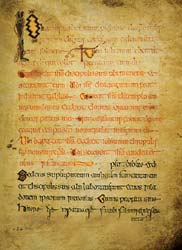

St. Matthews Gospel (see Fig. E, p.20) is another example of the beautiful symmetry of majuscule script. The writing is larger with a greater emphasis on the highlighting of letters which indicates that the artist was highly skilled in that he would not only have had to use a variety of quills of different shapes and angles, but also lifted his hand many times to produce the bold, carefully drawn letters. David Harris in his work The Art of Calligraphy surmises that because of the difference in writing styles found in the book, there may have been more than one scribe working on the book, perhaps as many as four, one for each Gospel.50

The text is a wonderful representation of the use of lapis-lazuli in sentence headings and the use of zoomorphic lion images, outlined in some instances by the pointing effect. Also apparent is the practice of corfa casam or "turn in the path," symbols which were endings in lines characterized by small letters showing the proper way to read. The text is particularly intriguing in that frequent erasures seem to have been made of both drawings and script. Erasing, doodling in the margins (explicits) and corrections were a common practice.51

The final folio, The Temptation (see Fig. F, see p.22) is perhaps the most analyzed picture in the Book of Kells. Here we see the young Christ, his long curly golden hair tied at the top with a knot bun, surrounded by his followers and his angels, a look of fearful anticipation on their faces. The group on the left is reminiscent of the Greek chorus, offering prophetic advice to the hero as danger lurks around him. In this instance, danger lurks in the form of the black devil who is reaching as if to pull the youth toward him. In one of the most powerful examples of Christological imagery, Christ is seen as the leader of His community, the Augustinian city of men praying fervently that their master will make the right decision. The folio provides a temple motif as if Christ were sitting in His church with the strong blue pillars forming its structure, and the devil, withered and weak but still dangerous. The scene is dramatically described by St. Augustine as the struggle between the scourge of death and the light of life. He writes: "Christ the Emperor, battled the devil in the open so that humans could see him and learn from him."52

In the final analysis, the Book of Kells provides us with the power to see in its golden imagery the life of Christ, and in The Temptation His rise into heaven with His angels at His side. The Augustinian view of "the door, the last judgment, the tabernacle, and the ascension"53 are all on display in this remarkable picture, and together embody the Zeitgeist of insular illumination that gave the City of God it richness of visual culture and, as Gregory the Great said, gives us "a living reading of the Lord's story."54

The inspiration for the Book of Kells emanated from a love of God and the desire to know and remember all things holy. The Book of Kells lives today, testimony to the spirit of illumination developed 1500 years ago in the dark and damp cells of medieval monasteries. It lives in the present as a witness to the past.

Mr. Browning is a retired high school history teacher (31 years). His underÂgraduate and master's degrees are in American History. He taught Ancient and European History for many years at the college level in an adjunct role. He is presently an instructor in Western Civilization at the Community College of Rhode Island, and is pursuing his doctoral studies. He is married with three children.

1. Paul Johnson, A History of Christianity (New York: Atheneum Macmillan Publishing Co., 1976), 145.

2. William Winter, Old Shrines and Ivy (Boston: Joseph Knight Co., 1982) 107.

3. Encyclopaedia Britannica (Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., 1992) Vol. 6, 367.

4. Thomas Hannan, Iona: And Some Satellites (London: W. & R. Chambers Ltd., 1929) 70.

5. Rene Fulop-Miller, The Saints That Moved The World: Anthony, Augustine, Francis, Ignatius and Theresa (London: Thomas Y. Cromwell, 1945) 123

6. Ibid., 103

7. Ibid., 99

8. Bernard Meehan, The Book of Kells: An Illustrated Introduction to the Manuscript in Trinity College, Dublin (London: Thames And Hudson, 1984) 9.

9. Marc Drogin, Medieval Calligraphy: It's History and Technique (Toronto: General Publishing Co. Ltd., 1980) 26.

10. Ibid.,32.

11. Peter Brown, Book of Kells (London: Thames & Hudson, 1980) 18.

12. Fulop-Miller, 137

13. Brown, 19

14. Giovanni Papini, St. Augustine (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1930) 135.

15. Fulop-Miller, 120.

16. Augustine of Hippo, City of God. Translated by Henry Bettenson (London: Penguin Books, 1972) Book XIX, Chp. 14. 873-874.

17. Ibid., Book XI Chp. 21. 450.

18. Ibid., 436-437.

19. Augustine, Book XI, 436-437.

20. Ibid., Book XIX, Chp. 4, 857.

21. Ibid., Introduction XVI.

22. Ibid., Book XI, Chp. 34, 468.

23. Jean Leclercq, The Love of Learning and the Desire for God: A Study of Monastic Culture. Translated by Catharine Misrahi (New York: Fordham University Press, 1982)97, 17.

24. Ibid., 123.

25. Johnson, 144.

26. Hannon, 163.

27. Brown, 30-31.

28. Augustine, Book XI, Chp. 8, 437.

29. Janet Backhouse, The Illuminated Manuscript, (London: Phaidon Press Ltd., 1979) 8.

30. Bruce Robertson & Kathraan Hewitt, Marguerite Makes a Book (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1999)29.

31. Robertson - Hewitt, 30.

32. Johnson, 148.

33. Backhouse, 8.

34. Drogin, 86.

35. Dictionary of the Middle Ages, ed. Joseph R. Strayer, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1986)Vol8, 96 & 97.

36. Johnson, 155.

37. Leclercq, 122.

38. Ian Barbour, Religion and Science: Historical and Contemporary Issues (San Francisco: Harper & Collins, 1997)7.

39. David Harris, The Art of Calligraphy (New York, D. K. Publishing Book, 1995) 29.

40. Leclercq, 131,182.

41. Carol Farr, The Book of Kelts: It's Function and Audience (Toronto: The British Library and University of Toronto Press, 1997) 37, 144.

42. Meehan, 53.

43. Augustine, Book XVII, Chp. 20, 752.

44. Meehan, 80.

45. Meehan, 53.

46. Sister Wendy Beckett, The Story of Painting (London: Dorling Kindersley Books, 1994) 44.

47. Beckett, 44.

48. Meehan, 57.

49. Meehan, 78.

50. Harris, 29.

51. Drogin, 46.

52. Farr, 70.

53. Fair, 72.

54. Meehan, 29.

55. G. W. F. Hegel, Reason in History (Translated by Robert S. Hartman, New York: MacMillan, 1953), 95.