The Second St. Francis

T. Francis Ryan M. Gerhold

|

In 1181, Almighty God, seeing that the hearts of men were turning cold and away from His Church, raised up St. Francis of Assisi. St. Francis's mission was to remind the world of the sufferings of Our Lord Jesus Christ Crucified by founding a religious order called the Friars Minor (Franciscans). The Franciscans would help revive the Church by the heroic practice of the evangelical councils: voluntary poverty, firm obedience, and perfect chastity.

Our Lord rewarded St. Francis for the completion of his heroic mission by impressing on his body the wounds of His crucifixion, known as the stigmata. It would bring much glory to both St. Francis and the Franciscans, and thus help to re-kindle true charity in the hearts of men. But, human nature being corrupted with original sin, men forgot the holy example of St. Francis and the sufferings of Our Crucified Savior.

In 1887, Almighty God, again seeing that the hearts of men were not only turning cold but completely apathetic, raised up a second St. Francis. This "son of St. Francis" would be known as Padre Pio. Padre Pio would bear the stigmata, the first known priest in the history of the Catholic Church to receive this mystical gift, for St. Francis himself was only a deacon. Padre Pio lived a life of constant prayer, suffering, and wonderworking, immersed in an intense love of the Crucified Savior, and by these means he purchased souls for God.

Padre Pio, known as Francesco Forgione before he became a Capuchin (a reformed order of the Franciscans), was born on May 25, 1887, the third of eight children. He was reared in the small town of Pietrelcina, Italy. His parents were simple, God-fearing shepherds who instilled a great love of God in their children. At five years of age Francesco decided to consecrate himself to God forever. Later that same year he had his first mystical experience.

One day when I was kneeling in front of the Blessed Sacrament by myself, I heard a voice come from out of the Tabernacle, it said, "You will be scourged and crucified for love of me, but you will bring many souls back into my flock."1

Despite the beginning of the devil's violent attacks and apparitions, Francesco's desire to consecrate himself to God grew even stronger. At age 11 he received his first Holy Communion. He was an exemplary student, not for his knowledge, but for his conduct and perfect attendance. He would leave for school an hour early so that he could serve daily Mass at the parish church of Pietrelcina. This annoyed his teacher, Don Domenico Tizzani, an apostate priest living in sin. He would cause him much suffering and humiliation, but many years later when Francesco would return to Pietrelcina, he brought his teacher back to the Faith. At 15, Francesco would consecrate his life to God. This aroused Satan. Padre Pio spoke about the ensuing internal struggle some 22 years later:

Dear God! Who can describe the martyrdom I went through in my inmost being? Even the memory of that internal combat makes my blood freeze in my veins, although almost twenty-two years have passed since then. I heard the voice of duty telling me to obey you, O true and good God! But your enemies and mine are tyrannized over me, they dislocated my bones, they mocked me and caused me to writhe in agony.2

Francesco took the Capuchin habit on January 22, 1903, in the novitiate of Morcone, and changed his name to Fra Pio (or, Brother Pius, after Pope St. Pius V). His novitiate lasted four grueling years during which the devil attacked him and even one time appeared in his cell in the form of a monstrous black dog with red eyes. Three years later, Fra Pio made his final vows. Under obedience to his superiors, he began studying for the priesthood.

His seminary days were marred by ill health due to the winter cold, his many fasts, penances, and tuberculosis. He was frequently sent home for rest and fresh air to recover his strength. One time he was sent home with a very high fever. The family doctor tried to take his temperature, but almost as soon as he had placed the thermometer (which read 144°F) into his mouth, it burst. The doctor yelled, "How is this possible?" Fra Pio said, "I don't know, you're the doctor."3

|

Archbishop Lefebvre meeting Padre Pio at the monastery of San Giovanni Rotondo in 1967. |

Fra Pio was ordained to the priesthood on August 10, 1910. In a letter to his spiritual director, he wrote: "My heart is brimming over with happiness and I feel more and more prepared to meet any suffering which may come, as long as it is a matter of pleasing Jesus." Within weeks after his ordination he was once again sent home with what appeared to be a very mysterious illness. This illness would baffle even the best of surgeons and would cause Padre Pio inexpressible sufferings. Padre Pio remained at home until February 1916. His spiritual director, realizing that Padre Pio's sickness was not natural and part of God's design to purify him, sent Padre Pio to Our Lady of Grace Capuchin Monastery in San Giovanni Rotondo, where he would spend the rest of his life. In December of 1916, Padre Pio was drafted into the Italian army and assigned to the 10th Medical Corps. His military service would last 182 days, although he would spend a good number of them on leave for illness. Apart from his military service Padre Pio left San Giovanni only two or three times throughout his lifetime. In May of 1917, he traveled to Rome with his sister Graziella who was to become a Bridgettine nun.

Padre Pio's priestly duties at this time consisted in helping the parish priest to administer the sacraments, but he was refused permission to hear confession due to his lack of knowledge in moral theology and his ill health. This did not diminish his priestly zeal for souls. He began to correspond with a few pious souls, offering up his sufferings as a victim for them and for the souls in Purgatory. He learned that the love of God was inseparable from suffering, and was the path by which the soul must make its spiritual ascent towards God. Prayer became for him more passive and his knowledge of the greatness of God and man's poverty grew. His soul began experiencing mystical phenomena, which would continue to a greater or lesser degree for the rest of his life.

Padre Pio's soul began to be purified by the "night of the senses," that is, by great spiritual suffering. He felt his soul lost in a chaotic maze, plunged into total desolation, as if he were in the deepest pit of hell. During this "dark night," Padre Pio's battles with Satan were relentless, and he experienced both spiritual and bodily torments. The devil also used diabolical tricks in order to increase Padre Pio's torments. These included apparitions as an "angel of light" and the alteration or destruction of letters to and from his spiritual directors. In the end, the devil was not able to hold Padre Pio back from his advance to God, and with the help of Our Lord, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and his Guardian Angel, he would conquer the dark night.

|

On August 5, 1918, Padre Pio received the transverberation, which, according to St. John of the Cross, is "the soul being inflamed with the love of God which is interiorly attacked by a Seraph, who pierces it through with a fiery dart. This leaves the soul wounded, which causes it to suffer from the overflowing of divine love." This transverberation left Padre Pio in what appeared to be another dark night of the soul which lasted seven weeks. "During this time his entire appearance looked altered as if he had died," said one of his fellow Capuchin brothers. "He was constantly weeping and sighing, saying that God had forsaken him." On September 20, 1918, there was a drastic change: all the pains of the transverberation calmed, leaving Padre Pio in a profound peace. He suddenly found himself kneeling before a heavenly creature who would inflict the wounds of Our Lord upon Padre Pio. Here is how he described it to his spiritual director:

On the morning of the 20th of last month, in the choir, after I had celebrated Mass, I yielded to drowsiness similar to a sweet sleep. All of my internal and external senses and even the very faculties of my soul were immersed in an indescribable stillness. Absolute silence surrounded and invaded me. I was suddenly filled with great peace and abandonment that effaced everything else and caused a lull in the turmoil. All this happened in a flash.

While this was taking place I saw before me a mysterious person similar to the person I had seen on August the 5th. The only difference was that his hands, feet, and sides were dripping with blood. This sight terrified me and what I felt at that moment is indescribable. I thought I should die and really should have died if the Lord had not intervened and strengthened my heart that was about to burst out of my chest. The vision then disappeared and I became aware that my hands, feet and side were dripping with blood.4

|

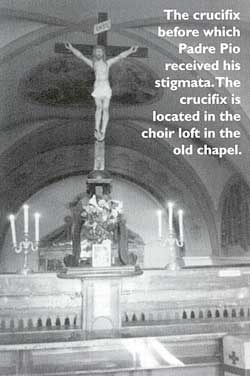

The crucifix before which Padre Pio recieved his stigmata. The crucifix is located in the choir loft in the old chapel. |

Padre Pio attempted to hide his stigmata out of humility and embarrassment, but with the amount of blood that he was losing it was not long before the community noticed. One of his Capuchin brothers noticed his sheets heavily stained with blood and told his superior, who at once questioned Padre Pio as to its source. At first Padre Pio was reluctant to answer, but forced under obedience he revealed his stigmata. Almost overnight all of San Giovanni seemed to know, and soon faithful from all over the countryside of Italy began to converge on the monastery see this stigmatized priest. This caused Padre Pio even greater embarrassment, not because of the stigmata, but because he was now the center of attention.

Padre Pio's stigmatization stirred up devotion among the faithful and aroused the curiosity of scientists and physicians. Padre Pio's stigmata were examined over 30 different times by doctors Catholic and atheist. All came to the same conclusion, that on Padre Pio's hands and feet there were anatomical lacerations, round in shape, about ¾-inch in diameter, with clearly defined outer edges. There was also a very deep laceration in the left side of his chest, which was three inches long. All the lacerations were covered with the reddish-brown scabs which appear normally for any wound, however, one doctor reported:

On contact with the air, blood usually begins to coagulate and healing process starts, but in Padre Pio's case, the edges of scab begin to flake towards the center of the wound and eventually the whole scab falls off. His wounds appear to be continually bloody while scabs keep forming and flaking off. The depth of the wounds on his hands and feet can not be measured, for they appear to go completely through. There is no natural way to explain this phenomenon.5

The Holy Office in Rome became aware of Padre Pio's stigmata and by Christmas of 1920 had its reasons to forbid him to hear confessions, baptize, or to celebrate Mass in public. He was not allowed outside of his monastery to visit the sick, to administer Extreme Unction to the dying, or to perform any pastoral duty. These restrictions remained in force for two years.

On January 22, 1922, Pope Benedict XV, who had been sympathetic to Padre Pio, died. The new Pope, Pius XI, influenced by the opposition that had grown around this extraordinary monk, mainly from jealous clerics, further restricted Padre Pio. He was not to leave his cell except to celebrate Mass, and was to speak with no one, including his own spiritual director. Faced with the impossibility of living constantly in his cell, Padre Pio moved his bed to the library of the monastery.

Five years after Padre Pio received the stigmata, he found himself utterly isolated within his own monastery. His hands were kept bandaged and covered with half gloves. The wound of his side bled profusely. He walked in the shadows of the hallways even on his way to the chapel and was allowed to celebrate Holy Mass only by himself. In the early morning hours he would go silently to the chapel on the second floor, celebrate Mass–his only consolation–and return without being permitted to address anyone.

Despite the protests of the faithful of San Giovanni Rotondo against these restrictions placed on him by Rome, Padre Pio persevered in solitude, prayer, and suffering, submitting at all times with great confidence to the will of his superiors. In early July of 1933, Pope Pius XI retracted the mandate against Padre Pio, apologizing for having had received false information about his stigmata and begging for his forgiveness. On July 16 of that year, Padre Pio was permitted to again celebrate Mass in public and eight months later he was re-permitted to hear confessions.

Padre Pio celebrated Mass at 5 a.m. every morning. It lasted from two to four hours and he would often go into ecstasy, shedding so many tears that he would almost have to leave the altar. During the Consecration, which lasted anywhere from five to ten minutes, Padre Pio's complexion changed from one of peacefulness to one of a man crucified. His eyes appeared as though he was actually witnessing the death of Christ on the cross. Sometimes his facial features shone with light, enough to convict and convert the most hardened of sinners.

At the Memento of the Mass, where the priest remembers for whom or what the Mass is being offered, Padre Pio entered into an ecstasy. It seemed as if he might be remembering the entire world. His superior, Fr. Agostino, reported that Padre Pio's Memento lasted no less than 15 minutes. Often Fr. Agostino had to give him a mental command to continue the Mass, to which Padre Pio promptly responded. One day someone asked Padre Pio why he took so long during the Memento. He replied, "I see all the people who ask for my intercession during the day, but I also see many souls from Purgatory, so many that you would need a mountain to hold them all."6

|

Padre Pio's confessional |

|

Outside of Holy Mass, Padre Pio's greatest love was for the confessional. Here he could spend up to 18 hours a day, hearing up to 200 confessions or more. Besides the gift of the stigmata, Padre Pio also had the gift of discernment of soul, which allowed him to know the state of soul of his penitents, including its sins in detail.

He was also endowed with the gift of prophecy, so he knew the best advice to give to the penitent. But by 1940, a penitent wishing to go to confession to Padre Pio would have to wait up to two days.

In one case a woman who had had an abortion earlier in her life, but had since gone to confession and been forgiven, came to confess to Padre Pio. She began describing a recent dream to him in which a man approached her dressed as a bishop or cardinal, shaking his finger at her. She was very frightened at this and wondered what it meant. Padre Pio told her, "That was the cardinal you aborted who would have saved the Church." The woman fainted and had to be carried out of the confessional.

Padre Pio was also blessed with the gift of miracles. One doctor who visited San Giovanni Rotondo called him a "Walking Miracle." For many years Padre Pio only received one hour of sleep at night (from 12 a.m.–l a.m.) and consumed less than 500 calories daily while actually gaining weight. He also had the gifts of bilocation, that is, to appear to be bodily in two places at the same time, and levitation. During World War II the Allies sent a message to the civilian residents of San Giovanni Rotondo to evacuate because the town would be destroyed within 48 hours by air raids. This caused a great panic. The mayor ran to Padre Pio screaming, "We have to leave; they are going to bomb the town!" Padre Pio said to him: "Tell all the people to go back to their homes and pray. There will be no bombing." Two days later, 28 American B-29s were sent in to bomb San Giovanni. As they flew towards the town at 15,000 feet altitude, the bombing pilots saw a monk in the sky pointing at them. Overcome by amazement and fear, they turned back and dropped their bombs in an empty field 25 miles south of San Giovanni Rotondo! Some years later one of the pilots came across a picture of Padre Pio, and came to San Giovanni to see this extraordinary monk. He attended Padre Pio's Mass and was about to leave, when Padre Pio came out of the sacristy and turned to the pilot to say: "We were high flying that day, weren't we?!"

Once a woman came to see Padre Pio, depressed because her son was fighting in the war. She begged the monk to protect him. Padre Pio promised that her son would be fine and that he would protect him. Months later her son was in a foxhole under fire by mortar shells. The frightened boy was reciting his Rosary begging God to spare him. Suddenly a monk appeared before him giving him an order: "Boy, get out of the foxhole!" Too scared to move, the boy didn't respond. Again, the monk ordered, "Get out of the foxhole!" Once again, the boy failed to respond. Finally, the monk grabbed the boy and tossed him out of the foxhole just at the moment a mortar hit. The boy looked around for the monk who had saved his life and found nobody. When the boy returned home he noticed a picture of Padre Pio in his mother's room and realized that this was the monk who had saved him. He went to San Giovanni, attended Mass, and tried to talk with Padre Pio, but before he could utter a word Padre Pio turned to him and said, "We nearly got blown away that day."

Padre Pio used his gift of bilocation to work miracles, and to gain extra time for prayer. He was said to have bilocated to the Holy House of Loreto, Italy, to make holy hours. He stressed the need for prayers to hold back the wrath of God. He especially insisted on the daily Rosary. He called it "The Weapon." About prayer, he said:

A person who does not pray and meditate is like someone who never looks in the mirror before going out, to see if he's tidy or not. While on the other hand, a person who meditates and turns his mind to God, who is the Mirror of the soul, seeks to know his faults, tries to correct them, moderates his impulses and puts his conscience in order.7

|

The older chapel in the monastery. |

|

Padre Pio also did exorcisms when asked under obedience to do so. In 1964, a possessed woman was brought to San Giovanni to be exorcised. She was foaming at the mouth and shrieking, "No, No, not Pio." As soon as the woman saw Padre Pio, she turned pale, and her body became stiff. Then the devils inside of her began to speak: "Pio, we know you and you will see us tonight!" The devils kept their promise and around l a.m. there was an earthquake in San Giovanni, with enough force to damage the foundation of the monastery. While the earthquake was taking place loud screams were heard coming from Padre Pio's cell. His superior ran to the cell and found Padre Pio lying on the ground. He had suffered two black eyes and facial wounds. The superior noticed a blue pillow under his head. He asked Padre Pio what had happened. He said "Sorry to wake you, Father. They came again, but Our Lady saved me." Some days later a woman asked Padre Pio if the "little devils" beat him up. He turned to her and said, "Little devils?! They were big, and they beat me with the hoofs of Lucifer."8

On February 17, 1965, Padre Pio wrote to Pope Paul VI asking permission to continue celebrating the traditional Mass in Latin. He was granted this request and celebrated this Mass exclusively until his death.

In November of 1966, Padre Pio's health began to deteriorate. Despite the assistance of the best physicians, nearly 50 years of constant austerities had worn out his body. But Padre Pio continued his extraordinary apostolate for two more years. For most of this time he was confined to a wheelchair in which he constantly prayed the Rosary. He was still able to celebrate daily Mass but only heard a limited number of confessions. Even still, pilgrims continued to visit the monastery to receive his blessing.

September 20, 1968, was the 50th anniversary of his reception of the stigmata. On that date, the stigmata of Padre Pio miraculously vanished. For the next two days, Padre Pio was too weak to celebrate Mass but still prayed his Rosaries. On September 22nd, he celebrated his last Mass with great difficulty and collapsed at its finish. At 2 a.m. the next day he received Extreme Unction and at 2:30 a.m. passed away peacefully as he had predicted he would.

On September 26, 1968, about 100,000 people were present for Padre Pio's Requiem Mass and burial. It was said that a strong scent of roses emanated from his body. His holy death made world headlines in the news media. As in 1226 when the faithful of Assisi carried the body of St. Francis in procession, so did the did the faithful of San Giovanni carry the body of Padre Pio. Ever since then lines of pilgrims have come to pray at his tomb.

On November 23, 1968, Msgr. Antonio Cunial, Apostolic Administrator of Manfredonia, took appropriate steps to arrange for the case of his beatification and canonization. On March 20, 1983, Padre Pio was declared Venerable and on May 2, 1999, Blessed. On June 16, 2002, 33 years after his holy death, Pope John Paul II canonized Padre Pio a Saint.

St. Padre Pio, pray for us.

Ryan Gerhold is from the Philadelphia, PA area, the third eldest of eight children. He assists at the Latin Mass at St. Jude's (Eddystone, PA). After being a lay volunteer at St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary for a year (1999-2000), he entered there and has just completed his second year of seminary studies. His appreciation for St. Padre Pio is because he never celebrated the Novus Ordo Mass. The Gerhold Family lives three miles from the Padre Pio Center in Barto, PA, which he prays will become traditional Catholic someday.

Photos on p. 15 by Miss Heather Nicole Hamtil.

1. Bernard C. Ruffin, Padre Pio: The True Story (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 1982), p. 15.

2. Padre Pio of Pietreclina, Letters, 3 Vols. (San Giovanni Rotondo, 1984), 3:73.

3. John A. Schug, Padre Pio: He Bore the Stigmata (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 1976), p. 64.

4. Padre Pio, Letters, 1:1217.

5. Schug, Padre Pio, p. 79.

6. Fr. Alessio Parente, O.F.M., Cap., Padre Pio (Pietrelcina, 1988), p. 25.

7. Charles Mortimer Carty, Padre Pio the Stigmatist (Rockford, IL: TAN Books and Publishers, 1973), p. 235.

8. Ibid., p. 110.