Forward to Benedict

Louis B. Ward

Introduction

There is so much talk these days about restoration in the Church and of a Catholic society that we rarely consider how Christendom was established in the first place. The answer is very simple—monks. Monks following the Rule of St. Benedict to be precise. It may be a simplification, but any student of history knows that the monasteries were the primary Christianizing and civilizing influence on a pagan (at best Arian) Europe. Dom Gueranger said, "The Order of Saint Benedict is the great fact of Western Christianity, because its influences have acted, through the centuries, upon religious and political society, and because the diverse religious families which have succeeded one another for eight centuries stem from it, or are founded on its traditions" (Solesmes and Dom Gueranger, by Dom Louis Soltner, p. 205).

We must not have an incorrect notion of how monasticism affects society. It is certainly not by striving to implement a political program. No, the means are entirely supernatural. The weapons are, by the grace of God, prayer, Faith, Hope and Charity. It is as Our Lord promised, "Seek first the kingdom of God and His justice, and all these things shall be given you besides" (Mt. 6:33).

Dom Gueranger said, "What then is monasticism, this grand thing which the ancient world bore within itself and which, if we believe the Fathers, seems to have harvested the excellent fruit of Christianity? It is the state in which man, raised from the original fall by Jesus Christ, works to re-establish himself in the image of God by virtually separating himself from all that can cause sin" (Ibid., p. 206). The monasticism that will solve social problems is that which aims primarily at the reformation of the individual. Without holiness, nothing... with holiness, everything.

"Prepared by God Himself, full of God, the monk will be productive, with a productivity that cannot be compared to that of others. This love of brethren, of the Church, that inspires his prayers, his work, his penance in the cloister, will overflow into human society, and history will judge the degree of life which the Church attains in any given century in proportion to the esteem rendered the religious state, the number of its representatives, and what they do" (Ibid., p. 208).

Not only will it be the example of the monks, but their constant prayer and sacrifices. The Angelus has recently treated of this aspect of the monks' work in the May 2001 issue. In this issue and next, we wish to address the power of the monks' example and apostolate. —The Angelus

Today in every nation thinking men recognize that our boasted civilization approaches the brink of ruin. Happily there is no need to go to the politician, the economist or the superficial student of political science or sociology for an analysis of the present day problem.

For the past 120 years, the Papal encyclicals have analyzed the problem of what is wrong in the world. Those encyclicals have been written for the whole world, not for the United States or for any other nation alone, but for the four and a half billion or so people who live in the world. Nor have those encyclicals concerned themselves only with the diseases of civilization. They have pointed out the remedy in all detail and application.

Pope Leo XIII

The great Leo XIII, in the encyclical Inscrutabili published April 21, 1878, first analyzed the evils affecting modern society. Leo pointed to the obstinacy of mind, which brooked no authority however lawful. He told us then that we were rushing wildly along the straight road to destruction.

He recalled the ages of faith, the culture of Christian times and contrasted modern society with those ages. He discussed charity as it existed since the dissolution of religious bodies and since the growth of public institutions wholly without the control of the Church. He traced the history of civilization in the spreading of truth amongst savage and superstitious people, in the elimination of slavery and serfdom, in the restoration of men to the original dignity of their nature, in the introduction of sciences and arts and in the founding of charitable institutions.

|

|

In 1878 Pope Leo told the world that the very notion of civilization is a mere fiction, if it rest not on the abiding principles of virtue and justice. Leo termed the present civilization, "a worthless imitation and a meaningless name, never possessing either true or solid blessings." Then he emphasized the necessity of forming domestic society in the mold of Christian life through the family.

In the same year, Leo XIII wrote another encyclical, Quod Apostolici Muneris, in which he criticized the present era in its subversion of the supernatural order, the enthronement of unaided reason, the eagerness to outstrip others, the organization of government without God and the withdrawal of religion from the scheme of studies at university, college and high school. Leo told the world frankly that men of lowly condition, heartsick of a humble home or poor workshop, with God removed from their lives, fix eager eyes upon the abodes and fortunes of the wealthy.

In his early utterances on social justice, Leo laid the rich under command to give of their superfluity to the poor under the penalty of eternal punishment and to succor the wants of the needy. In this encyclical, Leo pleaded for the poor and the building of homes and refuges where the poor and afflicted could be received, nurtured and tended.

Leo saw the world sinking with the years, crushed with its weight of ills and charged his generation to go to work for the regeneration of human society, reminding it that such work had every promise of success. "For the hand of the Lord is not shortened, that it cannot save, neither is His ear heavy, that it cannot hear" (Is. 59:1).

Two years later, in 1880, Leo XIII wrote Arcanum Divinae, in which he explained that the benefits which come from the supernatural order of grace are paralleled by fruits bestowed abundantly in the order of nature. In this remarkable encyclical Leo records that the Christian order was once established in the world and that men learned what Providence was and learned to dwell in it habitually. He outlined the benefits that accrued to men, to families and to states. He explained that fortitude, self-control, constancy and the evenness of a peaceful mind, together with high virtues and noble deeds were fostered.

He recalled how rulers became just and were revered by their people, how obedience of the subject became ready and unforced, how the union of citizens became closer and the rights of property more secure. In this encyclical Leo tells us that if the Christian order were designed for the temporal only, it could not have been improved upon.

Five years later, in 1885, Leo XIII gave the world his fourth great encyclical on the social order: Immortale Dei. In it he characterizes the relationship of the Church as a civilizing influence among nations, in the following remarkable paragraph:

And in truth, wherever the Church has set her foot, she has straightway changed the face of things, and has tempered the moral tone of the people with a new civilization, and with virtues before unknown. All nations which have yielded to her sway have become eminent for their culture, their sense of justice, and the glory of their high deeds.

Not content with tributes to past glories, Leo tells the world plainly that it is not difficult to determine what would be the form and character of the state today were it governed according to the principles of Christian philosophy. It is Leo XIII who is the apostle of the abundant life, telling us that Christ came into the world that men "might have life and have it more abundantly" (Jn. 10:10), that history witnesses religion subduing barbarous nations, changing them from a savage to a civilized condition, bestowing on the world the gift of true liberty and most wisely founding numerous institutions for the solace of human suffering.

In 1888, on Christmas day, Leo XIII gave the world a fifth encyclical Exeunte jam Anno. Recognizing the growth of rationalism, materialism, and atheism, Leo sees the fruits of socialism, communism and nihilism. Once more he explains the duty of men "to run to the fight proposed to us" armed and prepared with the same courage and the same weapons as Christ had. Leo's remedy is a Christian rule of life and he recommends self-denial, prayer and good works as the surest ways to secure the general welfare.

In 1890, in his sixth encyclical, Sapientiae Christianae, Leo condemns the false prudence of the pussyfooting Christian as criminal excess. He castigates the cowards of the world, the hypocrites who mourn over the loss of faith and the perversion of morals, and yet never trouble themselves to bring any remedy, but rather intensify the mischief through forbearance and harmful dissembling. Such false prudence Leo characterizes in the language of St. Paul, "Wisdom of the flesh and the death of the soul" (Rom. 8:6).

Leo explains clearly that the enemies of the faith are conscious of a multitude of fainthearted Christians who are leading the lives of cowards, untouched in the fight. He also castigates false zeal and rashness on the part of those who spend their energies in fruitless contention.

In this encyclical, Leo calls for soldiers to attack the enemies of Christ with extreme daring, without tiring, under obedience, with courage, deficient in nothing. "Such," says Leo, is "the wisdom of the spirit" (Rom. 8:6).

On May 15, 1891, Leo XIII presented the greatest of his encyclicals on the social problem. This was the famed Rerum Novarum, in which he analyzes the social problem and demands an opportune remedy. He portrays the working man surrendered, isolated and helpless in the face of the hardheartedness of employers and the greed of unchecked competition. He attributes to rapacious usury the increase of misery and reminds the world that once the Church condemned usury as practiced by covetous and grasping men. He points out that the hiring of labor and the conduct of trade are concentrated into the hands of the few, "so that a small number of very rich men have been able to lay upon the teeming masses of the laboring poor a yoke little better than slavery itself."

He tells the rich that their wealth is of no avail for eternal happiness, but rather that riches are obstacles, that the rich should tremble at the threatenings of Jesus Christ—threatenings so unwonted in the mouth of our Lord—and that most strict account must be given to the Supreme Judge for all we possess. He distinguishes the right of ownership and the use of private property and he teaches the world that property must be shared without hesitation when others are in need.

Again he recalls the ages of faith, where civil society was renovated by the teachings of Christianity, when the human race was lifted up to better things and brought back from death to life: "When society is perishing, the wholesome advice to give to those who would restore it is to call it to the principles from which it sprang; to fall away from its primal constitution implies disease; to go back to it, recovery."

Again Leo reiterates that Christian morality, when practiced completely, leads to temporal prosperity and that as it was done in the past, it may be done again.

Age gives way to age, but the events of one century are wonderfully like those of another. Once those destitute of wealth and influence won to their side the favor of the rich and the good will of the powerful, they showed themselves industrious, hard working, assiduous and peaceful, ruled by justice and bound together by brotherly love. In the presence of such a mode of life and such example, prejudice gave way, the tongue of malevolence was silenced, and the lying legends of ancient superstition little by little yielded to Christian truth.

In this same encyclical Leo gave utterance to language unparalleled in the present day, as he frankly states: "Since religion alone can avail to destroy the evil at its root, all men should rest persuaded that the main thing needed is to return to real Christianity, apart from which all the plans and devices of the wisest will prove of little avail."

Pope St. Pius X

Following Leo XIII came Pope Pius X, who in 1903 wrote Fin dalla Prima, his encyclical letter on Christian social action. Pius X distinguishes justice from charity, reaffirmed the rights of the working man, the obligations upon the rich and warns the rich to be ready in the day of judgment to give a special account of their trusteeship. He encourages the poor not to blush in their poverty and he demands mutual contributions from both capitalist and laborer in the solution of the labor question and calls for organizations for timely aid for those in need.

On June 11, 1905, Pius X issued his second encyclical on the social question entitled Il Fermo Proposito. In it he emphasized the work of the Church as a civilizing influence, preserving the good in the ancient pagan civilization, rescuing the barbarian and implanting upon the whole of human society the stamp of Christian civilization.

Reiterating the oft-repeated doctrine of Leo XIII, Pius X says that it is unnecessary to say what prosperity and happiness, peace and concord, what respectful submission to authority and what excellent government would be established and maintained in the world if the perfect ideal of Christian civilization could be everywhere realized.

The world-renowned thesis of Pius X was to restore all things in Christ—Instaurare omnia in Christo (Eph. 1:10). He would reinstate Christ in the family, the school and society. He would have civil authority take up the problems of the working and agricultural classes, dry their tears, soothe their suffering, improve their economic condition and make laws conformable to justice.

He calls the clergy to action and tells them they should be moved with compassion, "seeing the multitudes distressed, lying like sheep that have no shepherd." He asks all to strive, through the press, through speech, through direct help, to ameliorate the economic condition of the people and begs for support of institutions dedicated to this end.

He speaks of the futility in pointing out what good can be done unless it can be put into practice and that the thing done must be done in the name of Christ if it is to be successful.

|

When society is perishing, the wholesome advice to give to those who would restore it is to call it to the principles from which it sprang: to fall away from its primal constitution implies disease: to go back to it, recovery....Since religion alone can avail to destroy the evil at its root, all men should rest persuaded that the main thing needed is to return to real Christianity, apart from which all the plans and devices fo the wisest will prove of little avail.—Pope Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum |

Benedict XV

At the outbreak of the First World War in November 1914, Benedict XV, in his Encyclical Ad Beatissimi, warned the world that "unless God soon comes to our help the end of civilization would seem to be at hand." Benedict XV noted the absence of mutual love, the contempt in which rulers were held, the rank injustice between the classes of society and the striving for transient and perishable things, as the four great causes of the breakdown of civilization.

Pope Pius XI

The first Encyclical of Pius XI, Ubi Arcano Dei, was written in December 1922. Pius XI is commenting on the troubles left by the war. He tells the world that the Treaty of Versailles was written in the public documents and not in the hearts of men, that man is still a stranger and an enemy to his fellow man, that force and numbers alone count, that the habit of ill-will has become natural to many, that men strive to overcome one another solely to get possession of the good things of life, that this striving for material things brings every sort of evil, moral abasement and dissension.

Pius XI comments on the intemperance of desire under the appearance of public good, of love of country, as the source of rivalry and hatred among nations. He states that God has been removed from the conduct of public affairs, that authority is believed to be derived from men and not from God, and that the foundations of authority have been swept away. The Pope demands Christian peace, the guardian of order and the example of Christ followed in public and private life as remedies for the hatred among nations.

On May 15, 1931, Pius XI issued Quadragesima Anno, on the reconstruction of the social order. It analyzed a world divided into two classes. The first class was the rich, enjoying the comforts that concentrated wealth had brought. It was a small group perfectly satisfied with its position. And he saw another class consisting of the masses of men reduced to dire poverty. Pius XI saw the causes of decay as the open violation of justice. He found labor forced into the excesses of socialism and communism and he found the world leaderless, with everyone convinced that things were out of harmony with the plans of the Creator, with men not knowing which way to turn.

Pius paid great tribute to his predecessor Leo XIII. He reviewed his teachings and spoke of how the world regarded them as novel and with what suspicion they were judged by some and what great offense they gave to others. He told of how they were received by the "slow-of-heart" who ridiculed the social philosophy of the Church and how timid souls feared to scale the lofty heights of Leo's teachings. To others Leo was dealing with vain Utopian ideals desirable rather than attainable in practice.

Pius brilliantly reviewed Leo's doctrine on the reform of Christian morals, with the Gospel as the guide. Pius tells us that his predecessor would enlighten the mind and direct it by precepts, that Leo was organizing a Christian social science founded on instruction, beneficence and charity.

Pius reviewed the teachings of Leo on private property, its individual and social character, the obligations of ownership, the power and limitations of the state in regard to property, the obligation of the wealthy respecting superfluous income, the relationship of labor and capital and the right distribution of the profits of production.

After paying tribute to these teachings of Leo, Pius XI says:

Prosperous institutions organically linked with each other, have been damaged and all but ruined, leaving thus virtually only individuals and the state. Social life lost entirely its organic form. The state, which now was encumbered with all the burdens once borne by associations rendered extinct by it, was in consequence submerged and overwhelmed by an infinity of affairs and duties.

In commenting on the state, Pius tells us that it is wrong for the state to arrogate to itself functions which can be performed efficiently by smaller and lower bodies. This is a fundamental principle of social philosophy called subsidiarity. It retains its full truth today.

Pius XI says the proper order of economic affairs cannot be left to free competition alone. More lofty and noble principles must be sought in social justice and social charity. This justice must be truly operative. It must build up a juridical and social order.

In the 40 years that had elapsed between Leo XIII's Rerum Novarum and Quadragesima Anno, Pius XI found many changes. He found not only wealth accumulated in the hands of the few but immense power and despotic economic domination in the hands of not the owners but the trustees and directors of invested funds, who administer them at their own good pleasure.

He found a few men holding and controlling economic power and likewise governing and determining its allotment (credit) so that they hold the life blood of the entire economic body in their hands and the very soul of production "so no man dare breathe against their will."

He characterized the modern accumulation of power as the result of limitless free competition, permitting the survival of those who are the strongest, those who fight most relentlessly, who pay least heed to the dictates of conscience. He says this concentration of power has led to a three-fold struggle for domination. First, within the economic sphere; second, for the control of the state; and third, the clash between nations.

In 1931, economic life had become hard, cruel and relentless in a ghastly measure. On the one hand, the world witnessed economic nationalism or economic imperialism. On the other, internationalism or socialist ideological imperialism.

Thus in our day there is in one part of the world merciless class warfare: economic liberalism or capitalism; and in another part of the world, a complete abolition of private ownership and the hatred of God, as witnessed in communism.

With this analysis in mind, Pope Pius XI turns to the remedy. Once more we are told that economic life must be inspired by Christian principles, that God must be placed as the first and supreme end of all created activity, that material goods must be regarded as mere instruments under God, that those engaged in production must have a profit, that the law of charity must operate, but that it cannot take the place of justice unfairly withheld; that the spirit of Christian moderation must be diffused and that students of social problems must spare no labor and be overcome by no difficulty, but daily take more courage.

Pius XI demands that we leave no stone unturned to avert these grave misfortunes from human society. He points to the communist as he cunningly selects and trains resolute disciples, who spread their false doctrines daily more widely amongst men of every station and clime. He sees the communists laying aside internal quarrels to link up harmoniously into a single battle-line and strive with united forces towards this common aim. He observes that Catholic activity loses effectiveness by being directed into too many different channels and he calls upon his followers to unify to recivilize the world.

(continued below)

Pope Pius XII on St. Benedict

From these norms and axioms which it has pleased Us to cull from the Benedictine law, there can be easily discerned and appreciated the prudence of the monastic rule, its opportuneness, its wonderful harmony and suitability to human nature, as also its significance and supreme importance. During a dark and turbulent age, when agriculture, honorable crafts, the study of the fine arts profane and divine were little esteemed and shamefully neglected by nearly all, there arose in Benedictine monasteries an almost countless multitude of farmers, craftsmen and learned people who did their utmost to conserve the memorials of ancient learning and brought back nations both old and new—often at war with each other—to peace, harmony and earnest work. From renascent barbarism, from destruction and ruin they happily led them back to benign influence human and Christian, to patient labor, to the light of truth, to a civilization renewed in wisdom and charity.

In like manner it can be asserted that the Benedictine Institute and its flourishing monasteries were raised up not without divine guidance and assistance, in order that, while the Roman Empire was tottering, and barbarous tribes goaded by warlike fury were attacking on all sides, Christian civilization might make good its losses and after civilizing nations by the truth and charity of the Gospels would lead them skillfully and tirelessly to fraternal harmony, fruitful labor and to a virtuous life ruled by the precepts of Our Redeemer and guided by His grace. Just as in past ages the Roman legions, which tried to subdue all nations to the imperial mother city, marched along the roads built by the consuls, so now countless bands of monks whose arms "are not carnal but mighty to God" are sent by the Supreme Pontiff to extend to the ends of the earth the peaceful kingdom of Jesus Christ, not with sword or violence or slaughter but with the cross and the plough, with truth and charity. Wherever these unarmed bands composed of heralds of the Christian religion, of workmen, of farmers and teachers of sciences human and divine passed by, there forests and untilled lands yielded to the plough; centers of craftsmen and fine arts sprung up; from an uncouth and wild life men conformed to civil society and culture. For them the teaching and the power of the Gospel was the light that ever led them on. Numerous Apostles, burning with divine charity, traversed unknown and restless regions of Europe which they generously watered with sweat and blood; appeasing the populations they lighted for them the torch of Catholic truth and holiness. It may then be asserted that although Rome by many victories extended the might of her empire on land and sea, still "her warlike conquest subjugated fewer than the Christian peace conquered."

If these norms, in virtue of which Benedict once illumined, saved and built up the society of those turbulent times which was crumbling and even led it back to better ways, be accepted and honored universally today, then no doubt our age will be able to come safe from its terrifying shipwreck, make up its losses material and spiritual and adequately remedy its deep wounds. [Extracts from Pope Pius Xll's Encyclical Fulgens Radiatur (On St. Benedict)]

The World Before Benedict

No man can read these encyclicals carefully without finding in them a profound cause for hope that reform in our social and economic life, true and permanent prosperity and peace among the nations are within our grasp, if we only heed the lessons of history. Even a superficial survey of nineteen centuries will indicate the tremendous factors evident in the story of civilization.

Christ's last words addressed to the Apostles before He ascended into heaven were, "You shall be witnesses unto Me in Jerusalem and in Judea and Samaria and even to the uttermost parts of the earth" (Acts 1:8). After the descent of the Holy Ghost, eleven of the Apostles struck out for the missionary field to the uttermost bounds of the earth, to preach the Gospel to all mankind. One, James the Lesser, remained in Jerusalem to guide the infant church.

In the earliest days, conversions were most encouraging. The book of Acts records Peter's sermon converting 3,000 Jews (Acts 2:14-41). Step by step the faith was brought to the people of the Mediterranean. Those early conversions reflected the Divinity of Christ, the unrivalled doctrine which He taught, the apostolic zeal of the early missionary and the good example of the early Christians, so that the pagan could point and say: "See how these Christians love one another, and how they are ready to die one for the other." Even Julian the Apostate praised the charity of the Christians, the sanctity of their lives and their good works. The world today records their heroic sacrifices. Tertullian enunciated the principle: "Semen est sanguis Christianorum" (the seed is the blood of Christians).

In those first five centuries, the East witnessed the rise of asceticism. It had produced such monks as St. Anthony, St. Paul the first hermit, St. Pachomius, the two Ammons, the monks of Sinai, Hilarion in Palestine, St. Ephrem in Mesopotamia, St. Simon Stylites in Syria, St. Basil and St. Gregory in Cappadocia, St. John Chrysostom in Constantinople, St. Theodosius at Antioch and countless others familiar to every student of history.

The fifth century witnessed the rise of Irish monasticism. St. Patrick, apostle to Ireland, in his work of converting that historic isle, had founded a monastery at Armagh. It was followed by those of St. Finian at Clonard, St. Brendan at Clonfert, St. Cumgall at Bangor, St. Kiernan at Clonmacnoise, St. Enda at Arran, St. Carthage at Eismore and St. Kevin at Glendalough. Greatest of all the Irish monks was Columbanus, who in honor of the Apostles founded his "mission of the twelve," twelve who were to leave each year for the spiritual conquest of Europe.

History records Columba in Scotland, Aiden in England, Gall in Switzerland, Friedolin on the Rhine, Fiacre at Meaux, Kilian at Wurzburg, Fursey on the, Marne and Catuldus in Southern Italy.

No rational mind minimizes the importance of those first five centuries. The zeal of the Apostles and missionaries had introduced the faith to all the nations on the Mediterranean and had planted it in Ireland, Britain, Gaul, Spain, Germany, Persia, Armenia, Arabia, Abyssinia and Nubia. Among the barbarian tribes converts were made among the Visigoths, the Ostrogoths, the Lombards, Burgundians, Vandals and Franks.

The Church had, of course, accepted the slave as well as the freeman. The manumission of the slave was recognized as a work of mercy. A moral bond had largely superseded the legal bond as slave and freeman were subjected to the same restraints of moral law. In the field of justice, branding on the forehead had been done away with, crucifixion had been abolished, the right of sanctuary had been established and suicide, a declared virtue under certain pagan teachings, was condemned. Abortion and exposure of infants were legal murder. Gladiatorial games, though still conducted in the arena, claimed no longer innocent victims sacrificed for a sporting populace. Everywhere the Christian teaching of the value of human life imprinted itself even on the minds of pagans. Their own temples best testify to the acceptance of the moral law. Those temples were no longer halls of open infamy. The festival orgies of other days were moderated by Christian example. Julian the Apostate gave grudging testimony as he attempted to introduce into pagan life Christian social ideas and principles.

|

|

|

The World at the Coming of Benedict

At the end of the first five centuries, much had been accomplished. The heroic stories of the martyrdom of the early Christians are still read by Catholics today. Yet those ages have other stories of the great monks who had given the personal example of lives of self-abnegation, austerity, poverty, erudition, oratory and scholarship; all for the edification of a pagan world. No student of history discounts their sanctity, their simplicity or their imitation of Christ.

Yet never was the world in a more deplorable condition than it was at the end of those first five centuries. All historians portray the confusion, the corruption and despair. In morals, in law, in science and in art all was in ruin. The followers of Christianity were hopelessly divided by heresy and throughout the whole Roman Empire there was not an emperor, king, prince or ruler who was not a pagan, Arian or a Eutychian.

Italy had been ravished by Alaric and Attila. In the east Basilicus had appointed 500 bishops to dispute with Rome in the year 476. Also in the east, Zeno had fathered heresy in the "Edict of Union" published in 482, against the Council of Chalcedon. Odoacer, chief of the tribe of Herules, had snatched from the shoulders of Romulus Augustulus the imperial purple of the Caesars.

In the forty-two years that followed from this fall of Rome in 476 to the ascension of Pope Justus I, in 518, the historian finds the four worst decades of civilization. Not a state of Europe belonged to the Catholic faith. Britain was pagan, Germany was pagan, Gaul was overrun by the pagan Franks on the north and on the south by the Arian Burgundians. Spain was devastated by the Visigoths, Sueves, Alans and Vandals. North Africa had been laid desolate by the Vandals and was suffering a persecution more vicious and terrible than that at Rome.

Outside the Roman Empire was Ireland alone, under the apostle Patrick, Christianized from king to serf.

The end of five centuries of Christianity witnessed civilization at its lowest ebb. Without an understanding of this fact no man can understand the centuries which followed. In the midst of darkness one candle burned. That candle was St. Benedict who unwittingly was to regenerate the western world.

|

|

The main thrust of Benedictine life is the liturgy and its influence on society, the way of life lived around it, being the model of Catholic society. —Rev. Fr. Dom Cyprian, O.S.B. |

St. Benedict of Nursia

Benedict was born in the city of Nursia in the year 480; four years after Odoacer, the barbarian chief, had technically ended the long life of the Roman Empire in the West (it continued until A.D. 1453 in the East). Benedict was a Catholic and a Roman citizen brought up under a barbarian Arian regime. Having been sent to school at Rome at the age of 14, he fled the vices and temptations of that city, accompanied by his nurse, Cyrilla.

They settled in Enfide, a small town of pious inhabitants not far from Rome. Here Benedict was able to relax, pray and study. But before long, he became known for performing a miracle and again his soul was troubled. He fled alone into the surrounding wilderness to be a hermit. There he met Romanus, a monk of a nearby monastery, who clothed Benedict with the animal skin monastic habit (melotte) used at that time and helped Benedict in his solitary spiritual combat by settling him into a cave near a waterfall on the Anio river, some 50 miles from Rome at Sublaqueum (below the lake), modern day Subiaco.

For three years Romanus brought food to Benedict as he lived in the cave near the villa where the Emperor Nero, four centuries before, had carried on his pagan orgies. The ruins of Nero's villa can still be seen at Subiaco along with Benedict's cave, the Sacro Speco, and his monastery.

As in the case of many an ascetic, the good name of a holy man attracted visitors, and after three years of solitary life, Benedict was besieged by patrician and barbarian alike. Benedict finally left his cave at the request of neighboring monks to take charge of a small monastery at Vicovaro. This proved disastrous, as Benedict knew it would, because of the dissolute life of these monks. Benedict proceeded to found 12 monasteries in the Anio valley, only to be forced to leave some years later by the machinations of a jealous local priest.

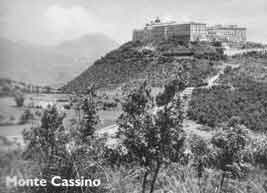

Benedict went on to found the monastery of Monte Cassino on a high, rugged and desolate hill overlooking the Valley of the Liris. At Monte Cassino, he destroyed the altar to Apollo, led the neighboring peoples from paganism to the Catholic Faith, cultivated the arid lands of the mountain, cleared the fertile fields below, built a monastery and oratories, practiced hospitality and perfected the Rule, which was to be a path of sanctity for millions and consequently the basis of the regeneration of the western world.

The history of his famous monastery shows that it was destroyed by the Lombards in 583, restored by Gregory in 731, destroyed by the Saracens in 857, rebuilt by the Abbot Aloguin in 950, again destroyed in the 11th century, rebuilt by Pope Benedict XIII in 1727, destroyed by the wars and revolutions of Italy, restored by Joseph Bonaparte as a library in 1805 and finally re-established as a monastery in the last century. Monte Cassino was again completely destroyed by the United States Air Force during World War II. (Interestingly, all was destroyed except the tomb of Sts. Benedict and Scholastica as the bomb that hit it failed to detonate.) It was rebuilt under Popes Pius XII, John XXIII, and Paul VI.

At the height of its power, Monte Cassino numbered in its jurisdiction two principalities, four bishoprics, 20 counties, 250 castles, 336 manors, 440 towns and 1,662 churches. It controlled 23 maritime ports, 33 islands and over 200 mills. In the 15th century its income has been estimated, in terms of present monetary standards (1997 dollars), at $210,000,000 per year. Benedict of Nursia never dreamed of the future of Monte Cassino. Nor did he dream of the influence he would wield in the history of civilization.

The Rule of St. Benedict

That Benedict was writing the Rule for the whole world is indicated by the internal evidence of the Rule itself. Certainly it covered many monasteries in many climates and embraced a full recognition that there were many types of monks in that day, from the holy ascetics in the East down to those wandering beggars in monastic garb little distinguished from vagrants who walked from town to town demanding hospitality and seemingly reflecting nothing in the spiritual life:

Fourth and finally, there are the monks called gyrovagues, who spend their entire lives drifting from region to region, staying as guests for three or four days in different monasteries. Always on the move, they never settle down, and are slaves to their own wills and gross appetites. In every way they are worse than the sarabaites.It is better to keep silent than to speak of all these and their disgraceful way of life. Let us pass by, then, and with the help of the Lord, proceed to draw up a plan for the strong kind, the cenobites [monks who live in community] (RB 1:1-13).

Benedict was fitted to write the Rule, for he was thoroughly conversant with Eastern monastic literature as represented by St. Anthony of the Desert, down through Jerome, Augustine, Basil, Cassian, Pachomius, Rufinus and others. He also inherited the Roman tradition of authority, organization and law. This background enabled him to perfectly synchronize sublime spiritual truths with the need to codify monastic discipline so that as many monks as possible could scale the spiritual heights.

As Benedict considered a rule for many monasteries, he undoubtedly had no idea either that the Rule would bear his name or would be the guide to thousands of monastic houses to be known throughout the centuries as "Benedictine." Benedict knew monks and he produced a Rule both practical and moderate, a "minimum rule written for beginners" (RB 73:8). It was, likewise, so wise, and so holy that it would lead men to perfection.

Conscious that the monastic garb alone did not separate monks from the world, Benedict emphasized the enclosure, not only to secure that separation but to make emphatic the tie between the individual monk and his own monastery. To secure that separation from the world, Benedict provided that the monastery be economically self-sufficing. From agriculture it was to take its food and fibre; from native rock or clay it was to quarry the stone or make the bricks to provide shelter; from the available timber and neighboring mines it was to take the raw material to be fabricated by the industrial arts of wood carving, cabinet making, the working in iron, in brass and precious metals. In church building as well as the monastic appendages, architecture was called into play. Thus labor was provided which was always useful labor, never an end unto itself.

In the Rule of Benedict the monks, with the Abbot, were to constitute the family. Benedict reviewed the centuries of asceticism and found in individualism only a qualified imprint on human society.

The Rule recognizes that the world consists of many nations speaking many languages with a multitude of traditions, laws and cultures, with classes of human society from emperor through aristocracy, magistrates, tradesmen down to the lowest serf or slave. Benedict recognized that the unit of human society was the family and that in the family was the common denominator of all nations, peoples, tribes, traditions, laws and customs. It made no difference what race, what nation, what climate or what status of civilization, the family was the unit of human society and the common denominator of all.

The Church could not make a social impact upon civilization were the vehicle mere individualism. Nor could nationalism answer the problem of world conversion. The individual gifts of self-abnegation and humility of Simon Stylites, or Augustine or Basil or St. Anthony of the Desert simply could not be duplicated in the lives of the two hundred millions of individuals who awaited within the ruins of the western Roman Empire the Christianizing and civilizing influence of the Catholic Church.

Benedict found this common denominator among the peoples of the world in the human family. The monks became, under the Benedictine Rule, a family, with the Abbot as father (cf. RB 2). This father was regarded as the representative of Christ. His spiritual sons worked with him for spiritual perfection. They were to produce by manual labor that wealth which would provide for themselves a sufficiency and for the poor a surplus. All over and above necessity belonged to the poor.

Throughout the entire Rule, the relation between the natural and the supernatural is apparent. Throughout the whole Rule moderation, in contrast to spiritual calisthenics, is apparent.

Benedict recognized that the reform of morals and society must have a social approach, because it is a social problem. So he patterned the monastic life on the permanency of family life and he patterned his family life on the virtues of the Gospels. The Rule epitomizes the Gospels and sets up a norm which was practical and possible for millions to follow.

But man is not purely social. He is an individual called to participate in the community. Thus St. Benedict address individual men:

Listen, my son, to your master's precepts, and incline the ear of your heart. Receive willingly and carry out effectively your loving father's advice, that by the labor of obedience you may return to Him from whom you had departed by the sloth of disobedience.To you, therefore, my words are now addressed, whoever you may be, who are renouncing your own will to do battle under the Lord Christ, the true King, and are taking up the strong, bright weapons of obedience (RB Prol:l-3).

Benedict emphasized three things: poverty, obedience and humility. Chastity was unmentioned, because it was assumed in the very concept of monasticism. The Divine Office was the rock upon which all was based. Benedict called the Divine Office the work of God and ruled that nothing was to be preferred to it (cf. RB 43:3).

Poverty

The monks were to dwell in poverty, because poverty excluded worldliness. Upon entering the monastery, the monk gave up all his property and cut himself off from his patrimony (cf. RB 58:24-26). From that time on he owned personally no property whatsoever. He was to be shut off from the world, because Christ had taught: "If any man love the world, the charity of the Father is not in him" (I Jn. 2:15).

Obedience

Obedience to Abbots who operated under law was merely a reflection of the Divine Life. The Abbot, elected by the monks themselves, ruled not only under the law of the Rule but under the law of God. The Abbot held the place of Christ in the monastery. He was the father of a family; hence he was entitled to obedience. To the monk it was Christ at the head of the table and to the ones who understood Christianity happiness was found in obedience, not in independence.

Under obedience, the monks obeyed not only their Abbot, but each other as well: "Obedience is a blessing to be shown to all, not only to the abbot but also to one another as brothers, since we know that it is by this way of obedience that we go to God. Therefore, although orders of the abbot or of the priors appointed by him take precedence and no unofficial order may supersede them, in every other instance younger monks should obey their seniors with all love and concern" (RB 71:1-4).

Christ said to his disciples, "My yoke is sweet, and My burden light" (Mt. 11:30). But the devil said, "The path of perfection is all thorns." Obedience was emphasized by Benedict in the prologue to the Rule: "That thou mayest return by the labor of obedience to Him from Whom thou hast departed by the sloth of disobedience" (RB Prologue:2). Under the Rule, submission must be prompt, perfect and absolute. It is by perfect obedience, more than by extreme asceticism, that the monk is to conform himself to the will of God.

Humility

Humility comes from the Latin humus, a word that we have in English that refers to the component of soil that consists of decaying organic matter. It is not dirt, but that part of the soil which gives life. Humility serves the same place in the spiritual life. It is where love of self decays and gives way to love of God, true charity. Just as plants must grow in soil with lots of humus (that's why we put compost on our gardens), so virtues will not grow in a soul that is not pervaded with humility. Humility is the absolute rock-bottom necessary element of the spiritual life. Benedict made it the heart of monastic asceticism.

Humility is crucial for our individual spiritual lives. Holy Scripture says, "for everyone who exalts himself shall be humbled, and he who humbles himself shall be exalted" (Lk. 18:14). It is also a vital principle for social reconstruction. As Dr. Orestes A. Brownson says in The Moral and Social Influence of Devotion to Mary, "the whole order of Christian civilization is founded on humility, and on respect for the humble and compassion for the poor and friendless, the needy and the helpless" (pp. 11).

Never was a greater treatise on humility written than the seventh chapter of the Rule of St. Benedict wherein Benedict prescribes twelve steps to grow in humility: "Now, therefore, after ascending all these steps of humility, the monk will quickly arrive at that perfect love of God which casts out fear. Through this love, all that he once performed with dread, he will now begin to observe without effort, as though naturally, from habit, no longer out of fear of hell, but out of love for Christ, good habit and delight in virtue. All this the Lord will, by the Holy Spirit, graciously manifest in his workman now cleansed of vices and sins" (RB 7:67-70).

Labor

Labor was the law of the monastery. In his Rule, Benedict emphasized both manual and mental labor. Labor was a strict obligation on the monks. To the Benedictine, work and prayer were the two hinges on which the gate of Heaven would swing open. The difficulty of work was understood to be the punishment that God imposed on sinful men, making it effective in the day of retribution. Without manual labor, monasticism could not have flourished.

Moderation

Moderation was the rule of the Benedictine monastery, in contrast to the austerities of the earlier eastern asceticism. Benedict was writing a Rule that the ordinary man could obey. The monastic life was to be a pattern of Christian society and a working model of family life. Under it the Abbot could permit austerities as befitted the individual inclination of a particular monk.

In the earlier days of asceticism, many monks so denied themselves that they ate only twice a week. They subjected the body to excessive punishment. They kept long fasts, wore filthy clothing, denied themselves sleep and outwardly to men practiced severe penances. In the moderation of St. Benedict the monk was to be well fed, both as respects the quantity and quality of food. His clothing was warm, clean and suitable. When on occasion he went out from the monastery into the world the clothing was clean, dignified and well fitted. Sufficient sleep was demanded under the Rule, from seven to eight hours a day.

There was, likewise, moderation in labor, whether manual or intellectual, and in prayer, whether public or private. The monk lived a truly human life, which was perfectly balanced between the major daily occupations of prayer (ora), manual labor (labora), and spiritual reading (lectio divina). In contrast to the ascetic, the Benedictine Rule dictated short personal prayer, yet most careful attention to the Divine Office (Officium Divinum).

Benedict was writing a Rule for the guidance of those who desired to renounce their own will and live an evangelical life where neither prayer nor study nor good works were over-emphasized.

Stability

The monk took a special vow of stability. He was to remain with his monastery for life, except in those cases, of course, where he was chosen to join a band to establish a new monastery. Stability was impressed upon him throughout the novitiate and he came to understand that his economic, social and religious security were rewards for his vow of stability.

Benedictine Life: A Means of Sanctification

Nothing in Benedictinism is an end unto itself, except the spiritual aim: "Let God be glorified in all things" (ut in omnibus glorificetur Deus). This was the spirit of the Rule and the motto of the Order.

Monasticism is not an end in itself, but a means of sanctification, the result of which was the reformation of society. It is the perfect historical example of the application of Our Lord's words, "seek first the kingdom of God and His justice, and all these things shall be given you besides" (Mt. 6:33). Benedict's only real concern was that his monks were "hastening to the heavenly homeland" (RB 73:8) and that they all were striving to "return to Him" (RB Prologue:2):

The reason we have written this rule is that, by observing it in monasteries, we can show that we have some degree of virtue and the beginnings of monastic life....Are you hastening towards your heavenly home? Then with Christ's help, keep this little rule that we have written for beginners. After that, you can set out for the loftier summits of the teachings and virtues we mentioned above, and under God's protection you will reach them. Amen. (RB 73:1, 8-9)

It cannot be over-emphasized that in considering the temporal benefits that flow from holiness, particularly communities of holy men and women striving to conform themselves to Christ the Lord, that we not lose sight of the real objective and the source of these secondary benefits, namely souls united to God by His grace, by His divine life dwelling in man through Charity.

Learning was not an objective. It was a bi-product of the striving to know God and later it was necessary because the monks had youth under their charge.

Good works were not an end unto themselves. They were simply a means of following Christ, who had once said to His disciples: "I was hungry, and you gave Me to eat; I was thirsty, and you gave Me to drink; I was a stranger, and you took Me in; naked, and you covered Me; sick and you visited Me; I was in prison, and you came to Me" (Mt. 25:35-36). Christ's revelation, that whenever these things were done to the least of His brethren they were done to Him, was the inspiration for the works of the monks.

Prayer was always an end unto itself. It was a partial fulfillment of man's destiny to sing the praises of the Creator.

Poverty was simply a means of renouncing the world and the ties that bind men to things temporal so that they might more easily "seek the things that are above, where Christ is seated at the right hand of God" (Col. 3:1).

Education, the founding of schools and the training of youth, were not Benedictine ends, but only bi-products of the care of oblates or donati within the monastic enclosure.

Obedience was not an end unto itself. It was simply a means of submitting the personal will to the will of God, as represented by the Abbot.

There was no art for art's sake in a Benedictine monastery. Painting, sculpture, architecture, the staining of glass and the writing of music, were all ordered to the Divine praise and served to remind men of God and His saints.

The collection of libraries and the copying of manuscripts were practical means for the wider use of the scriptures and ancient writings.

Thus in the phases of monastic life under the Rule, nothing was an end unto itself except the salvation of souls. Thus was fulfilled the words of St. Paul, "instaurare omnia in Christo" (cf. Eph. 1:10), to restore all things in Christ.

The Holy Rule

An examination of the 73 chapters of the Rule indicates that Benedict was not building a new monastic system, but merely laying down the rules which would cover the monasteries then in existence.

In his conception of the monastery as a Christian family, he writes nine chapters respecting the Abbot, or head of that family. The rules governing the Abbot are regulations which should govern the father of a family responsible for the souls of his children.

Benedict modified the Roman concept of the patria potestas or the absolute power of the father and joined it with the Christian conception of family life where the father represents Christ, is bound to obey the law of God, and most importantly, must give an account of the souls of his children on the day of judgment. The Abbot must seek the advice of the monks. In concerns of general interest to all, all were consulted. In concerns of special interest, those particularly gifted were consulted. The Abbot was under no responsibility to accept the advice given him, but seek that advice he must although he was bound to take full responsibility for his decisions. The buck stopped with the abbot, in spite of the consultative decision making process. Historians of profane history have wittingly or unwittingly overlooked the contribution of the Benedictine Rule to true democracy.

In this age of liberalism, we in America especially are apt to misunderstand the proper role of democracy. It will be good to recall simply that St. Thomas Aquinas taught that the best political system would fuse monarchy at the highest level, aristocracy at a subordinate level and democracy at the lowest level—at the level closest to the lives of people. Thus giving people real control over the events that effect them most. This is a type of application of the principle of subsidiarity. We see a great example of this in the monastic communities that follow the Rule of Benedict.

As 9 of the chapters of the Rule are devoted to the Abbot, 29 are devoted to the monks, 13 to the worship of God, 10 to internal administration and the remaining 12 to miscellaneous subjects. Benedict tells us that his Rule is a path intended for beginners. Close study indicates that its moderation, its reasonableness and its insight into the weaknesses of human nature and, above all, its common sense brought the supernatural life into exquisite harmony with the natural life.

God Loves to Build on Nothing

When Benedict wrote the Rule there was no Benedictine Order. There were monks galore in the East and in the West. There were rules that preceded the Rule of Benedict. St. Basil had written a rule; St. Augustine had a rule which was followed by the regular canons; Columbanus and the Irish monasteries had a rule.

Benedict not only thought of new monasteries but also of the right governance of those already in existence. He had lived the life of an ascetic and yet he was condemning individualism as he created his concept of the Christian monastic family.

The Rule was a minimum capable of being obeyed by all. Benedict did not set out to regenerate human society. He makes no promises as to results. He had no grandiose plans. He tells us frankly, he is writing a guide to sanctity for beginners. His whole life refutes the suggestion that he was conscious of any imprint he would leave on society.

He never put himself forward. He left no writings except the Rule. He never received the priesthood. Certainly he never planned a school system, never planned to preserve the classics of antiquity, never planned to dot Europe with cathedrals and monasteries, never planned the conversion of a continent, never dreamed of his influence on institutions and never planned the regeneration of the western world.

The divine reflection of success in his work is proof once again that God loves to build on nothing.

This work originally appeared in 1939 under the title of Back to Benedict. Its author, Louis B. Ward, is known to have written it shortly after having gone on a retreat at the Benedictine Abbey of St. Procopius in Lisle, Illinois (which still exists). It has been edited and abridged by The Angelus. A second and concluding part will appear in the September 2001 issue. It will discuss what the Rule of St. Benedict was and how and why, in practice, its application brought spiritual and temporal success for centuries.