Catholic Roots in the United States

Fr. Christopher Hunter

While the roots of the United States may not be Catholic, it would be wrong to assert that this applies to all areas of this country. There are some very large parts of the United States where the Catholic Faith has existed from the beginning. The Southwest, for example, and large sections of California were explored by the Spanish who brought priests with them, planting the Faith wherever the opportunity presented itself. It was the Franciscans who almost exclusively established Catholicism in the Southwest. By 1626, 27 missions and 43 churches had been established and 34,000 Indians baptized in New Mexico. Among the names we remember are Fr. Augustine Rodriguez, Marcos de Niza, Fr. Alonso Martinez, Fr. Geronimo de Zarate Salmeron and Fr. Francisco Garces.

In California, the great mission system was established likewise by the Franciscans who took over the 18 missions established by the Jesuits in lower California after the latter were expelled in 1767 by King Carlos III of Spain. The moving force behind the Franciscan missions was Fr. Junipero Serra. For 15 years he labored among the Indians and at the time of his death in 1784, he had established nine missions between San Diego and San Francisco.

Some mention should also be made of the Dominicans who established seven missions before the year 1840.1

Another large area, and the one we shall concern ourselves with here, is the Pacific Northwest. We perhaps don't think of this area as Catholic, but at least in its origins it was. Within the area of Washington, Idaho and western Montana, much missionary activity took place which resulted in firmly planting the Faith in this wilderness area.

The pioneer moving force behind this Catholic evangelization was, of course, Fr. Pierre Jean DeSmet, S.J.

One of 22 children, he was the son of a well-to-do shipbuilder, Joost DeSmet. Born on January 31, 1801 in the Belgian town of Termonde, he was born with a rugged constitution that would serve him well in the vigorous life ahead of him. In the preparatory seminary at Mechlin, his classmates said: "he possessed sound judgment and that one day he would become a man of action."

Father Desmet's missionary work in the United States began as a result of a visit to his seminary by Fr. Charles Nerinckx, a Jesuit from Kentucky, who was appealing for priests to work in America with both Whites and Indians. DeSmet volunteered, came to the U.S. and entered the Jesuit novitiate at Whitemarsh, Maryland in 1821. Two years later he was ordained to the priesthood by Bishop Rosati at Florissant, Missouri. His first assignment was to open a mission among the Potowatomie Indians in Kansas.

Although it was to be some years before his missionary work in the Northwest was to begin, events were already unfolding that would bring him to this unsettled wilderness.

The Indians of the Pacific Northwest were to first hear stories of the Black Robes from the Iroquois. Although an eastern and Canadian Indian tribe, the Iroquois were both voyeurs and fur traders in the Pacific Northwest. In fact, between 1783 and 1821, 40% of the fur traders of the Northwest Company were Iroquois. These fur trading Indians had long since been exposed to the Jesuits who had already traveled among them as far back as 1642 in Montreal. Consequently, the Indian tribes of the Pacific Northwest became desirous of having these Black Robes come among them to teach the Faith. Chief Big Face of the Flathead tribe said: "We must find the Black Robes who talk to the Great Spirit. Tomorrow we send warriors to them."

Fr. Ravalli's Home — St. Mary's Mission |

Thus it was in 1831 that the first delegation of 4 Indians was sent to St. Louis. Upon arriving they spoke with Bishop Joseph Rosati and the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, General William Clark, of Lewis and Clark fame. The Bishop had to sadly tell them that he simply did not have the priests to send them. However, both the Bishop and General Clark were impressed with their religious zeal.

This was the first of four delegations sent to obtain priests. The next two, sent in 1835 and 1837 produced no results, the latter delegation being wiped out by an attack of Sioux Indians.

Finally, in 1839 two more Indians set out which resulted in a meeting with Fr. DeSmet at St. Joseph's Mission, Council Bluffs, Iowa. In 1840, Fr. Pierre DeSmet, the long-awaited Black Robe met a welcoming party of Flathead Indians at Green River in southwestern Wyoming. Of this meeting Fr. DeSmet was later to write: "Our meeting was not that of strangers but of friends. They were like children who, after long absence, run to meet their father. I wept for joy in embracing them, and with tears in their eyes they welcomed me with tender words, with childlike simplicity."

From here they continued up the Snake River, across the Continental Divide until they met the main body of the Flatheads near the headwaters of the Beaverhead. When they reached the Beaverhead-Jefferson River, Fr. DeSmet said the first Mass in Montana and likewise gave his first sermon to the Indians.

Father DeSmet and his companions finally finished their long journey on September 24 when they reached the Bitteroot Valley in present-day Montana. Here was established, for the Flathead Indians, he first mission in the state.

Before his death on May 23, 1873, he was still engaged in his missionary work which took him to widely scattered areas. He visited tribes in Kansas, Idaho and Utah, founded another mission in Williamette Valley, Oregon, labored among tribes in South Dakota and worked among the Mandans and Gros Ventres in North Dakota.

Father DeSmet is buried at the Jesuit novitiate at Florrisant, Missiouri on the banks of the Mississippi.

St. Mary's Mission

Located on 314 acres, St. Mary's Mission is today opened to the public in Stevensville, Montana. On it can be seen the original buildings which include the chapel itself, slightly enlarged from its original size, the home of Fr. Ravalli, about whom we shall have more to say later, and the home of Chief Victor, the Indian Chief of the Flathead tribe.

Over the years since it ceased being an Indian mission, white people occupied the two residences and altered their structures. These were later restored to their original appearance.

As these buildings fell into disrepair considerable restoration work has been required and is still continuing. The moving force behind this work has been Mrs. Lucylle Evans without whose energetic leadership the mission today might be, instead, the site of a parish center rather than an historic Catholic mission.

The author of two books on the Catholic history of the area, and presently writing a third, she became the logical person to lead in the restoration. Begun in 1976, the work was completed in 1983 and opened to the public the same year.

Located on the mission property is a small cemetery which contains the grave of Father Anthony Ravalli, S.J., the priest who is most associated with St. Mary's Mission. One of at least eight other priests Father DeSmet brought over to assist in missionary work, Fr. Ravalli was a gifted man whose talents and training qualified him as a physician, architect, builder, artist, missionary, mechanic and craftsman. Needless to say, he was able to employ all these skills fully in the primitive Northwest.

Fr. Ravalli was first called to St. Mary's in 1845 to replace a Fr. Zerbinati who had recently died. Fr. Ravalli was there until 1850 when the Jesuits abandoned the mission for a while. In 1866, it was re-opened and Fr. Ravalli was again assigned there where he stayed until his death in 1884.

Because of his versatility, Fr. Ravalli was responsible for successfully farming the land, improving the method by which bread was produced, established the first grist mill in Montana, built a saw mill, extracted alcohol from plants to be used as medicine, and was Montana's first doctor.

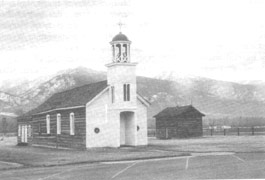

St. Mary's Mission, with Fr. Ravalli's house to the right. The beautiful Rocky Mountains are in the background. |

Fr. Ravalli was not only well-liked by his contemporaries but is one of Montana's most beloved citizens. Ravalli County, Montana is named after him as well as the town of Ravalli. Even the Protestant historian Chittenden felt compelled to speak of him as "one of the noblest men that ever labored in the ranks of the Church in Montana..."

Before leaving St. Mary's Mission, it should be noted that two apparitions are reported to have taken place there. The first to a thirteen-year-old Indian girl named Mary who is recorded to have said: "There is no happiness on this earth; happiness is only to be found above; I see the heavens open and the Mother of Jesus Christ invites me up to her." Then, turning to the startled Indians, she said: "Listen to the Black Robes when they come: they have the true prayer; do all they tell you. They will come and on this very spot, where I die, will build a house of prayer." This prophecy came true.

The other account is of a young orphan boy named Paul who, a few hours before Midnight Mass on Christmas eve, saw Our Lady and left a description of her. The boy had entered the hut of another in order to learn his prayers but as a result of the vision knew them at once.

It was Fr. DeSmet who reported this apparition which, it would seem, is authentic. The child had no previous knowledge of the kind of dress this woman wore and his testimony was consistent each time a new person interrogated him.

Cataldo Mission

Chief Circling Raven of the Coeur d'Alene Indians is said to have had a dream in which he was told of the Black Robes and to welcome them when they come. These Black Robes would teach his people about the "Great Spirit". However, they did not appear during his lifetime but as he was nearing death, the Chief passed this message on to his son. It was during the son's lifetime that the Black Robes came to the Coeur d'Alene Indians.

The Cataldo Mission |

In 1842, on a second trip from St. Mary's Mission to Colville, Washington, Fr. DeSmet crossed the Bitteroot Mountains and came into "a fertile, lovely valley, stretching westward hundreds of miles." This valley was the home of the Coeur d'Alene Indians.

Fr. DeSmet found these Indians to have a high moral code, were not warlike and, unlike most Indians, were neat. In fact, they had already adopted some Christian ideas before Fr. DeSmet's arrival, probably from contact with the Iroquois.

On his first visit to these Indians, Fr. DeSmet wrote: "Never has a visit to the Indians given me such consolation and nowhere have I seen such unmistakable proof of true conversion, not even excepting the Flatheads in 1840."

Fr. DeSmet had Fr. Nicolas Point and Brother Huet establish a mission among them. This first mission was established on the St. Joe River in 1842 and was intended to be permanent. However, due to the land being flooded each spring, it was finally abandoned in 1846.

Sometime between 1844 and 1846, Fr. DeSmet chose a new location for the mission, this time upon a hill. In the meantime, he had gone east for a tour of the United States and Europe to raise money.

Fr. Ravalli designed the second mission and construction on it began in 1848. By the winter of 1849-50 the building was already in use. Built only by those Indians "who were exemplary in conduct," the chapel was designed to be 30' high, 90' long and 40' wide. As no nails were available, the uprights and rafters were joined with wooden pegs.

In 1850, St. Mary's Mission was closed and Fr. Ravalli was placed in charge of the Coeur d'Alene Mission. His many skills not only allowed him to design the chapel but to also improvise a whipsaw to cut the needed wood from pine trees, construct three altars with hand-carved decorations, and carve statues of the Blessed Mother and St. John the Evangelist from blocks of wood to adorn the tops of two small pillars at the entrance of the sanctuary. By 1853 the mission was opened for services.

Both the Coeur d'Alene and Flathead Indians were amazing for their conviction that the Catholic Faith was the only true Faith and their loyalty to it, once it was learned, was unswerving. Attempts were made by Protestant missionaries to evangelize them, but these Indians were quick to see they were not the Black Robes and sent them on their way! Thus, the Protestants continued westward and converted some of the Nez Perce and many Oregon tribes.

Probably the most outstanding member of the Coeur d'Alene tribe was Louise Sighouin, a daughter of the Chief of the Coeur d'Alene Indians and baptized by Fr. DeSmet in 1842. Noted for her piety and modesty, she spent many hours instructing both the children and the aged in the Faith. Every day she visited the tepees of the sick ministering to their needs. She is reported to have died in the odor of sanctity.

The Cataldo Mission, as it is called today, is named after Fr. Joseph Cataldo, S.J., who came among the Coeur d'Alene's in 1865 and later founded missions among the Nez Perce Indians, re-established the mission at the Yakima Reservation in 1870 and became Superior of all the Rocky Mountain Missions in 1877, making the old Coeur d'Alene Mission his headquarters.

By 1877, however, the Mission's days were numbered. The United States government boundary line for the reservation did not include the mission. In addition, there was not enough arable land left to keep the Indians in farming. Reluctant to leave their land and mission, they migrated to DeSmet, Idaho at the urging of the Black Robes whose advice they still heeded.

St. Ignatius Mission

The last of the missions we shall concern ourselves with is the mission of St. Ignatius, located about forty miles north of Missoula, Montana. It is situated in the Mission Valley with the Mission Mountains to the east and the hills of the National Bison Range to the west, at the southern end of the Flathead Indian Reservation. The town grew up around the mission as is so often the case. By 1895 the mission complex was so extensive that it included a second mission church; two Jesuit residences, one of which was later turned over to the Ursuline sisters; an industrial arts school, and the present mission church, which has been called "Montana's own Sistine Chapel" because of the fifty-eight beautiful murals it contains. Begun in 1891, its construction took two years and was built by both the missionaries and the Indians who used bricks made from local clay and trees cut in the foothills and sawed at the mission mill. The chapel measures 120' by 60' with a belfry reaching nearly 100' in height.

The original mission settlement was established in the spring of 1845 by Fr. DeSmet and Fr. Adrian Hoecken near the present Washington-Idaho border. However, the location proved unfavorable and, at the request of the Indians, the mission was moved nine years later to its present site.

By the spring of 1855, nearly a thousand Indians of various tribes had settled near the mission.

What has been called the "golden age" of the mission were the years between 1875 and 1900. The mission obtained a printing press and published a Kalispel Dictionary and Narratives From the Holy Scripture in Kalispel. The mission's two schools continued to grow, an agricultural school for the boys and a boarding school for the girls. In 1890 the Ursuline Sisters arrived and began a school which eventually became both a grade and high school.

Today the mission consists of four buildings: the church, two of the original residences and the present rectory. The mission is open year round and over 50,000 tourists stop in during the summer months, usually on their way to Glacier National Park two hours north.

In 1973 the mission was declared a National Historic Site.

Father DeSmet

Although it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the lives of the personalities mentioned, it would seem almost misleading to end without expanding upon this remarkable man. He has been called "probably the greatest missionary of the nineteenth century". Besides the several missions he established around the Pacific Northwest area, he had an amazing ability to win the confidence of all the Indians he came in contact with. He was even trusted by the warlike Sioux and Blackfoot who warred against the other tribes that Fr. DeSmet was laboring among. At Fort Lewis in 1846, he successfully concluded a peace treaty with the Crow and Blackfeet Indians, leaving behind a mission.

The United States government requested that he accompany General Harney to the Oregon and Washington territories where it was feared an uprising would take place. But peace was maintained.

On at least two other occasions the government requested his efforts to keep peace. In fact, the peace treaty signed on July 2, 1868 by all the chiefs of the Sioux tribes, effected by Fr. DeSmet, has been described as "the most remarkable event in the history of the Indian wars."

The Catholic Encyclopedia tells us that:

"On behalf of the Indians he crossed the ocean nineteen times, visiting popes, kings, and presidents, and traversing almost every European land. By actual calculation he traveled 180,000 miles on his errands of charity."

The writings he left behind are extensive and give a detailed account of Indian life. His geographical observations have only needed to be corrected in minor details by subsequent scientific observation.

Even Protestant writers have said that he was the sincerest friend the Indians ever had.

1. It would be a mistake, however, to think that the establishment of the Faith in these areas is a story of glorious Catholic explorers and missionaries eager to plant Catholicism in the hearts of childlike savages.

Coronado was apparently reluctant to explore this area, which is why Marcos de Niza was sent out ahead of him.

Don Juan de Onate, who established the first permanent Spanish settlement and mission in New Mexico in 1598—San Juan de los Caballeros—had visions of conquering new territory and set off to do so in 1601. The people in the settlement were left unprotected and civil discord broke out and the mission was largely abandoned.

In 1680, under the leadership of an Indian of the pueblo of San Juan, Pope led a rebellion against this same settlement. Many were massacred and the survivors were driven back across the Rio Grande. This attack wiped out most of the original mission work in the Southwest. Among the things destroyed were precious documents, the loss of which has since made the reconstruction of Southwest history difficult.

In 1767 a controversy broke out between the Franciscans and the Jesuits, resulting in the expulsion of the latter and the confiscation of mission property by the Spanish government.

The missions of Arizona declined after 1800 and in 1828 the Mexican government ordered their abandonment. From this time until 1859 "there were no signs of Christianity in Arizona other than abandoned missions and ruined churches." (See the Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. II, pg. 4.)

Things were hardly better in California. The first settlement which was again made by the Franciscans in 1525 at Santa Cruz Bay had to be abandoned due to their inability to support themselves.

A second effort was made in 1596 when four priests and a lay brother had to abandon their settlement within a year due to hunger and the hostility of the Indians "who proved to be on the lowest plane of humanity."

A third attempt was made by the Jesuits which lasted two and a half years. But the whole undertaking was a bit tenuous and for want of supplies and the high cost of maintenance the Spanish withdrew, much to the sorrow of the catechumens.

The Domincan missions were secularized by the Mexican government in 1834. After taking control of the missions the Indians scattered and the missions decayed so much that the government in 1856 declared them to be in ruins.

In 1822, California became part of the territory of Mexico, a date which marks the decline of the missions. The government began interfering with them and in 1834, the secularization of the missions resulted in virtual confiscation. The priests were deprived of their lands and the Indians dispersed, many lapsing into barbarism and the missions were destroyed.