Moissac: The Abbey of Saint Peter

Dr. Marie-France Hilgar

|

The interior of the church today with the relocated Novus Ordo Altar |

The monks of St. Peter of Moissac attribute the foundation of their abbey to Clovis, the first king of France (481-511), but this honor more likely belongs to a descendant of his, Clovis II (639-657). Many monasteries were established a little later in southwestern France by King Dagobert and his sons, for economical, administrative, and political reasons as well as for religious purposes, and the abbey of St. Peter was no exception.

The Moslems pillaged the abbey when they laid siege to Toulouse, France, in 721, and a second time, after their defeat at Poitiers, on their way back to Spain in 732. The abbey was invaded a century later, first by Normans, then by Hungarians. But dangers were domestic as well as foreign, for in the second half of the ninth century, the count of Toulouse used the abbey as a source of revenues. In 1031, the roof collapsed, and 12 years later, a fire caused severe damage and the monks were without the means to rebuild.

The abbey was later saved and preserved through an affiliation with Cluny. By its geographical location on the Tarn River, not far from where it joins with the Garonne, Moissac gained significance when Cluny, the sizeable Burgundian abbey, prepared to take an active part in the affairs of Spain. Moissac was a major stopover to the Iberian peninsula. In 1048, Moissac became a conventual priory of Cluny, and was therefore under its authority. But Moissac retained its own abbot, to which post Father Durand was nominated, who had done his novitiate in Cluny.

Father Durand devoted his life to the material and spiritual renovation of the monastery. Cluny endowed Moissac with numerous monks who gave the community added strength, and with several manuscripts, which not only enriched the library but also provided valuable experience for the copyists. Father Durand became so renowned that he was chosen as the bishop of Toulouse in 1059, but he retained the direction of Moissac. On November 6, 1063, he consecrated the new church which was built under his command. The artistic activity that he had set in motion was continued by his successors. Father Anquetil (1085-1115) erected new monastic buildings around a large cloister, sumptuously decorated with sculptures. The cloister was finished in 1110, just four years after Pope Urban II had blessed the abbey and consecrated the altar, which was done on May 13, 1096.

|

This is the crucified Christ installed near the organ on a cross entwined with vines symbolizing the Tree of Life. |

Belltower and entry door |

Shortly afterwards, the great period of spiritual and artistic dissemination came to an end. The faithful promoted other religious establishments, especially Cistercian monasteries. The long period of stagnation was followed by a privileged time which brought a temporary general renewal in southern lands under the government of Bertrand de Montagut (1260-95). This abbot restored practically all of the buildings of Moissac to an extent which would be nearly impossible for his followers to maintain. He assured the protection of the monastery by surrounding it with ramparts.

Then came the tribulations of the Hundred Years' War and the black plague, which decimated the community in 1348. Renovations for the abbey could be undertaken only after the defeat of the English. Fr. Aymeric de Roquemaurel (1431-49) repaired the portion of the cloister where the fountain was located, and began special efforts to renovate the church. His work was continued by Pierre de Carmaing (1449-84), who obtained official documents from the Pope (in 1461 and 1466) releasing Moissac from its affiliation with Cluny. This newfound freedom, however, did not help, but rather accelerated decline. Maintaining the walls became impossible. The Wars of Religion forced the priests to house soldiers and the proximity of the market encouraged merchants to conduct their dealings even inside the church.

|

The carved-stone Pieta (1476) includes the small images of its famous benefactors which kneel in veneration in the foreground. |

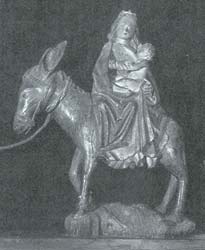

The Flight into Egypt graces |

The community underwent further neglect. The library was the first to suffer. It was bought by Prime Minister Colbert who had the books shipped to Paris in 1678, which later became part of the then royal library in 1732. In 1767 Louis XV authorized the demolition of part of the monastery and its adjacent structures. The Revolution did little harm to the buildings themselves, but vandalized the furniture and decorations. Soldiers hammered off the heads of the saints on the capitals of the cloister. The church and cloister were placed on sale, and the latter, purchased by a patriotic citizen, was offered to the town, thereby exposing the building to the most unworthy causes. The garrison stationed there during the First Empire ruined the ancient enameled-tile pavement. In the mid-19th century a plan was begun to run railroad tracks through the cloister. This plan created such a scandal that it drew the attention of the Administration of Historical Monuments, which asked Viollet-le-Duc to start the restoration.

|

This Blessed Virgin Mary is part of the Entombment scene in another side chapel of Moissac which includes Joseph of Armimathea and Nicodemus. |

This stone image of St. Mary Magdalen |

Of the medieval abbey of Moissac there survive today the Romanesque cloister built in 1110, the church on its south side constructed in the 15th century, incorporating the walls of the Romanesque church, the tower and porch which preceded the latter on the west, and several conventual buildings to the north and east of the cloister. Upon entering the church one is struck by the luminosity accentuated by the yellow painting on the walls, the pattern of which was found in the older part of the church. The gorgeous old main altar and the Renaissance closure of the sanctuary have survived Vatican II. The old altar is no longer in use and a table has been set up in a sideways arrangement on the north wall of the nave underneath the 17th-century organ. Around the apse, the second chapel on the right exhibits a beautiful stone Pieta. In the central group, the Virgin of Pity holds on her lap her Son who has been taken down from the cross. At their feet are two small figures representing the donors John and Gaussin de la Garrigue, consuls of Moissac. To the left is St. John the Baptist and to the right, St. Mary Magdalen with her long tresses. The scene is dated 1476. In the following chapel is a charming Flight into Egypt also dating from the end of the 15th century. Seated on the donkey, Mary holds the child Jesus in her arms. In the last chapel on the right is found the famous Entombment and eight persons figured. This also dates from the 15th century. It is made of painted wood. On the right side of the organ is the admirable Romanesque crucifix done in the 12th century. Our Lord is wearing a flowing perizjonium, or long garment, which reaches to His knees. He is attached to a cross symbolizing the Tree of Life. Under the organ is a white marble sarcophagus of the seventh century, probably the tomb of one of the first abbots of Moissac. The 18th-century pulpit still hangs from a pillar on the right side of the church.

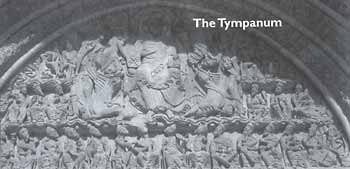

If Moissac draws so many visitors these days, it is because of its tympanum and its cloister. The latter with its many famous capitals is rightly considered the most beautiful one left in the world. In the tympanum of the south portal, the sculpture of Moissac is truly monumental. It is placed above the level of the eye and is so large as to dominate the entire entrance. It is a gigantic semicircular relief, over 15 feet in diameter, framed by a slightly pointed archivolt in three orders. Its great mass is supported by a magnificently ornate lintel, a sculptured trumeau, or pillar, representing Paul and a bearded prophet, and two doorposts on which are carved the figures of Peter and the prophet Isaias. The portal is sheltered by a salient barrel-vaulted porch, decorated on its lower walls with reliefs representing incidents of the Infancy of Christ, the story of Lazarus and the Rich Man, the Punishment of Avarice and Unchastity. In its grouping and concentration of sculptures, the porch is comparable in enterprise to an arch of triumph. The tympanum itself is a remarkable work of engineering and architecture, for 28 blocks of stone were brought together to form its surface.

|

|

|

|

The meal of the rich man, Dives (at right), as dying Lazarus is cared for by the dogs (left). |

||

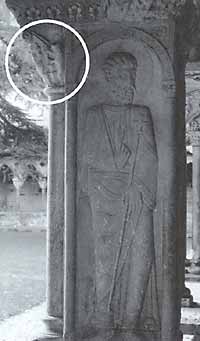

| St. Peter on the left side of the entry door under the Tympanum. |

|

St. Andrew is carved on the northwest pier of the cloister. |

On the tympanum, around a central group of a gigantic crowned Christ enthroned in majesty with the four symbols of the evangelists and two seraphim, are placed the 24 elders bearing chalices and various stringed instruments, all with heads turned up toward Our Lord. Despite the symmetry, there is a great variety in their attitudes, the positions of their hands, their feet, and their clothes.

When the visitor enters the cloister, he will immediately admire its rectangular plan, the disposition of its arcades and alternately single and twin colonnettes and the brick piers with grayish marble facings at the ends and center of each side, except for the central pier of the south gallery, which is a monolith of reddish marble.

On the inner side of the four corner piers, facing the galleries, are coupled the almost lifesize figures of Peter and Paul (southeast), James and John (northeast), Philip and Andrew (northwest), Bartholomew and Matthew (southwest). Simon stands on the outer side of the central pier of the west gallery, facing the garden of the cloister. On the inner side of the same pier is the inscription that records the building of the cloister (1000). On the corresponding side of the central pier of the east gallery, in front of the old chapter house of the abbey, is represented the abbot Durand (1047-1072). All these figures are framed by columns and by arches inscribed with their names. The figures are so slight in relief that they appear to be drawings rather than sculptures. The body is seen in full view but the head is almost in profile, and the eye which should gaze to the side is carved as if beholding us. The feet are not firmly planted on the ground, but hang from the body at a marked angle from each other. The hands are relieved flat against the bodies, the bent leg is necessarily rendered in profile. The unmodeled bodies are lost beneath the garments.

|

A double capital found in the eastern gallery of the cloister first displaying the end of the alphabet, and then the final five letters which are: "D(eu)S IN N(omine) [tuo salvum me fac],..." that is, "Save me, O God, by thy name,..." which is the beginning of Psalm 53. |

|

The capitals are 76 in number, alternately single and twin like the colonnettes which support them. Forty-six of them are historically punctuated, giving us scenes of the Bible and the lives of saints. The scenes are spread out on all four faces of the capitals. Inscriptions often name the figures represented. On several capitals, not only the names of the characters, but their actual words, are reproduced. Occasionally, as on the capitals narrating the miracle of St. Martin and the fall of Nabuchodonosor, whole lines from the text illustrated are copied on the imposts above the figures. When the sculptor of Moissac wished to represent the story of Adam and Eve, he did not isolate a single incident from the biblical text but carved upon the same surface the Temptation, the Divine Reproach, the Expulsion, and the Earthly Labors of the fallen couple. Adam appears four times upon this one relief. We are asked to regard the figures in a sequence in time as well as space, and to read them as we read the text that they illustrate. The same primitive continuity of narrative occurs on most of the figured capitals of the cloister. The same figure rarely appears twice on a single side of a capital. An exception is the Virgin of the Annunciation and the Visitation. On the same capital the magi approach the Virgin from the right while the Massacre of the Innocents proceeds from Herod seated at the left. The historical order of the Adam and Eve capital is right to left, of the Annunciation and Visitation from left to right: there is not always a strict order or direction in scenes placed on the four sides of a pyramid.

When looking at the four sides of each capital, the visitor ends his viewing with the feeling of being on a pilgrimage, of being invited to meditate on the "living stones" of Moissac.

Dr. Marie-France Hilgar is a native of France, mother of four children, and assists at the Latin Mass at Our Lady of Victory Church, Las Vegas, NV. She is Distinguished Professor of French at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and International President of the Foreign Language Honor Society. She specializes in 17th-century history and has authored several books and more than 100 articles.