Christ the King

ANGELUS EDITION: Letter to Our Fellow Priests

The heart of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre's spirituality

is the doctrine of Christ the King.

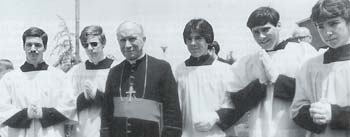

Archbishop Lefebvre celebrates Mass at Lou's Village Restaurant,

San Jose, California (May 7, 1983).

A superficial look at the work of Archbishop Lefebvre might lead one to believe that his main cause was the Mass. However, to restrict oneself to this aspect would mean failing to understand the real nature of the battles waged by the "iron bishop." Nothing but the dates alone points this out: well before the missal of Pope Paul VI was published, the Archbishop-Bishop Emeritus of Tulle told Archbishop Sigaud of his intention to "dedicate himself entirely to the fight against progressivism,"1 more particularly by founding an international seminary that he characterized as "traditional." [Archbishop Sigaud, a contemporary of Archbishop Lefebvre and an attendant at the Second Vatican Council, was a key member of the conservative group of bishops at Vatican II, the Coetus Internationalis Patrum. He was Archbishop of Diamantina, Brazil (1960-81).–Ed.]

From the outset, Archbishop Lefebvre often explained the grounds for his determined opposition to the new spirit that had for years been infiltrating the Church and had officially prevailed on the occasion of the Second Vatican Council: the current of doctrinal liberalism which undermines the fundamental attitude that man must have towards God. Thus it affected the very heart of religion even before rubbing off on its teaching and liturgy. By opening the Church up to "the best values of two centuries of liberal culture," to employ Cardinal Ratzinger's language, the churchmen compromise the fundamental attitude of dependence which man must have towards God. As paradoxical as it may first seem, the fundamental spirituality of the "rebel bishop" was one of dependence: the dependence of the creature upon its Creator, the dependence of sinful man upon his unique Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ. It was insofar as the modern errors cast doubt upon this principle of dependence that Marcel Lefebvre, as bishop, deemed it incumbent upon himself to express in union with the popes his opposition to them in order to defend God and His rights.

This explains the deepest motive which alone can account for 30 years of dolorous battle waged by the most Roman of bishops: "The fundamental, essential idea of the convinced Catholic, but also simply of a wise man, is the reality of our dependence on God and the need to live accordingly. We must always come back to this fundamental, essential principle in the light of faith," he was to say to his priests.2 This was the principle which governed his attitude from the earliest clashes. As a member of the Council's Central Preparatory Commission, he criticized the definition of liturgy put forward in the schema for being "incomplete, because it affirms more the sacramental, sanctifying aspect and not enough the aspect of prayer. But the fundamental purpose of liturgy is to worship God, an act of religion."

It was by frequentation of the first truths enunciated by the Faith as well as by sound philosophy that Archbishop Lefebvre sustained this spirit of dependence. For even theodicy, [the knowledge of God attainable by reason alone], teaches that man is a being ab alio–by another–while God alone is ens a se. At the deepest level, man is defined by dependence and can only truly live as a man in the measure that he recognizes and lives according to this dependence. As he wrote in his Spiritual Journey [available from Angelus Press. Price: $7.95], his final testament:

The deeper one looks into this reality, the more one is stupefied at the all-powerful nature of God and at our own nothingness, at the necessity for each creature of being constantly sustained in his existence, under pain of ceasing to exist, of returning to nothing....Nothing but this meditation, and this realization, should plunge us into humility and profound adoration and establish us immutably in this attitude like to the unchanging God Himself.3

The thrust of the idea behind these lines shows it sufficiently: we are not dealing with the God of the philosophers, however unique he may be, but we are rather in the presence of our Lord Jesus Christ, true God, who claimed for Himself the divine name (Ex. 3:13), ens a se: "Before Abraham was, I am" (Jn. 8:58).

Archbishop Lefebvre's deep faith constantly reminded him of another equally fundamental aspect of this dependence: because he is born a sinner, because even after baptism he bears within himself the "fomes peccati [propensity to sin], man is in a state of radical dependence on our Lord Jesus Christ for everything that concerns his salvation.

Even after baptism, I remain an invalid; I am blind [the wound of ignorance]; I am tempted to not render to God and to my neighbor what I owe them [malice], I am weak; and I am tempted by the things of the world [concupiscence]: these are the four great maladies about which St. Thomas Aquinas speaks, which form this fomes peccati, this tendency to sin that we all have even after baptism. We must never forget it; we must preach to the people: "You are sick." And so we need a doctor, we need constantly to be redeemed by the blood of our Lord Jesus Christ. The hour of Redemption has not ended for us personally; it continues.4

The matter is clear. Recalling the sentence of Jeremias: "Cursed be the man that trusteth in man" (Jer. 17:5), Archbishop Lefebvre was not one of those who think that man can find within himself, by an effort of consciousness raising, the way of salvation. For him salvation is in no other than our Lord Jesus Christ:

Our mind is sanctified in the truth which is taught it, which does not come from it. Our will is sanctified in the law and the grace of the Lord, which do not come from it....Our spirituality is objective in this sense that everything which sanctifies us comes from God by our Lord. "Without Me," says our Lord, "you can do nothing" (Jn. 15:5).5

Consequently the untiring labor of the missionary he was had no other goal than to bring our Lord to souls in order to subject all to our Lord. Because everything was made "by Him and for Him" (Col. 1: 16), individuals, families, and societies, everything must be brought back to our Lord Jesus Christ. Archbishop Lefebvre's spirituality was none other than the spirituality of Christ the King. In keeping with the patristic tradition, he understood his missionary task as the imperious need to gather all men to this dependence on Christ so that they might adore the Lord God and serve Him alone.6 Archbishop Lefebvre liked to quote the words of the popes, especially those of Pius XI in his encyclical Quas Primas:

...Nor is there any difference in this matter between the individual and the family or the State; for all men, whether individually or collectively, are under the dominion of Christ. In Him is the salvation of the individual, in Him is the salvation of society. "Neither is there salvation in any other, for there is no other name under heaven given to men whereby we must be saved" (Acts 4:12). He is the author of happiness and true prosperity for every man and for every nation.

The man who had seen slowly develop Christian communities in black Africa could testify to how this dependence on God, again made possible by the redeeming cross, characterizes Christian civilization:

Christianity is the society living in the shadow of the Cross....Christendom consists of this village, of those villages, cities, and countries which, following Christ on the cross, accomplish the law of love under the influence of the Christian life of grace.7

When man's viewpoint is deeply anchored in the elementary truths of our Catholic Faith, he is able to perceive in counterpoint the malice of a spirit that seeks to free itself from dependence on God: a Satanic malice, since it adopts Lucifer's "non serviam." Formed by holy teachers at the French Seminary in Rome, the young Marcel Lefebvre made his own the view of St. Augustine on mankind's history: it can only be a combat, since to each generation and every man the Evil One tries to impart his spirit of independence, of the exaltation of man at the expense of man's rightful dependence on God. He wrote:

Fr. Le Floch made us understand and relive the Church's history and the combat which perverse forces have waged against our Lord....That mobilized us against the powers of evil working to overthrow the Church, the reign of our Lord, Catholic states, the whole of Christendom.

These Satanic forces at work no one then hesitated to denounce; quite the contrary. The enemy was clearly identified in order the better to defend against it. In the shadow of the Holy See, enlightened by numerous papal encyclicals, the young Lefebvre learned for good how to recognize it: Freemasonry issued from the Protestant revolt, laicism inherited from the French Revolution; Communism, characterized as "intrinsically perverse"-all were so many attacks directed by Satan to uncrown the Lord. With such an enemy no pact is possible because the antagonism is seated at the level of principles. Logically, according to the logic of mercy which seeks the salutary reversal of the sinner, the Freemason was excommunicated, laicism was condemned, and false religions were denounced as such.

The drama of Archbishop Lefebvre was not in this combat, inherent as it is in the Church's condition here below, as is recognized in her title of Church Militant. His great sorrow was to see those in power in the Church compromise with the enemies of the reign of our Lord even though this "liberal temptation" had been condemned many times by the popes of the 19th and 20th centuries. This compromise was at issue in the Council, and consequently was the cause of Archbishop Lefebvre's reaction then, as is evidenced by his intervention regarding the Constitution on the Church and the Modern World, Gaudium et Spes.

The pastoral doctrine presented therein is not in accord with the doctrine of pastoral theology taught by the Church up to the present. And this is true: whether it be on the question of man and his condition or that concerning the world and societies or the family and secular life, or again on the subject of the Church herself, the doctrine of this Constitution is a new one in the Church....

...For instance: the Church has always taught, and continues to teach, the obligation for all men to obey God and the authorities established by God, in order that they may return to the fundamental order of their calling and thus recover their lost dignity.

The schema, on the contrary, says: "Man's dignity is in his freedom of conscience, in his personal actions guided and moved from within himself, that is, of his own volition and not under the compulsion of some external cause or by constraint."

This false notion of liberty and of man's dignity leads to the very worst consequences....

This pastoral Constitution is not pastoral, nor does it emanate from the Catholic Church. It does not feed Christian men with the Apostolic truth of the Gospels, and, moreover, the Church has never spoken in this manner. We cannot listen to this voice, because it is not the voice of the Bride of Christ. This voice is not that of the spirit of Christ. The voice of Christ, our Shepherd, we know. This voice we do not know. The clothing is that of the sheep. The voice is not the voice of the shepherd, but perhaps that of the wolf.8

We can see that at the center of this compromise–betrayal, the Archbishop called it–is the teaching on religious liberty understood as independence regarding the means willed by God for our salvation. Such a compromise was impossible for the man of faith who was Archbishop Lefebvre, and he could only firmly resist such attempts:

We who desire to save and re-establish this dependence on God and on our Lord Jesus Christ through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary, well, we revolt against those who do not want dependence on God, dependence on our Lord; we revolt against those who would ruin all dependence on our Lord Jesus Christ.9

The 40 years that have passed since the Council tell the story: Archbishop Lefebvre's reaction was not the work of a desperate schismatic, but rather that of a pastor who constantly sought to submit all things to Jesus Christ. And his means:

What is the act of the Church which really places us in our relationship of dependence on God, on our Lord Jesus Christ? It is the holy sacrifice of the Mass. There is the heart of the Church, there is the most beautiful, the deepest, the most real expression of our dependence on God. When we genuflect before the cross, when we genuflect before the holy Eucharist, we profess our dependence on God.10

This is the reason for his work in favor of the Catholic priesthood, because the restoration of all things in Christ "could not be realized without the priesthood, whose particular grace is to perpetuate the unique Sacrifice of Calvary, source of life, of redemption, of sanctification, and of glorification. The radiance of priestly grace is the radiance of the Cross."11 Therein is contained the whole program of the Society founded by him.

Translated exclusively for Angelus Press from Letter to Our Fellow Priests, No. 16, Dec. 2002. Fr. de la Rocque is a professor at the Society's St. Cure of Ars Seminary, Flavigny, France.

1. Letter of Feb. 2, 1967.

2. Conference, Dec. 13, 1984.

3. Spiritual Journey, p. 4.

4. Conference, Dec. 13, 1984.

5. Spiritual Journey, p. 70.

6. Cf. Origen, hom. 30 in Lucam.

7. Spiritual Journey, p. 45.

8. I Accuse the Council (Angelus Press, 1982), pp.75-80 passim.

9. Conference, Dec. 13, 1984.

10. Cor Unum, no. 20.

11. Spiritual Journey, p. 45.