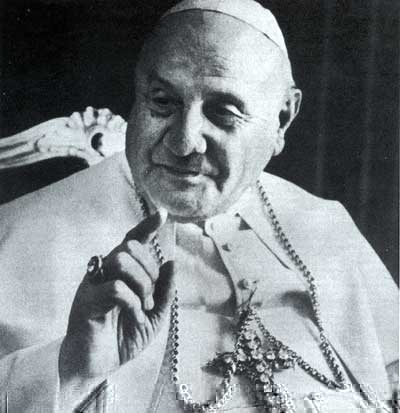

Was Good Pope Good Pope, Pt. 3

Part III

Rev. Fr. Michel Simoulin

This is the concluding segment of a three-part series challenging the "heroic virtue" ascribed to Pope John XXIII at his recent beatification (Sept. 3, 2000). The principles of Pope John XXIII which are being analyzed in this series are taken from the pope's own book, Journal of a Soul (published in 1964). Of this book, Pope John XXIII wrote, "My soul is in these pages."

We conclude this series by treating the fifth and sixth sophisms. The article originally appeared in the Society of Saint Pius X's Italian publication, La Tradizione Cattolica (Anno XI, n. 2 [43] 2000), and was translated by Angelus Press.

In the second installment of this series (The Angelus, Oct. 2000, pp. 28-31), we discussed the fourth sophism of Pope John XXIII, "It is opportune to employ mercy rather than severity and condemnations." We will attempt to show how in his encyclical Pacem in Terris (April 11, 1963), Pope John XXIII effectively further compromised the integrity of Catholic truth by promoting convergence with error over a wholesale return to Catholic doctrine.

5th Sophism: Aggravation of the 4th Sophism in Pacem in Terris

We start by quoting a pertinent passage from Pacem in Terris which must be read carefully in order to understand our critique to follow:

It is always perfectly justifiable to distinguish between error as such and the person who falls into error—even in the case of men who err regarding the truth or are led astray as a result of their inadequate knowledge, in matters either of religion or of the highest ethical standards. A man who has fallen into error does not cease to be a man. He never forfeits his personal dignity; and that is something that must always be taken into account. Besides, there exists in man's very nature an undying capacity to break through the barriers of error and seek the road to truth. God, in His great providence, is ever present with His aid. Today, maybe, man lacks faith and turns aside into error; tomorrow, perhaps, illumined by God's light, he may indeed embrace the truth....

Again, it is perfectly legitimate to make a clear distinction between a false philosophy of the nature, origin and purpose of men and the world, and economic, social, cultural, and political undertakings, even when such undertakings draw their origin and inspiration from that philosophy. True, the philosophic formula does not change once it has been set down in precise terms, but the undertakings clearly cannot avoid being influenced to a certain extent by the changing conditions in which they have to operate. Besides, who can deny the possible existence of good and commendable elements in these undertakings, elements which do indeed conform to the dictates of right reason, and are an expression of man's lawful aspirations?

It may sometimes happen, therefore, that meetings arranged for some practical end—though hitherto they were thought to be altogether useless—may in fact be fruitful at the present time, or at least offer prospects of success.

In this excerpt, we can identify three additional sub-sophisms falling under Pope John XXIII's primary sophism, "It is opportune to employ mercy rather than severity and condemnations." In order to live up to this primary sophism, the pope has established three more relevant sophisms arising from false distinctions in Pacem in Terris: 1) "It is always perfectly justifiable to distinguish between error as such and the person who falls into error"; 2) we should not make any connection between false philosophy and historic movements and, because of this, 3) it is possible for Catholics to adhere and collaborate with these historic movements.

1) "It is always perfectly justifiable to distinguish between error as such and the person who falls into error."

We must examine this first sub-sophism. St. Thomas Aquinas says, "Truth and falsehood exist in the intellect."1 Both are immanent acts of the intellect, and they do not exist outside of the intellect. Error is therefore an act of the intellect which remains in the one erring; it is part of the very person erring, and it [the error] is distinguished from him only by a distinction of reason. It is not a reality different from the mind of the one erring, whose act is to formulate affirmative or negative judgments in an erroneous way.2

Because it is a privation of rightness in judgment, error is an evil, that is, a non-being. But it is also the evil of the very one erring, that is, a privation of being and of those elements that are required for the correct formulation of judgment. Therefore, if it is true that error must not be confused with the one erring, it cannot be forgotten that error is the evil of the one erring, in whom the error causes a diminution of perfection and of dignity. The one erring cannot be considered independently from his error as if he were no different from one not erring. The person erring does not have the same dignity as one who adheres to the truth. The one erring professes error; his mind adheres to error.

2) Do not make any connections between false philosophy and historic movements.

It is apparent to us that this false distinction was made to accommodate communism. And it is with this judgment in mind that we speak.

It is common sense to say that communism is none other than the practice of Marxism. One does not go without the other, and one by itself loses all meaning. But let us examine the matter more profoundly with Prof. Romano Amerio who has written in Iota Unum:

John's thesis is derived from the Church's constant teaching that one ought to distinguish between error and the man; between the purely logical aspect of assent, and an assent as the act of a person. A contingent defect in one's convictions does not alter a person's destination to truth, or the axiological dignity that derives from it. That dignity comes from man's origin and his other worldly goal, that no event within this world can remove, and which in fact can never be lost: it is a dignity that remains even in the damned. But the encyclical moves from this distinction between a man and his errors, to a distinction between doctrines and the movements inspired by those doctrines, and it depicts the doctrines as unchangeable and closed within themselves, while the movements are caught in the flow of history and continually in fieri, always open to new events which will transform them even to the point of making them the reverse of what they were. But the legitimate distinction between the movement, that is, the mass of men agreeing together, and the idea inspiring the movement, cannot be so absolute as to make the doctrines fixed, while leaving the movements subject to change. Just as the initial movement that sprang from the doctrine cannot be conceived except as a mass of men agreeing on that doctrine, so it is impossible to imagine the doctrine remaining without any adherents, and the mass of men nevertheless staying together without any reference to that doctrine, simply drifting with historical events. The mass moves because it goes on thinking over its doctrines, and the doctrines share in historical change precisely because they are the ideas of men in motion. What, moreover, is the history of philosophy, if not the history of intellectual systems in their development and their becoming? How can one say that the systems are fixed and that only the men who think them move?

It would therefore seem that the encyclical obscures the continuing dialectical nexus between what the masses of a movement think (granting that they think it less clearly than the theoreticians) and what they do; and that the encyclical also implies that what they do has no present connection with an ideology, that, apparently, did nothing more than start the movement in the first place. The fact that thought precedes action is overlooked, so that ideologies seem to be begotten by movements, instead of begetting them. Ideologies do indeed feel the influence of changeable men, changing in the course of time, but the essential question remains the same, namely, whether the changing movements do or do not continue to draw their inspiration from the principles that gave them birth.3

3) It is possible for Catholics to adhere and collaborate with these historic movements.

To the contrary, Prof. Amerio writes:

Having neatly divided a movement from its ideology, in order to allow Catholics to join the movement while maintaining their reservation about the ideology, the encyclical proceeds to announce another criterion by which Catholics are permitted to co-operate with alien political forces. "Furthermore," it says, "who can deny that there are in those movements elements that are positive and worthy of approval, to the extent that such movements conform to the dictates of right reason and are the spokesmen of the just aspirations of the human person?" John's thesis is redolent of the Church's old and standard practice, formulated by St. Paul: Omnia autem probate, quod bonum est tenete [i.e., "Test all things, hold to what is good" (I Thess. 5:21)]. But in the Apostles' view of it, it is not a matter of experiencing, that is, taking a practical part in the movement, but of examining to discern and appropriate in practice whatever positive elements may be found in some movement.

It nonetheless remains true that the consent and co-operation that are legitimate when men turn their minds to lesser and contingent ends become illegitimate when they turn them to supreme and final ends that are mutually incompatible. In the Catholic view, the whole of political life is subordinate to an ultimate other-worldly end, while for communism it is directed exclusively at this world and should repudiate any transcendent end. Be it noted, communism not only prescinds from that end, as does liberalism, it positively repudiates it. So then, if communism is condemned, it is not the subordinate ends it presumes that are condemned, but its ultimate quest for an absolutely this-worldly organization of the world, to which its subordinate activities are directed: a quest incompatible with the ends pursued by religion. The reality is, that when two agents having contradictory ultimate goals participate in the same works, there is no co-operation, except in a material sense, because actions derive their character from the end that is being pursued and here the ends are contradictory. The outcome of the material co-operation will conform to the wishes of whichever party has been clever enough to get what it wants. [At this point in his original text, the author makes this footnote: "When Roncalli was Patriarch of Venice, he expounded the idea of co-operation between ultimately contradictory forces in a message to the congress of the Italian Socialist party in 1957, talking about 'common striving towards ideals of truth, goodness, justice, and peace.'" —Ed.]

The positive elements in the movement are considered in the encyclical as if they were distinctive of communist ideology, when in fact they are primarily religious values, since religion includes natural justice, and they only receive their full significance and force when they are put back into the setting of religious ideals. It is thus not enough just to recognize the values, one must recognize them as part of a larger truth and reclaim them for religion so as to restore them to their full integrity. Pacem in Terris does not attempt this process of reclamation, whereby what appears good and reasonable in a movement is plucked out of it, and restored to its religious setting. Instead, the encyclical expatiates on the recognition of values that are allegedly to be found on an equal footing in the movement and in Christianity; values that must therefore be derived from some prior source common to both, and which is thus what actually gives value to both. Just what this true, authentic source of values is, does not appear in the encyclical; nor could it, without the primary value of religion being sacrificed to that original underlying good [emphasis in original].4

On the contrary: There are many arguments from authority against the ideas of Pope John XXIII in Pacem in Terris. We will even quote John XXIII, who stands in contradiction to himself. Here are some notable sources:

Bl. Pope Pius IX: "To this goal also tends the unspeakable doctrine of Communism, as it is called, a doctrine most opposed to the very natural law. For if this doctrine were accepted, the complete destruction of everyone's laws, government, property, and even of human society itself would follow." (Qui Pluribus, 1864 [available from Angelus Press; price: $3.25].)

Pope Leo XIII: "You understand, Venerable Brethren, that We speak of that sect of men who, under various and almost barbarous names, are called socialists, communists, or nihilists, and who, spread over all the world, and bound together by the closest ties in a wicked confederacy, no longer seek the shelter of secret meetings, but, openly and boldly marching forth in the light of day, strive to bring to a head what they have long been planning—the overthrow of all civil society whatsoever." (Quod Apostolici Muneris, 1878.)

Pope Pius XI: "[A]nd when they have attained to power, it is unbelievable, indeed it seems portentous, how cruel and inhuman they show themselves to be. Evidence for this is the ghastly destruction and ruin with which they have laid waste immense tracts of Eastern Europe and Asia, while their antagonism and open hostility to Holy Church and to God Himself are, alas! but too well-known and proved by their deeds" (Quadragesimo Anno, 1931 [Available from Angelus Press; price: $1.25].)

Pope Pius XI: "Nevertheless, the struggle between good and evil remained in the world as a sad legacy of the original fall. Nor has the ancient tempter ever ceased to deceive mankind with false promises. It is on this account that one convulsion following upon another has marked the passage of the centuries, down to the revolution of our own days. This modern revolution, it may be said, has actually broken out or threatens everywhere, and it exceeds in amplitude and violence anything yet experienced in the preceding persecutions launched against the Church. Entire peoples find themselves in danger of falling back into a barbarism worse than that which oppressed the greater part of the world at the coming of the Redeemer. This all too imminent danger, Venerable Brethren, as you have already surmised, is bolshevistic and atheistic Communism, which aims at upsetting the social order and at undermining the very foundations of Christian civilization ....

"In the beginning Communism showed itself for what it was in all its perversity; but very soon it realized that it was thus alienating the people. It has therefore changed its tactics, and strives to entice the multitudes by trickery of various forms, hiding its real designs behind ideas that in themselves are good and attractive. Thus, aware of the universal desire for peace, the leaders of Communism pretend to be the most zealous promoters and propagandists in the movement for world amity. Yet at the same time they stir up a class warfare which causes rivers of blood to flow, and, realizing that their system offers no internal guarantee of peace, they have recourse to unlimited armaments. Under various names which do not suggest Communism, they establish organizations and periodicals with the sole purpose of carrying their ideas into quarters otherwise inaccessible. They try perfidiously to worm their way even into professedly Catholic and religious organizations. Again, without receding an inch from their subversive principles, they invite Catholics to collaborate with them in the realm of so-called humanitarianism and charity; and at times even make proposals that are in perfect harmony with the Christian spirit and the doctrine of the Church. Elsewhere they carry their hypocrisy so far as to encourage the belief that Communism, in countries where faith and culture are more strongly entrenched, will assume another and much milder form. It will not interfere with the practice of religion. It will respect liberty of conscience. There are some even who refer to certain changes recently introduced into Soviet legislation as a proof that Communism is about to abandon its program of war against God.

"See to it, Venerable Brethren, that the Faithful do not allow themselves to be deceived! Communism is intrinsically wrong, and no one who would save Christian civilization may collaborate with it in any undertaking whatsoever..." (Divini Redemptoris, 1937 [Available from Angelus Press; price: $4.25].)

Pope Pius XII: Decree of the Holy Office Against Communism, June 28 (July 1) 1949; Ed.: AAS 41(1949) 334:

Questions: 1) Is it allowed to be a member of the Communist party or to lend it support? 2) Is it allowed to publish, distribute or read books, magazines, journals or leaflets that defend the doctrine and action of communists or contribute to them? 3) Can those faithful Christians who have consciously and freely discharged the actions mentioned in Numbers 1) and 2) be admitted to the sacraments? 4) Do the faithful Christians who profess the materialistic and anti-Christian doctrine of the communists, and especially those who distribute and propagate it, by that very fact, incur, as apostates from the Catholic Faith, excommunication reserved in a special way to the Apostolic See?

Reply (confirmed by Pope Pius XII on 20 June):

To 1) No. Communism in fact is materialistic and anti-Christian; Communist leaders, even if now and then in word they agree not to fight against religion, nevertheless in reality, both in doctrine and in action, they show themselves to be opposed to God, to the true religion and to the Church of Christ.

To 2) No. They are prohibited in fact by the law itself (1917 Code of Canon Law, Canon 1399).

To 3) No, according to principles of a general nature that regard the exclusion from the sacraments of those who are not disposed.

To 4) Yes.

Most remarkable testimonies come from Angelo Roncalli himself while Patriarch of Venice and as Pope John XXIII:

...I must draw attention with distinct regret of my spirit to the ascertainment of the pertinacity observed in some of maintaining at any cost the so-called opening to the left, contrary to the clear position taken by the most authoritative hierarchies of the Church....[W]e are in the face of a most grave doctrinal error and of a flagrant violation of Catholic discipline. The error is that of, in practice, taking sides and of consorting with an ideology—the Marxist—which is the denial of Christianity....(Neither let it come to be said that this going to the left has the mere implication of prompter and broader reforms of an economic nature, since even in this sense the equivocation remains, and that is: the danger that the specious axiom that in order to have social justice it is absolute necessary to be associated with the deniers of God and the oppressors of human liberty may penetrate into men's minds. (Aug. 12, 1956)5

Pope John XXIII: Reply of the Holy Office Regarding Election of Congressmen Who Uphold Communism, March 25 (April 4) 1959; Ed.: AAS 51(1959) 271s:

Question: Is it allowed for Catholic citizens, in the election of representatives of the people, to vote for those parties or candidates that, even if they do not profess principles contrary to Catholic doctrine, and indeed claim the Christian name, nevertheless in fact are associated with communists and support the same by their way of acting?

Reply (confirmed by Pope John XXIII on April 2): No, according to the norm of the decree of the Holy Office of July 1, 1949, No. 1.

In its May 18, 1960 edition, the official newspaper of the Roman Curia, L'Osservatore Romano, weighed in with some "firm points" on the matter of which we extract Numbers 3 and 4 only:

3) In the political arena the problem of a collaboration with those who do not accept religious principles can present itself: it is due then to the Ecclesiastical Authority and not to the will of individual faithful to judge about the moral lawfulness of such collaboration, and a conflict between that judgment and the opinion of the faithful themselves is inconceivable in a truly Christian conscience: in any case it must be resolved by obedience to the Church, the custodian of the truth.

4) The irreversible antithesis between the Marxist system and Christian doctrine is per se ipsa evident, as that which opposes materialism to spiritualism, atheism to religious faith. Therefore the Church cannot permit the faithful to adhere, support or collaborate with those movements that adopt or follow the Marxist ideology and its applications. Such adherence or collaboration would inevitably lead to compromising and sacrificing the principles of Christian faith and morals.

Pope John XXIII: "Finally, both workers and employers should regulate their mutual relations in accordance with the principle of human solidarity and Christian brotherhood. Unrestricted competition in the liberal sense, and the Marxist creed of class warfare, are clearly contrary to Christian teaching and the nature of man ....

"Pope Pius XI further emphasized the fundamental opposition between Communism and Christianity, and made it clear that no Catholic could subscribe even to moderate Socialism. The reason is that Socialism is founded on a doctrine of human society which is bounded by time and takes no account of any objective other than that of material well-being. Since, therefore, it proposes a form of social organization which aims solely at production, it places too severe a restraint on human liberty, at the same time flouting the true notion of social authority" (Mater et Magistra, May 5, 1961).

Pope Paul VI: "These are the reasons which compel us, as they compelled our predecessors and, with them, everyone who has religious values at heart, to condemn the ideological systems that deny God and oppress the Church, systems which are often identified with economic, social and political regimes, amongst which atheistic communism is the chief" (Ecclesiam Suam, 1964).

However, we must take note of the commentary of Andrea Riccardi, author of Il Vaticano e Mosca [The Vatican and Moscow] on this condemnation of Paul VI:

Pope Paul VI in his first encyclical, Ecclesiam Suam, had not eluded the theme of communism. He had set himself on the same course as his "predecessors" in confirming the condemnation of all systems "recusant of God and oppressive of the Church" and among these especially atheistic communism....Paul VI was not, however, closed to discussions and encounter....Indeed, he had keenly added to the condemnation [of atheistic ideologies in Ecclesiam Suam] this remark: "It could be said that their condemnation comes not so much on our part, as a radical opposition of ideas and oppression of facts comes to us on the part of the systems themselves and regimes which personify those things. Our disapproval is, in reality, the lament of victims more than the sentence of a judge."

The text [of Pope Paul VI] presents the Church as a "victim" more than as a judge....Ecclesiam Suam, with great shrewdness, succeeded in maintaining equilibrium between the traditional continuity of Pontifical teaching on communism and Pope John XXIII's aggiornamento....In the document there was more or less an invitation, even though very general: "...[W]e do not despair that they [i.e., socialists—Ed.] may one day be able to enter into a more positive dialogue with the Church than the present one which we now of necessity deplore and lament." For the first time the politics of dialogue with non-believers and socialist regimes entered into an encyclical. We are a long ways from the censure of Pius XII against discussions and meetings of less than ten years ago.6

Pacem in Terris, called by some the "Anti-Syllabus," exceeds the diplomatic and ecumenical silence of Gaudet Mater Ecclesia [Pope John XXIII's opening address to the Council Fathers—Ed.] or even of Vatican II itself. While other documents are at the level of effecting a practical attitude, Pacem in Terris is a doctrinal betrayal. Heretics and communists recognized and publicly admitted the fact.

6th Sophism: Unity and Peace in Love

This sixth sophism is another spin-off on Pope John XXIII's fourth sophism already discussed, "It is opportune to employ mercy rather than severity and condemnation." We can see this basic line of thought emerge in his Inaugural Allocution of the Council (Oct. 11, 1962):

The Church's solicitude to promote and defend truth derives from the fact that, according to the plan of God, who wills all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth (I Tim. 2:4), men without the assistance of the whole of revealed doctrine cannot reach a complete and firm unity of minds, with which are associated true peace and eternal salvation.

Unfortunately, the entire Christian family has not yet fully attained this visible unity in truth.

The Catholic Church, therefore, considers it her duty to work actively so that there may be fulfilled the great mystery of that unity, which Jesus Christ invoked with fervent prayer from His heavenly Father on the eve of His sacrifice. She rejoices in peace, knowing well that she is intimately associated with that prayer, and then exults greatly at seeing that invocation extend its efficacy with salutary fruit, even among those who are outside her fold.

Indeed, if one considers well this same unity which Christ implored for His Church, it seems to shine, as it were, with a triple ray of beneficent supernal light: namely, the unity of Catholics among themselves, which must always be kept exemplary and most firm; the unity of prayers and ardent desires with which those Christians separated from this Apostolic See aspire to be united with us; and the unity in esteem and respect for the Catholic Church which animates those who follow non-Christian religions.

In this regard, it is a source of considerable sorrow to see that the greater part of the human race—although all men who are born were redeemed by the blood of Christ—does not yet participate in those sources of divine grace which exist in the Catholic Church. Hence the Church, whose light illumines all, whose strength of supernatural unity redounds to the advantage of all humanity, is rightly described in these beautiful words of St. Cyprian: "The Church, surrounded by divine light, spreads her rays over the entire earth. This light, however, is one and unique and shines everywhere without causing any separation in the unity of the body. She extends her branches over the whole world. By her fruitfulness she sends ever farther afield her rivulets. Nevertheless, the head is always one, the origin one, for she is the one mother, abundantly fruitful. We are born of her, are nourished by her milk, we live of her spirit" (De Catholicae Eccles. Unitate, 5).

This unity and peace would be the object of the aggiornamento promised by the Second Vatican Council. But, as we have already noted in our response to Pope John XXIII's fourth sophism, it is a unity that prescinds from the faith. Note what Angelo Roncalli, the future pope, wrote in 1927: "How the times have changed! But the charity of Catholics is demanded to make the hour of the return of our brothers to the unity of the fold hasten. Understand? Charity, much more than scientific discussions."7

In the opening speech of the Council, Pope Roncalli speaks of the "aid of the whole of revealed doctrine," but this is not the same thing as the necessity of faith. Furthermore he speaks of "salutary fruits" of the prayer of Christ for unity among those who are outside the "bosom" of the Church because "this very unity implored by Christ for his Church seems almost to shine with a triple ray of heavenly, beneficent light." The author, Carlo Falconi, comments:

The meeting between the Catholic Church and the world on concrete ground concerning the problems and needs of the world must not be other than a means for establishing dialogue in order to secure the fundamental "unity of the human family" which, according to the Pope, is "the great mystery that Jesus Christ invoked with ardent prayer from His heavenly Father at the approach of his sacrifice." And for the first time John XXIII alludes to the "triple ray of heavenly, beneficent light" of unity, or of ecumenism, which should radiate from the Council, that is, unity of Catholics, unity with separated Christians, and unity with non-Christian peoples [emphasis added].8

In the book Il Vaticano II, from which we have already quoted in our commentary on Pope John XXIII's third sophism, author Giuseppe Dossetti summarizes Paragraphs 13-16 of the Vatican II document Lumen Gentium, which aligns with Pope John XXIII's "triple ray" of unity:

The single people of God has a potentially universal extension, according to diverse orders: firstly the Catholics, who are "fully" incorporated; then the baptized who do not profess the integral Faith or who do not retain the unity of communion with the successor of Peter, but who are nevertheless still attached by the common possession of the Sacred Scriptures, and by the other sacraments, the Eucharist included; then the non-Christians (Jews, Muslims, and others) who sincerely look for God and, under the influence of grace, strive to fulfill the will of God, known through the dictates of conscience, are able to attain eternal salvation.

The position of Pope John XXIII should not surprise us. The year after having been consecrated bishop (March 19, 1925) and made Apostolic Visitor in Bulgaria, he wrote this letter to an Orthodox youth wishing to be ordained in that schismatic sect. (Bulgaria is an Eastern European country bordered by Romania to the north, Turkey to the south, the Black Sea on the east, and Yugoslavia and Macedonia on the west. Its capital is Sofia which, with a population of nearly 9 million, is its largest city.—Ed.)

|

On the contrary: The message delivered by Roncalli in the letter just quoted is seriously challenged for its ecumenical intent by his papal predecessors.

In his Syllabus of Errors, Bl. Pope Pius IX condemns as false the following theses:

15) Every man is free to embrace and profess that religion which, guided by the light of reason, he shall consider true. (Allocution Maxima Quidem, June 9, 1862; Damnatio Multiplices Inter, June 10, 1851.)

16) Man may, in the observance of any religion whatever, find the way of eternal salvation, and arrive at eternal salvation. (Encyclical Qui Pluribus, Nov. 9, 1846.)

17) Good hope at least is to be entertained of the eternal salvation of all those who are not at all in the true Church of Christ. (Encyclical Quanto Conficiamur, Aug. 10, 1863, etc.)

18) Protestantism is nothing more than another form of the same true Christian religion, in which form it is given to please God equally as in the Catholic Church. (Encyclical Noscitis, Dec. 8, 1849.)

38) The Roman pontiffs have, by their too arbitrary conduct, contributed to the division of the Church into Eastern and Western. (Apostolic Letter Ad Apostolicae, Aug. 22, 1851.)

A most extraordinary condemnation of Pope John XXIII's sophistry comes from the encyclical Mortalium Animos of Pope Pius XI [available from Angelus Press]:

Never perhaps in the past have we seen, as we see in these our own times, the minds of men so occupied by the desire both of strengthening and of extending to the common welfare of human society that fraternal relationship which binds and unites us together, and which is a consequence of our common origin and nature....

A similar object is aimed at by some, in those matters which concern the New Law promulgated by Christ our Lord. For since they hold it for certain that men destitute of all religious sense are very rarely to be found, they seem to have founded on that belief a hope that the nations, although they differ among themselves in certain religious matters, will without much difficulty come to agree as brethren in professing certain doctrines, which form as it were a common basis of the spiritual life....

And here it seems opportune to expound and to refute a certain false opinion, on which this whole question, as well as that complex movement by which non-Catholics seek to bring about the union of the Christian churches depends. For authors who favor this view are accustomed, times almost without number, to bring forward these words of Christ: 'That they all may be one....And there shall be one fold and one shepherd' (Jn. 17:21, 10, 16); with this signification, however: that Christ Jesus merely expressed a desire and prayer, which still lacks its fulfillment. For they are of the opinion that the unity of faith and government, which is a note of the one true Church of Christ, has hardly up to the present time existed, and does not exist today. They consider that this unity may indeed be desired and that it may even be one day attained through the instrumentality of wills directed to a common end, but that meanwhile it can only be regarded as a mere ideal. They add that the Church in itself, or of its nature, is divided into sections; that is to say, that it is made up of several churches or distinct communities, which still remain separate, and although having certain articles of doctrine in common, nevertheless disagree concerning the remainder; that these all enjoy the same rights; and that the Church was one and unique from, at the most, the apostolic age until the first Ecumenical Councils. Controversies therefore, they say, and long-standing differences of opinion which keep asunder till the present day the members of the Christian family, must be entirely put aside, and from the remaining doctrines a common form of faith drawn up and proposed for belief, and in the profession of which all may not only know but feel that they are brothers. The manifold churches or communities, if united in some kind of universal federation, would then be in a position to oppose strongly and with success the progress of irreligion ....

These pan-Christians who turn their minds to uniting the churches seem, indeed, to pursue the noblest of ideas in promoting charity among all Christians; nevertheless how does it happen that this charity tends to injure faith? Everyone knows that John himself, the Apostle of love, who seems to reveal in his Gospel the secrets of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and who never ceased to impress on the memories of his followers the new commandment, "Love one another," altogether forbade any intercourse with those who professed a mutilated and corrupt version of Christ's teaching: "If any man come to you and bring not this doctrine, receive him not into the house nor say to him: God speed you" (II Jn. 10). For which reason, since charity is based on a complete and sincere faith, the disciples of Christ must be united principally by the bond of one faith. Who then can conceive a Christian Federation, the members of which retain each his own opinions and private judgment, even in matters which concern the object of faith, even though they be repugnant to the opinions of the rest?...

Let, therefore, the separated children draw nigh to the Apostolic See, set up in the City which Peter and Paul, the Princes of the Apostles, consecrated by their blood; to that See, We repeat, which is "the root and womb whence the Church of God springs" (St. Cyprian, Ep. 48 ad Cornelium, 3), not with the intention and the hope that "the Church of the living God, the pillar and ground of the truth" (I Tim. 3:15) will cast aside the integrity of the faith and tolerate their errors, but, on the contrary, that they themselves submit to its teaching and government. (Mortalium Animos, Jan. 6, 1928)

Under Pope Pius XII, the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office wrote a letter to Richard Cardinal Cushing, Archbishop of Boston, Massachusetts [published in its entirety in Baptism of Desire: A Patristic Commentary (Angelus Press)]:

Therefore, no one will be saved who, knowing the Church to have been divinely established by Christ, nevertheless refuses to submit to the Church or withholds obedience from the Roman Pontiff, the Vicar of Christ on earth....But it must not be thought that any kind of desire of entering the Church suffices that one may be saved. It is necessary that the desire by which one is related to the Church be animated by perfect charity. Nor can an implicit desire produce its effect, unless a person has supernatural faith... (Protocol No. 122/49, Aug. 8, 1949).

Pope Pius XII declared unequivocally in Ecclesia Catholica (Dec. 20, 1949), "The Catholic Church possesses the fullness of Christ."

Response to the Sixth Sophism

What price "peace and unity in love?" St. Thomas Aquinas frames the argument by establishing some definitions:

There can be concord in evil between wicked men. But "there is no peace to the wicked" (Is. 48:22). Therefore peace is not the same as concord. (ST, II-II, Q29, Art. l)

There can be no true peace except where the appetite is directed to what is truly good, since every evil, though it may appear good in a way, so as to calm the appetite in some respect, has nevertheless many defects, which cause the appetite to remain restless and disturbed. Hence true peace is only in good men and about good things. The peace of the wicked is not a true peace but a semblance thereof, wherefore it is written (Wis. 14:22): "Whereas they lived in a great war of ignorance, they call so many and so great evils peace." (ST, II-II, Q. 29, Art. 2 ad 3)

Without sin no one falls from sanctifying grace, for it turns man away from his due end by making him place his end in something undue: so that his appetite does not cleave chiefly to the true final good, but to some apparent good. Hence without sanctifying grace, peace is not real, but merely apparent. (ST, II-II, Q. 29, Art. 3 ad 1).

We can see that if true faith, grace, or charity are disregarded, there is the possibility of establishing something akin to "concord" among men of "goodwill." And, if all men were of such goodwill, "universal concord" could be established.

This is the dream of the humanists, the spiritualists, the pacifists, and the philanthropists who are "not hostile in principle toward Christ" and who concede to Him "the importance and the dignity of Messias."10

However, "[this] is not a matter of a true peace, but of a surrender in the presence of errors, of falsehoods, of the false principles of the world: and true peace cannot reside in that. True peace is a defense of the Truth, a triumph of Truth. It is the tranquillity of order, not of that general disorder in which every conflict becomes impossible, since the very notions of good and evil, of true and false, are no longer distinguishable."11

In reality, for the humanitarians, for the pacifists, the philanthropists, philanthropy has taken the place of charity, contentment has replaced hope, and faith has been deposed by culture.12 True peace is not the fruit of natural forces alone. The intervention of divine grace is required, since peace, with charity and joy, is the fruit of the Holy Ghost, who does not act unless there is faith in Christ.

The price for false peace and love is ecumenism, concludes Romano Amerio:

Traditional teaching on Christian unity is set forth in the Instructio de Motione Oecumenica [i.e., Instruction on the Ecumenical Movement, AAS, Jan. 31, 1950—Ed.] published by the Holy Office on December 20, 1949, which takes up the teaching of Pius XI in his encyclical Mortalium Animos of 1928. The principles laid down are: First: "the Catholic Church possesses the fullness of Christ," that is, it does not need to acquire things that go to make up the fullness of Christianity from other denominations. Second: Christian unity must not be pursued by means of a process of assimilation between different confessions of faith, or by adjusting Catholic doctrine to the teachings of other denominations. Third: true union between the churches can come about only by the return, per reditum, of separated brethren to the true Church of God. Fourth: separated brethren who rejoin the Catholic Church lose nothing of the truth to be found in their own denominations, rather they retain it just as it was, but in its completed and perfected context, complementum atque absolutum.

The doctrine set forth in the Instructio therefore implies that the Church of Rome is the foundation and center of Christian unity, that the Church's life in time does not revolve around a number of centers, namely the different Christian groupings, all of which have a single deeper center situated beyond all of them, but rather that the Catholic Church is itself the collective person or body of Christ; and lastly that the separated brethren must move towards the unmoving center which is the Church served by the successor of St. Peter. The rationale or center of Christian unity is therefore something that already exists within human history and which the separated brethren need to regain; it is not something to be constructed in the future. All the reserve that the Roman Church has exercised in ecumenical matters, and particularly its continuing abstention from the World Council of Churches, is motivated by this understanding of what Christian unity involves, and is designed to exclude the idea that all denominations stand on an equal footing. This doctrinal position is merely the expression of the transcendent principle upon which Christianity rests, namely Christ Himself, who is both God and man, and who is represented within time by the Petrine office.

The change introduced at the Council is apparent in outward signs and in a shift in theory. In the Conciliar decree Unitatis Redintegratio, the Instruction of 1949 is never mentioned, and the word return, reditus, never occurs. It is replaced by the idea of convergence. That is, the different Christian denominations, including Catholicism, should turn not to each other but towards the total Christ who is outside all of them, and upon whom they must converge.

It is true that in his speech opening the second period of the council, in 1963, Paul VI reiterated the traditional teaching that the separated brethren "lack that perfect unity that only the Catholic Church can give them." He went on to say that the threefold bond of this unity was constituted by a single belief, a sharing in the same sacraments and "due adherence to a unified ecclesiastical government," which latter included a great range of languages, rites, historical traditions, local prerogatives and currents of spirituality.

Despite this papal utterance, the Council's eventual decree on ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio, rejects the idea of a return of separated brethren and adopts the idea of a simultaneous conversion on the part of all Christians. Unity should be brought about not by a return of the separated brethren to the Catholic Church, but by a conversion of all the churches within the total Christ, a Christ who is not identified with any of them, but who will be constructed by means of their coming together as one. The preparatory schemas drawn up before the Council stated that the Church of Christ is the Catholic Church; but the Council says only that the Church of Christ subsists in the Catholic Church, in effect adopting the idea that it also subsists in other Christian churches, and that all such churches ought to recognize their common subsistence in Christ. As a professor at the Gregorian University put it, the Council recognizes that the separated churches are "instruments that the Holy Spirit uses to bring about the salvation of their members." On this egalitarian view of all Christian denominations, Catholicism is no longer seen as having any uniquely privileged position.

In his book Introdluction à l'oecumenisme, published in Paris in 1959 during the period in which the Council was being prepared, Fr. M. Villain had already attempted to do away with the contrast between the Catholic Church and Protestant denominations by distinguishing between central and marginal doctrines, and still more by distinguishing between the truths of the faith and the formulas by which they are expressed, which latter he said were not unchangeable. He maintained that doctrinal formulas do not manifest the truth, but rather categorize a datum that remains unknowable, and that Christian unity could be based on something more profound than truth, which he calls "the praying Christ." Prayer by all Christians is certainly needed to achieve unity, but it is not itself unity; Pope Paul said unity in faith, sacraments and government is what is required [emphasis in original].13

Unity is the privilege of God and Christ. The unity of the Church has its source only in Christ, whose Mystical Body it is. It enjoys the unity of Christ himself; it can neither lose it nor increase it, but only communicate the advantage of it to those who believe in Christ. Outside of this unity in the faith there is only union or concord, but no peace, even among "men of goodwill," which is not the same thing as men in the state of grace.

Conclusion

All this leads up to our getting something very straight. The pontificate of Pope John XXIII was the beginning of a monstrous unhinging from Catholic basics. The lay philosopher Ernest Hello writes:

We are told that evil has always existed on earth and this is true, after the fall. But the chief difference between the ordinary sicknesses of man and his actual death agony consists in this. At one time good was called good and evil was called evil. This distinction was an advantage for natural intelligence, supported and enriched, safeguarded and augmented by a remembrance of Pentecost. Today, on the moral map of the world, the borders are shifting. The domain of good and the domain of evil are not clearly defined; confusion has wiped out the sacred boundaries which protected conscience from perversity of judgment. Neither reason nor madness any longer succeed in knowing what their respective domains are. The father no longer speaks the same language as his son; the husband no longer speaks the same language as his wife. Brothers speak and do not understand each other. The metric system, which rules the world of bodies, is clearly not applicable in the world of souls. Equally, by comparison, the rejection of doctrinal unity leaves souls without any common measure. Discussion is necessarily sterile, because a common language does not exist. Quantities that do not have a common measure are incommensurable among themselves. By dint of confusion, we have become incommensurable among ourselves, on earth. (Ernest Hello, Il Secolo, 1896)

In fact, instead of removing the darkness from our hearts, the Second Vatican Council has judged it a better strategy to meet the darkness by yanking away from us some of the truths which the Church has enjoyed since its foundation. The fruits stare us in the face. After Pope John XXIII's Council, the world and the Church live in an amplified confusion: souls are messed up, families dispersed, societies consigned to the triple tyranny of pleasure, money, and the so-called "rights of man."

Pope Paul VI himself lamented the situation within the Church. On June 29, 1972, on the ninth anniversary of his coronation, he delivered a homily summarized by L'Osseraatore Romano (July 13, 1972):

Referring to the situation of the Church today, the Holy Father then affirmed that he had the feeling that "Satan's smoke has made its way into the temple of God through some crack." There is doubt, uncertainty, problems, restlessness, dissatisfaction, confrontation. People no longer trust the Church: they trust the secular profane prophet that speaks to us from some newspaper or from some social movement, running after him and asking if he has the formula of real life. And we do not realize that we are already owners and masters of it. Doubt has entered our consciences, and it has come in through windows that ought to be open to light.

Five years later (Sept. 8, 1977), the Holy Father was more outspoken:

There is a great disturbance, and what is in doubt is the faith. What strikes me when I consider the Catholic world is that all through Catholicism a non-Catholic kind of thinking seems at times to predominate—and it can happen that this non-Catholic thinking around Catholicism may become stronger tomorrow. But it will never represent the mind of the Church. At this moment what is lacking in Catholicism is coherence.14

But it was, indeed, Pope John XXIII who made incoherence the keynote of his pontificate, and he stamped it so profoundly that incoherence and confusion have since prospered. Still, it is not possible even today to express a few reservations on his government, his person, on his "goodness"!

The "voice of the people" called John XXIII the "good Pope." Surely it was not intended to mean other Popes had been evil, but that his particular smile and his simple speech attracted hearts. But the sentiments of the people are not always the voice of God, especially when they are nourished by the propaganda of the mass media. On the contrary, we should be suspicious of the human praise of the world for the vicar of Him whom the world has hated. The Orthodox, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, liberals, masons, modernists, socialists, and communists all exalted the "goodness" of Pope John. We know, on the other hand, how Pius IX was hated by the world, by the ideological revolutionaries, the masons, the liberals or socialists. "To the river!" was the cry of the revolutionary world while the corpse of Bl. Pope Pius IX was being carried to San Lorenzo three years after his death!

The devotion of Pope John XXIII for Pius IX has been talked about. In the audience held at Castelgandolfo (Aug. 22, 1962), John XXIII pointed out the different popes who promoted devotion to the Immaculate Heart of Mary:

The other pontiff is the Servant of God, Pius IX; the Pope of the Immaculata; sublime and admirable figure of a pastor, of whom it was also written, in bringing it together with the image of our Lord Jesus Christ, that no one was loved and hated by his contemporaries more than he. But his activities for and his dedication to the Church shine today more brightly than ever; the admiration for him is unanimous; and His Holiness loves to confide to his listeners a fond hope that he cherishes in his heart: that he may grant to him, that is our Lord, the great gift of being able to confer the honors of the altar to him who summoned and celebrated the 20th Ecumenical Council, Vatican I, during the course of the 21st Ecumenical Council.15

All well and good. Without wishing to cast the sincerity of this devotion into doubt, we ask whether John XXIII, besides devotion to Pius IX, Pope of the Immaculata and of Vatican I, was devoted to Pius IX, Pope of the Syllabus of Errors. It can easily be surmised that his aggiornamento would have been condemned by Pope Pius IX: the "opening" to the "fresh" air of the time, namely the "opening" to liberalism and to modernism, with the promotion of liberal and modernist theologians and prelates; the "opening" to non-Catholics, heretics, and schismatics and even non-Christians; the "opening" to the masons; the "opening" to the left, to communism, to all enemies of the Church, all presumed "men of goodwill."

This anecdote, reported in the journal Le Monde (Nov. 13, 1962) is well-known:

Theologians like to express themselves in this business that closely concerns doctrine. Until the Council, John XXIII had proven to be rather evasive. "Are you a theologian?" he recently asked a Catholic guest of importance. "No." "Well, Deo Gratias! Neither am I, although it is necessary to maintain it. You yourself see how many misfortunes theologians by profession have inflicted on the Church on account of their sophistry, their self-love, their narrow-mindedness and their obstinacy."16

Perhaps Pope John XXIII did not doubt the Church and the necessity of faith, but he seems to have doubted that the Church was the unique font of peace for men, with its doctrine, its sacraments, and the grace of the Holy Ghost given to those who have faith in Christ. The Church becomes therefore, for him, only an "aid" for establishing peace, a "partner" in the work of the restoration of unity and peace on earth among all men. Having always given priority to the love of the one erring over the love of the truth and the condemnation of error, the sophisms of John XXIII enfeebled the Church and touched off within her the ruin of theology and teaching, the apostolic zeal of the clergy, and the faith of the Catholic people.

From Condemnation to Concord

In the very beginning of our series we pointed out the violence of the reproaches of Pope John XXIII aimed at the "prophets of doom," those men he thought too faithful to the popes of the past as well as recent ones, who have not known how to read the "signs of the times." So, if on one hand his opening allocution of the Second Vatican Council, Gaudet Mater Ecclesia, engenders in kernel the principal doctrines that are expanded and proposed in the more significant conciliar documents (Gaudium et Spes, Lumen Gentium, etc.), on the other it does not totally know how to hide a rather contemptuous judgment on the Church "of the past," judged too closed to non-Catholics and not very merciful.

A similar evolution can be noted in Roncalli in distancing himself from the traditional attitude of the Church. This is true of Freemasonry,17 but also of communism and other enemies of the Church. This evolution goes from refusal to tolerance, in order to arrive at an implicit concord. The liberal, Fr. Marie-Dominique Chenu, saw it happen: "The long refusal...then, one day, the change, with John XXIII. He had to authorize what had been explicitly condemned."18

Three Very Serious Injuries

Having repudiated the Catholic attitude of his predecessors and of the Roman Curia, Pope John XXIII caused three very serious injuries to the Church and to humanity: 1) He disarmed the Church, opening it to all its adversaries hitherto condemned and held at bay by, among other Popes, Bl. Pius IX, Pope St. Pius X, and Pope Pius XII. Indeed, he allowed the venomous modernist current to assume direction of the Council and of the Church. 2) He extinguished the energy and the apostolic zeal of Catholics and of the hierarchy both in the defense of the rights of our Lord Jesus Christ and the Church as well as in the spreading of the faith and of holy charity. 3) He gave a certificate of integrity to leftist ideologies and left the entire world, besides the Church itself, at the mercy of evils most dangerous to peace, that is for the tranquillity of order: socialism, communism, masonry, liberalism, revolution, false religions, sects, etc.

Thanks to Pope John XXIII, for example, after the opening to the left in Italy and elsewhere and after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, all Europe is dominated politically and intellectually by the leftist ideology. The ideology of universal brotherhood, which found in him a friend and an authoritative preacher, has served only the masonic ideologies or men joined in league in order to take from Christ all power or authority over human society.

We ask whether he can be judged a "good pastor," a "good Pope," and be beatified, that is, glorified and emulated by the faithful, though he handed the sheep over—even those who are still not in the fold of Christ—to the communist and masonic wolves. Though they have changed masks and methods, they are nevertheless what they have always been, exposed and condemned by all good pastors and even more dangerous today because their ways are concealed under the expressions of "peace, philanthropy, humanitarianism, and freedom of conscience." "The true enemy of Christianity is not he who is obviously against it, but he who adulterates it from inside....[W]hen communism entangles religion, and speaks in its name, then it shows its ultimate harmfulness."19

Double Trouble

The beatification of Pius IX and John XXIII places us before an insoluble dilemma because two opposite models of sanctity have been proposed to us: the "classic sanctity" of the Church, that which is born from openness to the holiness of God by means of Jesus Christ, of the Gospel and of Holy Church, and that of the "new sanctity," which is born from "dialogue" and from "openness" to the "goodness" of men by means of a Gospel reinterpreted in light of modern thought, adapted to the "new order" of things and which teaches faith in the "goodwill" of all men without distinctions. Do we follow and imitate the Pope of the condemnation of communism, or the Pope of the silence on communism? The religious Pope or the "political" Pope?

In beatifying John XXIII, the conciliar Church beatifies its Council and all its work of "auto-destruction." We ask Bl. Pius IX, the Pope of the Immaculata, of Vatican I, of the Syllabus of Errors, and of the first condemnation of communism, to cover with his holy shadow Bl. John XXIII, the Pope of the refusal to reveal the Secret of Our Lady of Fatima, the Pope of Vatican II, of the Anti-Syllabus, and of silence on communism.

Fr. Berto, Archbishop Lefebvre's personal theologian while at the Second Vatican Council, now deceased, said: "The Trinity, the Incarnation, the Redemption, the Eucharist, Grace, are and will always be perfectly unchangeable truths; now they are the very soul of Catholicism; then why do they speak to us of adapting Catholicism to the men of our time, who, besides, are no different from the men of all times?"

And, finally, we conclude with the words of Ernest Hello, a stinging rebuke to this pope who was not good where he needed to be so:

He who loves truth detests error. It is a truth, so simple that it appears to be a paradox. But this detestation of error is the touchstone with which the love for truth is recognized. If you do not love truth, you are able as well, until a certain point, to affirm loving it or to stop believing it; however you are certain that you do not have a horror for falsehood, and this will be the sign by which others will know that you do not love truth.

He who once loved the truth and later on no longer loves it, does not immediately declare his defection, but begins by detesting the error less than before. And thus he deceives himself.

The secret acquiescences of man constitute one of the most unknown aspects of the history of the world.

When one no longer has a love for the doctrine, whether good or evil, which he once professed, usually he retains the symbol of that doctrine; however, all aversion for the contrary doctrine dies in him.20

Fr. Michel Simoulin is a priest of the Society of Saint Pius X. He is currently District Superior of Italy. This article was heavily edited and abridged by Fr. Kenneth Novak.

1. Summa Theologica [hereafter ST] I, Q. 17, Art. 3.

2. ST, I, Q. 85, Art. 6, ad 1.

3. Romano Amerio, Iota Unum, pp. 262-63.

4. Ibid, pp. 264-65

5. Giovanni XXIII nel ricordo del segretario, Loris F. Capovilla (San Paolo, 1994), p. 122, n. 4.

6. Andrea Riccardi. Il Vaticano a Mosca (Laterza, 1992), pp. 268-69.

7. Letter of 9 May 1927 to Adelaide Coari, Giovanni XXIII, Profezia nella fedelta (Brescia, 1978), p. 427.

8. Carlo Falconi, Vu et entendu au Concile (Ed. du Roch, 1964), p. 124.

9. Letter of 27 July, "Mi Chiamero Giovanni," (Graphics and Arts, 1998), p. 306.

10. V. Soloviev, I tre dialoghi a il racconto dell'Anticristo (Marietti, 1996), pp. 168-170.

11. Alain Besançon, 30 Giorni, May 1988, p. 59.

12. Robert Hugh Benson, Il Padrone del Mondo (Jaca Boock), 1998, p. 140.

13. Iota Unum, pp. 464-466.

14. J. Guitton, Paolo VI segreto (Ed. Paoline, 1985), p. 152.

15. Il Concilio Vaticano II, Vol. I, Parte B, ed. P. Caprile (Ed. Civiltà Cattolica), p. 578.

16. Reported by M. D. Chenu in op. cit. p. 118.

17. Chiesa a Massoneria (Ed. Nardini, 1989).

18. M. D. Chenu, op. cit. p. 92.

19. H. Benson, loc. cit.

20. E. Hello, L'uomo (Paris, 1878).