Was the "Good Pope" a Good Pope? Pt. 2

Part II

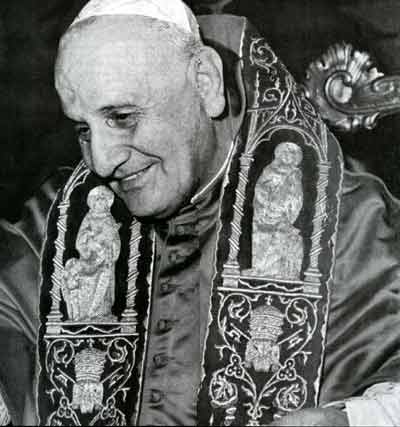

The series focuses on the principles expressed in Pope John XXIII's own writings by which he lived his life and reigned as pontiff. Last month The Angelus discussed the first of the four basic sophisms to which he adhered (see "Was the 'Good Pope' a Good Pope?" Sept. 2000).

This installment discusses the second, third, and fourth of those four sophisms. The article originally appeared in the Society of Saint Pius X's Italian publication, La Tradizione Cattolica (Anno XI, n. 2[43]-2000), and was translated by The Angelus.

2nd Sophism: Look For What Unites and Put Aside What Divides

On October 11, 1962, at his Inaugural Allocution of the Second Vatican Council, Pope John XXIII said:

[I]t is necessary first of all that the Church should never depart from the sacred patrimony of truth received from the Fathers. But at the same time she must ever look to the present, to the new conditions and new forms of life introduced into the modern world, which have opened new avenues to the Catholic apostolate.

For this reason, the Church has not watched inertly the marvelous progress of the discoveries of human genius, and has not been backward in evaluating them rightly...

[T]his having been established, it becomes clear how much is expected from the Council in regard to doctrine. That is, the Twenty-first Ecumenical Council, which will draw upon the effective and important wealth of juridical, liturgical, apostolic, and administrative experiences, wishes to transmit the doctrine, pure and integral, without any attenuation or distortion, which throughout twenty centuries, notwithstanding difficulties and contrasts, has become the common patrimony of men. It is a patrimony not well-received by all, but always a rich treasure available to men of good will.

The same optimism pervades all of the Inaugural Allocution of Pope John XXIII; that the new conditions and forms of life allow the Catholic Church to develop its apostolate in a manner better than before; that her doctrine was supposed to have become the "common patrimony of men" and therefore it is necessary to look at all that which is good and beautiful in the present without dwelling on that which can still constitute a difficulty, etc.

From several letters in his own hand and, further, his addresses, we can derive the basic mentality of Angelo Roncalli before and after his coronation to the papacy:

I remain with my old positions, namely, to believe with my eyes, to interpret everything as good, and I take pleasure in the good rather than diverting my attention excessively to the vision of evil, and then watching its taking place (March 20, 1932).1

Let us not dwell upon recollections of that which divides us: let every bitter word on our lips, every useless complaint be checked. Let us look at the future in light of the purpose of Christ (Jan. 25, 1935).2

Always preoccupied, excepting dedication to the principles of the Catholic creed and morals, more about that which unites than about that which separates and provokes disputes (March 15, 1953).3

Let us continue to love one another, to love one another so; and in the discussion let us persist in taking advantage of that which unites, by leaving aside, if there is, anything that would be able to detain us a little in difficulty.4

[I]t is heard by some that the Pope is too much of an optimist; he sees only the favorable side of things; he brings to light only the better part. Yes, he had this outlook; it is an attitude that he believes providential and it makes him similar to what Our Lord himself did, who wonderfully propagated positive and constructive teachings about himself, teachings bearing joy and peace (March 31, 1963).5

On the contrary, we find the predecessors of Pope John XXIII speaking very differently:

God forbid that the children of the Catholic Church should even in any way be unfriendly to those who are not at all united to us by the same bonds of faith and love. On the contrary, let them be eager always to attend to their needs with all the kind services of Christian charity, whether they are poor or sick or suffering any other kind of visitation. First of all, let them rescue them from the darkness of the errors into which they have unhappily fallen and strive to guide them back to Catholic truth, and to their most loving Mother who is ever holding out her maternal arms to receive them lovingly back into her fold. Thus, firmly founded in faith, hope, and charity and fruitful in every good work, they will gain eternal salvation. (Bl. Pope Pius IX, Quanto Conficiamur Moerore, Aug. 10, 1863)

Controversies therefore, they say, and long-standing differences of opinion which keep asunder till the present day the members of the Christian family, must be entirely put aside, and from the remaining doctrines a common form of faith drawn up and proposed for belief, and in the profession of which all may not only know but feel that they are brothers. The manifold churches or communities, if united in some kind of universal federation, would then be in a position to oppose strongly and with success the progress of irreligion. (Pope Pius XI, Mortalium Animos, Jan. 6, 1928 [available from Angelus Press. Price: $1.95])

Even on the plea of promoting unity it is not allowed to dissemble one single dogma; for, as the Patriarch of Alexandria warns us, 'Although the desire for peace is a noble and excellent thing, yet we must not for its sake neglect the virtue of loyalty in Christ.' Consequently, the much desired return of erring sons to true and genuine unity in Christ will not be furthered by exclusive concentration on those doctrines which all, or most, communities glorying in the Christian name accept in common. The only successful method will be that which bases harmony and agreement among Christ's faithful ones upon all the truths, and the whole of the truths, which God has revealed. (Pope Pius XII, Orientalis Ecclesiae, April 9, 1944)

"As regards the method to be followed in this work, the bishops themselves prescribed what ought to be done and what ought to be avoided: and they will demand that their prescriptions be observed by all. Likewise they will be on guard in order that, on the pretext that greater consideration could be given to what unites us than to what separates us from the non-Catholics, indifferentism, always a danger, is not encouraged, especially among those who are little instructed in theological matters and not practicing their religion very much.

"The conforming or accommodating of the Catholic teaching (in matters of dogma or truths connected with dogma) through a spirit, today called "irenical," to the doctrines of the dissidents (and this under the pretext of comparative study and through the vain desire of the progressive assimilation of the different professions of faith) in such a way that the purity of Catholic doctrine has to suffer from it, or the genuine and certain sense of it is obscured must, in fact, be avoided.

"The Catholic doctrine will therefore have to be proposed and exposed totally and integrally: what Catholic truth teaches about the true nature and means of justification, about the constitution of the Church, about the primacy of jurisdiction of the Roman Pontiff, about the only true union which is accomplished with the return of dissidents to the only true Church of Christ will not at all be obliged to be passed over in silence or covered with ambiguous words. Let it be taught to them that they, in returning to the Church, will lose no part of the good which, through the grace of God, hitherto has arisen in them, but which with their return this good will rather be completed and perfected. It is not necessary therefore to speak of this subject in a way such that they are to think they bring to the Church, with their return, one essential element that would have been lacking to it up to the present. These things must be spoken clearly and openly, both because they are looking for the truth, and because a true union cannot be achieved apart from the truth." (Pope Pius XII, Ecclesia Catholica, Dec. 20, 1949)

Response to the Second Sophism

It is enough to start with an excerpt of R. P. Tito Centi, O.P., who writes in his commentary on St.Thomas Aquinas's Summa Theologica:

[M]any have taken up falsifying the notion of peace, in ceasing to consider the purely negative side of [peace], namely the absence of conflicts or violent and outward attacks, through the forced acceptance of any order of things whatever. [St. Thomas Aquinas] will be able to point that out from the principle that, "Peace includes concord and adds something thereto." All these considerations are to be clearly pointed out, in order not to confuse the Christian aspiration for peace with a certain contemporaneous pacifism, which is the mask of a bleak utilitarian and materialist conception of life.6

St. Thomas goes on to say that wherever peace is, there is concord [i.e., agreement—Ed.], but there is not peace [necessarily—Ed.] wherever there is concord, if we give peace its proper meaning.

He explains:

Peace gives calm and unity to the appetite. Now just as the appetite may tend to what is good simply, or to what is good apparently, so too, peace may be either true or apparent. There can be no true peace except where the appetite is directed to what is truly good, since every evil, though it may appear good in a way, so as to calm the appetite in some respect, has, nevertheless many defects, which cause the appetite to remain restless and disturbed. Hence true peace is only in good men and about good things. The peace of the wicked is not a true peace but a semblance thereof, wherefore it is written, "[B]ut whereas they lived in a great war of ignorance, they call so many and so great evils peace (Wis. 14:22)" (Summa Theologica, II-II, Q. 29, A. 2, ad 3).

Furthermore, St. Thomas observes that "In like manner if there be concord as to goods of importance, dissension with regard to some that are of little account is not contrary to charity..." (ST, II-II, Q. 29, A. 3, ad 2).

"There is, in fact, a hierarchy among goods. Some goods are essential or principal, others are secondary or accidental. Only those apt for establishing friendship, unity, or peace, are principal goods. The Church is united by faith and charity; civil society by the common fatherland and the common good; the family by paternity; while humanity is united by the common nature of the human race. These goods are the principal goods that constitute each of the four communities.

"In every society secondary goods can be disregarded in order to look after the principal good alone. But neither unity nor peace can be established by looking to achieve only a few secondary goods, for example, a Catholic who wanted to disregard variances in the faith in order to establish a "peace" with non-Catholics by looking only at the unity of the human race. This peace would be false, indeed dangerous, because is was not rooted in the principal good which is faith and charity.

"In the case of the basis for converting the heterodox, the consideration of what unites us can be conceded to a uniquely secondary good even if there is dissent over the principal goods. St. Thomas Aquinas clearly teaches this.

"However, it is to be borne in mind, in regard to the philosophical sciences, that the inferior sciences neither prove their principles nor dispute with those who deny them, but leave this to a higher science; whereas the highest of them, namely, metaphysics, can dispute with one who denies its principles if only the opponent will make some concession; but if he concede nothing, it can have no dispute with him, though it can answer his objections. Hence Sacred Scripture, since it has no science above itself, can dispute with one who denies its principles only if the opponent admits some at least of the truths obtained through divine revelation; thus we can argue with heretics from texts in Holy Writ, and against those who deny one article of faith we can argue from another. If our opponent believes nothing of divine revelation, there is no longer any means of proving the articles of faith by reasoning, but only of answering his objections—if he has any—against faith. Since faith rests upon infallible truth, and since the contrary of a truth can never be demonstrated, it is clear that the arguments brought against faith cannot be demonstrations, but are difficulties that can be answered (ST, I, Q. 8, sed contra)."

If no discussion is possible, a certain concord can eventually be established, but it will have to be careful not to confuse that concord with peace. In fact, there is concord even among the demons, but there is no peace:

The concord of the demons, whereby some obey others, does not arise from mutual friendships, but from their common wickedness, whereby they hate men, and fight against God's justice. For it belongs to wicked men to be joined to and subject to those whom they see to be stronger, in order to carry out their own wickedness (ST, I, Q.109, A. 2, ad 2).

The same thing is verified among the adversaries of the Catholic Church, among whom there is always concord in order to strive to destroy it, but not peace.

3rd Sophism: We Must Catch Up with the Times and Express Doctrine in Modern Ways of Thinking

We only have to examine again Pope John XXIII's Opening Allocution of the Second Vatican Council to prove his belief in the third sophism:

"Our duty is not only to guard this precious treasure, as if we were concerned only with antiquity, but to dedicate ourselves with an earnest will and without fear to that work which our era demands of us, pursuing thus the path which the Church has followed for twenty centuries.

"The salient point of this Council is not, therefore, a discussion of one article or another of the fundamental doctrine of the Church which has repeatedly been taught by the Fathers and by ancient and modern theologians, and which is presumed to be well known and familiar to all.

"For this a Council was not necessary. But from the renewed, serene, and tranquil adherence to all the teaching of the Church in its entirety and preciseness, as it still shines forth in the Acts of the Council of Trent and First Vatican Council, the Christian, Catholic, and apostolic spirit of the whole world expects a step forward toward a doctrinal penetration and a formation of consciousness in faithful and perfect conformity to the authentic doctrine, which, however, should be studied and expounded through the methods of research and through the literary forms of modern thought. The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented is another. And it is the latter that must be taken into great consideration, with patience if necessary, everything being measured in the forms and proportions of a Magisterium which is predominantly pastoral in character.

"At the outset of the Second Vatican Council, it is evident, as always, that the truth of the Lord will remain forever. We see, in fact, as one age succeeds another, that the opinions of men follow one another and exclude each other. And often errors vanish as quickly as they arise, like fog before the sun. The Church has always opposed these errors."

In short, the Holy Father said the Catholic Church was not a museum. It knew its doctrine well, and, therefore, it was not a matter of repeating the teachings which had become by now the common patrimony of men. However, a new challenge had arisen to adapt it by using forms of modern thought while saving, however, the substance of the ancient doctrine. Theology must be updated to modern thought, and therefore broken loose from the classic mentality with which the Church was identified up until Vatican II.

Pope John XXIII noted (Oct. 10, 1958): "We are not here on earth to guard a museum, but to cultivate a garden flowering with life."7 Further, he stated on January 13, 1960: "The Catholic Church is not an archeological museum. It is the ancient fountain of the village that gives water to the generations of today, as it gave it to those of the past."8

A museum is a definite reality, closed and well-guarded, while a garden is open to all. Pope John XXIII advocated that the Church give up closing itself off within the formulas of its doctrine, and open itself to the new way of speaking of the present world. It must abandon words too strict and that indicate too many limits, in order to adopt "open" words more apt to welcome extraneous persons to the Catholic Church. Instead of speaking of the Catholic Faith, we will speak of its doctrine, of its thought, even the "opinion" of Catholics. For example, it is now said, "For Catholics, Christ is God!" Instead of charity, which is the love of the true and Catholic God, we will speak only of "love," or of "solidarity," or of "universal brotherhood." Instead of Christianity being rebuilt, we will speak of the duty of constructing a "civilization of love." Instead of the Church defined as the society of the Catholic faithful of Christ, we will say that the Church is "communion," the "assembly," or "the people of God."

Author Giuseppe Dossetti explains it in Il Vaticano II (1996):

Thus, the purely biblical terms of "communion" and of "assembly" have become typical of the new ecclesiology which has little by little at least been initiated, if not yet completely developed. They serve to point out, rather than the juridical bond, the intensity and universality of the vital spirit (afflatus) that unites all the members to Christ and among themselves ....They did not want to repeat word for word the equation [i.e., the identification—Ed.] of Mystici Corporis of Pius XII between the Catholic Church and the Body of Christ, since it was preferred to say not only that the Church of mystery is the Catholic Church, but also in the Catholic Church subsists the Church of mystery!

Dossetti gives us the ecumenical dimension of the phrase, "people of God":

The [phrase] "people of God" has a potentially universal extension, according to diverse orders: firstly the Catholics, who are 'fully' incorporated; then the baptized who do not profess the integral faith or who do not retain the unity of communion with the successor of Peter, but who are nevertheless still attached by the common possession of the Sacred Scriptures and by the other sacraments, the Eucharist included; then the non-Christians (Jews, Muslims, and others).9

Fr. Marie-Dominique Chenu, O.P., also rejoices at the Inaugural Allocution of John XXIII on account of "its criticism of the discussions on acquired doctrines, the verity of which ought only to be repeated, but formulated according to the needs of these times."10 A few years later, Chenu would take up the issue again:

The point is not to distinguish between an immovable "substance" and variable exterior forms....It is interiorly, through the fidelity itself of my faith, that I grasp the truth always identical and always new of the Mystery, today in action, in its very "substance," and not in the simple opportunistic adaptation of its formulas. A substance exacting, subtle and delicate, according to the paradigm of continuity, to "the measure of the unity of a living being" ("Ce qui change et ce qui demeure," in L'Eglise vers l'avenir [Paris, 1969], pp. 87-91; p. 91).11

On the contrary: Pope Pius IX in the Syllabus of Errors [available from Angelus Press] condemned the following affirmations:

No. 13: "The method and principles by which the old scholastic doctors cultivated theology are no longer suitable to the demands of our times and to the progress of the sciences"—condemned (Tuas Libenter, Dec. 21, 1863).

No. 80: "The Roman Pontiff can, and ought to, reconcile himself and come to terms with progress, Liberalism and modern civilization"—condemned (Allocution Jamdudum Cernimus, March 18, 1861).

Pope St. Pius X in Pascendi Gregis (Sept. 8, 1907) illustrated and condemned the methodology of the modernists:

To ascertain the nature of dogma, we [i.e., the modernists—Ed.] must first find the relation which exists between the religious formulas and the religious sense. This will be readily perceived by anyone who holds that these formulas have no other purpose than to furnish the believer with a means of giving to himself an account of his faith. These formulas therefore stand midway between the believer and his faith; in their relation to the faith they are the inadequate expression of its object, and are usually called symbols; in their relation to the believer they are mere instruments. Hence it is quite impossible [always according to the modernists—Ed.] to maintain that they absolutely contain the truth: for, in so far as they are symbols, they are the images of truth, and so must be adapted to the religious sense in its relation to man; and as instruments, they are the vehicles of truth, and must therefore in their turn be adapted to man in his relation to the religious sense. But the object of the religious sense, as something contained in the absolute, possesses an infinite variety of aspects, of which now one, now another, may present itself. In like manner he who believes can avail himself of varying conditions. Consequently, the formulas which we call dogma must be subject to these vicissitudes, and are, therefore, liable to change. Thus the way is open to the intrinsic evolution of dogma. Here we have an immense structure of sophisms which ruin and wreck all religion!...To conclude this whole question of faith and its various branches, we have still to consider, Venerable Brethren, what the Modernists have to say about the development of the one and the other. First of all they lay down the general principle that in a living religion everything is subject to change, and must in fact be changed. In this way they pass to what is practically their principal doctrine, namely, evolution. To the laws of evolution everything is subject under penalty of death—dogma, Church, worship, the Books we revere as sacred, even faith itself.

Pope Pius XII in Humani Generis (Aug. 12, 1950 [available from Angelus Press]):

"In theology, some want to reduce to a minimum the meaning of dogmas; and to free dogma itself from terminology long established in the Church and from philosophical concepts held by Catholic teachers, to bring about a return in the explanation of Catholic doctrine to the way of speaking used in Holy Scripture and by the Fathers of the Church. They cherish the hope that when dogma is stripped of the elements which they hold to be extrinsic to divine revelation, it will compare advantageously with the dogmatic opinions of those who are separated from the unity of the Church and that in this way they will gradually arrive at a mutual assimilation of Catholic dogma with the tenets of the dissidents.

"Moreover, they assert that when Catholic doctrine has been reduced to this condition, a way will be found to satisfy modern needs, that will permit of dogma being expressed also by the concepts of modern philosophy, whether of immanentism or idealism or existentialism or any other system. Some more audacious affirm that this can and must be done, because they hold that the mysteries of faith are never expressed by truly adequate concepts but only by approximate and ever changeable notions, in which the truth is to some extent expressed, but is necessarily distorted. Wherefore they do not consider it absurd, but altogether necessary, that theology should substitute new concepts in place of the old ones in keeping with the various philosophies which in the course of time it uses as its instruments, so that it should give human expression to divine truths in various ways which are even somewhat opposed, but still equivalent, as they say. They add that the history of dogmas consists in the reporting of the various forms in which revealed truth has been clothed, forms that have succeeded one another in accordance with the different teachings and opinions that have arisen over the course of the centuries."

Response to the Third Sophism

Again, the basic drift of the third sophism of Pope John XXIII is that it was necessary to express doctrine in modern ways of thinking. Professor Romano Amerio addressed this fallacy in his great analytical work of the Second Vatican Council, Iota Unum [available from Angelus Press. Price].

The updating of the formulas has been the explicit and formal cause of Vatican Council II, as the Pope who summoned it, John XXIII, proclaimed in his opening speech. This doctrine of distinguishing between the substance of the faith and the formulas with which the substance is expressed is a doctrine taught for the first time by John XXIII, it is a doctrine that did not exist before. Then it became a common doctrine, quite accepted by all, because no one wishes to recognize in it the shock resulting from the fact that different expressions mean the same as what is expressed.12

The formulas in which the Church expresses its doctrines are not a clothing, that is, an external covering; they are the expression of a naked truth. As the Latin text of the opening speech says, they are expressions of truth that have been received from God; it is impossible to maintain the sense of a proposition if one re-expresses it in terms that can be interpreted as having a different meaning. For example, if the formula expressing the Church's faith is: "The bread is transubstantiated into the Body of Christ," it is clear that the formula, "The bread is transfinalized into the Body of Christ," does not maintain the truth in question, because changing the finality of goal or destiny of something is altogether different from changing its substantial being. It is alleged that a new interpretation of the same faith is all that is being attempted, a case of new words for old. But since words are not neutral in meaning, nor a kind of hook on which any kind of idea can be hung, this process actually involves a movement from one meaning to another, a movement from truth to its denial.13

This should be evident to everybody, but the innovators are experts in the denial of the evident, which, not being demonstrable, is the easiest thing to deny. However, the consequences of the renunciation of the classic language of the Church have been exposed with severity by Italian Saverio Vertone who has spoken about the "sacred ruins":

We can ask ourselves how on earth for the first time in a thousand years it is no longer possible to point out to men that indefinite line of the horizon where earth and sky, the possible and the impossible, touch each other without being confused and dispelled in that perspective trompe-l'oeil [i.e., a style of painting that creates an illusion of reality—Ed.] that hinders us from respecting, on one side, the known and, on the other, the unknown.

The reason is simple. Not even the Church is pointing it out any longer, because the barrier of its symbols [i.e., doctrines—Ed.], of its rites, and of its religious values has collapsed. Perhaps Vatican II has only taken note of a caving in from below; but it has approved it and has transformed an ancient...and imposing religion into a sociology of the soul in which the spirit is nothing but the reduplication of the body. If transcendence was an illusion, today the whole of society experiences the collapse of the sky onto the earth and perceives how immanence condemns reality to blind tautology. The final collapse occurred when John XXIII tried to pursue society and conform religious language to the prevailing [culture]....It is of fact that the pulling down of the barrier has submerged every trace of transcendence under a uniform blanket of banalities that drive us to look for the meaning of life in life (as if life were something that can be touched and grasped with our hands), the soul in the stomach, the seed in the rind. Either there is no seed, or it is not there. And instead we are all looking for something that is not found on the spot in which we are digging, always deeper, in order to get hold of it. The wall of rites and of mysteries which have for 2000 years concealed the unknown, obliging us to respect it, having collapsed, everything has become known and senseless, and familiar reality itself has been transformed into a gigantic, banal enigma.14

4th Sophism: It Is Opportune To Employ Mercy Rather Than Severity and Condemnations

Again, we begin with Pope John XXIII's own words from his Inaugural Allocution of the Council:

The Church has always opposed these errors. Frequently she has condemned them with the greatest severity. Nowadays, however, the Spouse of Christ prefers to make use of the medicine of mercy rather than that of severity. She considers that she meets the needs of the present day by demonstrating the validity of her teaching rather than by condemnations. Not, certainly, that there is a lack of fallacious teaching, opinions, and dangerous concepts to be guarded against and dissipated. But these are so obviously in contrast with the right norm of honesty, and have produced such lethal fruits that by now it would seem that men of themselves are inclined to condemn them, particularly those ways of life which despise God and His law, or place excessive confidence in technical progress and a well-being based exclusively on the comforts of life. They are ever more deeply convinced of the paramount dignity of the human person and of his perfection as well as of the duties which that implies. Even more important, experience has taught men that violence inflicted on others, the might of arms, and political domination, are of no help at all in finding a happy solution to the grave problems which afflict them.

That being so, the Catholic Church, raising the torch of religious truth by means of this Ecumenical Council, desires to show herself to be the loving mother of all, benign, patient, full of mercy and goodness toward the brethren who are separated from her. To mankind, oppressed by so many difficulties, the Church says, as Peter said to the poor who begged alms from him: "I have neither gold nor silver, but what I have I give you; in the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, rise and walk" (Acts 3:6). In other words, the Church does not offer to the men of today riches that pass, nor does she promise them merely earthly happiness. But she distributes to them the goods of divine grace which, raising men to the dignity of sons of God, are the most efficacious safeguards and aids toward a more human life. She opens the fountain of her life-giving doctrine which allows men, enlightened by the light of Christ, to understand well what they really are, what their lofty dignity and their purpose are, and, finally, through her children, she spreads everywhere the fullness of Christian charity, than which nothing is more effective in eradicating the seeds of discord, nothing more efficacious in promoting concord, just peace, and the brotherly unity of all.

This fourth sophism in fact contains the following three individual premises, fastened together by the internal logic of Pope John XXIII: 1) The Church chooses mercy for today, having shown a visible lack of it in the past; 2) All men, in fact, have the sense of good and evil, and, having today chosen the path of the good with undivided hearts, are of goodwill; 3) It is not necessary, therefore, to put in the first place the preaching of doctrine because it can be a source of division; it is enough to offer charity to all.

[Understand that this "charity" is a falsification of true charity.-Ed.]

On the contrary: We oppose this false logic with excerpts from the predecessors of Pope John XXIII:

But, although we have not omitted often to proscribe and reprobate the chief errors of this kind, yet the cause of the Catholic Church, and the salvation of souls entrusted to us by God, and the welfare of human society itself, altogether demand that we again stir up your pastoral solicitude to exterminate other evil opinions, which spring forth from the said errors as from a fountain. Which false and perverse opinions are on that ground the more to be detested, because they chiefly tend to this, that that salutary influence be impeded and (even) removed, which the Catholic Church, according to the institution and command of her Divine Author, should freely exercise even to the end of the world—not only over private individuals, but over nations, peoples, and their sovereign princes; and (tend also) to take away that mutual fellowship and concord of counsels between Church and State which has ever proved itself propitious and salutary, both for religious and civil interests. (Bl. Pope Pius IX, Quanta Cura, Dec. 8, 1846)

|

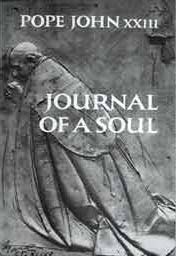

The principles of Pope John XXIII which are being analyzed in this three-part series are taken from his own book, Journal of a Soul (published in 1964). Of this book Pope John XXIII wrote, "My soul is in these pages."

|

|

We wish to draw your attention, Venerable Brethren, to this distortion of the Gospel and to the sacred character of Our Lord Jesus Christ, God and man, prevailing within the Sillon and elsewhere. [The Sillon was a group based in France attempting to make the Catholic Church more appealing to unbelievers by falsely democratizing her. The movement was condemned by Pope St. Pius X in this letter titled Notre charge apostolique, otherwise known as Our Apostolic Mandate, which is available from Angelus Press. —Ed.] As soon as the social question is being approached, it is the fashion in some quarters to first put aside the divinity of Jesus Christ, and then to mention only His unlimited clemency, His compassion for all human miseries, and His pressing exhortations to the love of our neighbor and to the brotherhood of men. True, Jesus has loved us with an immense, infinite love, and He came on earth to suffer and die so that, gathered around Him in justice and love, motivated by the same sentiments of mutual charity, all men might live in peace and happiness. But for the realization of this temporal and eternal happiness, He has laid down with supreme authority the condition that we must belong to His Flock, that we must accept His doctrine, that we must practice virtue, and that we must accept the teaching and guidance of Peter and his successors. Further, whilst Jesus was kind to sinners and to those who went astray, He did not respect their false ideas, however sincere they might have appeared. He loved them all, but He instructed them in order to convert them and save them. Whilst He called to Himself in order to comfort them, those who toiled and suffered, it was not to preach to them the jealousy of a chimerical equality. Whilst He lifted up the lowly, it was not to instill in them the sentiment of a dignity independent from, and rebellious against, the duty of obedience. Whilst His heart overflowed with gentleness for the souls of goodwill, He could also arm Himself with holy indignation against the profaners of the House of God, against the wretched men who scandalized the little ones, against the authorities who crush the people with the weight of heavy burdens without putting out a hand to lift them. He was as strong as he was gentle. He reproved, threatened, chastised, knowing, and teaching us that fear is the beginning of wisdom, and that it is sometimes proper for a man to cut off an offending limb to save his body. Finally, He did not announce for future society the reign of an ideal happiness from which suffering would be banished; but, by His lessons and by His example, He traced the path of the happiness which is possible on earth and of the perfect happiness in heaven: the royal way of the Cross. (Pope St. Pius X, Notre charge apostolique, Aug. 5, 1910)

These pan-Christians who turn their minds to uniting the churches seem, indeed, to pursue the noblest of ideas in promoting charity among all Christians: nevertheless how does it happen that this charity tends to injure faith? Everyone knows that John himself, the Apostle of love, who seems to reveal in his Gospel the secrets of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and who never ceased to impress on the memories of his followers the new commandment "Love one another," altogether forbade any intercourse with those who professed a mutilated and corrupt version of Christ's teaching: "If any man come to you and bring not this doctrine, receive him not into the house nor say to him: God speed you" (II Jn. 10). For which reason, since charity is based on a complete and sincere faith, the disciples of Christ must be united principally by the bond of one faith. Who then can conceive a Christian Federation, the members of which retain each his own opinions and private judgment, even in matters which concern the object of faith, even though they be repugnant to the opinions of the rest? And in what manner, We ask, can men who follow contrary opinions, belong to one and the same Federation of the faithful? (Pope Pius XI, Mortalium Animos, Jan. 6, 1928)

Response to the Fourth Sophism

Our reply comes by way of St. Thomas Aquinas and the Catechism of St. Pius X [available from Angelus Press. —Ed.] to answer whether it can be said strictly without distinctions that, "It is opportune to employ mercy rather than severity and condemnation."

Charity signifies not only the love of God, but also a certain friendship with Him; which implies, besides love a certain mutual return of love, together with mutual communion....Wherefore, just as friendship with a person would be impossible, if one disbelieved in, or despaired of, the possibility of their fellowship or familiar colloquy; so too, friendship with God, which is charity, is impossible without faith, so as to believe in this fellowship and colloquy with God, and to hope to attain to this fellowship. Therefore charity is quite impossible without faith and hope. (ST, I-II, Q. 65, A. 5).

Charity is not any kind of love of God, but that love of God by which He is loved as the object of bliss, to which object we are directed by faith and hope. (ST, I-II, Q. 65, Art. 5, ad l)

In the Catechism of St. Pius X, authored by the sainted pope himself, who was so strong against modernism, from the section titled, "The Main Virtues and Vices," subtitled "The Works of Mercy,"15 we read:

Q. What are the good works concerning which a particular account will be asked of us on the Day of Judgment?

A. The good works concerning which a particular account will be asked of us on the Day of judgment are the works of mercy.

Q. What is meant by a work of mercy?

A. A work of mercy is a work by which we help our neighbor in his spiritual or corporal needs.

Q. What are the spiritual works of mercy?

A. 1) to give counsel to those in doubt; 2) to teach the ignorant; 3) to admonish sinners; 4) to console the afflicted; 5) to forgive offenses; 6) to bear patiently with persons who are difficult; 7) to pray to God for the living and the dead. [Emphasis ours.]

Regarding the spiritual work of mercy, "to admonish sinners," a commentator on the Catechism of St. Pius X tells us that: "...as we are obliged to give alms to the poor in grave and urgent necessity, so we have the duty to aid sinners with fraternal correction, by helping them to escape the supreme evil of eternal damnation. No one, more than the sinner, has need of being corrected and led back to the good path with love and fraternal charity."16

In his Summa Theologica, St. Thomas teaches:

The reproof of the sinner, as to the exercise of the act of reproving, seems to imply the severity of justice, but, as to the intention of the reprover, who wishes to free a man from the evil of sin, it is an act of mercy and loving kindness, according to Proverbs 27:6: "Better are the wounds of a friend, than the deceitful kisses of an enemy." (ST, II-II, Q. 32, Art. 2, ad 3)

The correction of the wrongdoer is a remedy which should be employed against a man's sin. Now a man's sin may be considered in two ways: first as being harmful to the sinner, secondly as conducing to the harm of others, by hurting or scandalizing them, or by being detrimental to the common good, the justice of which is disturbed by that man's sin. Consequently the correction of a wrongdoer is twofold, one which applies a remedy to the sin considered as an evil of the sinner himself. This is fraternal correction properly so called, which is directed to the amending of the sinner. Now to do away with anyone's evil is the same as to procure his good; and to procure a person's good is an act of charity, whereby we wish and do our friend well. Consequently fraternal correction also is an act of charity because thereby we drive out our brother's evil, viz., sin, the removal of which pertains to charity rather than the removal of an external loss, or of a bodily injury, in so much as the contrary good of virtue is more akin to charity than the good of the body or of external things. Therefore fraternal correction is an act of charity greater than the healing of a bodily infirmity, or the relieving of an external bodily need.

There is another correction which applies a remedy to the sin of the wrongdoer, considered as hurtful to others, and especially to the common good. This correction is an act of justice whose concern it is to safeguard the rectitude of justice between one man and another. (ST, II-II, Q. 33, sed contra)

The good bear with the wicked by enduring patiently, and in due manner, the wrongs they themselves receive from them: but they do not bear with them so as to endure the wrongs they inflict on God and their neighbor. For Chrysostom says: "It is praiseworthy to be patient under our own wrongs, but to overlook God's wrongs is most wicked." (ST, II-II, Q. 108, A.1, ad 2).

Fortitude disposes to vengeance by removing an obstacle thereto, namely, fear of an imminent danger. Zeal, as denoting the fervor of love, signifies the primary root of vengeance, in so far as a man avenges the wrong done to God and his neighbor, because charity makes him regard them as his own. Now every act of virtue proceeds from charity as its root, since, according to Gregory (Hom. xxvii in Ev.), "There are no green leaves on the bough of good work, unless charity be the root." (ST, Q. 108, A. 2, ad 2)

Again, we turn to Romano Amerio in his Iota Unum:

The attitude to be adopted in regard to error is on the other hand a definite novelty, and is openly announced as being a new departure for the Church. The Church, so the Pope says, is not to set aside or weaken its position to error, but "she prefers today to make use of the medicine of mercy, rather than of the arms of severity." She resists error "by showing the validity of her teaching, rather than by issuing condemnations." This setting up of the principle of mercy as opposed to severity ignores the fact that in the mind of the Church the condemnation of error is itself a work of mercy, since by pinning down error those laboring under it are corrected, and others are preserved from falling into it. Furthermore, mercy and severity cannot exist properly speaking, in regard to error, because they are moral virtues which have persons as their object, while the intellect recoils from error by the logical act that opposes a false conclusion. Since mercy is sorrow at another's misfortune accompanied by a desire to help him (ST, II-II, Q. 30, A. 1), the methods of mercy can only be applied to the person in error, whom one helps by confuting his error and presenting him with the truth; and can never be applied to his error itself, which is a logical entity and cannot experience misfortune.

Moreover, the Pope reduces by half the amount of help that can be offered, since he restricts the whole duty of the Church regarding the person in error to the mere presentation of the truth: this is alleged to be enough it itself to undo the error, without directly opposing it. The logical work of confutation is to be omitted to make way for a mere didascalia (direct instruction) on the truth, trusting that it will be sufficient to destroy error and procure assent.

This papal teaching constitutes an important change in the Catholic Church, and is based on a peculiar view of the intellectual state of modern man. The Pope make the paradoxical assertion that men today are so profoundly affected by false and harmful ideas in moral matters that "at last it seems men of themselves," i.e., without refutations and condemnations, "are disposed to condemn them; in particular those ways of behaving which despise God and His law." One can indeed maintain that a purely theoretical error will cure itself, since it arises from purely logical causes; but it is difficult to understand the proposition that a practical error about life's activities will cure itself, since that sort of error arises from judgments in which the non-necessary elements of thought are involved. This optimistic interpretation of events, asserting that at last error is about to recognize and correct itself, is difficult enough to accept in theory; but it is also bluntly refuted by facts. Events were still maturing at the time the Pope spoke, but in the following decade they came to full fruition. Men did not change their minds regarding their errors, but became entrenched in them instead, and gave them the force of law. The public and universal acceptance of these errors became obvious with the adoption of divorce and abortion. The behavior of Christian peoples was entirely altered thereby, and their civil legislation, until recently modeled on canon law, was changed into something completely profane, no longer having a shade of the sacred about it. On this point, papal foresight indisputably failed.17

Once heretics...were burned. We say only that they ought to be dismissed, to be silenced. If one of these erring persons is a university professor in theological science, we remove him.

The most significant example of this serious desistance is seen in the case of Hans Kung. He should have been deprived of his chair. On the contrary, the authorities summoned to judge his case limited themselves to saying that he is not a Catholic theologian; yet he continues to have the qualification of Catholic theologian, he continues to propagate, to teach, to defend, to publicize, to expose his erroneous opinions in Catholic bookstores. But error is more contagious than truth, and more attractive....

At one time there used to be the titles of "heretic," of "suspected of heresy," of "intensely suspected," of the author of opinions which are "offensive to pious ears," and formulas of that kind; but a qualification through which a theologian continues to be allowed on the chair of theology, while nevertheless taking away the name, is an unjust position, and also incongruous. It would be like saying: We will allow this doctor who poisons patients to exercise medicine, but we must understand that he is no longer a doctor. On the contrary, it was the work that should have been prohibited, not the vocabulary.

Therefore, in this passage from the Letter [Tertio Millennio Adveniente, §361, disobedience is well-designated, and it is true, but it has remained silent about the ultimate cause of this disobedience, which is, precisely, the breviatio manus [the "foreshortening of the arm"] of the very government of the Church, its desistance, instigated explicitly by John XXIII, in the opening speech of the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council: "The Spouse of Christ nevertheless prefers today to make use of the medicine of mercy, rather than of severity: She deems to speak to the needs of today by demonstrating the validity of her doctrine rather than by her condemnation."

Here we cannot omit a luminous fact, and that is that error must be refuted properly by a work of mercy which is performed towards the one erring, who, in his error, is rendered unhappy. In fact, in the Gospel according to Matthew, Jesus says: "You are the salt of the earth" (Mt. 5:13). Salt seasons food; salt preserves foods otherwise perishable; salt disinfects wounds; for a moment it burns, but then it heals. Jesus does not say: "You are honey," but He says: "You are salt," exactly on account of its peculiar quality of being irreplaceable, which He Himself emphasizes. But to say that the Church "takes the way of mercy towards error," is to adopt incongruous terms: mercy is a virtue which is activated in the face of the wretchedness of men. It is often forgotten that, conversely, severity is a work of love. Holy Scripture is illuminating here also: "Such as I love, I rebuke and chastise. Be zealous therefore, and do penance" (Apoc. 3:19). And severity is such a work of love that we must, in order to be severe, force our nature, just as we must force it when we want to exercise the virtue of love. Because it is a matter of this: of exercising virtuous and supernatural love, not human love, not merely natural love. The force that we realize is exercised on our soul in order to perform acts just in severity and just in mercy, all these things to which our soul, of itself, is not inclined.18

In conclusion, let us note that in the new Catechism of the Catholic Church (1992), the third spiritual work of mercy, "to admonish sinners," is not even mentioned:

2447. The works of mercy are charitable acts with which we aid our neighbor in his corporal and spiritual necessities. Instructing, counseling, consoling, comforting, are spiritual works of mercy, as are forgiving and bearing wrongs patiently.

Rev. Fr. Michel Simoulin, a Frenchman, is a priest of the Society of Saint Pius X. He is currently District Superior of Italy.

1. Letter of March 20, 1932, cited by Leone Algisi, Giovanni XXIII (Marietti, 1959), p. 345.

2. Homily of January 25, 1935, at Istanbul, in La predicazione a Istanbul edited by A. Melloni (Florence, 1953), p. 55.

3. Homily of March 15, 1953, at Venice in, Giovanni XXIII profezia nella fedelta (Queriniana, 1978), p. 207.

4. Giovanni XXIII il concilio della speranza (Padua, 1985), p. 292.

5. Homily at the Church of St. Basil in Rome in, Giovanni XXIII transizione del Papato a della Chiesa (Borla, 1988), p. 170.

6. R. P. Tito S. Centi, O.P., Commento alla Summa Theologica, II-II, Q. 29, A. 1.

7. Mi chiamero Giovanni (L. Capovilla-Graphics and Art, 1998), p. 121.

8. Homily of January 13, 1960 in, Il Concilio della speranza, p. 141.

9. Giuseppe Dossetti, Il Vaticano II, (Il Mulino, 1996), p. 210.

10. Fr. Marie-Dominique Chena, O.P., Diario del Vaticano II (ll Mulino, 1996), p. 70.

11. Ibid., n. 34.

12. Stat Veritas, note 55 ( Milan: Ed. Ricciardi, 1997), p. 137.

13. Romano Amerio, Iota Unum (Kansas City: Ed. Sarto House, 1996), p. 544.

14. "Le Sacre Macerie" in Paralleli, n. 10, Dec. 1992, p. 122.

15. The Catechism of Pope Pius X, from the 1910 Dublin Edition (Gladysdale Vic., Australia: Instauratio Press, n.d.), pp. 170-171.

16. Spiegazione del Catechismo di S. Pio X (Ed. Paoline, 1963), pp. 388-389.

17. Amerio, Iota Unum, pp. 80-82.

18. Amerio, Stat Veritas, note 33, pp. 92-93.