A Politically Incorrect Monk

The Servant of God, Fr. Mark d' Aviano

|

In the Gazettino of Vienna last February 10th, the headline read: "He Made War on Islam: No Altars for Mark d'Aviano." Firstly, something needs to be made clear: It was not Mark d'Aviano that warred on Islam; rather, it was Islam that attacked (and not for the first time) Christendom on its eastern extremity: Austria, and Vienna in particular. The Capuchin Mark d'Aviano, son of an Italian land particularly martyrized by Islam, Friuli,1 did nothing more than uphold the courage of the Christian troops. And he did it in a Christian way, holy monk that he was, by urging the Viennese to do penance in order to stave off the scourge of Islam. To the Emperor Leopold I, who regarded him as a great saint and who, seeing the approach of the Muslim peril, had called upon his help, Fr. Mark, like a latter-day Jonas, answered him:

God is armed with scourges, because He has been provoked by our sins. It is fitting to appease Him by humiliations, repentance, and self-denial; and when our hearts have turned back to God, and when, in reparation for the public offenses that are committed against Him, we shall have rendered to Him the public homage which is due, I am certain that God, though He send affliction, will not will our desolation.2

Then he addressed a stern warning to the Viennese:

"Vienna, Vienna, your love of lax living has prepared you a grave and imminent chastisement: Convert, and consider well what you are doing, O wretched Vienna."3

He was heeded: the emperor commanded public penances, and the Viennese, like latter-day Ninevites, prayed and did penance.

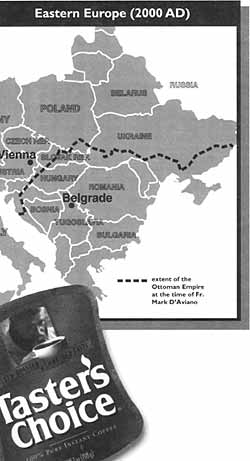

The Turks, against whom Pope Blessed Innocent XI had tried in vain to warn the Catholic kings and princes, were at this time heading towards Belgrade, where the sultan, who had been accompanied by his entire harem, halted and sent against Vienna, with the green banner of the "prophet," the great vizier Kara Mustafa.

The Muslim army advanced, massacring with utmost cruelty the garrisons and civilians, burning and pillaging with utmost greed, and besieged Vienna on all sides.4 The army was insufficient for the defense of the city, and all tradesmen, artisans, students and even domestics of the imperial court were summoned to battle: the city had to be held until outside help could arrive. It was an arduous undertaking, because, with the summer heat, an epidemic of dysentery broke out, killing 60 people a day. Every night, from the clock of St. Stephen's Cathedral, flares were set off to signal the relief troops of the extreme peril in which the unfortunate city was placed.

Meanwhile rescue armies had assembled in Bavaria, Saxony and Poland under the aegis of the Duke of Lorraine to march on Vienna and lift the siege. It was at this moment that Fr. Mark d'Aviano arrived, sent by Blessed Innocent XI. Emperor Leopold, who had had to flee from Vienna in order to escape falling into the hands of the Mohammedans, named him as his representative to the leaders of the relief army, leaders among whom it was necessary to constantly maintain peace in order to bring the enterprise to a successful conclusion.

As the emperor's representative, Fr. Marc d'Aviano participated in the war councils, and revealed himself to be a great military strategist. In fact his battle plan was very simple and supernatural: It was first necessary to repent of the offenses given to God and implore His mercy and help; then launch a mass surprise attack against the Mohammedans gathered around Vienna.

"The Turk will be vanquished and will leave us all his bags and baggage" he prophesied. And so it came to pass.

On September 12, 1683, Fr. Mark celebrated holy Mass, preached a brief, inflamed homily, publicly invoked God's help, and blessed the army. Thus commenced, in a Christian way, the battle that was to decide the fate, not only of Vienna, but also of the whole of Christian Europe.

The Christian army was heavily outnumbered by the Muslims, but Fr. Mark, crucifix in hand, without fear of danger, galloped from one front to the other to encourage the combatants, exhorting them to have confidence in God. When the Turks attacked, he would raise the crucifix against them, and cry: "Behold the cross of the Lord! begone, enemy troops." At the most critical, decisive moment a white dove appeared on the head of Fr. Mark, and hovered around him. For the Christians, who had invoked the help of the Madonna, and who fought, like Prince Eugene of Savoy, "in the name of Mary," it was the signal of victory, and they redoubled their courage. At the end of the day the Muslim army fled, abandoning in its camps a very rich booty, among which were 600 Christian children who had been made prisoner to send them to the sultan as slaves, and ten thousand sacks of coffee.

In the Cathedral of St. Stephen, the Te Deum was sung and everyone wept for joy. It was to commemorate this victory which saved Christian Europe that the Feast of the Holy Name of Mary was ordered to be celebrated on September 12th, a feast which, in our day, was ecumenically excised from the calendar by Paul VI, the same Paul VI who returned to the Muslims the green banner of Mohammed, wrested from the Grand Vizier by the Christians during the Battle of Vienna.

For 18 years Fr. Mark continued to encourage the Christian army in its struggle against Islam.

After Vienna, Hungary had to be delivered. Fr. Mark, as always, called for prayer, conversion, penance, and confidence in God. "It is not the poor troops of the Christian army that can rout the Turks, but rather the invincible aid of God. It is faith that must conquer, not arms."5

Nevertheless, with a holy realism, Fr. Mark worked, as the preceding popes had, to establish a "Holy League" among Christian princes for the deliverance of Christendom from the Turkish threat. To the Austrian emperor, who had been solicited to make peace with the Turks, he answered: "God desires war and not peace. Let us first deliver the Christian territories, then we can negotiate."6 And God visibly assisted Fr. Mark and accredited his words and deeds by innumerable prophecies and miracles. (Even the Muslims feared him as a "powerful magician"; and they wanted to know who was the "Lady" dressed in white whom they often saw at his side on the ramparts of Vienna). The Pope appointed him "Apostolic Missionary."

After the Battle of Vienna came the Battle of Buda. The city was in the hands of the Muslims, who had surrounded it by a triple ring of fortifications and had even transformed the city's cathedral, dedicated to St. Stephen, into a mosque. This time Fr. Mark held a banner of a very beautiful image of St. Joseph; throughout the battle he ran where the danger was greatest. As soon as a breach had been opened in the city walls, his thought turned to the profaned cathedral. Under the thundering canons he headed there, singing the litanies of the Blessed Virgin. By evening he was able to place his standard in the reconquered church.

In the unfortunate land of Hungary the Catholic religion had practically been effaced by the Muslims, but after the victory of Buda, the churches were rebuilt, and for Hungary, once again Catholic, began a period of splendor.

The deliverance of Essech came next. It had also fallen into the hands of the Muslims: "Have confidence, and the victory will infallibly be yours," Fr. Mark said to the generals of the Christian army, who, discouraged, were on the brink of ordering a retreat. Once again, the victory was theirs. Fr. Mark left the generals this advice:

In order to make a good war against a great enemy of the name of Christian, like the Turk, and in order to obtain success, above all things it is necessary, to have recourse with confidence to the God of hosts, without whom all human enterprise is vain.7

But with his healthy realism, which is the mark of saints, he did not neglect human industry and gave invaluable suggestions on training troops, on munitions and logistics, on marching and on spying, and, especially, on maintaining a good rapport among the leaders, who "must fight with upright intentions and not out of jealousy, pride, or personal interest."8

Then it was Belgrade's turn. The Austrian generals hesitated. "God absolutely wants this expedition," insisted Fr. Mark,9 and the Turks, who had a 99 percent chance of winning, took flight, leaving the Christians stupefied by the victory obtained despite the cowardice and indecision of their commanders.

When another terrible siege of Vienna appeared inevitable, Fr. Mark told the emperor: "Your Majesty's army can do nothing against the Turk, but if the Madonna is worthily honored, she will give the victory,"10 and he asked for solemn acts of public reparation. The penitential ceremonies had not yet been achieved when another astonishing victory was announced. "Fr. Mark all by himself has done more than all the others," the Viennese exulted, but Fr. Mark reprimanded them, telling them that Christians not only must pray to God and the Madonna when in danger, but that they must lead a life worthy of their baptism.11

In 1699 the Muslims, defeated, signed the Peace of Carlowitz. That same year saw the passing away of Fr. Mark, the holy Capuchin who played for Catholic Europe the same role that St. Joan of Arc had played for France.

|

I1 Gazzettino reminds us that the grateful Viennese dedicated to Fr. Mark d'Aviano the "capuziner," that is, "cappuccino," the beverage obtained by mixing milk in the Turkish coffee found in the enemy camp after the Battle of Vienna, and they invented a cake in the form of a half-circle, the Italian "cornetto" "in memory of this great victory which was above all religious." |

|

Three Hundred Years Later

The Viennese have not forgotten their savior, and their diocese, having introduced the cause of his beatification, had expected that during the next visit of the pope to Vienna he would announce the beatification of Fr. Mark d'Aviano, already declared "venerable" by St. Pius X. They received a cold shower: the Archbishop of Vienna, His Excellency Msgr. Schoenborn, announced that the cause had been set aside and that the expected beatification would not take place. "The decision," explained the Archbishop of Vienna, "was taken after opposition manifested [harken well!] by non-Catholic groups [later on he specifies the "Evangelical Church"] to the exaltation of a monk who had an evident role in the liberation of Vienna (1683) besieged by the troops of the Ottoman emperor."

And since when, we cannot help but ask, have "non-Catholics" had their say-so in the beatifications of the Catholic Church. And since when has the Church, in her beatifications, taken into consideration the erroneous canons of the "non-Catholics." And, finally, what have the members of the Evangelical Church (Lutherans) to do with Islam?

The fact is that, if the Viennese have not forgotten their savior, the Protestants haven't forgotten Fr. Mark d'Aviano either, for he was an indefatigable convertor. There were even Lutherans who tried to kill him. A few examples will serve. At Ratisbonne, the Protestant authorities closed the gates of the city to Fr. Mark, but they were obliged to allow him to enter by order of the emperor. Then they forbade him to preach, but the people protested. Finally, they erected a stage facing Fr. Mark and parodied him. However, the stage of the mockers suddenly collapsed, and it was their turn to be mocked by the crowd.

The same scenes were repeated at Augusta, a citadel of Lutheranism. There they also let Fr. Mark preach only after the crowd had protested that they wanted to hear him. Despite the "excommunication" with which the authorities threatened them, the Protestants swarmed to hear him, and were converted by the hundreds.

Thanks to Fr. Mark even some Protestant princes were converted, as well as a Calvinist "bishop" and the Baron Trienscenset, master general of the place. Yet Fr. Mark did not "dialogue" with the "separated brethren." He demanded their conversion of heart and abjuration of heresy, and the Protestants flocked to him, attracted by his reputation for holiness and by the miracles that seemed to spring from his hands, and many truly converted. The others covered him with insults and calumnies, composing outrageous lyrics that they had children sing, in which they called him a "Judas" and even "antichrist."12 At Roermont, the Protestants removed the underpinnings of the preacher's platform. When Fr. Mark went on stage together with all the authorities, the platform collapsed, but everyone escaped unharmed, and at the trial the holy Capuchin forgave the guilty, and obtained the return of numerous Protestants to the Catholic Church.

Hatred is as tenacious as love, and if the love of the Viennese desires that Fr. Mark be elevated to the honor of the altars, the hatred of the "evangelists" opposes it. And up to this point there is nothing unusual in this.

What is strange, though, is that the love of the Viennese receives no sympathetic hearing from the Catholic hierarchy, but, on the contrary, it is to the hatred of the Protestants that this same hierarchy lends its ear. Mark it as a sign of the times, times of ecumenical delirium in which we live.

But if Fr. Mark does not deserve the honor of the altars because he was wrong to defend the Faith and Christian civilization against the Muslim aggression, then it should be necessary to remove from the altars St. Pius V because of the Battle of Lepanto, of which the Battle of Vienna was the equivalent on land. It would be necessary to call into question the beatification of Innocent XI, who from Rome guided, encouraged, and authorized Fr. Mark d'Aviano; it would be necessary to go higher still, and call into question the cause of the Blessed Virgin, who visibly assisted Fr. Mark in the battle of Vienna, and finally it would be necessary to ascend to the throne of God Himself to demand of Him the reason for the incessant miracles by which He accredited Fr. Mark before his contemporaries. But, of course, logic is not the strong suit of modernists, and, in general, of the enemies of God.

One Austrian historian wrote against the beatification of Fr. Mark d'Aviano, that he would become "the saint of a militant Christianity." And that, let us add, is not appreciated by the modernists and their Protestant "separated brethren," who want nothing to do with a militant Christianity—the real one, which is identified with the Catholic Church; instead they want a conciliating Christianity, all the better to demolish it from within and without.

As for Fr. Mark d'Aviano, since no one can wrest from him the beatific vision of God, we think that he appreciates not being beatified by the modernists who are in the process of destroying what yet remains of the Christian West saved by him, above all by the supernatural arms of prayer and penance.

Marcus

(Translated from the Courrier de Rome, June 1998)

Footnotes

1. In the Battle of Lepanto it was not by chance that the best armed ship was the Friulians', and that the Friulians distinguished themselves by their bravery. See Marcello Bellino, Padre Marco d'Aviano (Udine: ed. Segno, 1991), p. 16.

2. M. Bellino, op. cit., p. 65.

3. Ibid., p. 66.

4. L. Pastor, Storia dei Papi [The History of the Popes], Vol. XIV/2, pp. 124ff.

5. M. Bellino, op. cit., p. 93.

6. Ibid., p. 89.

7. Ibid., p. 100.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., p. 102.

10. Ibid., p. 111.

11. Ibid., p. 112.

12. Ibid., p. 63.

13. L. Pastor, Storia dei Papi, p. 126.