"Teach Me!" Part II

![]()

Fr. Hervé de La Tour

In a conference he gave 50 years ago, the renowned Dominican educator, Fr. Roger-Thomas Calmel said:

Simply to teach some elements of Thomistic philosophy to our seniors is not enough. We must put our whole education from kindergarten to 12th grade under the vital influence of Thomistic principles.1

St. Thomas is indeed the Common Doctor, the universal teacher who leads our minds to unchanging truth. In my previous article [see "Teach Me!" in The Angelus, June 2001, pp. 2-15], I explained that the problem of modern education was the false philosophy which had inspired it. We showed the main errors of René Descartes and contrasted them with the teachings of St. Thomas. We made some suggestions on how to counteract the Cartesian influence in our own schools.

Why did I focus on Descartes? Because he inaugurated a new orientation in philosophy. His system of thought was no longer imbued with Catholic principles, but with rationalism. Theology was eliminated from the curriculum. Mathematics took the place of metaphysics as the fundamental subject. Without the supernatural wisdom of theology and the natural wisdom of metaphysics, sciences were not coordinated into an harmonious whole. They no longer led men to appreciate God's order in creation, but became means to make man's life more comfortable on this earth.

Descartes lived in the 17th century. His rationalistic spirit led in the following century to the writing of the famous Encyclopedia edited by Diderot and D'Alembert with the support of men like Voltaire. This work provided the educated world of the Age of Enlightenment with a summa of the new learning in opposition to the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas. In it, technology was seen as the source of true progress. Man was born to enjoy this world through machines, but he was unable to do so as long as his intelligence was perverted by the system of education favored by the Catholic Church. Therefore the first step in the liberation of mankind was to free the immature mind from the tyranny of priests. This is why the Society of Jesus—the Jesuit Order—the greatest teaching order at the time and the chief organ of Catholic Counter-Reformation for two centuries, fell victim to the propaganda of the rationalist minority. While there were still many good minds within the Society of Jesus, many Jesuits had unfortunately become contaminated with the errors of Descartes.

For all that, the suppression of the Society was a great tragedy since it left no opponent to refute the enemies of the Church then preparing the French Revolution (1789). In his book The Crisis of Western Education, historian Christopher Dawson explains that it was in the 18th century that the destruction of the classic system of education was consummated. Under the influence of the new ideas, the old educational traditions of the monastic schools, the medieval universities, and the humanist colleges became discredited. The revolutionaries sponsored their own educational programs and all the schools were put under secular control. The radical opposition between Catholic education and modern education was nowhere more apparent than in France. The religious and secular worlds were completely divorced. The contrast between the educational ideals of St. John Baptist de la Salle and those of Jean-Jacques Rousseau was obvious.

This may not be as clear in countries other than France, but nevertheless we must know there is everywhere a Catholic ideal of education which is in opposition to modern perspectives on the same subject. This has been pointed out by Popes Pius XI and Pius XII in their encyclicals and allocutions. Archbishop Lefebvre often said that the Society of Saint Pius X had not been designed as a teaching order, but that it had been forced to take over boys' schools out of necessity because qualified people were unavailable. It is a fact that Divine Providence allowed several congregations of teaching sisters to remain traditional, whereas all the congregations of teaching brothers (Salesians, Marists, Christian Brothers, etc.) became infected by modernism. So the Society of Saint Pius X has had to "fill the gap" and open schools for the children of the families assisting at Mass in its priories and missions.

This enterprise has met with more or less success depending upon various factors, such as, the time the priest could dedicate to the running of the school, his competence and his interest in the field of education, the teachers he could find, the cooperation of the parents, etc. For the past 25 years the Society of Saint Pius X has been doing the best it could with the means at its disposal to provide children with a Catholic education.

Now that we have a little experience in this domain, it seems that the moment has come to look back on our achievements. We need to examine the fruits of our schools and see if we are satisfied with the type of graduates we are producing. And if we see that the goals of a true Catholic education have not been sufficiently attained, then we need to rectify the means so as to better attain these goals. The goal of Catholic education was declared by Pope Pius XI in Divini Illius Magistri (1929) [available from Angleus Press. Price: $4.25]. It is to "co-operate with divine grace in forming the true and perfect Christian."2 And what is this true Christian? The pope defined it very clearly: It is the supernatural man who thinks, judges, and acts constantly and consistently in accordance with right reason illumined by faith. In other words, the fruits of our schools should be men of character with profoundly Catholic minds, men truly living an interior life, men sincerely desiring to "restore all things in Christ."

The enterprise of opening schools without previous experience in education, without a tradition such as exists in a teaching order of religious, is daunting. But because it is clearly God's will, we can count on His grace to remedy our insufficiency. This does not dispense us from doing what is in our power to improve our schools; that is why I indicated in "Teach Me!" five practical suggestions to improve their status.

Generally, we should find our inspiration in the wisdom of our predecessors. Pope Pius XI speaks about "the array of priceless educational treasures which is so truly a property of the Church, this incomparable and perfect teacher."3 When we look at the history of the Church, we see how our most admirable Mother was able to adapt herself to all epochs of mankind in order to teach her children. This diversity is one of the marks of the true Church.

In one of his "historical sketches," Cardinal Newman summarized the spirituality of three great teachers: St. Benedict, St. Dominic, and St. Ignatius. Each corresponds to a period in the history of the Church, roughly, the primitive Catholic Church, the Middle Ages, and the period of the Counter-Reformation. The institutions they created—namely the Benedictine school, the Dominican university, and the Jesuit college—fulfilled a need, being most perfectly adapted to a particular historical situation. But as pointed out by Cardinal Newman, "The Church still has both Benedict and Dominic at home, though she has become the mother of Ignatius." It is interesting to note that the great 20th-century minds of the renewal in Catholic education synthesized all three traditions. Gregorian chant (Benedictine), Thomistic philosophy (Dominican), and the humanities (Jesuits) were all part of the educational ideals of men like Fr. Calmel and André Charlier.

The Benedictine, Dominican, and Jesuit institutions are only three of the most famous in the history of the Church. Other educational treasures are at our disposal. The figure of St. John Bosco and his Salesian order come to mind. This great educator took a fatherly interest in his boys. He fostered a "family spirit" through which the teachers and students were united in joy and peace. In this friendly atmosphere of mutual trust, the boys developed an interior desire to follow the rules in order to please God and their superiors. This result could be obtained because the pupils were almost at all times under the vigilant eye of the teachers who would talk, work, and play with them. This "preventive" system removed from the students the possibility of committing faults.

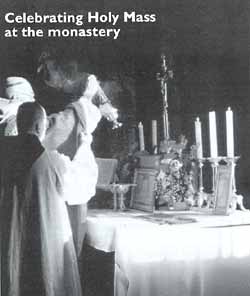

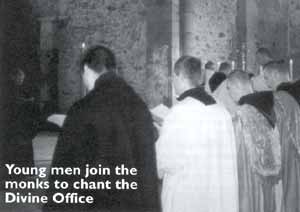

The Society of Saint Pius X, educating the boys of the 21st century, was able to profit from the wisdom of holy Mother Church, wisdom which shines forth in the life and writings of the numerous saints which she has produced in the past two thousand years. Thus recently, a group of 8th-grade boys from the school St. Joseph des Carmes (near Fanjeaux, France) from where I was recently re-appointed to Post Falls, Idaho, spent five days in the traditional Benedictine monastery of Bellaigue, France. [At Our Lady of Guadalupe Monastery, Silver City, New Mexico, over 500 boys have made voluntary summer visits there since its foundation.—Ed.] There they took part in the Divine Office, helped the monks to bottle cider, and took walks with them. To take meals in a monastic refectory is the best way to teach youngsters table manners. The boys were given talks on the meaning of a monk's life totally consecrated to God. At St. Joseph des Carmes, senior high-school students have been studying the philosophy of St. Thomas. They were able to pray near his tomb in Toulouse and receive a special blessing with his relics in the chapel where his body stayed for one day. A sermon on the Angelic doctor was given, since it was his feast day.

The schools of the Society of Saint Pius X do their best to teach the classics as was done in Jesuit colleges. Another feature in our schools which we received from the Ignatian tradition is the Spiritual Exercises. Most schools have their juniors and seniors make a five-day silent retreat every year. This bears great fruit, especially in the domain of the formation of the will.

Pius XII gives us two guidelines in our task of strengthening the faith of our students:

The first: The faith of young people must be a praying faith. Youth must learn how to pray. Let this prayer be always in the measure and in the form, suitable to the age of youth, but it must ever be realized that, without prayer, it is impossible to remain firm in the faith.

The second: Youth must be proud of their faith, and ready to accept the fact that it will cost them something. From earliest childhood, the young must accustom themselves to make sacrifices for their faith, to walk before God with an upright conscience, and to reverence whatever He orders. Then youth will grow naturally, as it were, in the love of God. [Pope Pius XII, Allocution of April 18, 1952]

Several of the Society's schools utilize the "preventive system" of St. John Bosco. This shows that our priests are most desirous of learning from the experience of the educators whom the Church proposes to our imitation.

In May (2001), an interesting Latin seminar took place in Paris, France. It was presided over by Fr. Lorans, rector of the Society of St. Pius X's College in Paris. Christopher Brown from the United States gave an overview of the study of Latin through the history of Christendom. Hans Oerberg from Denmark explained the pedagogical principles behind his textbook, Lingua Latina per se Illustrata. Several professors from France also gave talks, but the one who "stole the show" was Professor Luigi Miraglia from Italy. He first gave us a wonderful conference in fluent Latin on his experience in teaching Latin according to his "natural method." He then brought "on stage" between 15 and 20 of his high school students who were in their second year of studying Latin with the Oerberg Method. He held a lesson for half an hour, asking questions in Latin and receiving answers in the same tongue about the texts they had studied. Two of Professor Miraglia's former students gave speeches in Latin, amazing everyone with their fluency and, most importantly, their love of Latin.

|

|

|

At this seminar, Professor Miraglia became acquainted with some of the Society of Saint Pius X priests present and scheduled a seminar like it in the United States for August 1-3 (2001) in Post Falls, Idaho. The U.S. seminar was attended by 45 people, half of them priests and faculty. As a consequence of it, schools like St. Joseph's Academy in Michigan have started to use the textbook Lingua Latina per se Illustrata. The basic principle of the method is not new, but follows the natural pattern of learning language. The text is so arranged that it enables the student to understand a new word or a new grammatical form from the context in which it occurs, much more after the manner by which he learns his own mother tongue. After using it several times in various contexts, its meaning becomes firmly fixed in the students' minds. Latin vocabulary and grammar are learned organically according to the same progressive approach by which any of us learn to speak. The advantage of this method is that it enables the student to understand the Latin text just by reading it attentively without having to engage in the usual mental gymnastics to translate it into English. Eventually, boys are able to think and speak exclusively in Latin.

This method of learning Latin as a living language is a return to a very ancient tradition as opposed to the methods of the past two or three centuries. The instructions given by Rome concerning the implementation of the apostolic constitution Veterum Sapientia (1962) requested that students in minor seminaries learn to speak Latin, not just translate it. Questions of the teacher and answers of the students were solely in Latin.

Professor Christopher Brown reported that the schools of Campos, Brazil—Bishop Castro de Mayer's former diocese—are planning to use the Oerberg textbooks. Fr. Couture of the Society of Saint Pius X's Asia District is using them to train his pre-seminarians. The collaboration between Society of Saint Pius X priests from different countries on matters of education can be very fruitful and we hope more communications of the kind manifested at the Post Falls meeting will be established in the future.

Several teachers wrote me to comment on the ideas I expressed in "Teach Me!" I would like to clarify one point. When I stressed the need of more active participation of the student in the class, I did not mean to exclude the authority of the teacher. As Dr. John Senior says: "The relation of student to teacher is not one of equality...It is the relation of disciple to master in which docility is an analogue of the love of man and God, from Whom all paternity in heaven and on earth derives."4

St. Thomas Aquinas explains very well the role of the teacher in an article of the Summa Theologica.5 The teacher exteriorly assists the intellect of the student in his discovery of truth, co-operating with God who enlightens the mind from within. Once again, the teacher cannot infuse knowledge in our mind, but he can lead us to knowledge because he possesses it. He knows the way and so he is able to give us some helps so that we too can acquire knowledge. Through skillful explanations, comparisons, and examples, he assists the student to grasp the truth, for instance, to see in a demonstration the connection between the premises and the conclusion. Because we need to engage the students in the process of learning if we want true education to take place, we have to develop what St. Thomas calls "studiousness" in order to spur in their minds a desire for knowledge. "This virtue," he says, "derives its praise from a certain keenness of interest in seeking knowledge of things."6 This is why it is necessary for teachers to awaken this "inquisitiveness" in their pupils. This yearning for the truth is one of the conditions of learning.

A five-day session for Society priests working in our European boys' schools is planned for July (2002) in Flavigny, France. In the same way as the traditional Dominican Sisters meet several times a year to co-ordinate their efforts in education and assure unity in the schools of their congregation, the European priests of the Society of Saint Pius X will meet. Young priests will learn from their more experienced confreres; laymen experienced in the field of education could give conferences; problems could be discussed and solutions adopted. For a long time, priests have expressed a need for such sessions.

Our schools have to form Catholic men for the 21st century, and the conditions of life in this century are vastly different from those in the centuries of St. Benedict, St. Dominic, or St. Ignatius. We live in our apostate world, a world which has received the Catholic Faith and rejected it. The devil has made such a mess of everything on earth that the world is slowly becoming uninhabitable for anybody but saints. In other centuries, men of average virtue could fulfill their destiny here below without being obliged to heroism. In the 21st century, however, Satan has appeared to have organized everything for the eternal damnation of the larger number of souls. It is no longer possible to remain lukewarm and still save our soul. More than ever, mediocrity is not a viable option. Our boys must become Catholic warriors or perish. How can we develop this fighting spirit in our students? This is one of the questions which will be discussed during this Flavigny meeting, along with others regarding curriculum, formation of teachers, vocations, etc. We entrust the preparation of this session to your prayers. As Pope Pius XII reminded us in a fiery speech to young people:

A call to rebirth and a cry for recovery sounds throughout the world: it will be a Christian recovery. As We said in the beginning, you want a new structure to arise from the ruins heaped up by those who preferred error to truth. The world will have to be rebuilt in Jesus.

Young people! do you want to co-operate in the gigantic enterprise of reconstruction? The victory will be Christ's. Do you want to fight with Him? To suffer with Him?Do not, then, be weak and lazy. Rather, be inflamed and ardent youths. Enkindle the fire which Jesus came to bring into the world and make it blaze up! (Pope Pius XII, Allocution, March 24, 1957)

Immaculate Heart of Mary, pray for us.

Fr. Hervé de la Tour was ordained in 1981 by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre and immediately assigned to teach at St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary (then in Ridgefield, Connecticut). From 1982-89 he was rector and headmaster at St. Mary's College & Academy, Kansas. For the period 1989-96 he was assigned as professor at Holy Cross Seminary, Goulburn, Australia, and then to St. Anthony's Priory (1996-2000) in New Zealand. Recently, he was reappointed from St. Michel de Carmes Boys' School, Montreal-Sur-L'Aude in southern France, to Immaculate Conception Priory, Post Falls, Idaho.

1. Fr. Roger-Thomas Calmel, O.P. (1914-1975), a prominent French Dominican and Thomist philosopher, made an immense contribution to the fight for Catholic Tradition through his writings and conferences. His most enduring influence is through the traditional Dominican Teaching Sisters of Fanjeaux and Brignole (France) who operate 12 girls' schools in France and the United States. Before Vatican II, Fr. Calmel formed the founding members of these communities, specifically giving them the philosophical and pedagogical principles to educate Catholic girls in a de-christianized, secular and modernist environment. With the outbreak of the current crisis in the Church, these nuns, thanks to Fr. Calmel, were already well prepared.

2. Divini Illius Magistri (Kansas City, MO: Angelus Press, 2000), p. 54.

3. Ibid., p. 57.

4. Restoration of Christian Culture, p. 155.

5. ST, Q. I, Art. l, ad 1, corpus.

6. ST, II-II, Q. 167, Art. 2, ad 3.