Liturgiam Authenticam

A Study of the Document Liturgiam Authenticam on

the English Translation of the Novus Ordo Missae

Rev. Stephen Somerville

The Angelus hears again from the priest who helped "translate" the New Mass. (See The Angelus,Oct. 2002.) His first-hand account of his service on the International Committee on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) is invaluable. His further commentary on Liturgiam Authenticam convinces one that to change the Latin Mass at all was ill-advised. Why change what wasn't broken?

|

Reverend Fathers,

It is an honor and a pleasure for me to receive this invitation to come and speak to you about the holy Catholic liturgy, and to get to know your Confraternity at least modestly during these four days of your 2002 convocation.

It was Fr. John Trigilio, your Vice-President, who conveyed to me most courteously that invitation, and the travel arrangements to this famed Shrine of the Blessed Sacrament. It may be that my name was raised by your President, Fr. Robert Levis of Gannon University in Erie, PA, whom I remember hearing and reading and meeting close to 1966 in Erie. By that time, I had been ordained a priest for ten years and I answered an invitation from the Benedictine Sisters of Erie to conduct a weekend workshop on Liturgy at their convent. I recall that it was Christ the King Sunday, on the old date in October [according to the 1962 Calendar–Ed.].

More pertinently to the present occasion, people had come to know that since before my Erie visit, specifically since 1964, I had been serving as one of the original team of the ICEL Advisory Committee, ICEL being the International Commission on English in the Liturgy [see The Angelus, "Renouncing My Service on ICEL," Oct. 2002–Ed]. You know that this multi-nation body of anglophone bishops was to be responsible for translating the new Latin liturgy [of the new Mass—Ed.] into English. The priest-secretary they chose for their task was a young priest from Erie, PA, Fr. Gerald Sigler, who had done, as I recall, some further studies in Canon Law. Fr. Frederick McManus, canonist from Catholic University of America, was also one of the first on the ICEL roster. There were three men from England—one a priest and another a naturalized American. Being then the youngest of the crew, I can assure you that the survivors today are certainly senior citizens—only Fr. McManus and myself.

Fr. Trigilio alluded to the fact of controversy over recent proposed ICEL translations, and hoped that I might share with you any helpful ICEL experience to understand better the liturgical scene. This I will strive to do.

First, a smidgen of personal history. In 1963, I was named to teach music at St. Michael's Cathedral Choir School in Toronto, Canada, the alma mater where I had acquired my basic boyhood music training as chorister, pianist and organist, and choir conductor. In 1963, Vatican II was flaming into its second year and liturgical change was in the air, especially translation into English. One of the pop concerns at the time was over the Gloria in excelsis Deo. How do you translate, " Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis; qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram; qui sedes ad dexter am Patris, miserere nobis"? Do you say, "Thou who takest away the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Thou who takest away the sins of the world, receive our prayer. Thou who sittest at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us?"—Yes, this is manifestly the correct translation. But since the revolutionary '60's, the progress tigers have been chafing at the leash, and "Thou-Thee-Thy" were marked for destruction and banishment to grandma's old prayer book. "Impossibly archaic!... Intolerably fusty!" The right word for today, they said, was "you"! "You take away,... You sit at the right hand..." and so forth. But wait! The Latin is "qui tollis,...qui sedes." We were made to say, "You who take away.... You who take away.... You who sit...." Well, the wags soon saw that the new Roman Catholic liturgy would come to be nicknamed the uYoohoo Mass." And indeed, for a time starting in 1964, this "you-who-take-away" construction was an official interim version.

Whatever the case, some impulse prompted me to assert my ecclesial awareness and write a letter to the Canadian bishop responsible for liturgy, on the perils of translating the Gloria in excelsis Deo. A few weeks later, I was appointed a member of the ICEL Advisory Committee.

|

|

|

Was I pleased and excited by this election to ICEL? Yes, I was, in a confused way. Was I complacent or boastful or proud? Far from it! I was uncomfortably aware of my lack of competence and scholarship to be truly equal to the task. I knew at least two or three Canadian priest names who were more fit for the post than I. But this anxiety was soon overwhelmed by the flurry of translation activity into which we were plunged by a busy and efficient secretariat in Washington, D.C., guided by Frs. Sigler and McManus. These in turn were stimulated by that rising Roman star, Rev. Fr. Annibale Bugnini, later Monsignor, later Arcivescovo, also known secretly as "Buan," we are told, to his Freemason brothers, and later frequent traveler to Iran. Fr. Bugnini was pushing rapidly to produce the Novus Ordo Missae (which has reminded some observers of the Masonic Novus Ordo Saeclorum on the back of a well-known dollar bill). I remember the occasional lecture on liturgy by Fr. Bugnini in 1956 when I was briefly a student of sacred music in Rome and learning Italian.

It is widely known today that ICEL's translation of the Liturgy has occasioned much criticism and controversy. Was this always the case from 1964 onward? Was ICEL criticized from the start?

I have carefully preserved all my correspondence from and to ICEL, stretching from 1964 to the present. There is a gradual reduction of volume in the 1980's as I became stronger in my criticism of its work. An early and significant piece of controversy arose in late 1967, concerning ICEL's draft version of the Roman Canon, that is, Eucharistic Prayer I. In London, The Tablet Catholic newspaper of 18 November of that year carried a criticism of the ICEL draft by one of our very own members, Prof. Herbert Finberg, a gifted literary man and translator, a conservative, who had specialized in local English history. Other persons joined in the debate in subsequent issues, agreeing and disagreeing, and including our Chairman, Fr. Harold Winstone, a London parish priest and competent translator. Because of Finberg's appeal to the public over our heads, his unrelenting stance and other factors, the ICEL Secretary, Fr. Sigler, proposed to us members that he be asked to resign, on the grounds of his "inability to cooperate" with the Committee.

Did Prof. Finberg resign? No, not till many years later. He had a powerful friend on the episcopal committee who probably saved him. To this, I say "rightly so," because Prof. Finberg stood for Catholic tradition, for a dignified style, and for verbal fidelity to the Latin. I give one detail as an example: Members of ICEL were wanting to drop the title "Mother of God" for Our Lady in the Canon. Finberg defended and demanded it. Of course he was right, and was later vindicated by higher authority. The ICEL Roman Canon, for all its faults, still says "Mother of God."

Where did this author stand in all the discussion? I confess that I was then a confused novice, still lacking parts of that firm foundation needed by every Catholic liturgy leader. I was truly perplexed, and ready to bend anxiously toward the latest opinion being heard. I remember, to my shame, being persuaded reluctantly to vote at ICEL for "And also with you" instead of the faithful and more meaningful "And with thy spirit." Do Catholics still know they have a soul? Perhaps you have heard the story of the priest who some years later was invited to celebrate Mass in a church with which he was unfamiliar. He began by saying, "There's something wrong with this microphone," and the people responded, "And also with you!"

Amidst all this unfolding of ICEL life, I had already been an occasional translator. I was asked to render the Collect prayers for the interim Canadian edition of the new Holy Week liturgies. In so doing, I translated every word and expression, not slavishly, but as exactly and faithfully as possible. Here it shows that there was a meeting of minds between Prof. Finberg and myself. But I must repent of several ICEL moments—which I recall—when I yielded to some brief movement of disdain, or, worse, of ridicule for this wise, faithful, forgiving, and patient Catholic gentleman....

Did ICEL, after the 1967 arguments over the Canon, move closer to tradition, or rather, to creativity? To fidelity, or to freedom? To constancy, or to progress? The ICEL trend was definitely not to the Right, but to the Left, not to conserve, but to change. This was the direction, as we know, of the Second Vatican Council, recently concluded. It was also the public and media mood of that revolutionary decade, the 1960's.

Let me illustrate ICEL's movement by her own official guidelines. From the beginning, ICEL drew up a set of ten "First Principles" for liturgical translation. They were unanimously agreed to by the members. They were very conservative and traditional-sounding. I remember objecting at the meeting to the abstract sound of "First Principles." I suggested instead the title, "Guideposts." And Fr. Sigler, our very progressive Secretary, promptly counter-suggested "Guidelines" because, as he said plainly, "A post sounds rather static, but a line is moving, is going somewhere."

|

|

|

I remember that except for Prof. Finberg on occasion, we hardly ever invoked these "Guidelines" which tended to favor traditional English expressions of devotion and prayer books. Perhaps we knew instinctively that they were chiefly window-dressing to allay the conservative fears of senior Catholic bishops and priests and laity. Probably the progressive members intended to ignore them and bring forward, inch by inch, the new language to be imposed on Catholic worship. Whatever the case, they became rather irrelevant in 1969 when the Vatican issued an Instruction (in French) precisely on the translation of liturgical texts. This document, titled by its opening words Comme le prévoit (meaning "as foreseen") was drafted, not by the conservative Sacred Congregation of Rites, and not in Latin, but by a new Vatican body called the Consilium. This powerful committee was created in 1964 by Pope Paul VI precisely to implement the reform of the Liturgy called for in the Vatican II Constitution on the Liturgy and to counterbalance the cautious procedure of more traditional-minded Vatican bodies. Secretary Bugnini took full advantage of these five years, 1964-69, but the group was abolished in 1969 and its president, Cardinal Lercaro, was dismissed. It was replaced by the former Congregation of Rites, now re-named Congregation of Divine Worship, but Archbishop Bugnini remained in charge until his disgrace in 1974.

Comme le prévoit was promptly translated into English by ICEL. In French, it had been a fairly sensible, only moderately progressive document. In English, however, the hands of the ICEL secretariat had subtly altered many expressions, opening them up, dishonestly, I may say, to greater radicality.

To explain these remarks, allow me to leap forward to 1986 when ICEL published a Redbook for revising the translation of the New Order of Mass. Conscious then of years of serious criticism of its work, ICEL was trying to remain progressive yet show a face of serious improvement. The secretary was then Mr. John Page. He still holds this office in 2002. Fr. Sigler and successor Fr. John Shea had both resigned and later left the priesthood. Mr. Ralph Keiffer then served somewhat briefly, and was succeeded by the Augustinian, Fr. John Rotelle. Getting back to that Redbook for Revision in 1986, we see that it contains nine guidelines for translators. The first five of these are said to be based on Comme le prévoit. Let me say plainly that all nine guidelines reveal a bias, a bias which leans away from verbal or literal fidelity, a bias towards liberty and novelty, towards change in the wording of liturgical prayers. To save time and your good patience, let us look only at the second guideline of the Redbook. Guideline Two begins:

It is not sufficient that a liturgical translation merely reproduce the expressions and ideas of the original text. Rather it must faithfully communicate to a given people, and in their own language, that which the Church, by means of this given text, originally intended to communicate to another people in another time. A faithful translation, therefore, cannot be judged on the basis of individual words: the total context of this specific act of communication must be kept in mind as well as the literary form proper to the respective language (Comme le prévoit, English Translation, §6).

End of guideline. Does it not sound like the jargon, the mumbo-jumbo, of a linguistic expert? How does the Church convey to us her intention if not by the expressions she uses? Which is more important: for the Church's liturgy to speak in the language of every people and parish and gathering, or for the people to learn to recognize the voice and language of the Church? "The sheep," says Our Lord, "follow [the shepherd], because they know his voice. But a stranger they follow not, but fly from him, because they know not the voice of strangers" (Jn. 10:4-5). Is ICEL here confusing the homily, the announcements, the local prayer intentions, and pastoral conversations with the official liturgical text? How can one ICEL translation speak the language of every group at once?

Since when did Vatican II intend the new Latin liturgical books "for another people in another time?" Indeed the Council intends them for the Church today. And furthermore, is the Church of the past and of the present two Churches, two peoples? Is she not "One?" Is the Church's historical unity not relevant to her liturgy?

What precisely is the "total context of this specific act of communication?" The answer surely is inexpressibly and infinitely manifold, being the myriad contexts of a worldwide church of hundreds of millions. The local pastor and deacon and catechist and hospital visitor know this best of all. But such a concept of context can never be a specific, realistic guide for a translator of the Roman liturgy.

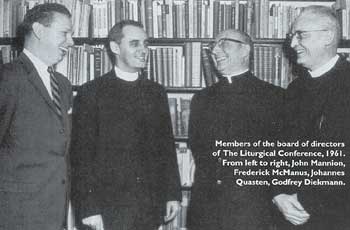

Members of the board of directors of the Liturgical Conference, 1961.

From left to right, John Mannion, Frederick McManus, Johannes Quasten, Godfrey Diekmann.

I have commented elsewhere that every time ICEL had occasion to quote Comme le prévoit, it described it as an "instruction of the Holy See," that is, not an instruction of Rome, or the Vatican, or the Consilium, but of the "Holy See." ICEL seemed to feel the need of bolstering its position by invoking "holiness" around a low-level Vatican document that had been mistranslated, deliberately and mischievously, in ICEL backrooms. I have no recollection that our ICEL Advisory Committee ever critically discussed the English translation of Comme le prévoit. It just appeared, like Melchisedek! It certainly should have been debated by us before appearing. I remember, early in the ICEL history, a resolution we passed that our Advisory Committee would be responsible for choosing translators. I have no memory of our ever doing so, except in some of our earliest work on the lectionary refrains and the four Eucharistic Prayers. In those first few years, it was understood that we advisors would contribute to the actual translating. Before long, however, it became an unwritten rule that members of the Advisory Committee would not do any actual translating, and this "on principle," we were told. On what "principle?" It was never stated, but I sense in hindsight that it was concentration of power in the Washington Secretariat. There, the five Executive Secretaries came and went. One person never went. He was the aforementioned Fr. Frederick McManus, the permanent Treasurer until about 1998, long after I had I departed ICEL. I recently read a new critique of ICEL by a meticulous theologian-canonist priest of New Zealand who studied theology and law in the Vatican. He left the reader to understand that the principal controller of ICEL translation policy was the controller of its purse strings, i.e., Fr. McManus. He calls him "the liturgical puppet master of the entire English-speaking world."

Was the Vatican authority beginning to share the mentality of criticism for ICEL's insinuation of change into the Liturgy? In April 1996, the Congregation of Divine Worship received from the National Council of Catholic Bishops [NCCB] the ICEL draft for the rite of Ordination. Six months later, the Cardinal Prefect wrote back to the president bishop of the NCCB with a 13-page list of 114 specific flaws that "cannot be considered in any way exhaustive." He recommended "a complete change of translators...and a new version be made afresh...." The Vatican seems now to be demanding professional and faithful standards of translation.

Liturgiam Authenticam [hereafter referred to as LA–Ed.] is a 51-page document on the translation into vernacular languages of the Roman Liturgy. It is a practical treatise on translation. It is the fifth and latest major Instruction since 1964 from the Vatican on the right implementation of that renewed Liturgy which was called for by the Second Vatican Council in December 1963. Liturgiam Authenticam is detailed, demanding, and designed to do away with much disorder and confusion in our post-conciliar churches. Because of the poor translations that have prevailed, we must acknowledge that LA fills a long-standing need.

Here is a thumbnail sketch of the document: It begins with a three-page "background." A seven-page "overview" follows. These seven pages are a good summary of the whole Instruction. Page 10 begins the Instruction proper, up to page 44. These 35 pages are divided into 5 chapters with 133 numbered paragraphs. Part II, regarding translation proper, is the longest with 14 pages and 51 paragraphs. The last 7 pages of LA are endnotes. Enough of the structural data; let's plunge into this document at §1. We read that

the...Council strongly desired to preserve...the authentic Liturgy [flowing from] the Church's...ancient spiritual tradition and to adapt it ... to the genius of the various peoples...[emphasis mine].

Notice the two verbs, to "preserve" the Liturgy and to "adapt" it. Notice the adjective "authentic" modifying "Liturgy." These last two words have been chosen for the suggestive title of the whole document, that is, they come first of all the words in the Latin opening sentence–Liturgiam authenticam. The Vatican is rightly anxious to reassure faithful Catholics, to underline authenticity, or genuine Catholicity, in our worship. Many today deplore what has happened to the Roman Liturgy. "Authentic," they would deny; "adapted," yes, but badly; "preserved," hardly at all. One author has calculated that the Novus Ordo is 60-80 percent new material over the old Ordo Missae.

The second paragraph states candidly that the renewal of the Roman liturgical books would include their translating into vernacular languages. This in turn would be in view of a renewal of the liturgy itself, called a "foremost intention of the Council." There is some confusion or a violation of language here. To renew the liturgy books is virtually the same as to renew the liturgy... But the renewal of the Liturgy turned out in fact to be a revolution. And it is clear that the [majority of] bishops at Vatican II were not clamoring for a radically new liturgy...

The third paragraph of LA blandly states that the renewal "has seen positive results," with particular thanks to "the bishops." This sounds rather like damning with faint praise. Many critics of the Catholic scene would agree...

Paragraph Four gives honor to the Eastern Churches. Vatican II, we are told, recognized the tradition, discipline, and liturgy of the ancient Oriental Churches, and wanted these to remain "whole and intact," since they manifest the faith of the Fathers and the Apostles. LA tells us that Vatican II said these things "even while calling for the revision of the [Roman] rites." LA sounds uncomfortable here. It is saying, "Dear Oriental Catholics, we Romans are changing our liturgy, but don't you change yours!" LA continues by saying it is a Vatican II principle to change the liturgy only in ways "which would foster the specific organic development of the rites." These words are not very clear to me. I think they try to echo the Vatican II teaching that any liturgical changes must be clearly needful and must derive organically from existing rites. LA goes on to demand "vigilant safeguarding" and also "authentic development" of liturgy, tradition, and discipline in the Roman rite. Translation of it will demand the "same care." Finally, the Roman Missal must "continue to be maintained as an outstanding sign and instrument of the integrity and unity of the Roman Rite." All of this is so very true. And all of this has in fact been neglected by...Vatican offices, liturgists, bishops, by ICEL, and by parish priests.

In the fifth paragraph, LA praises the absorbent and universal qualities of the Roman Rite, calls for its "unitary expression," and says all adaptation and inculturation must not produce new varieties or families of rites, but remain part of the one Roman Rite. I suspect these earnest and hopeful words veil an anxiety over the present day fragmentation of the Church which the Vatican and its frail Holy Father are increasingly powerless to moderate or redirect.

Paragraph Six says diplomatically that existing translations of the liturgy need improvement or actual rewriting. I suspect that the ICEL's English translation needs this re-writing most of all the languages. This, by the way, is already in process. LA very truly observes that poor translations impede the desirable inculturation and consequent renewal of the Church. This is so because "Lex orandi, lex credendi" that is, "The way we pray determines the way we believe." If we pray with poor translations, we end up with poor belief.

Paragraph Seven now says frankly that LA will give "the principles of translation" for all future undertakings and will illustrate these with "tendencies"–a diplomatic word for errors–that have arisen. I remark that every such illustration I have noted in LA was to be found in the ICEL versions. LA seeks, we are now told, "a new era of liturgical renewal."

We need to bear in mind that all the new and changed things in our liturgy, particularly the texts, were approved and confirmed, first by the bishops, and then by the Vatican authority. These translations by ICEL were to many minds clearly deficient and unfaithful. They should never have been approved. The fault is not entirely with ICEL.

We have just seen the first seven of the introductory paragraphs of LA. Let us glance briefly at the two remaining.

Paragraph Eight tells us that LA supersedes all previous Vatican norms on translation and inculturation, except the fourth instruction which is on inculturation titled, Varietates Legitimae, and given in January 1994. This and LA are now joint instructions. Will there be more? Yes.

Paragraph Nine tells us that a future document, called a "ratio translationi" ("concept of translation"), will be carefully prepared with the help of bishops to apply the principles of LA in closer detail to a given language. This may entail a list of vernacular words to be equated with their Latin counterparts for that specific language. Such a practical help suggests the Vatican is truly serious about promoting ongoing serious improvement of the vernacular liturgy.

Part I In General

Part I of LA now begins concerning the choice of vernacular languages into which to translate. Not all languages will be permitted such as dialects that are not used in pastoral communication. The danger is noted that vernacular languages can fragment the faithful into small groups, and later could foment civil discord and endanger the unity of the particular churches with the Church universal....

Part II In General

Part II deals with actual translation. Part II is the heart of LA. It is the most practically beneficial and necessary part. It has four sections, which I shall briefly note. Section One of Part II is on general principles for all translation. Section Two gives norms for Scripture and Lectionary texts. Section Three covers other texts, and treats of vocabulary, syntax, style and literary genre. Section Four is norms for special texts, e.g., the Eucharistic Prayers and the Creed, and the praenotanda for a given liturgical book, e.g., infant baptism. It is usually called in English the General Instruction.

Part II, Section One: General Principles

Let us now look at Section One of Part II: "General Principles." Cardinal Ratzinger is reported to have said in his 1977 autobiography that the revolutionary arrival of the New Mass made many Catholics think that the liturgy is not something given but is to be created by each community. This romantic, nonsensical notion is reflected in the ICEL guidelines of 1986. You have probably all heard it here and there in the post-Vatican II past. LA teaches, "Translation of the Roman liturgy is not so much a work of creative innovation as it is of rendering the original texts faithfully and accurately" (§20) [emphasis mine].

Now this is true and good to hear. But I ask you, why does LA say translation "is not so much a work of creative innovation"? Is it not because the new post-Vatican II liturgy–the Novus Ordo–is, precisely in its Latin original, a huge work of "creative innovation"? Is it not a striking departure from the worship of our fathers? Is it not a drastic change in lex orandi? And, if so, such innovation must not be too roundly condemned in LA, or the same stick will be used to beat the Latin liturgical authority.

At any rate, LA goes on to say: translate integrally, most exactly, neither omitting nor adding anything, and without paraphrases or glosses. Such was the way our pre-Vatican II English-Latin people's missals were translated.

I summarize the successive paragraphs briefly:

(§21): Speaks of peoples newly-come to the Catholic Faith and lacking ready words in their language for rendering some traditional Christian concepts.

(§22): Considers radical changes proposed for future liturgies. These must be based on true, documented necessity, not a mere desire for novelty, or seeking to change or supplement the theological content of the Latin.

(§23): Translate the typical edition from its Latin, not from some other Latin, and to consider retaining the occasional Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic words, such as Alleluia, Amen, Kyrie eleison, Agios o Theos, Talitha kum, and so forth.

(§24): One may not translate from another translation, but only directly from the original. This means Latin for the Church texts, and Greek or Hebrew for the Scriptures, with reference for these latter to the Neo-Vulgate Latin Bible, to assure consistent Catholic interpretation. (It seems to me that some smaller language groups will lack scholars to achieve fully these instructions.)

(§25): Avoid "servile adherence to prevailing modes of expression," and "contribute to the gradual development of a sacred style that will come to be recognized as proper to liturgical language." Avoid the temptation to "sanitize seemingly inelegant expressions" in Scripture. All these principles should "free the liturgy from the necessity of frequent revisions."

(§28): Avoid adding explanations. Let what is implicit remain so. Avoid heavy-handed explicitness. Include some Latin texts in the vernacular edition "especially those from the priceless treasury of Gregorian Chant... [which should] be given pride of place."

(§29): Reminds the homilist and the catechist of their task to explain the meaning of the liturgy, and the Church's understanding of Prostestants, Jews, and others, without unjust discrimination, and without altering any scriptural or liturgical text. (I take it this means we may not change "the Jews" to "the Authorities" when the New Testament happens to use "the Jews" in some negative context.)

(§§30-31): The question of feminist language is handled here. LA does not use the word "feminist," and uses "inclusive" only once in inverted commas to show that it does not recognize the word. Neither do I. I call it "feminist language," or sometimes "gender-neutral language." To change masculine words that denote both men and women is not "an authentic development of the language." To make such change in a liturgical text may mean detriment to its 1) meaning; to the 2) correlation of various words (e.g., the rich antithesis between "God" and "Man"); and to 3) aesthetics. I refrain from citing further examples. LA cites the use of Adam (Hebrew) or Anthropos (Greek) or homo (Latin), all meaning inclusive "man," which is to be "maintained in the translation." LA then defends the Church against "externally imposed linguistic norms that are detrimental to [her] mission." Feminist language is clearly envisaged here.

Paragraph 31 gives specific rules. Avoid "mechanical substitution of words, transition from singular to plural, splitting a collective term into masculine and feminine parts, and the introduction of impersonal or abstract words." These all may "impede the true sense" of the liturgical text, and cause "theological and anthropological problems." The following particular rules are given:

1) Maintain the established gender usage for God and the Persons of the Holy Trinity.

2) Maintain the fixed expression "Son of Man."

3) Maintain the expression "the Fathers" when it refers to the patriarchs or kings in the Old Testament or to the "Fathers of the Church." I do not know why LA seems here to omit the case of "our ancestors" or "forefathers," as in "Our fathers did eat manna in the desert" (Jn. 6:31).

4) Maintain "she," not "it," when referring to the Catholic Church.

5) Maintain "brother," "sister," etc. when these are clearly masculine or feminine by virtue of the context. (This to me is not clear. Shall we continue to say, "If your brother sins against you?" I think so.)

6) Maintain the gender of angels, demons, gods and goddesses.

(§32): Respect and maintain the sensus plenior [the fuller meaning] and not restrict it. Surely this means for example to translate "The God of Peace" and not "The God who gives us peace," or some similar expansion.

(§33): Maintain the capitalization that is in the Latin.

Part II, Section Two: Norms For Sacred Scripture And The Lectionary

In Section Two of Part II we are given the norms for Scripture and for Lectionary. LA says the Bible for the Catholic liturgy must be exegetically sound, of good literary quality, and suitable in style and language (§34). If such does not exist, a suitably modified existing version may be used (§35). The liturgical Bible should be uniform and stable in a given territory, so that the people are helped to memorize it, at least the important passages. This stability is especially desired in the psalms, which constitute "the fundamental prayer book for the Christian people." If such a complete Bible does not yet exist, it should be commissioned and published (§35). I would like to remark that such a good Catholic Bible does exist and was in fact used throughout the English-speaking world until the 1940's. I remember it clearly from my childhood Sunday Masses and Sunday Missals. It is the Douai-Rheims Bible, named after the two French cities whither the English Catholic Bible scholars had taken refuge during the Elizabethan persecution in England. It was revised in 1750 by Bishop Richard Challoner for greater clarity. Its publisher, Thomas A. Nelson, has persuaded me by his Preface to this Bible and by his striking little book Which Bible Should You Read? [Rockford, IL: TAN Books and Publishers, 2001. To order call 800-437-5876] that the Douai-Rheims is the most faithful and exact English Catholic Bible in existence and should become once again the Bible for the Catholic Liturgy. It is amazingly close to the Latin Vulgate, which in turn is rigorously faithful to the Ancient Hebrew and Greek manuscripts still extant in St. Jerome's time. The only retouching required in Douai-Rheims is to incorporate the conservative emendations made in the Neo-Vulgate of 1986 and to correct the occasional obsolete expression or usage. Archaic expressions are not obsolete expressions and, if more faithful, they should be retained. This includes, of course, "Thou," "Thee," and "Thy." Spoken English has for long been impoverished by the loss of the second person singular pronouns. But the inspired Scriptures use them, by God's will. In their translation, we should do likewise. Blanket use of "you" causes loss of meaning! Consider this passage:

And the Lord said: Simon, Simon, behold Satan hath desired to have you [plural, referring to all twelve Apostles], that he may sift you as wheat: But I have prayed for thee (singular, Peter alone), that thy faith fail not: and thou, being once converted, confirm thy brethren" (Lk. 22:31,32) [emphasis added].

How misleading to say "you" and "your" for Peter when this would seem to give to all the Apostles the grace of firm faith, conversion, and confirming here given by Christ uniquely to Peter!

Returning to LA, we read that the Catholic Bibles must conform to the Neo-Vulgate Bible, but in a rather vague way (§37). The Vulgate is said to be "the point of reference as regards the delineation of the text." What precisely does this mean? The Catholic versions must also "follow the same manuscript tradition as the Neo-Vulgate." It would require a serious bible scholar to do that! Next, LA demands "conformity with the Latin liturgical text" of the given passage (§37). What exactly is this "conformity?" It's unclear. Why does not LA simply say, "Translate from the Neo-Vulgate, with reference, as appropriate, to the best Greek and Hebrew texts?" The reason must be some academic fetish about not translating from a translation. It may be ecumenical fear of ridicule for putting Latin above Greek and Hebrew. But let us remember the Vulgate is not just another translation. It is a great monument of fidelity to and preservation of the Scriptures in the Roman Catholic Church. The 20th century saw an explosive flood of new English translations of the Scriptures, truly a "Bible Babel!" C.S. Lewis once shrewdly observed, "The less the Bible is read, the more it is translated." Clearly, we Catholics should stand by the Vulgate...

LA says we must have translations that conform to traditional Catholic understanding and worship and the teaching of the early Fathers (§41). The Greek Old Testament–called the Septuagint–should be consulted. The Old Testament holy name of God is not to be rendered Yahweh but by the equivalent of Dominus, that is, the Lord, Kyrios, etc. from Adonai, the Hebrew customary substitute name. Translators should pay close attention to patristic writings and to classical Christian art and hymnody when these illuminate the scripture (§41).

In Paragraph 42, we are reminded that Scripture is not just history, but mystery. It is a saving event today and still speaks to us. The translation should not conceal this but make it recognizable. LA teaches us to retain anthropomorphisms in God-language, such as God's "right hand," "face," "finger," and words such as "flesh," "horn," "seed," and "visit." Do not replace these by some well-intended abstraction or a so-called dynamic equivalent. Retain the words "soul" and "spirit," and avoid expressions of confusing or ambiguous sound (§§43-44)...

Part II, Section Three: Norms for Other Liturgical Texts

Let me summarize some of the paragraphs in this section briefly.

(§48): Let the wording of liturgy be memorable, so that it may enrich one's private prayer.

(§49): Allow biblical allusions in prayers to shine forth, manifesting correspondence, but we must avoid heavy over-elaboration of delicate biblical allusions.

(§51): Keep a rich lexicon of words, as in Latin, and not overuse terms such as "nourish" or "love."

(§52): Express the denotation, or primary sense, of words, so as to maintain their connotation, or finer shades of meaning. Translators must avoid "psychologizing," that is, for example, to water down a theological virtue to an expression of mere human emotion.

(§54): The key prayer words for God's causality, e.g., "grant," "give," "make," (in Latin, praesta, concede, fac) are not to be weakened into a "merely extrinsic or profane sort of assistance." We are to restore "And with your spirit" and the threefold mea culpa. The expression "thy spirit," I observe, occurs four times in the Pauline letters.

(§57): Respect the coherence or interconnectedness of the Latin Roman Collect prayer by maintaining the subordinate and relative clauses, the ordering of words, and the parallelisms. (This is good to hear. A major fault of ICEL translators around 1970 was to chop the Collects into two or three short sentences, destroying the coherence.)

(§59): Praise of Latin prayers for their "patterns of syntax, solemn or exalted tone, alliteration and assonance, concrete and vivid images, repetition, parallelism and contrast, a certain rhythm, and sometimes lyric quality." These should be noted and respected in the translation according to "the full possibilities of the vernacular language" in question.

(§60): Many liturgical texts are to be sung, therefore, the translation must then be suitable for singing likewise, but not through the use of mere paraphrases, nor of some hymn that is "considered generically equivalent."

(§61): The Latin chant hymns (such as Veni Creator, Adoro te, Ave Marts Stella, Dies Irae) are only a fraction "of the historic treasury of the Latin Church, and it is especially advantageous that they be preserved in the published vernacular editions, even if placed there in addition to hymns composed originally in the vernacular." (Is this preservation to be in Latin or English or both? LA does not say.)

This gentle exhortation to maintain some Latin chant hymnody is a plaintive reminder, I think, that much contemporary Catholic hymnody is profoundly inferior sacro-pop by contrast with the beautiful and prayerful ancient hymnody of Mother Church. These remarks remind us of the present ICEL Breviary, which has a mixed assemblage of good and bad, old and new hymns side by side with some Latin hymns.

(§65): The Creed must be rendered precisely according to the traditional Latin, including "I believe," and not "We believe." I hope this means a return to that exact Latin word "consubstantial" (with the Father). Curiously, I note a call for a literal version of "carnis resurrectionem" when the Apostles' Creed is used. That means to say "resurrection of the flesh" not of the body. I wonder why....

(§66): The support documents of the various books and rites, that is, the general introduction, preface or praenotanda, and rubrics must be published "in the same order in which they are set forth in the Latin text."

(§69): All the documents mentioned in §66, even their numbering system, must correspond. Any additions must have Vatican clearance, and so must their place of insertion. (The Vatican knows it is very annoying to go to a foreign church to say Mass and be unable to locate the Order of Mass because it is in a different part of the missal. As for our Canadian liturgical books, the current editions are horrendously overgrown, having three to five times more pages than the Latin books, and contain certain editorial difficulties.)

Part III: Preparation Of Translations And Commissions

This third and last part of LA begins (§70) by observing that Vatican II in Sacrosanctum Concilium (§36) entrusted to the bishops the task of translating the liturgical texts. In fact, however, the Vatican employs a permanent staff of professional translators who translate papal and Vatican documents of all kinds, including the encyclicals, into the six principal Catholic languages of English, French, German, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese. I do not know how many more languages they serve.

I am convinced that if these Vatican experts had done at least the English version of the new liturgy, I am sure we would have had a first-class job done in a fraction of the time and cost taken by ICEL, and far less damaging to the Faith. The liturgy is much more vital to the Faith than papal speeches. Paragraph 76 tells us that in future the Vatican will involve itself more in liturgy translation into the major languages. There is some provision for printing the Latin and English side by side in our official liturgical books (§116). One would think this desirable so as to maintain some use of Latin which was clearly called for in Sacrosanctum Concilium and other documents. It would also encourage singing the Kyriale parts in Gregorian Chant for greater prayerfulness.

Paragraph 80 of LA is very grave. It reminds bishops that the recognitio (or approval) of a liturgical text is an act of governance, is no mere formality, and is strictly required. The prior approval by the bishops has no legal force until Rome gives recognitio. I observe that LA does not translate this juridical term. Since the death of Pope Pius XII, it is clear that Vatican authority has been waning. One hopes that the LA insistence on the recognitio and its many other disciplinary exhortations about liturgy will help to purify the Church in her present crisis.

Even more significant are this paragraph's (§80) remarks on Lex orandi, lex credendi. This fundamental theological axiom about liturgy and faith finally appears only now after 80 paragraphs and 23 pages have gone by! Its treatment lasts only six lines, or 14 lines viewed more broadly. Pope Pius XII treated of this maxim or principle–"The law of prayer is the law of belief "–in five full paragraphs (§§44-48) of Mediator Dei (Nov. 1947). He shows that this principle is a "theological source"–a fons theologicus–and that Pope Pius IX used it to support and confirm the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. So also did previous popes and Councils when seeking to define a truth divinely revealed. So also did the Fathers of the Church when doubt or controversy arose over some truth. In other words, we must ask, "What has the Church always said when she prays?" The answer to this question, then, is what she believes. Her rule of prayer establishes or sets her rule of faith. In order to know the belief of the Church, learn what she says in her prayer. In Mediator Dei (§48), Pope Pius XII gives the traditional wording of the maxim used "Legem credendi lex statuat supplicandi" literally, "Let the law of praying establish the law of believing." We may ask, "Do new prayers recently inserted in the liturgy establish the Faith as much as ancient prayers in long and wide use by large numbers?" Obviously not. We remember the maxim of St. Vincent of Lerins: "Quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est," that is, "What was believed everywhere always and by all." But Pius XII also teaches the reverse sense of the lex orandi maxim: "The Liturgy must be conformed to the precepts of Catholic Faith as proclaimed by the supreme teaching power." In other words, the solemn public rules for believing must shape or establish the rules for praying. The early popes did this when they composed collect prayers for the Mass. Nevertheless, such a pope-author must be humbly certain of his personal faith before he writes, and he will surely be well aware of the existing Church's prayers before he adds his new one. He, too, is being established by lex orandi.

I have needed to clarify the lex orandi maxim in order to comment on what else appears in §80 of LA. There we see that the second or reverse sense of the maxim is emphasized, and the primary sense neglected. We are told, "Lex orandi must always be in harmony with [that is, be determined by] the lex credendi." Further, the prayers "must manifest and support the faith of the Christian people." These two verbs, "manifest" and "support," uncomfortably suggest that the faith of the people is a pre-existing thing that must be demonstrated and confirmed. This is partly true, of course. But it is worrisome to see this faith called "the faith of the Christian people." This could include protestants and whoever else–and probably does in the author's mind, given the strong ecumenical stance of today's minds within the Roman Catholic Church.

LA goes on to say that the liturgy is unworthy of God "without faithfully transmitting the wealth of Catholic doctrine from the original text into the vernacular version," so that the English prayer "is adapted to the dogmatic reality that the Latin contains." Unfortunately, this so-called "wealth of Catholic doctrine" or "dogmatic reality" of the new liturgy is not entirely found in Catholic tradition. What it is is the Novus Ordo: it is the new liturgy drafted by the Consilium under Archbishop Bugnini especially in the years 1964-69. It contains a large component of new prayers and countless changes in many if not most of the old surviving prayers. It shows doctrinal bias contrary to liturgical tradition. It could be called the abolition of the old Catholic lex orandi. Yes, it was badly translated by ICEL, of which I was a part. Yes, a new and better translation is... coming. But let us not lose sight of genuine Catholic liturgical tradition in our preoccupation with the new Roman, Vatican II liturgy.

The remainder of the third section of LA is concerned largely with procedures of interest to bishops, liturgical commissions, and publishers. Paragraph 108 calls for a common Catholic hymnal in the vernacular. Paragraph 124 reminds us that no text is to be added to a vernacular edition without prior approbation by the Congregation for Divine Worship.

I have described Liturgiam Authenticam as a detailed and demanding document. We have gone over a good many of its details and demands. The bishops and their advisors will have a lot of homework. The Congregation of Divine Worship says that from the day of LA's publication "a new period begins" for the vernacular liturgy (§131). In its final paragraph (§133), it hopes "this new effort will provide stability in the Church," give firm support to liturgy, and lead to a solid renewal of catechesis. Well, we'll see. May God's will be done.

Fr. Stephen Somerville was born in England (1931) and soon after moved with his family to Toronto, Canada. He was ordained in 1956. He has earned several music degrees and various appointments to liturgy and music commissions along with seven parish appointments in his career. He currently is chaplain for the Regina Mundi Retreat Center, where he has celebrated the Latin Mass. He has recently made the acquaintance of Fr. Jean Violette, Canada's District Superior for the Society of Saint Pius X. This article was transcribed from his talk to the Confraternity of Catholic Clergy (July 8-11, 2002). He asks for our prayers.