The Guilds

|

Dr. Peter Chojnowski |

|

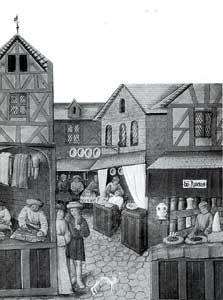

The shopping pavilion of a medieval town proffers its wares. Tailors snip and stitch, furriers array pelts, a barber shaves a customer as basins swing above his stall—utensils of a trade that included bloodletting and tooth pulling. Pastries scent a grocer's stall: his sign touts "good Hippocras," a spiced wine. Officials guarded buyers' rights, fined butchers who cut beef on boards last used for fish. Towns forbade work at night or in private: what a man might buy, he could see being made.

For us, in this credit-flushed capitalist economy, it is very difficult to conceive of a system of social and economic organization which is not constituted by an aggregation of single individuals into arbitrary and shifting "heaps," whether those heaps be "churches," "mutual funds," "political campaigns," "chat rooms," or "foster families." No one really "belongs" anywhere. We only temporarily "associate" with those who provide us with the means for the satisfaction of certain private desires or needs. Such a situation, more pronounced than ever, is the ultimate triumph of Liberalism.

Even though Enlightenment Liberalism conceived of the "good" and "liberated" society as just such an aggregation of "free" and "equal" individuals, it was the liberals of the 19th and 20th centuries who claimed that liberal man himself was divisible into distinct and often conflicting "desires," "impressions," "choices," and "dimensions." Who does not pass through this world, as it is presently arranged, and not feel a sense of being "emptied out" of personal life and spiritual substance? Just as liberal society, the liberal economic order, and the liberal state conquer the masses for the Total State by dividing them into isolated, detached, and rootless individuals, so too does the capitalist consumer economic order divide man into incongruous parts by visually immersing him in a world of advertisements which appeal to individual senses and, even, to distinct conscupiscible-ridden desires and urges. The ad campaign is really the driving motor of the capitalist society. The appeal to the groundless curiosity of a man, the false promise of glamour, beauty, acceptance, satiation, and a care-free leisure, can only leave a man "beside himself,"—beside himself with false hopes, living a mental life which is not his own. Our economy is powered by illusion, and ends in despair.

If the ad is the sign of the capitalist economy and the consumerist man who is "beside himself" with advertisement-induced desire, it is surely an indication of quite a different economic and social system when we discover that, as late as the 18th century, any attempt to lure a potential customer into one's own business, whether by ad or by verbal inducement, was strictly forbidden in France. This prohibition was in place prior to the dissolution of the guilds. 1

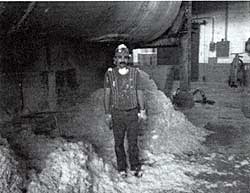

Bleaching rags at Parsons Paper Company, Holyoke, Massachusetts (1990)

Workers at Alcon Waste Industries, Holyoke, Massachusetts (1990)

Both the prohibition of advertisement and the existence of the guilds, as occupational brotherhoods dedicated to providing for the needs of the citizenry while also ensuring the livelihood and the personal and familial development of the members, were State- and Church-supported means of upholding a social organization which we can only refer to as organic and communal. The organic and communal structure of life and institutional organization was an expression of, and an inducement to, an integral and personal manner of existing. How does the prohibition of the ad indicate all of this? Primarily, the ad indicates the exaltation of the free choice of the individual over the economic need of workers and their families. By the flashy or enticing image, an individual is psychologically drawn to disregard the real needs of all the workers and families which are not part of the enterprise which is advertising. By being attracted, we become enveloped in our own desire for the product. "Enveloped" is the right word. In our encounter with the advertisement, we are surrounded and enclosed in our own urges, in our own egoistic need to provoke the envy of our neighbor. To buy without reference to and enticement by an ad, as was the norm in the Catholic Ages, is to approach a product in a totally different way than a product is approached in the Capitalist Age. In the Capitalist Age, a product is something which has been produced to appeal to whim and arbitrariness. There is a certain "recklessness" which attaches itself to every purchase. The producers and advertisers depend upon this recklessness. They know that when the contemporary customer buys a product, he does not care who has produced the product, under what conditions, for the ultimate financial benefit of whom, or whether by buying a cheap and mass-produced item we are overlooking a product which was crafted by a true artist. We are indifferent to the possibility that by buying a "low-cost" item, we may be undercutting the livelihood of a man and a family in need. It does not matter. The social implications of our purchases are non-existent. We act to satisfy our own need. The exotic and voluptuous advertisement causes us to forget artist, family, social economy, and investment of real work. Moreover, those who cannot advertise are finished.

It is the same Catholic society that rejected the ad, that also guaranteed the various monopolies of the merchant and craft guilds. To reject the ad and to support the guilds is to uphold the common good of society and the unified good of the worker. Here personal independence, pride of choice, and the recklessness of the arbitrary is sacrificed to the financial and familial good of those who produce; to the obligation to support a brother as he practices his craft; to the moral requirement that I pay a just price so that another may have a just wage. The legally sanctioned ad was the death knell of this coherent world of family, craft, brotherhood, security, and charity.

The Guilds: Medieval and Ancient

Much can be learned about the ethos which animated the guilds and the society which fostered them, by considering the origin of the word "guild" itself. Derived from the Anglo-Saxon word gildan, meaning "to pay," the word had a close affiliation to the concept of sacrifice. This etymological fact has lead scholars to trace the origin of the guilds to the sacrificial assemblies and banquets of the heathen Germanic tribes. Moreover, along with this concept of sacrifice and tribute to the gods, the ancient Teutonic origins of the Medieval guilds have led many to view the family as the ultimate origin of the guild, due to the importance of family relationship among the Teutonic nations. It was this spirit of association, uniting sacrifice, piety, work, and family which was fostered by the Catholic Church as soon as she spread her mantle over these rustic peoples .2

Though we have some knowledge of the social traits and institutions, both among the pagan Teutonic tribesmen and the imperial Romans, which might have served as the ultimate origins of what became the guilds of the Middle Ages in western and central Europe (the Byzantines, we know, had a flourishing guild system which directly evolved from the ancient Roman collegia),3 there are very few actual records detailing the historical institutions of the guilds that came to dominate city life throughout the medieval period. The historical documentation is sparse. A perusal of the Classical authors for some indication of an antique origin of the guilds and the "guild idea" yields very little. Since these Roman authors were not, generally, interested in economic or social history, we have only a few snippets of information from Livy, Cassius Dio, and Plutarch4 concerning the existence of the collegium, the Classical analogue of the Medieval guild. The Theodosian Code of the fifth century and the Code of Justinian from the sixth century are, however, informative concerning the existence, function, and structure of guilds, or collegia. The very word collegium (derived from conlegium) emphasizes in its etymology a group of people bound together by common rules or laws. The words corpus (body) and corporatio (an extension of the same word) were used, especially by the Severan jurists. These words were synonymous with the word sodalitas, the most common word for "social club." Such a word like sodalitas, also, described religious brotherhoods, which in turn were commonly referred to as collegia. What the ancient sources tell us about these Roman realizations of the natural desire for association in common undertaking is that they were organized groups comprised of people in a particular craft, trade, or line of business, devoted much effort to religious observance and banquets, were overwhelmingly plebeian in character, and became hereditary in character.5 In the same way as it became the common practice in the Medieval guild, the Roman collegium came to perpetuate its membership through encouraging sons to follow their fathers in the father's particular trade. Sons replacing fathers, what can be called the traditional approach to occupations, lent additional weight to the social cohesion in the various trades and, also, provided for a coherence, both social and psychological, in the life of men. Technological liberalism's termination of that father/ mentor-son/apprentice relationship is, without question, one of the great factors contributing to the social, economic, and personal incoherence of so many contemporary lives. It is difficult for us to conceive of the fact that for the greater number of centuries of civilized development, the family workshop was the norm.6

The historical problem, however, is this: even though Roman law as related to the college was the foundation for Byzantine labor organization (the Byzantines always considering themselves to be the successors of the Eastern Roman Empire), this same law had little or no relevance in the West. By the time the study and knowledge of Roman Law revived in western Europe in the late eleventh and twelfth centuries, the medieval guild had already developed its own structure and rules without the benefit of Roman examples. This stark historical fact argues against any continuity (except, perhaps, in southern France and parts of Italy) between the college and the guild. Subsequently, this historical fact would also argue for the conclusion that the "guild idea" and the "guild reality" are both products of the collective Catholic social and economic genius.

The opaque origins of the European guild system is disconcerting, however, on account of the fact that such historical ambiguity permanently veils the source of authority which authorized the guilds. Are the guilds purely voluntary institutions which were constituted because of the need for association and mutual protection of men and families engaged in the same trade? Or do they depend upon the Church or the State for their legitimation? If we can make a judgment in this matter, based upon the evidence available, it would appear that the guilds were voluntary associations formed for the mutual benefit of the members.7 These associations were encouraged by the Church and officially sanctioned by the State. The voluntary associations needed the Church, since most of the social life of the guild members was structured by the liturgies, devotions, and festivals of the Church.8 The guilds needed the State in order to receive its monopoly over the exercise of their specific trade in their particular city or region.9

Even amidst this dearth of information concerning the early formation of the guilds,"10 we do know that by the 600s A.D., the formation of guilds was mentioned in and sanctioned by the "Laws of Ina," as these were published in England, a nation which experienced some of the most advance development of the guilds during the medieval period. In England itself, you find, in this very early Medieval Period, the formation of a type of guild which best exemplifies the conceptual and experiential kernel which is buried beneath the commercial and "shop" appearances which surrounded the institutional reality during the High Middle Ages.

Known as the frith guilds ("peace guilds"), these were associations, voluntary in character, which assumed a corporate responsibility for the good conduct of their members, while also sharing a mutual liability with regard to the financial security of its members. These guilds, formed to be brotherhoods of men and not of workers, practiced many of the works of charity and sustenance towards their own members which would become the common fare of the craft guilds in the High Middle Ages. From almsgiving, to care of a sick brother, from insurance funds against losses and burial of their own dead, to providing Requiem Masses for the souls of their deceased members, the frith guilds were the institutionalization of two natural human urges directed by and suffused with the gift of supernatural charity, which only emanates from the bosom of Holy Church.11

It has been the guilds with an occupational and economic orientation, however, which have attracted the most attention from historians. One type of such guilds, the merchant guilds, were well established throughout western Europe by the High Middle Ages. As an indication of their prevalence, in England, by the year 1100, there was a merchant guild to be found in a town of any significant size. From what we know from the guild statutes of Berwick and Southhampton and the guild rolls of Leicester and Tomes, such guilds were presided over by one or two aldermen assisted by two or four wardens. These officers presided over the meetings of the society and administered its funds and estates. They were assisted by a council of 12 to 24 members.12 The merchant guilds of the Medieval Period possessed extensive powers, including a monopoly of all the trading which occurred in the town. This monopoly was bolstered and sustained by providing the merchant guilds with punitive powers, which included the ability to fine all traders who were not members of the guild for illicit trading and to inflict punishment for all breaches of honesty or offenses against the regulations of the guild. Here we must become aware of a very important historical fact. Our very concept of a "municipality," has its origin in the medieval merchant guilds. Being the original "burgesses" (i.e., those who held land within the town boundaries, whether they were merchants or holders of agricultural land), the members of the merchant guilds constituted the municipality as distinct from feudal lands. This founding share in the constitution of the medieval town was normally passed down by inheritance, the eldest sons of the guildsmen admitted to the guild as of right, while the younger sons of the burgesses paid a small fee for their inclusion.13

The Craft Guilds: Hierarchy of Working Brothers

Even though the details of the early origins of the craft guilds in western Europe and England are misty, we can identify a few early historical markers. In England, it was the weavers and the fullers who were the first to obtain royal recognition of their guilds. By 1130, they had guilds established in London, Lincoln, and Oxford.14 In northern France, the word gilde first appears in written accounts as early as the year 779.15 By the 600's, the first corporations (from corporatio or "body of men") were well-established in Italy. It is thought that, after the Germanic invasions of the fifth century, enough of the old Roman collegia must have been preserved to form the nucleus of a new organization which would slowly but steadily develop, under the tutelage of the Catholic Church, during the Medieval Period.16 Moreover, from a very early date in the Medieval Period, the Mining Guilds, formed in Saxony and Bohemia and called Brüdershaft, Gesellschaft, and Genossenschaft, played a very critical role in establishing and enforcing regulations which protected the welfare of the worker and his family. Such things as requiring hygienic conditions in the mines, ventilation of the pits, precautions against accident, accommodations for bathing, limiting the allotted hours of work, establishing an advancing scale of wages, and supplying the necessities of life for the families of members, would serve as models for guild regulations and humane working conditions into the Christian centuries.17 Moreover, it was in the German city of Cologne where we find, in 1149, the charter for the guild of weavers. This document is one of the earliest genuine notices of craftsmen explicitly forming a guild.18

Since the guildsmen were often the responsible parties within the great medieval towns and cities, it often fell upon the guilds to defend the towns and their surrounding area from external attack. In many a medieval local war, each guild would form into its own company. Many glorious victories were won by armies constituted by guildsmen, fighting as comrades shoulder to shoulder. Even though their places in the army were not held in esteem, indeed, the mounted knights often scornfully referred to them as the "foot." Nevertheless, the insignia of their profession were held in honor and proudly displayed on their banners in battle. Many a battle formation saw standards decorated with the miner's pick and the carpenter's saw fluttering proudly alongside the pennons which bore the heraldic lions of the knights. It is from these fighting units that the armorial bearings of the craftsmen originate, the same bearings which adorn windows and statuary niches in many a medieval and Renaissance church.19 Referring to the presence of such bearings on the stained glass windows of cathedrals, Godefoid Kurth states that, "when the sun lights up their brilliant colors, one seems to see, as it were, the workers themselves, transfigured by religion, resplendent in all the imperishable glory and magnificence of Christian toil."20

Apprentice, Journeyman, Master

The idea that a man needs to perform well the duties and functions imposed upon him by civil society, is one rooted in the ancient past. The more diversified and developed a society is, the more specialized will be the roles which men play in that society. To excel in a specific task, craft, or art which one is responsible for, was always considered an attribute of manhood. The very word the Germans used for "prowess," or prouesse in French, was manheit or manliness. It is very difficult to any longer conceive of a "master," a man who had within his mind and his flesh and his bones an "art," which one could only grasp after years of watching, speaking with, and, even, living with the master. In our age of "skills" employable by "human resources," it taxes the understanding to grasp the Medieval and Ancient conception of art (ars in Latin and techne in Greek). To fashion so as to create something well-made. To not follow "instructions," but to know how to do or make something. (I have always thought that a teacher, for example a philosophy professor, who could not, after being awakened at 3 a.m., give a lecture on the transcendental properties of being, for example, sine lecture notes, but cum Java, was not worth his salt.)

It is the position of the Apprentice (from apprendre, "to learn"), however, which particularly attracts our attention, since it appears to be a position which has its origin in the Catholic Medieval mind, rather than in the mind of Antiquity, and on account of the fact that such a condition of patient submission and consistent extended labor appears so foreign to the youth of our day. The average apprentice would remain in a condition of entire dependence upon his master for approximately three to ten years. The obligation taken on by the master in accepting an apprentice was great. This great responsibility required a man of sound moral character, for the master was not to serve as merely a "skills management consultant," but rather, he would also act as substitute father for the boy which he took on. He was to treat the boy as his own child. The master, therefore, needed to convince the officers of the guild that he was capable of the moral and professional education of the youth.21 As an indication of the public and social nature of this master/apprentice relationship, the contract of apprenticeship was sometimes signed in the presence of the assembly of the guild.22

The paternal, and yet, also, fraternal aspects of the master/apprentice relationship were revealed in the fact that the apprentice had to embody the same characteristics which one would want one's own son or brother to embody; namely, he had to be a Catholic and, normally, of legitimate birth. This "son" and "brother" was taken into the master's household, trained in religion and the life of virtue, guarded by "door and bolt," and trained to practice the master's art perfectly. Such was the "yoke" which the master bore. The apprentice, on his side, was bound to look at the master as his father, to honor him, to obey him, and to fulfill faithfully the clauses of his contract, and, finally, not to leave him before the time, usually four to five years, agreed upon.23 Facts which bring out the social character, the communal and vocational sense, of this relationship are, for example, that the apprentice paid the master nothing, not even for room and board and, in order that the master not neglect his duty to train the apprentice to be a master like himself, the master was forbidden to have more than a certain number of apprentices.24 In a very real way, the master's careful and consuming training of the apprentice was his greatest contribution to the commonweal and to the historical continuity of his art.

After these, sometimes long, years of careful training and diligent effort, the apprentice, now qualified to practice his particular trade, would set out as a journeyman (from journee or "day," the journeyman being someone who was hired by the day).25 This period in the life of the young craftsman traditionally lasted for one or two years. Intended to complete and vary the technical education of the youth, exposing them to innovations not found in their own region and facilitating the transmission of innovations through the youth to various parts of the realm, the "tour of France," as it was referred to in France and Belgium, allowed the boy, usually about 17 through 19 years old, to complete his education both as a man and as a craftsman. Now, required to leave his safe-haven of the master's household, the young journeyman bargained as a day laborer for employment. How much more invigorating and manly than the college campus of our day! Godefoid Kurth, in his work The Workingmen's Guilds of the Middle Ages [available from Angelus Press. Price: $3.00], gives us an enticing picture of these "tours" when he states:

Carrying on his back a knapsack containing his few belongings and beguiling the way with many a joyous song the young workman went from town to town, stopping where he found work or pleasure, then passing on to visit new parts where he found work or pleasure, then passing on to visit new parts, becoming acquainted as he went with men and things. A conscientious and honest workman had in that way a fruitful supplementary training which brought him into touch with the more varied and less well known side of his art. He was generally sure of a hearty welcome, for everywhere he went, companies of journeymen opened their ranks to him and made it their business to find him occupation. The masters were nothing loath to employ strangers once these had furnished proof of their professional education. Often the advent of a stranger brought new methods into the workshop and thus improved the traditional ones.26

Only those who have experienced the grim, cold indifference with which the contemporary capitalist economic system "welcomes" the newly "educated" graduate can understand the loss of such a happy system.

After the journeyman returned to his own district, he would enter into the service of a master, thereby, officially taking his place within the ranks of his own profession. Even though the journeyman would enter upon the work of his profession, this did not entail that the status of Master was attained thereby. To prove that one had mastered one's own craft, that one knew how to shape that which was other into a perfect form of its kind, the artisan needed to pass a series of examinations, similar to those taken at a university. The exam included a theoretical and practical section. The theoretical section consisted of questions put by the jury on the principle points connected with the profession. The practical part of the examination was, by far, the more important. The candidate had to make a masterpiece. The jury chose the task which was to be executed and watched over the execution of the same task. Upon successfully completing the task, the journeyman was received into the ranks of the master-craftsmen by taking an oath to faithfully keep the statutes of the guild. The privileges which accrued to this newly-won position were many. A master could open a workshop, employ a journeyman and apprentices, give himself up to the practice of his profession, and be committed to the attendance of guild meetings.27

There are two things which are extremely thought provoking in this outline of the position of the mastercraftsman and the realm of work and fraternity which he established in his workshop. First, once a craftsman had attained the level of "master," he had no other ambition other than to be worthy of the title. There was something final and authoritative about his position and his art. His work and skill had ennobled him with a dignity which was not only recognized by his contemporaries, but also was, in a very real way, recognized by all those of the same craft which had gone before him and would come after him. How many in our day can state the same? Not only do most of the "jobs" in our day have no precedent in preceding centuries, but, moreover, they will have no memory in a single decade. It surely must affect the psychological state of a man to work all his life and yet to be "master" of nothing. Isn't "Mastership" what masculinity is all about?

The second aspect of the guild and master/apprentice system which sets it apart so starkly from our own economic life and our own "employment system" is the fraternity which existed between master and "employee." Kurth describes the benefits of such a system when he states,

The immense distance which today separates the worker from the master was utterly unknown to the craftsman of the Middle Ages in many trades. Ordinarily the master had begun by being a craftsman himself; similarly the craftsman had every chance of becoming a master himself some day. Master and craftsman had worked together at the same task, in the same workshops, in the same brotherly deference to the sacred law of toil. They ate at the same table, often lived under the same roof, and in every way lived the greater part of their lives together. Their social standing was not appreciably different.28

The Guild: Our Catholic Economic Model

It is not surprising, since the guild system was the economic system in the Catholic Ages, that an attack upon the Church and the civilization to which she gave birth would also be an attack upon the guild system. This attack came with the French Revolution. It culminated in the Chapelier Law of June 1791. The first article of this Law, which foreshadowed the complete demise of the guild system in Catholic Europe, reads:

As one of the fundamental principles of the French Constitution is the annihilation of every kind of guild for citizens of the same status or profession, it is forbidden to re-establish them, under any pretext or in any form whatsoever.29

It was clear to those who advanced the self-interested agenda of economic liberalism, that such brotherhoods of workers would only render impossible the complete atomization of society which is the goal and end result of Liberalism.

In light of this antagonism between the Revolution and the guild system, and even the "guild idea," it should not surprise us that the popes of the last 130 years have advocated the re-establishment, in a contemporary context, of the social and economic organisms which formed and filled the lives of so many thousands in past ages. Pope Pius XI, in his encyclical Divini Redemptoris [available from Angelus Press], states:

Faithful to these principles, the Church has given life to human society. Under her influence arose prodigious charitable organizations, great guilds of artisans and workingmen, of every type. These guilds, ridiculed as 'medieval' by the liberalism of last century, are today claiming the admiration of our contemporaries in many countries who are endeavoring to revive them in some modern form."30

Let us try, in our own way, and in our own circumstances, to revive these bodies of workers, so that the Holy Catholic Faith can stride into and conquer the precious realm of human labor.

Dr. Peter E. Chojnowski has an undergraduate degree in Political Science and another in Philosophy from Christendom College. He also received his Master's Degree and doctorate in Philosophy from Fordham University. He is the father of four children and teaches for the Society of Saint Pius X at Immaculate Conception Academy, Post Falls, Idaho.

1. Amintore Fanfani, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Capitalism (New York: Sheet and Ward, 1935), p.73.

2. The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: The Encyclopedia Press, Inc., 1913), p. 66

3. Steven Epstein, Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), p. 26.

4. Plutarch, Life of Numa, 17. Plutarch wrote that Numa, the second king of Rome, was responsible for organizing eight artisan trades into colleges. Nothing is known about the internal organization or purpose of these colleges in the republican period. Cf. Jean Pierre-Waltzing, Etude historique sur les corporations professionalles chez les romains (Louvain, Belgium, 1895), 1: 334-341.

5. Epstein, Wage Labor and Guilds, pp. 10, 19.

6. Ibid., p. 20.

7. Catholic Encyclopedia, p. 66.

8. Ibid.

9. Godefroid Kurth, The Workingmen's Guilds of the Middle Ages, trans. Fr. Denis Fahey (Hawthorne, CA: Omni Publications, 1987), p. 44.

10. Epstein, Wage Labor and Guilds, p. 62.

11. Catholic Encyclopedia, p. 66.

12. Ibid., p. 66. Cf: Ashley, Introduction to English Economic History and Theory (London, 1888), I, 67.

13. Catholic Encyclopedia, p. 66.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid., pp. 71-72.

17. Ibid., pp. 69-71.

18. Ibid., p. 69.

19. Kurth, The Workingmen's Guilds, p. 47.

21. Catholic Encyclopedia, p.66.

22. Kurth, The Workingmen's Guilds, p. 48.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Catholic Encyclopedia, p. 66.

26. Kurth, The Workingmen's Guilds, p. 49.

27. Ibid., pp. 50-51.

28. Ibid., p. 55.

29. Ibid., p. 42.

30. Ibid., p. 39.