Heresy Blossoms Like a Rose (Pt. 2)

Part 2

AMERICANISM, 1890-1900

Continued from the April 2000 issue of The Angelus, the conclusion of this article discovers more of the intrigue between the fearsome foursome: Ireland, Keane, O'Connell, and Gibbons. The effects of Leo XIII's Testem Benevolentiae in the United States. The ascent of Pope Pius X and the reaction of Americanists.

During the 1800's Protestants developed the idea that God wanted the United States to dominate the Western Hemisphere "from sea to shining sea." This notion was behind the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the Florida Purchase of 1819. In the 1840's "Manifest Destiny" meant that as Americans conquered the Southwest there would be more room for "the downtrodden of Europe." One defender of expansion denounced "the mixed Spanish, Indian, and Negro people of Cuba, Mexico, Central and South Americas, overwhelmingly Catholic, as "the worst portion of God's footstool." America should seize their lands since they were "devoid of the slightest spark of moral principle, devoted to the most debasing vices, destitute of industry or enterprise, [and] render worthless the territory upon which they have existence."1

The Protestant mentality articulating such thoughts clearly believed in a divinely-ordained superiority for Anglo-Saxons and a divinely-inflicted inferiority for non-Nordic Caucasians and people of color. Such thinking was clearly beyond the pale for Catholics unless they were Americanists.

|

James Cardinal Gibbons |

By the end of the 19th century "Manifest Destiny" came to mean imperialistic expansion overseas for reasons necessary (read, God wills it) and benevolent (read, uplift savages). Despite the manifest un-Catholicity of the concept, Protestant America had no more staunch defenders in seizing an overseas empire from Spain in 1898 than the Catholics in the United States about to be condemned as Americanists. Denis O'Connell and John Keane believed that if America trounced Spain the conservative, anti-Americanist Italian, French and Spanish Churchmen who manned the bureaucracy in Rome would be visibly weakened. If that happened, the way back to respectability for Americanists would be eased considerably. John Ireland, who supported efforts to lessen European influence in Rome, had the added incentive of pleasing a president who would use the diplomatic machinery of the United States government to further an American prelate's quest for a Red Hat.

A wary William McKinley successfully withstood the nearly criminal drumbeat of anti-Spanish hysteria whipped up by a jingoistic press throughout 1897. In March, 1898, after an American battleship exploded in Havana harbor, Archbishop Ireland joined the jingoes demanding war. During a visit to the White House he assured the President that the Catholic Church favored action to "free" Cuba. The pacifist-inclined McKinley finally relented, and in April he asked Congress to declare war "to liberate Cuba from Spanish oppression." The first battle in the Spanish-American War took place four weeks later when the American Asiatic Squadron captured the Spanish naval base at Manila, a Catholic city in the Philippine Islands, 10,000 miles from Cuba.

The conquest of the Philippines took the President by surprise: "When I first heard that Admiral [George] Dewey had captured those darn islands I couldn't tell within 2,000 miles where they were located." But the President was also practical. We had the islands. Both England and Germany seemed to want them, so they must be worth something. "I did not know what to do," said the President. "So I prayed, and then it came to me. We should take them, take them all, and liberate, uplift and Christianize the Filipinos as our fellow man for whom Christ also died."2 Although the people of the Philippines had been Roman Catholic since 1521 when priests with Ferdinand Magellan introduced them to the Faith, to a good Methodist like McKinley the natives still needed "Christianizing."

Two weeks after the Battle of Manila Bay, Denis O'Connell wrote from Rome to thank John Ireland for not stopping McKinley from going to war with Spain. The letter is important because it shows a prelate so consumed with hatred that he endorsed the use of force to raise humanity to a higher plane:

It is the question of all that is old & vile & mean & rotten & cruel & false in Europe against all [that] is free & noble & open & true & humane in America. When Spain is swept off the seas much of the meanness and narrowness of old Europe goes with it to be replaced by the freedom and openness of America. This is God's way of developing the world....At one time one nation in the world now another, took the lead, but now it seems to me that the old governments of Europe will lead no more and that neither Italy, nor Spain will ever furnish the principles of the civilization of the future. Now God passes the banner to the hands of America, to bear it [in] the cause of humanity....Hence I am a partisan of the Anglo-American alliance, together they are invincible and they will impose a new civilization [Emphasis added].3

It is instructive to compare the rhetoric of Catholic Bishop Denis O'Connell with the racist ravings of Indiana's Albert J. Beveridge in his maiden speech to the United States Senate in January, 1900. Beveridge embodied Imperialism and the Progressive Movement in America during the first quarter of the 20th century. As a Protestant, a Mason, a biographer of Chief Justice John Marshall and of President Abraham Lincoln, and as Theodore Roosevelt's vice-presidential running mate in 1912, Beveridge also embodied all that was considered best in American civilization. In pleading for the annexation of the Philippines, the gentleman from Indiana spoke in terms somewhat akin to "Master Race" rhetoric in Germany during World War II:

Mr. President, the times call for candor. The Philippines are ours forever: "territory belonging to the United States" as the Constitution calls them....We will not repudiate our duty in the archipelago....We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustees under God, of the civilization of the world. And we will move forward to our work, not howling out regrets like slaves whipped to their burdens, but with gratitude for a task worthy of our strength and thanksgiving to Almighty God, that He has marked us as his chosen people, henceforth to lead in the regeneration of the world....God has not been preparing the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-contemplation and self-admiration. No! He has made us the master organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns....He has made us adepts in government that we may administer government among savage and senile peoples... [Annex the islands to] begin our saving, regenerating...uplifting work.4

There can be no doubt that Catholic prelates were in bad company when they co-operated with Masons like William McKinley and Albert Beveridge to foster a war between Protestant America and Catholic Spain, a war that unexpectedly involved the Philippine Islands. There also can be no doubt that Catholic authorities in Rome were aware of another war that began in 1896 when Emiliano Aguinaldo, a 33rd degree Mason, led a revolt in the Philippines against Spanish rule and the Catholic Faith. Aguinaldo continued his war against the Church unimpeded after America annexed the islands in 1901. Theodore Roosevelt, who became President in 1901, Elihu Root, Secretary of State at the time, and William Howard Taft, first United States High Commissioner of the Philippines, were also Masons.5

Dennis Dougherty, the first American bishop in the Philippines, saw first hand what Aquinaldo's war portended. The prelate was "hardly prepared for the reality" he found on October 22, 1903, when he took formal possession of the Diocese of Nueva Segovia:

The cathedral was scarred by war and sadly in need of repairs, both outside and in. The bishop's house...had been entirely stripped of its furnishings, and the chapel had been used to stable a native general's horse. The large seminary was in a state of disrepair, despoiled of...furnishings, and the many books in its excellent library had been appropriated by native shops and stores as wrapping paper...

The Masonic war against the Church also "unleashed a spirit of rebellion among the native clergy." One of them, Fr. George Aglipay, "had gone into schism with large numbers of his followers, and had taken over a great many church lands and buildings." As a result, during his first year Bishop Dougherty had doors slammed in his face, and he was locked out of some of the half-ruined churches. He stayed the course for almost 13 years during which he restored the Church to vitality throughout the islands. In 1915 Dougherty returned to the United States where he became bishop of Buffalo and eventually Cardinal Archbishop of Philadelphia.6

Rome moved throughout the 1890's to curb what prudent Churchmen saw as Americanist excesses. In 1893 Propaganda expressly condemned several secret societies despite impassioned objections by Gibbons and Ireland. In 1894, following the scandal of the Chicago Parliament of Religions, Pope Leo XIII forbade further participation in inter-faith congresses. In 1895 he addressed Longinqua Oceani to the American bishops with its express reservations regarding religious liberty and separation of Church and State. Later that year Denis O'Connell was removed as rector of the North American College and in 1896 John Keane was removed as rector of the CUA. Any one of these steps alone, and certainly all of them collectively, should have warned Americanists to cease and desist. Instead, however, they redoubled their efforts.

From 1890 through 1898 John Ireland engaged repeatedly in partisan politics while seemingly heedless of adverse after-effects. He was always supported in his schemes by Gibbons in Baltimore, O'Connell in Rome, and Keane either in Washington or Rome. The actions of these four prelates against Catholic Spain in 1898 constituted spiritual betrayal in view of the dire consequences visited upon the faithful in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the Philippine Islands. The Spanish aspect of Americanist policy alone cried to Rome for reprimand.

|

|

|

Cardinal John Farley (left) and Cardinal William O'Connell (right)

who were appointed by Pope St. Pius X in 1911. |

|

The reprimand came when anti-republican Frenchmen accused Catholics in the United States of trying to Americanize Catholicism. A struggle over what the French called "Americanism" was precipitated in 1898 by the translation into their language of Walter Elliott's Life of Father Hecker. Conservative French clergymen found the hagiographical introduction by John Ireland especially offensive. Cardinal Gibbons objected when it became obvious that Leo XIII would intervene in the matter. Although it was too late to stop Leo entirely, he did temper his condemnation. Instead of naming names and citing chapter and verse of specific abuses, Leo proclaimed that he did not mean to condemn the American spirit per se, or even any doctrine that Americans necessarily accepted. Rather, said the Pope, he used the term Americanism because it was used in Europe to describe certain un-Catholic ideas.

This "soft" condemnation was contained in the apostolic letter Testem Benevolentiae, [see The Angelus, April 1987, pp. 10-13] addressed to James Cardinal Gibbons on January 22, 1899. After admitting affection for the people of the United States the Pope said he was obliged to warn them against certain matters that must be avoided or corrected. He then discussed five points of questionable doctrine: one, it was wrong to assert that in our days spiritual direction is less needed than in earlier times; two, natural virtues must not be extolled above the supernatural; three, it was wrong to divide virtues into passive and active categories and hold that the active are more suitable for our days; four, the vows taken in religious orders must not be regarded as narrowing the limits of true liberty, or as of little use for Christian perfection; and five, it is imprudent to neglect the methods of the past in proselytizing non-Catholics with a view to their conversion.

All of these errors, usually associated with the late Isaac Hecker and his Paulist order, were condemned as Americanism. Neither Hecker nor anyone who supported his ideas, however, was named by the Holy Father. The letter concluded with an ambiguous paragraph that lacked the certitude and clarity usually found in doctrinal statements. On one hand the Pope said he did not mean to condemn Americanism if that term designated qualities which reflect honor on the people of America, their commonwealths, and their laws and customs. On the other hand if the term signified the five propositions, they must be condemned:

For it [the latter signification] raises the suspicion that there are some among you who conceive of and desire a Church in America different from that which is in the rest of the world. One in the unity of doctrine as in the unity of government, such is the Catholic Church, and since God has established its center and foundation in the Chair of Peter, one which is rightly called Roman, for where Peter is there is the Church.7

Although Testem Benevolentiae avoided most specifics, the document had an immediate impact. James Gibbons addressed his response to Leo XIII on St. Patrick's Day, 1899: "This doctrine, which I deliberately call extravagant and absurd, this Americanism as it is called, has nothing in common with the views, aspirations, doctrine and conduct of Americans."8 Within a year the hierarchy of the United States denied unanimously ever harboring the kinds of thought the Pope seemed to condemn. Gibbons, Ireland, Keane, and O'Connell continued to murmur Americanist thoughts in private, but publicly each bowed before the papal pronouncement. Except for Gibbons, these leaders avoided public pronouncements of an Americanist nature for the rest of their lives.

In 1900 John Keane returned from his self-imposed exile to become Archbishop of Dubuque, Iowa. Leo XIII enclosed a personal note with Keane's letter of appointment, a note "which sternly admonished the archbishop to avoid in his new ministry the errors set out in Testem Benevolentiae." Keane's years in Iowa were plagued by ill health. He resigned his bishopric in 1912 after suffering what was called "a nervous breakdown." He remained mentally unstable during his last years and died in 1918 while a guest at John Ireland's seminary.9

In 1903 the American bishops, at the urging of Gibbons, Ireland, and Keane, named Denis O'Connell the third rector of the CUA. Pope Leo XIII approved the appointment in one of the last acts of his pontificate, and O'Connell thereby became the second Americanist rehabilitated with the approval of the pope who condemned Americanism. He served as rector for six years during which he liberalized the faculty while maintaining a discreet silence on Americanist questions. Archbishop O'Connell died in office in 1909.

From 1887 to 1911 James Gibbons was the only American Cardinal. This was surprising since the number of Catholics in the United States increased from 8,909,000 to 12,041,000 during the 1890's. The increase from immigration was about 1,225,000, with Italy, Poland, Eastern Europe, and Canada furnishing nearly 90% of the newcomers. During the same decade the number of priests increased to 11,897 and new dioceses dotted the West in Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Texas, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and California.10 In the midst of this growth John Ireland concluded that the country needed a second Cardinal for the trans-Mississippi West and he could think of no one more qualified for the honor than himself. Ireland's Americanist friends lobbied shamelessly on his behalf and Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt touted his virtues through the American embassy in Rome. But it proved for naught. Pope Leo XIII, who had conferred the Red Hat upon Gibbons, steadfastly refused to name a second American Cardinal. When Pius X, the anti-Modernist future saint, succeeded Leo XIII, Ireland abandoned all hope of ever wearing a Red Hat.

In 1911 Pius X selected Archbishops John Farley of New York and William O'Connell of Boston as the next American cardinals.11 When the Archbishop of St. Paul made his ad limina visit to Rome shortly before the consistory to elevate the two new Americans, his past proved a source of embarrassment. The rector of the North American College forbade the seminarians to attend the sermons of an "arch-Americanist." Ireland revealed a sense of resignation, writing to a friend in Paris:

The wise mariner sets his sail in accordance with the wind-currents of the moment....I am very busy with...my new cathedrals, now journeying fast toward completion. And then the wind-currents across the Atlantic are not just now too favorable.

Acting as a wise mariner John Ireland spent his later years fulfilling a last dream: Twin Cathedrals for the Twin Cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis. Probably no other bishop had ever dared build two cathedrals simultaneously. But then few bishops ever thought in terms as big as the Archbishop who celebrated the centenary of the American hierarchy in 1889 by stating "I love my age, ...its feats, ...its industries, and its discoveries." He added "there is abundant room for material comfort beneath the broad mantle of Christian love." Twin Cathedrals, built with the coerced contributions of a flock which idolized him, were quite in keeping with Ireland's image of how an American prelate should live. His most recent biographer concluded that Ireland "quite purposely made of himself a bourgeois gentleman" who "lived in simple comfort, traveled extensively, maintained a decent carriage and stable, bought the books he wanted to read, and, in short, enjoyed the benefits that accompany financial independence." In Ireland's mind "An archbishop, after all, was not an anchorite who swore a vow of poverty. An archbishop was by definition a leading citizen."

|

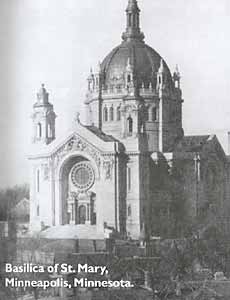

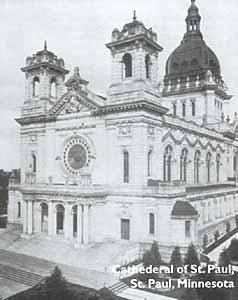

Bishop Ireland's Twin Cathedrals for the Twin Cities

|

|

|

|

Ireland's penchant for the good life was never better demonstrated than when James Gibbons toured the nation in 1887 to display his newly acquired regalia of a Cardinal. Gibbons traveled in a private car which James J. Hill furnished for the occasion. In St. Paul Ireland hosted a banquet at the city's "finest" hotel with civic and business leaders present. The speakers included United States Senator Cushman K. Davis, a Mason, who paid tribute to "America."

Ireland's Cathedral of St. Paul opened on Palm Sunday, 1915. A few months later the Basilica of St. Mary was dedicated in Minneapolis. These Twin Cathedrals for the Twin Cities were the Archbishop's last projects, and they constituted a fit tribute for a man who "took justifiable pride in crowning his career with an achievement doubters said could not be done."

John Ireland wanted his Cathedrals to remind subsequent generations of a Churchman who always promoted the best that America had to offer. Eighty years after his death, these twin legacies of the foremost Irish-American prelate of his day dominate Cathedral Square in downtown St. Paul and Basilica Square in downtown Minneapolis.

John Ireland died in his home across from his Cathedral on September 25, 1918. Upon hearing the news James Gibbons observed that now only he remained of the bishops who assembled for the Third Plenary Council in 1884. In a statement to the press the Cardinal described his late comrade as "the Venerable Patriarch of the West...who had endeared himself to the American people, without distinction of race or religion, the man who...more than any other...demonstrate[d] the harmony between the Constitution of the Church and the Constitution of the United States."13

Gibbons was correct in saying that John Ireland did more than anyone else to demonstrate that Catholicism and Americanism were compatible. But the Cardinal ran Ireland a close second and he stood almost alone in proclaiming Americanism publicly after Testem Benevolentiae. A statement in 1909 was typical:

American Catholics rejoice in our separation of Church and State, and I can conceive no combination of circumstances likely to arise which would make a union desirable....We know the blessings of our arrangement; it gives us liberty and binds together priests and people in a union better than Church and State. Other countries, other manners; we do not believe our system adapted to all conditions. We leave it to Church and State in other lands to solve their problems for their own best interests. For ourselves, we thank God that we live in America...where, to quote [Theodore] Roosevelt, "religion and liberty are natural allies."14

Anson Stokes and Leo Pfeffer, speaking as secular liberals in the United States during the second half of the 20th century, offered a non-Catholic evaluation of the Americanist heresy. "The general effect of [Testem Benevolentiae], with its condemnation of 'modernism' and 'Americanism,' was to retard substantially the adjustment of Roman Catholicism to democratic conditions, an effect which lasted until the ascension of John XXIII [1958]." Fortunately, they added, "one of the most vigorous and admirable leaders produced by the Roman Catholic Church in this country" appeared on the scene in the person of John Ireland to insure that Catholics did not become too retarded. More important than Ireland for Catholic development in a "favorable direction," however, was James Gibbons of Baltimore who did "more than any other person in the past hundred years to commend the Roman Catholic Church to the people of the United States, to interpret its views and adjust its work so as to make them effective under the conditions of religious liberty in our American democracy."15

Most Catholic writers have agreed with their secular counterparts that Americanism was a good thing. Those who have written with academic respectability since Vatican Council II generally see Americanists as harbingers of a new Church, men ahead of their time who paved the way to the glorious present. Earlier historians either ignored the heresy or downplayed its importance. Cardinal Gibbons, however, has been ever extolled. Theodore Maynard, writing in 1957, was typical:

The Catholic Church in America has produced several men who may have been abler than James Gibbons, and perhaps a few greater men, but there has never been one with just his combination of qualities—prudence, when it was called for, shrewdness of judgment, affability and benignity, ...resolute courage. He was for all Americans the outstanding Catholic of the age in which he lived.16

Francis B. Thornton displayed even more unreserved admiration. "Some revered him for his patriotism or his humanity," Thornton said, "some for his priestliness or wisdom. Few were able to see, as we can now, that the American Church as we know it today [1963] is largely his creation." Bear in mind that the Church Thornton describes as Gibbons's legacy is a Church on the brink of its post-1965 collapse:

That priests and people are one, that patriotism and religion go hand in hand, that prelates of any stature are capable of rising above their racial bias, that separation of Church and State assists the Church in "blossoming like a rose," that dialogue is possible and necessary between all who worship God, that understanding and love of the common people is the cornerstone of progress, all these [Gibbons] had fought for and built into the consciousness of the American Church.17

In summary, Americanist heretics made straight the way for today's apostate Church in the United States. When they and their Modernist confreres fell into disfavor, the heretics feigned somnolence while burrowing ever deeper into the marrow of the Church. Underground for 60 years, they surfaced after Vatican II and gained absolute control of the institutional Church in today's America.

Dr. Justin Walsh has an undergraduate degree in Journalism and a Master's degree in History from Marquette University and a doctorate in History from Indiana University. He currently teaches at the Society of Saint Pius X's St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary, Winona, MN, USA.

Footnotes

1. For "Manifest Destiny" prior to the Civil War, see Justin E. Walsh, To Print the News and Raise Hell: A Biography of Wilbur E. Storey (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968), pp. 36, 60-61.

2. McKinley as quoted by Professor Norman Graebner, "Realism Versus Idealism in American Foreign Policy," a paper read at Summer Institute on Recent American History, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, June, 1966.

3. Denis O'Connell to John Ireland, May 24, 1898, as printed in Thomas T. McAvoy, The Americanist Heresy in Roman Catholicism, 1895-1900 (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1963), pp. 163-165.

4. As printed in Claude G. Bowers, Beveridge and the Progressive Era (New York: The Literary Guild, 1932), pp. 119-122.

5. See "Masonry and the Philippine Insurrection" and "The American Connection with Philippine Masonry" in Paul A. Fisher, Behind the Lodge Door, Church: State and Freemasonry in America (Rockford, Illinois: TAN Books and Publishers, 1994), pp. 211-217.

6. "Dennis Cardinal Dougherty," in Francis B. Thornton, Our American Princes: The Story of the Seventeen American Cardinals (New York: G. Putnam's Sons, 1965), pp. 106-107.

7.See discussion and text of "Testem Benevolentiae" in Theodore Roemer, The Catholic Church in the United States (St. Louis: B. Herder Book Co., 1954), pp. 309-310.

8. As cited in John Tracy Ellis, American Catholicism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955), p. 119 and note 59, p. 175.

9. For Keane's last years, see Marvin O'Connell, John Ireland and the American Catholic Church (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988), pp. 477, 510-511.

10. For statistics see Roemer, The Catholic Church in the United States, p. 314.

11. For Ireland's pursuit of a Red Hat see O'Connell, John Ireland and the American Catholic Church, pp. 473-475, 492-498. Ironically, in 1895 William O'Connell had replaced Denis O'Connell as rector of the North American College. See Thornton, Our American Princes, pp.89-90.

12. O'Connell, John Ireland, "wise mariner," p. 506; "he lived in simple comfort," p. 378; banquet menu, p. 244, "justifiable pride," p. 514.

13. Ibid., p. 518

14. As quoted in Anson Phelps Stokes and Leo Pfeffer, Church and State in the United States (New York: Harper and Row, 1964), p. 322.

16. Theodore Maynard, Great Catholics in American History (New York: Hanover House, 1957), p. 208.

17. Thornton, Our American Princes, pp. 65-66.