Holy Hour: A Hidden God

Msgr. Ronald Knox

Isaias says (xl.15), "Truly thou art a God of hidden ways." I want you to consider how God hides Himself in four connections; in His creation, in His dealings with men, in His Incarnation, and finally in the Holy Eucharist. And I want you to see the four attitudes which that challenge is meant to evoke from us; our faith, our confidence, our humility, and finally our resignation.

|

God hides Himself in His creation; or rather, He reveals Himself in His creation, but in such a way that it is possible not to see Him. He does not deceive us, but He allows us to deceive ourselves. We all know the five proofs which philosophy gives us of the existence of God, and we all know that those proofs are cogent, even if we had no other light, the light of conscience for example, to illustrate them further. And yet it only needs a certain obstinacy of the mind to look God's creation in the face and steadily refuse to go back beyond it or argue upwards from it. Man has the dreadful power of refusing to think. And for the most part when people do that they are only rationalizing what is really an attitude of the will; their will is enslaved to God's creatures and therefore their mind will not raise itself above God's creatures. For these people, then, God hides Himself. And for us too, who believe, He is in a sense hidden; for we know Him not in Himself but only by His effects; we only see as it were the robe which He wears, not Himself; and even of that robe we only see the lining; of how much poor stuff this visible creation is made, as compared with His invisible creation! He plays a kind of hide-and-seek with us; we have to keep on looking, or we shall miss Him. Even when we are nearest to Him in our prayer we are only conscious of His presence as something evanescent, like the feeling you have when you enter an empty room that somebody has just left.

Why does He do that? To challenge our faith. I am using the word in the broad, not in the strictly theological sense. He allows men, if they will, to doubt His existence—He whose very essence is to exist—in order that we who do believe in Him may feel the strain all the time, keep our heads upstream, not go stale, as we are apt to do in this probationary world, for the lack of effort. To seek His presence, still more to live as in His presence, is going to cost us something; we do not value things properly unless they cost us something. How are we going to set about finding Him, we who are so weak, so rudimentary in our prayer?

I always like that phrase which you come across immediately after the story of the Fall, when our first parents hid themselves in the garden from the presence of God. "They heard the voice of the Lord God walking in the garden at the afternoon air"; just that moment, I suppose, towards sunset when a hush seems to fall over nature; in London and New York they call it "the rush hour." It's as if that moment in the first cool of the evening was, in Paradise, a kind of tryst God kept with man; conscious as they were of His presence at all times in their innocence, it was then that He made Himself known specially, as a mother sends for her children during the hour before they go to bed. And on that miserable day when they sinned and knew that they had sinned, they hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God among the trees of the garden. They did, you see, what we are always doing, plunged themselves into the midst of creatures in order to forget their Creator. But He called them, even so.

We are all accustomed, if and as we can, to begin the day with God; it is well that we should. But some of the spiritual authors, including I think St. Francis de Sales, tells us that this hour in the early evening is, for some souls at least, the best time for the practice of interior prayer. Do not let us despise this practice of seeking for God's presence at some time in the late afternoon. It is then, I think, that it is easiest for some of us to shut our ears to the voice of creatures, and cultivate, though it only be for less than half an hour, the sense of God's presence; He will call, "Where art thou?" and no sense of unworthiness shall make us hide ourselves from Him.

|

Truly Thou art a God of hidden ways; God hides Himself, all the time, in His dealings with us men. After all, we should have expected, and mankind has always expected, that He would single out His own servants for particular favor; that a nation, a family, an individual who served Him faithfully would prosper, even in this life, more than their neighbors; be a standing advertisement to posterity that it is worthwhile to serve God. And of course now and again in history, when you read of the victories won by Constantine, or Clovis, or Charlemagne, you are tempted to think, "Well, that's all right; evidently, God does protect His own." But that mood of satisfaction doesn't last long. You haven't to go far to find instances in which a Catholic state has gone under, or years of patient work spent in building up a magnificent edifice of Catholic organization has been demolished at a blow. And so it is when you observe individual lives; how was it that So-and-so, who tried so hard to do God's will and live in His sight, was allowed to be the victim of continual misfortune? And, even in your own life, was it when you tried hardest that you were most rewarded? No, God hid Himself; would not allow you to trace, as if by a mechanical process of cause and effect, the connection of His favors with your endeavors for Him.

Just as we saw that God, in creating the world, left it open to us, if we would, to lose faith, so in His governance of the world God leaves it open to us, if we will, to lose hope. He lays Himself open to the blasphemy of those who say, "Well, if God does exist, He is either singularly limited in His powers or singularly wanting in watchfulness over the innocent and the devout." I always liked the story of St. Theresa, when she was carried away by the force of the stream while fording a river; if you remember, she felt Our Lord holding her down under the water and heard Him saying, "This is how I treat My faithful servants"; and St. Theresa, with a kind of holy cynicism of which only she would have been capable, answered, "That, O Lord, is why Thou hast so few." God hides Himself when we are in difficulties; how often we feel that! How often the Jews felt it; "Lord, why dost Thou stand far off? In days of peril and affliction, why does Thou make no sign?" And, what makes it worse, as if to emphasize this neglect, this seeming neglect, He encourages us to pray to Him, tells us to ask Him for everything we want, like children asking bread from their father; and then we pray, and nothing happens! How many despairs, how many blasphemies He incurs by treating us as He does!

What is the secret of it? Well, of course, there is one account of it which is easily given the moment you reflect on the possibilities; it is the answer given in the book of Job. Doth Job serve God for naught? asks the accusing angel; and it is when Job has lost everything he held dear, and serves God still, that the devil's lie is retorted on him. If piety always obviously paid, it would not be long before people took to being pious simply for what they could get out of it. But, as that story of St. Theresa suggests, there is a deeper meaning still. Do you remember how Elias, after he had triumphed over the false prophets of Baal, was hunted out by Queen Jezebel and fled for his life into the wilderness; how he came to Mount Horeb and made his complaint to God there? "I am all jealousy" (he says), "for the honor of the Lord God of hosts; see how the sons of Israel have thrown down thy altars, and put thy prophets to the sword; of these, I only am left, and now my life, too, is forfeit.' And then the Lord God passes by. "A wind there was, rude and boisterous, that shook the mountains and broke the rocks in pieces before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake; and after the earthquake a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire, and after the fire the whisper of a gentle breeze." It was as a silent whisper that Elias heard God's voice, and learned that all the passionate entreaties by which he had tried to storm heaven were misplaced; that it was in stillness he must wait for God; that prayer means, not bending God's will to ours, but bending our will to God's. God hides Himself from us in his governance of the world, and of our own lives, that we may learn to give up our own wills, and want, in life and in death, only what He wants, knowing that it is best for us. As we have made our act of faith in His presence, let us make now our act of confidence in His will.

Truly Thou art a God of hidden ways. God hides Himself in His Incarnation, not becoming merely man for us, but becoming a little child, a poor man, derided by His enemies, condemned to death as an imposter, dying a slave's death and at last lying in the tomb—God hidden not as man merely, but as a dead man.

Of course, just as it is true that God reveals Himself in His creation, so it is true that He reveals Himself in His Incarnation. As a candid mind which will fix itself upon the considerations which lie open to it ought to learn, from contemplation of the world around it, the existence of its Creator, so a candid mind reading the story of the Gospels and weighing the effect on history of what happened in Galilee hundreds of years ago, ought to see in the Incarnation God revealed afresh, revealed more intimately than ever. But you can, if you will, withhold your assent from the cogency of that reasoning process; people did, and do. In the Incarnation, as in Creation, God is half revealed and half concealed; that is the point. He revealed Himself, but not in a way to startle or to cow the imagination. "He will not strive nor cry out," the prophet wrote of him, "none shall hear his voice in the streets." Our Lord would be born, not as a Roman emperor but as a Galilean peasant; would live, not as a philosopher courted by all the sages of his time, but as a street-corner orator, producing a nine-days' wonder among the fishermen of Capharnaum; would die, not as a martyr but as an impostor; would rise again, to show Himself only to a handful of friends and return whence He came, leaving the world to forget Him if it would, to doubt Him if it would.

Oh yes, He did miracles; staggering miracles, in the presence of a great concourse of people sometimes. But He did them among His friends and His followers; when the Pharisees asked Him for a sign, there was no sign forthcoming. True God, in His Incarnation He hides Himself as much a possible behind the veil of His humanity; He will not even allow Himself to be called good—there is none good, He says, save God. You might almost say that He courts misrepresentation; eats with publicans and sinners to hide His sinlessness, agonizes in the garden to dissemble His omnipotence. There is nothing so divine about Our Lord, if I may use a paradox, as His humanness; as Creator, He hides Himself behind His creation, as Incarnate, He hides Himself in a creature-nature—it is a touch of the same artist's brush.

Why did He do that? Partly, of course, in order to exercise our faith; conviction should not force itself upon the mind; there should be a loop-hole, once again, by which doubt could creep in, if men were resolved to doubt. But it was partly to teach us a lesson of humility, of self-annihilation. He annihilates Himself, as far as that is possible, when you see Him as a baby at His Mother's breast; that is the point of the devotion to the sacred Infancy. The devotion to the sacred Infancy is not a sort of pretty-pretty affair, accommodating itself to our modern, sentimental pose of making a fuss about children; it is based on the amazing reflection that Omnipotent Godhead did hide itself in the form of a speechless, helpless Thing wrapped about in swaddling clothes, needing to have everything done for it, needing to be fed, to be protected, to be taught, all the time. If God annihilated Himself like that, how ought we do annihilate ourselves before God? And when He lies in the sepulcher, it is not simply that we might weep over the cruel hurts which brought Him there; it is that we might see the timeless, passionless, immutable Word of God hidden in the form of a dead Thing; Divine Personality united to a Corpse.

As a Child in the womb, as a Corpse in the tomb, He appeals to us to obliterate ourselves, to annihilate ourselves. We, who are nothing, must learn our own nothingness; must learn to kill that spirit of self-pleasing and self-assertion which mixes itself up even with our best desires, even with our most altruistic actions. We must learn, not merely to will what He wills, but to will what He wills only because He wills it; to make ourselves His tools, His playthings; die to ourselves that He may live in us.

|

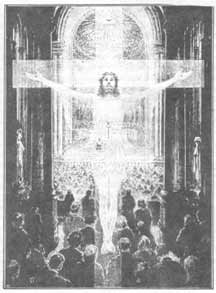

Truly Thou art a God of hidden ways—God hides Himself still more effectively, still more intimately, in the Holy Eucharist. Indeed, you may say that this mystery sums up and exceeds those other mysteries which we have been considering.

God hides Himself in creation, in the sense that you cannot read in it the evidence to prove His existence unless you will use your reason over it. If you will use it, reason points to God as surely as the compass points to the magnetic pole. But where He hides Himself in the Holy Eucharist, reason gives no indication, is powerless to infer. It can tell us, what the senses cannot tell us, that there is an underlying reality which sustains, in natural objects, those outward appearances which impress themselves on our senses. But, that when the priest has spoken the words of consecration, the reality of Christ's Body and Blood becomes present—over all that reason has no message to give us; nothing, here, will point to God's presence except the divining-wand of faith. If, then, God as hidden in creation allows men, easily and frequently, to blaspheme him by saying there is no God, so, as hidden in the Holy Eucharist, He allows men, still more easily, still more frequently, to blaspheme Him by saying there is no God here. More effectively than ever He shrouds himself from profane eyes, that He may reveal Himself more effectively than ever to the eyes of faith. When we honor Him in His Sacrament, we have to make reparation not only for the many who deny His existence, but for those, still more numerous, who deny His sacramental presence.

God hides Himself in His governance of the world, in the sense that He does not ordinarily allow us to see which are His chosen friends by singling them out for special favors. He makes His sun rise on the evil and equally on the good; His rain fall on the just and equally on the unjust. But His operation on men's souls when He comes to them in the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist is a sun which fosters supernatural life in those who receive it worthily, rain which gives them growth. It is a sun which dries up all life in the souls which receive it unworthily, rain which brings with it only corruption. But all this is hidden from our knowledge; we cannot tell whether the gift brings life or death to the communicant who is kneeling next to us. In His operation, as in His presence, God hides Himself here, more effectively than ever.

And if, in His Incarnation, God stooped towards us and condescended to our level by uniting His Divine Nature with a human nature, which, though created, was created in His image, was part of His spiritual creation; how much lower He stoops, how much more He condescends, when He hides Himself in the Holy Eucharist, veiled under the forms of material, insensible things! If in His Incarnation He gave Himself up into the hands of men, allowed them to overpower Him and control His movements, how much more generously does He give Himself in the Holy Eucharist, putting Himself in the priest's hands and exposing Himself to sacrilege at the whim of His enemies! Hidden not only from sense but from reason, hiding from us not only the principle on which He bestows His benefits but the actual bestowal of them, yielding Himself to us not merely in the form of a servant, as in His Incarnation, but in the form of an instrument, available at our will, surely He finds in the Holy Eucharist the best hiding place of all.

And what attitude should all that provoke on our side? Surely one of utter resignation into His hands. Our Lord, in the tabernacle, puts Himself at our disposal, ready for our worship, if we will come to worship Him, ready to give life to our souls, if we will receive Him, but all the time, however we neglect Him, offering Himself as Victim to His heavenly Father. We on our side are to put ourselves entirely at his disposal; ready to do all He would have us do, ready to suffer all He would have us suffer, but all the time, whether He calls upon us for such service or not, offering ourselves as victims to the same Heavenly Father, in harmony with His aspiration, and in union with His Sacrifice.