Roman Catholicism & American Utopianism, Pt. 2

Part 2

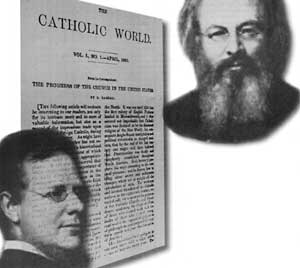

The Divergent Paths of Orestes A. Brownson and Isaac T. Hecker

Dr. Justin Walsh

|

|

Orestes Brownson's writings passed through three distinct phases after his conversion. During the first (1844-1855) he tempered his pessimism regarding democracy and claimed Americans had sufficient good will to join the Church if given the chance. Although the odds against a mass conversion seemed overwhelming in light of the Nativist movement during these years, Brownson seemed confident it would occur. Then, he predicted, the world would witness the most glorious days of the United States as it became a Catholic nation.

The second phase (1855-1865) began when Hecker, by then a priest, persuaded Brownson to move to New York and modify his "rigid dogmatism." Hecker sought Brownson's help with The Catholic World, a monthly magazine published by Hecker's Paulist order. Under Hecker's prodding, both the monthly and Brownson's Quarterly Review adopted a liberal theological tone. Brownson also revised his political thought in light of the Civil War. The result was a book in 1865 entitled The American Republic, a collection of wartime essays from his Quarterly. The pieces conveyed a vision of a United States with a providential mission and marked the one time after his conversion when Brownson nearly relapsed into a sort of Hegelian Utopianism:

"The United States...has a mission, and is chosen of God for the realization of a great idea. It has been chosen not only to continue the work assigned to Greece and Rome, but to accomplish a greater work than was assigned to either...to bring out in its life the dialectic union of authority and liberty, of the natural rights of man and those of society....The American form [of government]...is original, a new contribution to political science, and seeks to attain the end of all wise and just government by means unknown or forbidden to the ancients, and which have been but imperfectly comprehended by American political writers themselves."1

The third phase of Brownson's Catholic writings lasted from the end of the Civil War until his death in April, 1876. He folded his Quarterly in 1864 when the readership dropped because of the magazine's liberal editorial slant. From 1865 through 1872 Brownson supported himself and his family by writing for Hecker's Paulist periodical and also for The Ave Maria, a new Catholic magazine established by Fr. Edward Sorin at the University of Notre Dame. This last was a journal of orthodox Catholic conservatism and Brownson's first contribution was a set of beautifully written and touching essays on the Catholic practice of venerating saints and the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Brownson entitled the series "Saint Worship" and he began by tracing the word worship back to the Anglo-Saxon weorthscipe which meant simply the state or condition of being worthy of honor, or respect, or dignity. "The word may with like propriety designate the religious homage one owes to God, the reverence we give to the saints, or the civil respect we pay to persons in authority, whether in Church or State," he argued. He added that idolatry "is not in rendering worship to men, but in rendering to them the worship that is due to God alone." Brownson said Protestants overlook this and conclude "rashly" that Catholics are idolators. Since Protestants deny the sacrificial nature of the Mass, this attitude:

...is not strange or surprising. Having rejected the sacrifice of the Mass, they have no sacrifice to offer, and therefore really no supreme, distinctive worship of God; and their [highest] worship is of the same kind, and very little, if any, higher than that which we offer to the saints...[since they believe that] Christ's sacrifice was completed, finished in the past, and is not an offering continuously made, their churches have a table, but no altar except by a figure of speech, as it is only by a figure of speech that they commune of the body of our Lord...

Brownson concluded his introductory essay by asserting that the Catholic Mass really and truly was the supreme and distinctive worship of God. "As we have the true spiritual worship and offer it only to God, we can accept and encourage the overflowings of the pious heart towards the saints without any danger of idolatry."2

During these Ave Maria years matters came to a head between Brownson and Hecker. From 1868 to 1872 the editor and priest were embroiled in nearly constant disputes regarding such things as the effects of original sin. The priest "was consistent in his moderately liberal outlook, the layman grew more rigidly conservative." Brownson denounced "latitudinarian Catholicity" and said the faithful, "led by the Pope," must confront the evils of modern civilization head-on. To Hecker's chagrin Brownson used his Catholic World forum to denounce such 19th-century panaceas as atheistic materialism, spiritualism, and the women's suffrage movement. With respect to the last he wrote in 1869, "I look upon the present movement as the most dangerous that has ever been attempted in our country."

The final break came in 1870 when Hecker requested Brownson to write an article on separation of Church and State in the United States. The priest suggested a piece along the following line of thought:

In our country, where the church exists in her entire independence from State control, yet all her rights acknowledged and protected by the laws of the country, where her right to hold property, of establishing colleges, schools, charitable associations, etc. and to govern and administer her affairs according to her own laws and customs; it is here she is putting forth an energy and making conquests which vie with the zeal and success of the early ages of Christianity.

Brownson's essay on "Church and State," arguing that separation was an anti-Catholic principle, was not what Hecker had in mind. The degree of difference on what the Catholic Faith taught was spelled out by Brownson in a letter to his son, Henry:

The only trouble...grows out of the fact that Father...is not sound on the question of original sin, and does not believe that it is necessary to be in communion with the Church in order to be saved. He holds that Protestants may be saved by invincible ignorance, and that original sin was no sin at all except the individual sin of Adam, and that our nature was not wounded...by it. Father Hecker...is in fact a semi-pelagian without knowing it.3

When Ulysses S. Grant was re-elected in 1872 despite burgeoning scandals throughout his administration, Orestes Brownson abandoned any illusions he might have harbored about the natural goodness of the American people. They had lost a grip on the ideals of the republic, he said. The country was heading to its doom, society was degenerating through democratism, industrialism, and the corruption of morals. In that same year Fr. Sorin invited Brownson to retire at the University of Notre Dame. But Brownson refused because he was determined to revive his Quarterly Review. In January, 1873, he began to publish a "Last Series" in the first of which the editor disclaimed ever having been a liberal Catholic. His denunciation of Catholic liberalism was so scathing, and so filled with the wisdom of integral Catholicism, it must be quoted at length:

I must confess, to my shame and deep sorrow, that for four or five years, ending in 1864, I listened with too much respect to these liberal and liberalizing Catholics...and sought to encourage their tendency as far as I could without absolutely departing from Catholic faith and morals.

I had been taught better, and my better judgment and my Catholic instincts never went with them; but I was induced to think that I might find in the more fondly cherished tendencies of my non-Catholic countrymen, a point d'appui for my arguments in favor of the teaching of the Church, and by making the distance between them and us as short as possible, greatly facilitate their conversion. My faith was firm and my confidence in the Church unbroken, but I yielded to what seemed at the moment a wise and desirable policy.

All I gained was the distrust of a large portion of the Catholic public and a suspicion among non-Catholics that I was losing my confidence in Catholicity and was on the point of turning back to some form of Protestantism or infidelity. But I was not long, through the grace of God, in discovering that the tendency I was encouraging would, if followed to the end, lead me out of the Church, and as soon as that became clear to me I did not hesitate to abandon it and bear as well the humiliation of having yielded to any un-Catholic and dangerous influence. [Emphasis in original.]4

In October, 1875, the 72-year-old warrior-writer published the last issue of Brownson's Quarterly Review and moved to Detroit to live with his son, Henry. He died in that city on April 17, 1876. Ten years later his remains were transferred to a permanent vault in the Sacred Heart Church on the campus of the University of Notre Dame. Much of what he wrote after his conversion was more genuinely Roman Catholic than most writings that come from American Catholic pens. In fact, his writings contained sufficiently correct insight to make Orestes Brownson that rarest type of American Catholic, a genuine hero of integral Catholicism.

Isaac Hecker entered the Catholic Church in 1844 as a self-styled mystic well-schooled in Utopian Socialism and civic Americanism. As with many such mystics, the 25-year-old believed himself in possession of a special charism that flowed from a direct indwelling of the Holy Spirit. At the same time, however, Hecker was unschooled in Christianity, including Roman Catholicism. By his own admission a pious Methodist mother had arranged no formal religious training for Isaac as a child. As a teenager he attended lectures by nearly agnostic Unitarian ministers and substituted Transcendentalist meditation for theological inquiry. When initially rebuffed in 1844 because he lacked sufficient understanding of the Faith, Hecker sought and found a sympathetic prelate who baptized the catechumen after only one month of catechesis. Then, again by Hecker's own admission, not even four years of study for the priesthood remedied this deficiency: "I never went to class those years (in seminary). I was a kind of scandal, of course, in the house....I hadn't a book in my room." As one biographer commented, a complete absence of theological studies can be a great and irreparable void in the life of a priest.5

This void never bothered Hecker because he felt himself under a special dispensation with no need to know dogmatic theology. As he wrote from Holland while studying for the priesthood in 1848: "I believe that Providence calls me...to America to convert a certain class of persons amongst whom I found myself before my conversion." He referred, of course, to his friends at Brook Farm. He asked on the eve of his conversion if "the doctrine of unity and diversity of action...held by these men...is [not] Catholicity in the industrial world?" Just four months before entering the Church Isaac Hecker thought that Utopian Socialism might be no more than Roman Catholicism adapted to the industrial world. Only a mystic who wrote as follows could labor under such presumption: "...it was God's will to set apart some men for a certain work and specially prepare them for it, and cause them, as He had me, to be brought under the influence of special Divine graces from boyhood."6

Whereas Orestes Brownson was led to the Faith by philosophical arguments and intellectual conviction, Hecker's conversion was motivated mainly by his belief that only in the Catholic religion could his mystical longings be satisfied. Their divergent paths to Rome colored everything they subsequently did as Catholics. While Brownson became a stalwart champion of orthodoxy, Hecker set out on a 45-year safari in search of the irreconcilable, i.e., a sort of mystical synthesis of civic Americanism tinged with a kind of Catholic Utopianism.

Hecker's long-standing desire to serve God by evangelizing American non-Catholics led him to the novitiate in Holland of the missionary Redemptorist order in 1845. Dispensed from the normal schedule for studies by his superiors, he took preliminary vows in 1846 and was ordained a priest in the autumn of 1849. He returned home in 1850 with four fellow priests who, like himself, were American converts. Their plan was to proselytize as Americans among American Protestants and unbelievers. Trouble arose in 1855 when Hecker and his friends challenged their superiors about "Old World" methods of proselytizing. The upshot of the affair was that Hecker and his four companions were charged with breaking their vows of obedience and expelled from the Redemptorists in 1857.

Fr. Hecker appealed the expulsions directly to the Holy See, where he demanded and received an audience with Pope Pius IX. According to Hecker's account, when the Pope entered the room the appellant fell on his knees and said "Look at me, Holy Father; see, my shoulders are broad. Lay on the stripes. I will bear them. All I want is justice. I want you to judge my case. I will submit."7 These theatrics worked. In March, 1858, Pope Pius IX formally released Hecker and his four colleagues from the Redemptorist order and encouraged them to form a new community to fulfill their dream of using "American methods" to convert American non-Catholics. Thus in 1859 the Congregation of St. Paul the Apostle, or "Paulists," was founded in New York under Archbishop John Hughes.

Fr. Hecker remained the new order's Superior General for the rest of his life. In addition to guiding the mission work, he started such magazines as The Catholic World: A Monthly Eclectic Magazine of General Literature and Science in 1865, and in 1870 The Young Catholic, an illustrated magazine for children, and he authored several books.

In the fall of 1869 Pope Pius IX convened Vatican Council I, the first general council of the Church in which Americans would take part. Fr. Hecker, eager to attend a gathering that he perceived would "inaugurate a new era in history," won appointment as a procurator for the non-attending Bishop Martin J. Spalding of Baltimore. Hecker arrived in Rome in November. While en route he learned of a group organizing opposition to the definition of papal infallibility and he immediately associated with this faction. The Paulist superior who remained silent in 1864 in the face of Pope Pius IX's "misbegotten" Syllabus, was adamant during Council deliberations that a definition of infallibility was inopportune at best and fatal for evangelization. He remained a staunch anti-infallibilist even after the Council decreed the doctrine. When the Franco-Prussian War forced the Council to adjourn suddenly in the spring of 1870, Hecker came home declaring:

I return with new hope and fresher energy, for that better future for the Church and for humanity which is in store for both in the United States. This is the conviction of all intelligent and hopeful minds in Europe. They look to the other side of the Atlantic not only with great interest, but to catch the light which will solve the problems of Europe....I return to my country a better Catholic and more American than ever. [Emphasis in original.]8

Hecker's most important book was The Church and the Age: An Exposition of the Catholic Church in View of the Needs and Aspirations of the Present Age. The book is important because it graphically illustrates the priest's Utopian determination to synthesize civic Americanism and Roman Catholicism for the good of all mankind. The work was published by the Paulist Press in 1887, just a year before Hecker's death. In it he went to extraordinary lengths to prove that the Syllabus of Errors did not apply to the United States because its government was the best possible for Catholics. He declared it was a noble act for early Catholic colonists "to proclaim that within the province and jurisdiction of Maryland no Christian man should be molested in worshipping God according to the dictates of his conscience, and whoever supposes that the Syllabus teaches anything to the contrary seriously mistakes its meaning." The Catholics of Maryland should also be thanked for separation of Church and State not only in the United States but everywhere:

Let then those Catholic Anglo-Americans have their due share of praise for the religious toleration of which they were the first to give an example—an example, furthermore, which had a formative influence in shaping the republic and its free institutions. For the principle of the incompetency of the State to enact laws controlling matters purely religious is the keystone of the arch of American liberties, and Catholics of all climes can point to it with special delight.

As for combining civic Americanism with the Faith, Hecker proclaimed without hesitation that:

The form of government of the United States is preferable to Catholics above other forms. It is more favorable than others to the practice of those virtues which are the necessary conditions of the development of the religious life of man. This government leaves men a larger margin for liberty of action, and hence for co-operation with the guidance of the Holy Spirit, than any other government under the sun. With these popular institutions men enjoy greater liberty in working out their true destiny. The Catholic Church will, therefore, flourish all the more in this republican country in proportion as her representatives keep, in their civil life, to the lines of their republicanism. [Emphasis in original.]9

The Catholic Church Progress in St. Louis had a different but more accurate view of the United States government when it commented on Hecker's book. The newspaper observed that marriage laws in this country were based on Protestant doctrine and the public schools were conducted in the interests of Protestantism. Also, the cornerstones of most public buildings were laid under the auspices of Freemasonry; nearly all chaplains utilized for government ceremonies were Protestant ministers; and state charitable and penal institutions were nearly all directed by Protestant bodies. And yet there were Catholics like Fr. Hecker who professed to believe that Catholicism was thriving under America's equal rights. "The truth is," concluded the St. Louis paper, "there is not a Catholic country in the whole world which does not show more consideration for the conscience of its non-Catholic population, however small this may be, than the United States shows for the conscience of Catholics in this country."10

According to his Paulist confreres, Superior General Isaac Hecker rarely said Mass or received the Eucharist during the last three or four years of his life. During these years he suffered a good deal from depression, what he himself called "almost unceasing desolation" and "awful darkness of soul." These years of relative inactivity were very hard for an active man like Hecker to endure. "Without the Book of Job" he said, "I would have broken down completely." On the night of December 20, 1888, two days after his 69th birthday, Isaac Hecker gave his summoned community a blessing in a feeble whisper, sank into unconsciousness, and died.11

Biographers offer disparate views regarding Hecker and his place in American Catholic history. Fellow Paulist Walter Elliott in closing his Life of Fr. Hecker in 1891 wrote, "We do not bid him farewell, for this age and especially this nation, will hail him and his teachings with greater and greater acclaim as time goes on." Fr. Elliott added, "As God guides His Church...into fullness of Catholic truth and virtue, Isaac Hecker will be found to have taught the principles and given the methods which will lead most surely to success." Fr. Charles Maignen, a French priest writing in 1898 against the Americanist heresy, saw Hecker differently: "This subjectivist crank has sown in his writings...the germ of all the ideas which a group of American prelates, with a hardihood and tenacity truly amazing, are now endeavoring to establish in the Church." An anonymous Paulist writing in the Catholic Encyclopedia in 1913, a decade after the Americanist crisis, struck a defensive note:

It is quite generally recognized by American Catholics that among the notable champions of the Holy See in the 19th century, none was more loyal, none spent himself more generously, than Isaac Hecker. The hierarchy in the United States all but unanimously gave spontaneous testimony that Fr. Hecker had never countenanced any deviation from, or minimizing of, Catholic doctrines.

In 1964 two non-Catholic specialists in questions of Church and State hailed three "liberal-minded" Catholics from the second half of the 19th century as "men who deserve respect. They were Isaac Thomas Hecker, Archbishop Ireland, and Cardinal Gibbons." Hecker especially "was an ardent American, deeply interested in democracy and anxious to adjust the Church to American conditions." Paulist Fr. David J. O'Brien, Hecker's most recent biographer, said in 1992 that the Paulist founder made a major contribution to the way in which Catholic Americans approached their Faith. He was, said O'Brien, "a man ahead of his time" in the Church, a priest with "foresight" who anticipated the "spirit of Vatican II" by a century.12

These contradictory evaluations raise antithetical questions. Should Isaac Hecker be remembered primarily as a prominent 19th-century Roman Catholic American who was a friend of Orestes Brownson? Or was Hecker something quite different, an American Catholic Utopian priest who helped pave the way in the 19th century for the late-20th-century American Church? The historical record suggests he was the latter.

Dr. Justin Walsh has an undergraduate degree in Journalism and a Master's degree in History from Marquette University and a doctorate in History from Indiana University. He spent 18 years as a university professor before resigning from teaching because of the deterioration of university standards in morals and academics. He currently teaches at the Society of Saint Pius X's St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary, Winona, Minnesota, U.S.A.

Footnotes

1. Orestes A. Brownson, The American Republic, as cited in ibid., p. 35.

2. Orestes A. Brownson, Saint-Worship [and] The Worship of Mary (Paterson, New Jersey: St. Anthony Guild Press, 1963), edited and abridged by Thomas R. Ryan, C.PP.S., Essay I, pp. 3-7.

3. For the final divergence between Brownson and Hecker see Gower and Leliaert, Correspondence, Introduction, pp. 38-42.

4. Brownson's Quarterly Review (1870), as quoted in Maignen, Father Hecker, pp. 387-389.

5. Maignen, Father Hecker, p. 27.

6. Gower and Leliaert, Correspondence, Call of Providence, p. 20; Catholicity in industrial world in Isaac Hecker to Orestes Brownson, April 6, 1844, in ibid., p. 91; special Divine graces as quoted in Maignen, p. 9.

7. As recounted in Maignen, Father Hecker, p. 66.

8. Hecker to Father Walter Elliott, as quoted in ibid., p. 296.

9. I. T. Hecker, The Church and the Age: An Exposition of the Catholic Church in View of the Needs and Aspirations of the Present Age (New York: The Catholic World, 1887), pp. 66-67, and pp. 106-107.

10. St. Louis Church Progress, as quoted in Maignen, Father Hecker, pp. 192-193.

11. For Hecker's last years and death, see Maynard, Great Catholics, p. 190.

12. Elliott, Father Hecker, p. 366; Maignen, Father Hecker, p. 220; "Isaac Hecker," in Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), Vol. 7, p. 187; Anson Phelps Stokes and Leo Pfeffer, Church and State in the United States (New York: Harper and Row, 1964), pp. 319-320; and O'Brien, Isaac Hecker, pp.l-13.