The Nature of Catholic Leadership

"Lord, Thou knowest that I am not an ephemeral glory, but only the Glory of Thy Name." —St. Ferdinand of Castile, King and Confessor

With the whole Saracen army fronting his men awaiting to attack, the Norman knight, Robert Guiscard, admonished his soldiers to embolden their doubtful hearts and fight courageously against the overwhelmingly superior numbers of the enemy:

Our trust in God is more than in mere numbers. Fear not, the Lord Jesus Christ is with us! As He said: "If your faith is only the size of a mustard seed it is still enough to move mountains." Through the steadiness of our faith, the flame of the Holy Spirit, and in the name of the Blessed Trinity, we shall drive away this mountain, composed not of stones and earth but a filth of heresy and like corruption. Let us now purge ourselves of sin through confession and penitence, and receive the body and blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and prepare our souls. Because the strength of God will enable us, a small but faithful band, to overcome the multitude of the faithless.

The historian, Amatus of Montecassino, comments: "And so it was done. Everyone crossed themselves, raised their standards on high and began to fight. But God fought for the Norman, Christian host. He was their salvation, overthrowing and destroying the infidels."

To the mind of a 21st-century observer, it is immediately noticeable that Guiscard relied not on a technological edge over his enemies but rather on the steadfastness of his faith. Sheer romanticism? Fanatic lunacy? Or, is this a consequence of a clear-minded and sound understanding of the reality of man and of his destiny?

This single historical example sums up Catholic teaching about leadership better than many books. Such an act as we have recounted here can oftentimes demonstrate the essence of a matter better than many words, but for a clearer understanding an investigation of its principles is required. That is what we propose to do in this article.

In a nutshell, we can say that the nature of leadership is a form of the exercise of power. As with all other human activities, leadership is oriented to an end, and the legitimacy of its exercise derives from the goodness or truth of that end-principle towards which it tends. The identification of the proper end of leadership can be gathered from the endeavors of leaders such as King David and King Ferdinand, both of whom are glorified by the Church as saints because of their roles as leaders of their peoples as much as for their personal virtue.

St. Thomas Aquinas tells us that: "The lack of proper orientation of political power to its true end, as well as a correlative orientation towards an apparent good [or false elective end] results in injustice."1

We are left to conclude, therefore, that if the exercise of power is not oriented towards its proper end it disqualifies itself as a valuable behavior and a source of obligation for the citizens affected. It takes some thinking through to prove this important and perhaps startling point, but it is necessary to do so because it is the cornerstone of true political science.

It is self-evident that absolute Good is only God, ...and it reasonably follows that all creatures are only good insofar as they participate in the goodness of God.

We must start where St. Thomas Aquinas starts. To get where we are going, St. Thomas first treats of two important concepts signified by words much-abused today: Good and Dignity. According to his definitions, Good is that which is perfect, and hence the object of love. So, when describing that which is good we must keep in mind two principal notions: first, the Good is that which totally actualizes its form, that is to say, that which cannot be improved upon, or, in other words, is perfect, and this is God alone; and, second, that goodness is the act of be-ing of something "good." This is to say that something can be good in only a limited fashion: we would call it "partly" good. On the other hand, that which is whole perfectly according to its own genre we would call "plainly" good. For example, a hunting dog which would have all the attributes of its particular breed developed to perfect maturity would be a plainly good dog. On the other hand a dog that would track and point well but lack a keen nose would be a partly good dog. The same example works with categories of created things. It is self-evident that absolute Good is only God, because only God is perfect Act of Be-ing, and it reasonably follows that all creatures are only good insofar as they participate in the goodness of God.

It is said that "Goodness is self-diffusive," meaning that the possession of Good [i.e., God who is Goodness] is a participation in Goodness which "gives Itself away." The more one possesses Goodness, the more perfect he becomes. This is what is meant by saying that Good is also perfective. This perfective ability grows in intensity and extension as the rank of the Good possessed or desired increases within a hierarchy whose apex is God. The place or rank which each created thing possesses in the order of beings is what we properly call its dignity. For instance, the dignity of a plant is higher than that of a stone, that of an animal more than a plant, of man more than an animal. It is evident that there is no true dignity outside the perfective order of God and His One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church.

Following this line of reasoning, it can be concluded that something is good and worthy (i.e., endowed with dignity) when properly oriented towards its end. If it is dislodged from its relationship with its proper end, it becomes bad and devoid of any claim to dignity. A case in point is human free will: when used to choose what is good for salvation and the possession of God in the beatific vision, it is obviously a good thing with the highest dignity within Creation, but when used to choose the slavery of sin, free will becomes pitifully unworthy.

In summary, to be good is to have attained maximum perfection and be oriented to the proper end. We can also conclude that from goodness is derived all true dignity and that this goodness depends on both positing the right end and properly identifying the means which bring about that end.2

Applying these summary distinctions to the notion of leadership, we can surmise that a leader derives legitimacy (and with it a claim to be followed) only from his goodness, which is to say his perfective ability among other men. A leader's goodness increases in proportion to the greatness of his virtues, in particular those specific to his function. Aristotle says: "To be a virtuous State is to be a State in which those citizens who share in the government are virtuous; and in the State we are now discussing all citizens share in the government."3

This is why, yellow press aside, the public instinct of rejecting leaders of dubious personal morality is the right thing to do. This is why the political survival of Bill Clinton in spite of multiple accusations of personal immorality is a grave symptom of decomposition in the political system in the US. We have come a long way from the times of King St. Ferdinand of Castile (ca. 1199-1252): "I fear more the curse of an old woman [because of my injustice—Ed.] than all the armies of the Saracens."

Having achieved the degree of perfection allowed to us in this world, he became a source of perfection for his subjects through the administration of justice, by the promulgation and enforcement of just laws, and by the perfective force of his own virtue.

According to the introduction to the Feast of St. Ferdinand in the Roman Missal in use in Spain4, he was:

acknowledged by the Council at the age of 20 years, (and devoted the whole of his efforts to secure happiness for his subjects and to extend the borders of Christendom. He never unsheathed his sword against another Christian State. After having achieved domestic peace he led a series of prodigious military campaigns which exterminated Muslim power in Andalusia. The kingdoms of Baeza, Cordoba, Jaen, Murcia, and Seville surrendered one after another, and even Granada agreed to pay homage to his power. The glory of God and the triumph of the Cross were the only incentive for his efforts....At the same time he endeavored with equal eagerness to make justice to all of his subjects, ...fostered literature, endowed teachers, gave new life to the University of Salamanca, codified the old laws, and built the most beautiful cathedrals of Castile, in Burgos, in Toledo, in Leon, in Osma, in Palencia....

King Ferdinand was one of the finest examples of what a good leader must be to his people. The love of his kinsfolk carried him for generations in song as a model and in prayers as a saint. He was a good leader precisely because he was a saint. Having achieved the degree of perfection allowed to us in this world, he became a source of perfection for his subjects through the administration of justice, by the promulgation and enforcement of just laws, and by the perfective force of his own virtue. And having sought first the Kingdom of God and His perfect justice, Spain received glory and prosperity besides.5

It is paradoxical to our contemporaries that a king who spent the better part of his life sword in hand, bloodied to the hilt in hundreds of battlefields, could be at all a saint. Surely he does not fit the lame and languid picture of sanctity that New-Age artists create for us in their imagery. How could this soldier who stormed the watchtowers of Seville be a saint? By definition, sanctity means perfection and wholeness of life, and these are achieved in the exercise of the specific duties of state chosen for men by Divine Providence. It is the duty of a political leader to take his people to war when justice so demands it, and if done with the right intention fighting can indeed be a way of sanctification. In fact this proportion between spiritual and military life is expressed over and over again from the Book of Job through the Epistles of St. Paul, and is echoed in the writings of the Fathers of the Church. Which virtues are necessary to a leader to comply with his duty of state?

First of all, my son, you are to fear God; for therein lies wisdom, and being wise, you cannot go astray in anything....

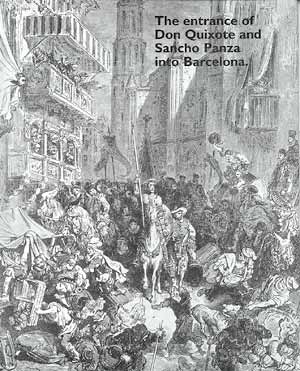

In the story given us by Miguel de Cervantes, his Don Quixote character beautifully summarizes what amounts to the Catholic teaching as he and his side-kick, Sancho Panza, prepare to take over the government of the Island Barataria. After reminding Sancho that he receives office from Heaven and not through any merit of his own, Quixote, the Knight of the Sad Figure speaks: "First of all, my son, you are to fear God; for therein lies wisdom, and being wise, you cannot go astray in anything. And in second place, you are to bear in mind who you are and seek to know yourself....Knowing yourself you will not be puffed up, like the frog that sought to make himself as big as the ox."6

|

Stained glass window in the cathedral of Seville depicting King St. Ferdinand seated on his throne with the symbols of royalty |

After establishing both the origin of authority in God and the sinful nature of man which should make us humble, Don Quixote takes this line of thought one step further and reinforces the intimate association between virtue and dignity we have established earlier in this article:

Look to humility for your lineage, Sancho....Pride yourself more on being a good man and humble than on being a haughty sinner....Remember, Sancho, that if you employ virtue as your means and pride yourself in virtuous deeds, you will have no cause to envy the means possessed by princes and noble lords; for blood is inherited but virtue is acquired, and virtue by itself alone has a worth that blood does not have.6

On the strength of this doctrine, the low nobility of Spain—her gentlemanry—won its right to a share in political authority, as it would in America, with virtuous deeds performed for the greater glory of God in the service of the King.7 As if to crown the discourse with a jewel of classical thinking, Don Quixote walks in the footsteps of Aristotle, Cicero, and St. Thomas and muses about largeness of soul, about magnanimity:

Never be guided by arbitrary law, which finds favor only with the ignorant who plume themselves on their cleverness. Let the tears of the poor find more compassion in you, but not more justice, than the testimony of the rich. Seek to uncover the truth amid the promises and gifts of the man of wealth as amid the sobs and pleadings of the poverty-stricken....If the rod of justice is to be bent, let it not be by the weight of a gift but by that of mercy. When you come to judge the case of someone who is your enemy, put aside all thought of the wrong he has done to you and think only of the truth. Let no passion blind you where another's rights are concerned....Abuse not by words the one upon whom punishment must be inflicted; for the pain of the punishment itself is enough without the addition of the insults....And insofar as you may be able to do so without wrong to the other side, show yourself clement and merciful; for while the attributes of God are all equal, that of mercy shines brighter in your eyes than does that of justice.6

The good ruler wins eternal reward in heaven,8 and by his behavior earns the trust of his fellows and the obedience of his subjects:

If there be someone who is superior in virtue and in ability to perform the best actions, it is noble that we should follow him. And such a man should have not only virtue, but also the power to act according to virtue.9

"He maketh a man who is a hypocrite to rule because of the sins of the people" (Job 34:30).

Plato compares the true politician to a wise weaver who lovingly assists in fashioning the fabric of behaviors and interests that makes public life. He weaves this tapestry with the bonds of the knowledge of truth and the love of the Good, firmly tied by fortitude, courage and perseverance.10 It is not up to him to create the warps and wefts, but to thread them harmoniously in a unity all the more firm and secure the wiser the conception of the fabric. It is this social fabric which makes up the People, the Nation, the Fatherland, and the State, and its basic pattern is the one resulting from family ties and from tradition. The finest and hardest of these warps is the sacrament of Matrimony where love, fidelity, perseverance, and concord come together in the deepest way.11

|

Marriage is the first bond of tradition which cements generation to generation, allows the flowering of moral values, teaches the value of work, and enforces the necessity of community and neighborhoods as a perfective force in human life.11 Aristotle conceives of the State as a self-sufficient union of families and municipalities,12 and understands the economy of the State to be based, not on the profit of the corporations measured by the stock market, but in the prudent administration of domestic communities.13 Indissolubility of the marriage bond is the cornerstone of any larger social group and is the essential factor in its stability and unity. If marriages and families can be broken then broken will be the People, the Nation, the Fatherland, and the State. In His mercy, Our Divine Lord Jesus Christ gave a sacramental character to the marriage union and made political and social peace among the faithful possible without the harsh enforcement of law hitherto necessary for example the "eye for an eye" mentality of the Persians. Thus, marriage and family bonds are as touchstones of true statesmen who, in the beautiful metaphor of Plato, will use the needle of the law, the customs of the people, of tradition, and of the exemplary order of love, to tie firmly this principal warp as the anchor of the social fabric.11

What are we to say of the politicians who have pushed us into a pit of social chaos where a family is no longer recognized as a political institution, where the very life of its members is threatened within its boundaries by abortion and domestic violence, where poverty and unemployment are disregarded in favor of financial profit and "global competitiveness" as if the global market were more important than domestic justice? They are like moths gnawing at the social fabric to feed on its spoils. They only care about the thickness of their wallet and the satisfaction of their gluttony, even if in the process of obtaining what they seek they have to destroy the very organism on which they feed. St. Thomas reminds us that the curse of God is upon them: "Thus saith the Lord God: Woe to the shepherds of Israel, that fed themselves because they seek only their own comfort]: should not the flocks be fed by the shepherds?"14

"For the wages of sin is death. But the grace of God, life everlasting, in Christ Jesus our Lord" (Rom. 6:23).

When discussing the issue of authority, St. Thomas Aquinas teaches that "man, who acts by intelligence, has a destiny to which all his life and activities are directed, for it is clearly the nature of intelligent beings to act with some end in view."15 Now, when any given unity is directed to an end, be it physical as our body or political as the State, "it can sometimes happen that such direction takes place either aright or wrongly. So political rule is sometimes just and sometimes unjust." It is just when it is ordered to its proper end and unjust when it is not. "[In the best State] the task of the lawgiver would be 1) to see that men become good; 2) to find the appropriate means by which this can be accomplished, and 3) to know what the end of the best life is" (Aristotle, Politics, 1333a, 14-17).

But, precisely what is the proper end of the political rule and of the State? St. Thomas answers, "If a community of free men is administered by the ruler for the common good, such government will be just and fitting to free men," and by contrast, "if, on the other hand, the community is administered in the particular interest of the ruler [or rulers, as he clarifies in a later paragraph], this is a perversion of government and no longer just." When the unjust rulers are few, as in the cases of oligarchy or its modern version, plutocracy, or many, as in the case of democracy, "the entire community becomes a sort of a tyrant."15

Thus, the political common good is the divider between just and unjust leadership, but then again, what is the common good, and who is to determine it? Is it not perhaps best identified by the will of the majority, the public opinion, or by the power of the rich and famous? The answer to these emotion-laced questions lies again in the first principles.

Particular interests, even those of a fickle majority which displays them on Election Day, divide the community, whereas the common good unifies it. But matters which differ thus must originate from different causes, and for this reason whenever there is an ordered unity arising out of a diversity of elements there is to be found some unifying and controlling influence.15 In the case of the State, the perfect community destined to provide all the necessities for the fullness of life and its defense, the unifying principle is given by the authority of the ruler,15 and in a Republic, by laws.16 St. Thomas Aquinas says: "It is those who obey the same laws, and are guided by a single government to the fullness of life, who can be said to constitute a social unity."17

Since the State exists to provide a perfect and self-sufficient life for its citizens, such a condition of life is its final cause, or end, and as we have seen it is by pursuing it that government achieves justice. Now, a perfect life is one which is lived according to virtue.19,20 Thus, the object of human society is a virtuous life.21 Now, "the man who lives virtuously is destined to a higher end,"22 namely, the enjoyment of God, and since the end of a human association can't be different from the end of the individual man, "the end of social life will be, not merely to live in virtue, but rather through virtuous life to attain the enjoyment of God."12

Therefore, the Law, strictly understood, has its first and principal object in the ordering of the common good, understood as such fullness of life as would allow citizens to lead a virtuous life and through it attain the enjoyment of eternal life.23

Catholic leadership is thus necessary for the achievement of common good. It is for this reason that those who by their virtuous life "contribute most to the life [of the Republic] are a greater part of the State than those who are equal or greater in freedom or birthright but inferior in virtue, or than those who exceed in wealth but are exceeded in virtue."24

Indeed, for a political leader, "nobility of high birth does not matter as much as the natural virtue that [he] may possess, because the latter is not something that can be gotten from ancestors, but is instead gained by deeds so remarkable as to be called noble, with nobility gained by virtue, strength, will and heart"25 performed to the greater glory of God and for the Fatherland.

1. St. Thomas Aquinas, De Regimine Principum, Book I, Chap. I.

2. Aristotle. Politics, 1331b, 27-ss.

3. Aristotle. Politics, 1332a, 34-37.

4. Feast of St. Ferdinand, King and Confessor, May 30. Daily Missal, Fr. J. P. de Urbel, Spain.

6. Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quixote de la Mancha, 1605.

7. Rafael Puddu, El Soldado Gentilhombre, (Barcelona, Spain, 1984).

8. St. Thomas Aquinas, De Regimine Principum, Book I, Chap. IX.

9. Aristotle, Politics, VII, 1325b, l0-15.

10. Plato, The Politician, 279a-ss.

11. F. A. Lamas, El Tejedor y la Polilla, Moenia, XXVIII, 1987.

12. Aristotle, Politics, III, 1280b-1281a.

13. Aristotle, Politics, I, 1256.

14. Ez. 34:2

15. St. Thomas Aquinas, De Regimine Principum, Book I, Chap. I.

16. Aristotle, Politics, 1282b, 2-7.

17. St. Thomas Aquinas, De Regimine Principum, Book I, Chap. XIV.

18. Aristotle, Politics, 1252a, l-5; 1280b, 40-1281a2.

19. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1098a, 16-18.

20. St. Thomas Aquinas, De Regimine Principum, Book I, Chap. XIV.

21. Aristotle, Politics, 1323b, 40-43.

22. St. Thomas Aquinas, De Regimine Principum, Book I, Chap. XIV.

23. St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I-Ia, Q. 90, 2-3.

24. Aristotle, Politics, 1281a, 4-8.

25. Rafael Puddu, El Soldado Gentilhombre (Barcelona, Spain, 1984).