In the Service of the Church

In Homage to His Excellency Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre

|

The actions of Archbishop Lefebvre became an integral part of Church history well before the Second Vatican Council was convened. How did this come about? Over many years Divine Providence prepared the Archbishop as His instrument. After his ordination to the Holy Priesthood in 1929, He called him to the Congregation of the Fathers of the Holy Ghost, thus permitting him to gather experience and form deep impressions as a missionary in Africa. His Grace became conscious of one thing: neither the human soul nor society can be cured of their wounds, or return to the Triune God of their origin, except by the redeeming love of Jesus Crucified, as Priest and as Victim present in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Consequentially, if one seeks to renew the Church in the Holy Ghost and preserve the nations from self-destruction, faith in the divinity of Christ is necessary above all else. Faith, in the purifying, healing and sanctifying virtue of the love of God made Man, is the program of the episcopal ministry that the Church itself confided to Archbishop Lefebvre. With all his heart he preached the supernatural order from the beginning of his episcopacy, September 18, 1947. He forcefully brought to reality the truths of our Faith as a missionary in Gabon, Bishop of Dakar, and Apostolic Delegate of the Holy See. He did not preach anything except the Holy Gospel, did not announce any Faith but that of the Apostles, and he transmitted what he had himself received. According to the Catholic author, Michael Davies, he has done, in this century, more than anyone else in the religious domain (or even the civilian domain), for the Black Continent. Today still, the aged faithful in Gabon tell that when the good Father Marcel left them, responding to the appeal of his superior in 1945, they had the impression that the Good Lord Himself was leaving them. In his own words, he lived through three terrible wars: the First World War, with the destruction of the Catholic States of Europe, especially the Austrian Monarchy; the Second World War, with the world-wide success of Marxism; and the third, from 1962 to 1965, with the victory of naturalism, of progressivism and of Liberalism at the Second Vatican Council. In this situation of progressed apostasy, of betrayal of the supernatural order of grace, a situation humanly without end, and in the midst of painful sufferings, on the Feast of All Saints 1970, he gave birth to the Priestly Society of St. Pius X. He thus gave testimony before the entire world of the fruition and sanctity of the Holy Church. An accomplishment of which certain bishops dream and others only speak, he has made reality, in Him Who gives fortitude. The Athanasius of the twentieth century, he gives to the Church (which, in human terms, is dying) a new generation of well-instructed, pious, zealous priests. He thus awakens Christianity to a new life in the humblest of beginnings. He sees that Christian civilization can only build itself with the Altar and Tabernacle as its foundation; that the Church cannot live without its source in holiness. He fulfilled his duty as a Catholic Bishop in the midst of innumerable attacks, defamations which tormented his episcopal heart—not because of himself, but because of the Church. As an untiring missionary, he still crosses the oceans—comforting, encouraging, building. He strengthens his brothers in the Faith, and inspires vocations of priests and religious men and women. He encourages youths and families so that the King Who has been dethroned may again be the King of minds, of hearts, of families, of schools, of states and, above all, of the Church. Men everywhere consider themselves better for having only met him. In return, by prayers more numerous probably than for any other bishop in the world, they strive to console this good shepherd, and to compensate him for his pain. These few words express the simple testimony of a son for his father in Christ. Father Franz Schmidberger On the Feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, |

The lines which follow are neither a biography of the Archbishop, nor an account of all his work in his service of Our Lord. How could we encapsulate over forty years of fervent episcopal service in a few pages? This is only an effort to make known certain aspects of a life which is totally consecrated to God.

During his life, Archbishop Lefebvre has shown himself to be the instrument of Providence, not acting on his own will, but resolved to accomplish the mission which has been entrusted to him. To evangelize, to safeguard the teachings of Revelation, of the Magisterium and of the Tradition of the Church, to work for the restoration of the Kingship of Our Lord over souls, cities, and nations, and to instruct priests in order to insure the continuity of the priesthood and the perpetuation of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass—these have never ceased to be his sole preoccupation.

In his simply furnished office, identical to those of the seminary professors, Archbishop Lefebvre is seated facing a large Crucifix towards which he often looks. The room is encircled with bookcases which contain his frequently used copies of the Summa of St. Thomas Aquinas, and the Catechism of the Council of Trent. In August of 1986 he organized these bookcases, labeling with his own hands all those documents which have marked the course of his life and the conciliar period.

The Lefebvre Family in 1922 Marcel, on the left, and his elder brother, Rene, stand behind their parents |

How can we translate the rectitude, the fidelity, the faith, of this priest of Jesus Christ who is so exceptionally active? At the end of the meal, following the celebration of his episcopal consecration, his brother, René, commented: "If our father was here I think he would say, 'In the family we have been men of duty; we have always done our duty; it matters little what is going to happen as a result.'"

Just as he has never forgotten the Christian education that he received from his parents and his professors, the words of René, who played such an important role in the orientation of his apostolate, have never been erased from his memory. During his life as a missionary and his forty years as a bishop, the Archbishop has not ceased to be faithful to his duty. He will not turn aside or make concessions, even at the price of great personal suffering, namely being opposed by the highest authorities in the Church who promulgate the errors of Modernism. He acts in order to save the Church from self-destruction. "I have spent my life building up the Church. I cannot now contribute to its destruction."

The pain of this cruel trial hurts him immensely. He has felt himself alone in combat for over twenty years now. He has been the object of persecution by the successors of the Throne of Peter for behavior which has not been modified since he was last praised [for the same behavior] by Pope Pius XII.

Why has he not given in to work which would have been easier? Why has he not done like the others? Why has he not taken refuge in obedience? At his Priestly Jubilee in 1979, His Grace responded to this question: "Because I have seen what the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass can do to the conquest of souls. I have seen villages transformed not only spiritually, but also in the area of social development."

He communicated this same message at the beginning of the year, addressing himself to the seminarians at Zaitzkofen, Germany. The Archbishop stated:

I speak, for example, of a rather typical but not isolated village of Fadiouth in Senegal. It is situated on a small island whose population was almost entirely converted to Catholicism. There were two or three Moslem families out of 2,500 inhabitants, and the difference between the homes of the pagans and the assembly of converted could clearly be seen. There reigned an atmosphere of neatness, of order, and of discipline. The houses were well taken care of, the families were indeed united, and there were many good homes. Sunday Mass was a marvel! In those times the men were still on one side and the women on the other. All were clean, having arranged their personal appearance and they were chanting canticles with much fervor. It was an admirable Christian atmosphere. This demonstrates very well the fortunate consequences of evangelization, which are manifested not only in the spiritual domain but also in the temporal.

If someone asks him about the origin of his missionary vocation, the Archbishop does not answer as one might expect.

No, the reasons given by others are not completely factual. I was not much attracted by the distant missions. I was very much at ease at the parish of Marais-de-Lomme, to which I had been assigned by Cardinal Liénart. However, my brother, René, had always thought about the missions, even from his seminary days. He was far more vigorous physically than I. He was energetic, in excellent health, and interested in sports. He was truly animated with missionary zeal. He thus left the French Seminary in Rome in order to finish his studies with the Holy Ghost Fathers. He left for Gabon in 1927. I was satisfied to have been assigned to a parish. I was happier to be in the midst of a Christian community, rather than travel a great distance, to go from village to village.

But my brother wrote me letter after letter, saying there were too many priests at Lille and to come to where they were submerged in work. My pastor had not been exactly excited to see me arrive. He already had a vicar and thought that the two of them were too much, especially for the finances of a parish consisting of 10,000 people.

The Archbishop could easily have brought about a very peaceful career, but he did not fear. He finally allowed himself to be persuaded by his brother to join him in Gabon. The Archbishop continues:

Before this, I should say that I was very much attracted by the Cistercian life. On several occasions I frequented the Trappist monastery of Wlestvleteren in Belgium, where one of my uncles lived. I went to see him and this life attracted me quite a bit. I would have rather even entered there as a Brother. I found these Brothers so admirable, so close to the Good Lord. In their simplicity and their candor, they reflected a heavenly happiness. But Providence had decided otherwise.

* * *

|

|

He was born in Tourcoing, France, on November 29, 1905, to exemplary Catholic parents, René and Gabrielle Lefebvre. After his baptism, Madame Lefebvre, while embracing her child for the first time, said: "This child will have an important rôle to play in Rome, with the Holy Father." She thus foresaw the future ecclesiastical career of her son.

She knew, as did her husband, how to impart a demanding and complete education which included not only the principles of the Christian life, but also the necessary bases of a deep piety. This is why, from this family of eight children, two, René and Marcel, became priests in the Order of the Fathers of the Holy Ghost, and three of the girls became nuns: Jeanne, in the Society of Mary Reparatrix; Bernadette, who became Mother Marie Gabrielle, Superior of the Sisters of the Society of St. Pius X at St. Michel-en-Brenne (France); and Christiane, Superior of the Carmel of Quiévrain (Belgium). The three others, Joseph, Michael and Marie-Thérèse, for their part founded families of many children.

The atmosphere of the family, the spirit of the College of the Sacred Heart (where he completed his primary and secondary studies), the life of prayer (he used to serve Mass every morning at 5:30), the apostolate of the sick to which he devoted himself in the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, and his love of study, predisposed young Marcel favorably to a priestly vocation.

A young Father Marcel, arriving in Africa |

At the French Seminary in Rome, he was noted for his piety, his spirit of obedience to his superiors, and his hard work. Having held positions of responsibility reserved for model students, he received his doctorates in philosophy (late 1925), and theology (1929) at the Gregorian Pontifical University. On September 21, 1929, he was ordained a priest forever.

In October 1930, he was appointed curate of the parish of Marais-de-Lomme, a working-class suburb of Lille, and he rapidly won the affection of his poor parishioners by his priestly zeal and devotion. "This young priest of shining faith," as one described him, seemed destined to be appointed a professor in the diocesan seminary. However, Divine Providence had other plans for him in making him discover, thanks to the letters of his brother, the missionary, the immense task which awaited him in Africa. Responding to the divine call, Father Marcel Lefebvre entered the novitiate of the Holy Ghost Fathers, in 1931.

After making his first vows, Father Lefebvre embarked upon the "Fouauld" for Gabon, in October 1932, to meet his brother René.

In November 1932, Mgr. Tardy, Bishop of Libreville, appointed Father Lefebvre Professor of Dogma and Scripture at the major seminary which brought all the seminarians of French Equatorial Africa together. In 1934, Father Fauret, appointed vicar general, handed over the running of the seminary to him, and he became the superior. Preparing seminarians for the Holy Priesthood had become, and would forever be, the most important pre-occupation of his life. His colleague, Father Berger, was later to say of him that he was "firm and temperate, very particular in his opinions and his decisions, always remarkable in his organization and use of resources."

Bishop Lefebvre in 1947, with Cardinal Liénart |

Indeed, he was successively a teacher, builder, steward, printer, driver and electrician—combining his skill at manual tasks with a taste and special ability for the intellectual formation of his pupils. Despite his firmness and his exacting nature, none of his seminarians had any complaints to make about him. "Even those who had to experience the rather harsh discipline admit that, after all, he was in the right," emphasized Father René.

During this period, Father Marcel wrote:

If there was anything that did not attract me, it was the responsibility of being a professor. 1 would have indeed preferred the ministry, but ultimately, we think one way and Providence disposes in another. I could very easily see myself becoming a pastor of a parish of two or three thousand people, taking care of them, baptizing the children, giving the Sacraments, trying to sanctify them—and then, I find myself as a missionary in Gabon!

Beloved of the Fathers and his pupils, confessor to Mgr. Tardy, he founded an educational system which today allows the seminary to count a cardinal, three bishops and two heads of state among its former pupils, a proof of true progress which civilized Africa, bringing about, little by little, the disappearance of polygamy, ignorance, the reign of witch doctors and the superstition everywhere present at that time.

This period, from 1933 to 1947 saw the Catholic population of Gabon rise from 30,000 to 105,000 faithful, and an increase in the number of churches, schools, and hospitals in the missions.

For Father Lefebvre these years were a time of family sadness, despite his meetings with René in Gabon and Marie-Gabrielle in the Cameroons. In 1938, his mother died. In 1943, his father was arrested; and in 1944 he died in the Nazi concentration camp at Sonnenburg. One of his father's last letters has survived, showing him to be a profoundly Catholic man. In this letter the Archbishop's father commends his family to the Most Holy Virgin, "who will deign to bless my family, which must remain consecrated to her, be totally devoted to her, and seek the reign of her Divine Son through her."

Until 1945, Father Marcel gave the full measure of his missionary apostolate at Lambarene and then N'Djole. In order to more effectively reach the people he evangelized, he learned their language, Fang. When he returned to Gabon forty years later he greatly surprised the old ones by showing that he had not forgotten their language.

|

"Between 1947 and 1962, Monseigneur Lefebvre, a tireless apostle, changed the face of Senegal." —Jean Delacourt |

Archbishop Lefebvre arriving in Dakar, 16 November 1947 |

In 1939, after seven years on this mission, he left for France. The declaration of war forced his ship to make a stop at Freetown in Sierre Leone on the west coast of Africa. He set out again at Dakar, debarked at Bordeaux, from which he reached Tourcoing (the town in which he was born), and he embraced his father (whom he would not see again), and his young brothers and sisters. He went to gather his thoughts at the grave of his mother, but the hostilities began and he returned to Libreville.

After a bombardment of almost a month, the Free French forces, supported by the English, penetrated to Libreville and approached Donguila. Father Marcel learned that Bishop Tardy, along with several other missionaries, had been imprisoned.

A Message that Changes All

1945 was the year in which his provincial recalled him to France. He was appointed head of the training school of the Holy Ghost Fathers at Mortain. The last months of his stay in Gabon were nevertheless busy. This period consisted of missionary work, catechism, sermons, administering the sacraments, contacts with the non-Christians, and long, hot days in the confessional. Calling this period to mind, Archbishop Lefebvre declared:

Obedience is a good thing. I returned, pleased to think that I was only doing my duty. I did not regret it. At that time there was talk in France of the seminaries, of the prevalent atmosphere in them, a rather undisciplined atmosphere, of a love for the new, a feverish, active youth.

With conviction and enthusiasm to make of the young people especially entrusted to him new priests, he applied his experience and his gifts as a teacher to impart to these students of philosophy, the same missionary spirit which, twenty-five years later, he imparted to the members of the Society of St. Pius X. It is a spirit of fidelity to the Church, joyful and simple, dynamic and industrious, of conquest and evangelization in silent sacrifice—in short, the Catholic spirit.

On June 12, 1947, Pope Pius XII named him Vicar-Apostolic to Dakar. He left to prepare himself for this serious mission by making a retreat at the Abbey of St. André de Bruges, where he was close to one of his relatives, the celebrated liturgist, Dom Caspar Lefebvre.

Forty Years Ago

On September 18, 1947, on the Feast of St. Joseph of Cupertino, Father Marcel was consecrated bishop by Cardinal Liénart, Bishop of Lille. It was in his native parish, Notre Dame de Tourcoing, that he became for all time Bishop Marcel Lefebvre. On November 16, 1947, he took up his functions at Dakar, where the civil and military authorities, the settlers and the faithful greeted him solemnly. A year had not yet gone by when, on September 22, 1948, Pius XII made him the Apostolic Delegate for French-speaking Africa, eighteen countries. This high responsibility was equivalent to that of an accredited nuncio in the western countries. For eleven years, until 1959, the Archbishop carried out an exceptional task. All testimonies are in agreement on this point.

|

|

In those years, Archbishop Lefebvre, as the first Archbishop of Dakar and as Apostolic Delegate, had created four episcopal conferences, twenty-one new dioceses, and apostolic prefectures, set up major seminaries in the countries under his jurisdiction, and increased the number of native priests. Further, he developed the Catholic press by founding modern printing shops, organizing Catholic Action with many cultural centers and endowed each mission with a dispensary, developed primary and secondary schools (1947: 2,000 pupils distributed among nine primary schools; ten years later, 12,000 pupils in fifty schools; the number of secondary schools was up from four to twelve, welcoming 1,600 pupils).

He met with the Holy Father at least once a year, and was brought to participate in the nomination of thirty-six bishops. It can also be said that he prompted Pope Pius XII to write the encyclical Fide Donum in favor of the missions and missionary vocations, calling on the dioceses of the western world for their financial help. Certain paragraphs of this encyclical directly translate the concerns that Archbishop Lefebvre had expressed to the Sovereign Pontiff in a perfect spirit of free apostolic cooperation. Pius XII chose him to be the first Archbishop of Dakar, and he was solemnly installed in his new functions on September 14, 1955, by Cardinal Tisserant.

His Holiness Pope John XXIII with Mgr. Lefebvre, 1962 |

The pastoral letters of Archbishop Lefebvre show the complexity of the task of building a Christian society. His first letter attacks the key problem: ignorance in religion. In this letter written a month-and-a-half after his arrival, he recalls the duty to study the catechism and the Scriptures, and the obligation laid upon parents to teach them to their children. The second letter is directed against impiety and invites the faithful "to work with all our strength for the reign of Our Lord Jesus Christ in civil society, and in the family, to prevent the type of terrible evils that were afflicting Hungary and Rumania, and being inflicted upon ourselves and our homes."

Other subjects were discussed in later letters: the Christian family, social and economic problems, the problems of Communism which threatened Africa, of anti-clericalism and its dangers.

Having been Apostolic Delegate for all French-speaking Africa until 1959, and after fifteen years as bishop, he left the Archdiocese of Dakar in the hands of his spiritual son and former pupil, today a Cardinal, Hyacinthe Thiandoum, "having served the Church with all his heart and all his Faith" (a letter of Archbishop Rolland, Bishop of Antsirabe).

In Europe: Tulle, Superior General, The Council

Free at last, Archbishop Lefebvre wished to use his time usefully by studying modern languages, especially English. He was not allowed the leisure to do so. His status entitled him to receive an important diocese, and accordingly, His Holiness Pope John XXIII wished to appoint him to the Archdiocese of Albi, which, evidently raised an outcry among the French bishops! In 1962, he was, at last, named Bishop of the little diocese of Tulle, and, soon after, Assistant at the Pontifical Throne. In August 1962, L'Osservatore Romano announced that the Pope had honored him with the title of Archbishop of Synnada in Phrygia.

He became directly acquainted with the problems of the priesthood in France. While others wrote pretentious circulars on the "priest of tomorrow," he was thinking up practical solutions. He knew the terrible loneliness of the priest... this is why he suggested that priests should be settled in pairs, should have a small car at their disposal to travel about the countryside, and the chance to meet during the day.

|

|

In July 1962, the General Chapter of the Holy Ghost Fathers, the most important missionary body in the Church, met to elect a Superior General. The Rule of this body demands that, if the candidate is a bishop, he should receive two-thirds of the vote on the second ballot, a rare event. However, on this occasion, since many votes had been cast for him in the first ballot, Archbishop Lefebvre begged his brethren not to choose him and to leave him to his diocese of Tulle. This was of no avail, and, on the second ballot, he received the heavy cross of being Superior General for twelve years.

Six years later, in 1968, a new General Chapter was convoked. The hour of the aggiornamento had tolled for the Holy Ghost Fathers. His Grace has written:

It was certain that changes would be necessary, so the Superior General could be overthrown; not because I was Superior, but because the Superior had full powers. He was 'the boss.' This could not go on. Even before the Constitution was changed, they wanted a team of three to run the General Chapter. I said that it would be necessary to change the Constitution first, and asked for a vote on this issue. There was a small majority against me, saying that a team would be needed, from which, of course, I was excluded. I was not chosen for any commission. I was still the Superior for six years, until 1974... but I no longer counted for anything.

When Mgr. Moro, Cardinal Antoniutti's deputy at the Congregation for the Religious Orders, informed him that, in the same situation as himself, the Superior of the Redemptorists had been invited to go on a journey to the U.S.A., Archbishop Lefebvre's smile was a little broader than usual. For him, tourism did not solve any of the difficulties of religious orders! A few days later, his resignation was immediately accepted.

1962-68 was the most important and most devastating period of Vatican II, and the reforms which came from it. On this occasion, His Grace was called upon by Pope John XXIII to participate in the Preparatory Commission of the Council, to cooperate in drawing up the draft documents to be presented to the Council Fathers. According to what he has written and said, Archbishop Lefebvre went to the Council "full of illusions and full of hope." His dynamic character, his common sense, and his long experience in missionary work made him see the need for a true reform:

Indeed, reforms were necessary. As the Church Militant goes its way, the message can be blurred, the Church's enemies may choke the good seed, the negligence of priests may lessen Faith, Christendom may listen to the deceits of this wicked world (A Bishop Speaks, Vol. I, p. 76).

The Sacred College as a whole, and most of the curial cardinals, guarantors of such a renewal, supported the traditional wing, led by Cardinal Ottaviani. Only a few Roman prelates and the bishops from the Rhine countries, supported the progressive wing, led by Cardinal Bea. Taking advantage of the last moments of John XXIII, the latter maneuvered the election of Cardinal Montini, Paul VI.

His Eminence, Cardinal Browne, and the Archbishop at the heart of the celebration of the centenary of Rockwell, in Ireland—1964 |

During a session of the Central Commission, Archbishop Lefebvre publicly expressed his astonishment at the presence of distinctly dubious theologians in the subcommissions such as Küng, Rahner, Congar and Schillebeeckx. During an interval in the session, Cardinal Ottaviani explained to him that this was the wish of Pope John XXIII who was convinced that, surrounded as they were by competent persons of fervent faith, the opinions of these theologians would not deviate from Catholic orthodoxy at all. Some of the liberal periti realized that there was no hope of getting their views expressed explicitly in the Council texts, so they adopted another tactic. They then inserted ambiguous phrases into the conciliar texts which they could exploit after the Council, providing they would gain control of the post-conciliar commissions, which they eventually did (See The Rhine Flows into the Tiber, Fr. Wiltgen, p. 242).

The conservative tendency had a majority which seemed sufficient to allow a desirable development in discussion and voting, but the decisive and dedicated support of Pope Paul VI for the Liberals caused the conditions necessary for a truly Catholic reform to vanish. The conciliar documents contain ambiguities which result in an adulterous marriage of the Liberal view of Man and Society with traditional Catholic doctrine.

Behind the facade of the Council halls little meetings were held in the shadows—from the meetings of the French episcopate, where Congar would tell the bishops what interventions to read out, to secret decisions made in advance. Certainly, this is what Archbishop Lefebvre says, and he saw these meetings take place at the French Seminary. Jean Guitton bears witness to the same thing, when he puts into Cardinal Tisserant's mouth these words on a painting by his niece: "This is an historical, or rather, a symbolic painting. It depicts the meeting which we held before the opening of the Council, where we decided to obstruct the first session, by refusing the tyrannical rules set up by John XXIII" (J. Guitton, Paul VI's Secret, p. 123).

These reforms enacted in the name of the Council are not, then, an unjustified interpretation of it, for those who promulgated and who apply them are those who say: "We do this in the name of the Council, we created the liturgical reform in the name of the Council, we reformed the catechism in the name of the Council." They are in authority in the Church, and so it is they who legitimately interpret the Council. M. Prélot was to admit as much in the first few pages of his book, Le Catholicisime liberal, "For a century and a half we fought without success to have our view triumph within the Church. Then came Vatican II and at last we triumphed. Henceforth the ideas and principles of Liberal Catholicism are definitively and officially accepted by Holy Church." Archbishop Lefebvre was to comment on this matter during his homily at Lille on June 29, 1976: "Isn't that proof enough for you? It was not I who said that. But he said it in triumph, and we say it in tears..."

The Society of St. Pius X

"There is no greater treasure in Holy Church than a holy priest."

A working paper for the 1971 Synod of Bishops noted that many priests were going through an identity crisis. They were suffering from apathy and insecurity, and no longer understood their priestly role.

|

|

Since Vatican II there has been a decline in the educational standards of seminary professors, and of competence, of discipline and of piety among the seminarians. In short, standards have been lowered in every aspect of the training of priests. That could not but disturb zealous pastors, truly Catholic families and young aspirants to the priesthood.

Instinctively, those responsible for vocations, especially in France, considered how to find institutions likely to give proper training to their protégés. This is how certain anxious requests reached Archbishop Lefebvre, asking his advice on this subject as soon as he had settled in Paris, as Superior General of the Holy Ghost Fathers, in 1962.

Hoping to revive the sound traditions of the French Seminary in Rome, entrusted to his Order, he sent those with vocations to this institution. So, from 1964 onwards, a dozen traditionalist students were there together. Two years later, in 1966, this number had reached twenty, forming quite a powerful and influential group in the Seminary. They thought that through their hard work, they could influence the evolution of the Seminary, which is what Archbishop Lefebvre asked of them during the frequent meetings he had with them. On more than one occasion he went to the Seminary in person to advise them on the correct attitudes to take.

In the middle of the conciliar period, with some fifty bishops in residence, the agitation that they gave rise to and the daily conferences on the Council given by the "representatives" of the majority made a religious life and keeping a firm position difficult. The hope of more propitious days was completely ruined by the opposition of most of the seminarians and members of the teaching staff.

The time to take the tonsure came, after three years at the Seminary. Most of the members of the little group were refused. Persecution was beginning and, sick at heart, they had to look for a new home.

By 1968 the progressive spirit was in complete control at the French Seminary in Rome, and had swept away the structures which made it a true Seminary. At any rate, it was necessary to leave. The seminarians could not find a seminary in which to receive a good spiritual formation and had to fight continually against the atmosphere of decomposition prevalent everywhere.

So it went until Archbishop Lefebvre resigned as Superior General of the Holy Ghost Fathers.

The International Seminary of St. Pius X, located in the heart of the Swiss Alps, at Ecône, a place beloved by Roman Catholics from around the world |

Seeking to escape the unchained storm that had been unleashed by the aggiornamento, His Grace immediately set out to address this problem with Bishop Francois Charrière, Bishop of Lausanne, Geneva and Fribourg, whom he had recently received at Dakar. Very strongly encouraged by him, the Archbishop founded "An International House of St. Pius X," for priestly education on June 6, 1969, at Fribourg, Switzerland. So the seminary was born at 3:00 p.m. in a little office at the Bishop's residence. The seed was sown...

Many students gave up during the first year, in disagreement with Archbishop Lefebvre's position concerning the Council and its reforms. At the end of June, 1970, only four seminarians, assured that the Superior would not abandon them, went on holiday. The Superior's reply to the seminarian Cottard, still at the French Seminary, illustrates the difficulties of this period. To the request for permission to enter his new foundation, "because here the Red Flag flies over the seminary." The Archbishop answered: "You know things aren't going very well here and I don't know if we'll carry on." Divine Providence was testing the work it was to bless!

At the same time as he was assuring the future of his seminarians to the best of his ability, Archbishop Lefebvre had to cope with a constant and increasing stream of demands for candidature to the priesthood in the period after 1967.

|

"No authority can force us to abandon or diminish our Catholic Faith, clearly expressed and professed by the Church's Magisterium for fifteen centuries." Archbishop Lefebvre, |

As he wished his protégés to have access to Holy Orders, he consulted the Order of Knights of Our Lady, with the thought in mind of training priests under the aegis of Archbishop Michon, Protector of the Order.

The Grand Master's reply was slow to come, and negative, but he did suggest contacting the Knights of the Valais, who owned a building suitable for use as a seminary.

As he had already considered Fribourg, where he had sent several seminarians, and as he knew the two bishops of French-speaking Switzerland well (Bishop Charrière and Bishop Adam), Archbishop Lefebvre decided to go to the Valais to find out more.

|

|

The workings of Divine Providence can certainly be seen in the almost miraculous manner in which the Archbishop was able to obtain a large house which had belonged to the Canons of St. Bernard in the Diocese of Sion. The house was located in the almost unknown hamlet of Ecône, near Riddes. God's instrument in this case was the late Alphonse Pedroni, who told the Archbishop: "Ecône will soon be known throughout the world!" Mr. Pedroni was a true prophet.

It was through Father Bonvin, his former colleague at the French Seminary, that His Grace met the Canons of the Great St. Bernard, who had bought the house and estate of Ecône, where the famous dogs had once been trained, so "that it should not be used for an unworthy end."

At Easter 1970, after a year's reflection, and urged on by numerous requests, Archbishop Lefebvre asked the Canons whether it would be possible to hold first-year classes in the spiritual life there.

Despite many problems, the first year was to open at Ecône, in September 1970. However, Fribourg had not been abandoned, and during the summer His Grace decided to lodge the second year there on Vignettaz Street. In October classes began at Fribourg and Ecône, preceded by a retreat.

On November 1, the seminarians of Ecône took the soutane and the day ended with a good Valaisian party! But on Saturday, November 7, at Vignettaz Street, something important happened. This is how Father (now Bishop) Tissier de Mallerais, present at the scene, describes it:

Archbishop Lefebvre, with a mysterious smile, took a big envelope with a coat-of-arms upon it from his pocket, and, showing it to us, he announced, not hiding his delight, the official establishment of the "Society of St. Pius X" in the Diocese of Fribourg, by His Excellency Mgr. Charrière; the document was dated November 1, 1970.

We were overwhelmed with joy, the Archbishop more than any other! To see our wish fulfilled without any difficulty, at the stroke of a pen! We kept on passing the letter from hand to hand, reading the text, examining the signature and the seal; yet all was in good order. Our Mother, Holy Church, gave birth to us on that day, such as we are, and such as we shall, God willing, remain.

Miraculous appears to be the only term adequate to describe what happened next. The newly established seminary soon proved too small to accommodate the young men flocking there from all over the world. New accommodations and lecture rooms needed to be built immediately but the cost would be enormous. Word of what was taking place had now reached faithful Catholics in many countries, and the necessary donations began to arrive. As fast as new extensions could be constructed they were filled, and still more building had to be undertaken. More professors were needed, and such was the esteem in which the Vatican held the seminary that it authorized the transfer of priests from other orders to the Society. The esteem was further reflected in an enthusiastic letter from Cardinal Wright, Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Clergy, dated 18 February 1971, in which he praised "especially the wisdom of the rules which regulate and direct the body." The Cardinal assured Archbishop Lefebvre that bishops in different parts of the world approved and praised the seminary.

The Society Under Attack

Satan ensures that any work which is of God, and which is frustrating his designs, soon comes under attack. The Society of St. Pius X was no exception. Its success and its prestige were a standing reproach to most other seminaries, especially those in France which were closing down at an embarrassing rate. There had been an 83% decline in seminary enrollment in France since the Council, which hardly constituted an endorsement of the new style and methods which the French bishops had introduced in order to make seminary education "relevant and attractive" to young men in the closing decades of the twentieth century.

His Grace is shown here with his successor as Superior General of the Society of St. Pius X, Father Franz Schmidberger |

A campaign of innuendo and outright lies was launched to discredit the Archbishop, the Society and, above all, the Seminary at Ecône. It was described as a "wildcat seminary" which had never received official authorization. The same distorted reports began to appear in English-speaking Catholic papers, and are still appearing. These journals will rarely correct even the most blatant untruths when they receive protests from their readers. Archbishop Lefebvre is almost invariably described in the Catholic press as the "rebel bishop," when, in fact, his only offense is to refuse to rebel against the teachings and traditions of two millennia.

A Travesty of Justice

The Pope was put under considerable pressure to act against the Society, principally by Cardinal Villot, his French Secretary of State, who served as the mouthpiece for the bishops of his country. Some Catholics have a very naive idea of the papal office, and imagine that the Pope is free from human weaknesses. Even a cursory study of papal history will prove that this is not the case, and that there are few forms of human weakness to which at least some popes have not succumbed. A pope is as liable to surrender to pressure from powerful and influential lobbies within the Church as is the chief executive of any secular organization to similar pressure. History abounds with such instances, and injustice has often resulted when a Pope gave way.

Pope Paul VI was known in Italy as the "Hamlet Pope," such was his indecisiveness. He agreed that the Seminary should be subjected to an Apostolic Visitation. This is an inspection by representatives of the Vatican. The fact that this Visitation took place provides all the proof necessary that the Seminary at Ecône was canonically established. The Pope does not send Apostolic Visitors to "wildcat seminaries" established without his authority! The Visitation took place in November 1974, and it eventually transpired that the report was favorable, at least to the extent that the very thorough inspection and examination of professors and seminarians did not unearth a single justification for complaint, let alone closing the Seminary.

What happens next almost defies belief. It appears to be a page from the history of Stalinist Russia rather than an episode in the life of Holy Mother Church. What happened shall only be outlined in the briefest detail, and if those who are new to the story of the Archbishop refuse to believe what is written, they cannot be blamed. We can assure them that the whole process is documented in the fullest possible detail in Michael Davies' Apologia Pro Marcel Lefebvre. We ask them to have the fairness to at least examine the facts before dismissing this account as preposterous fiction.

Bishop for EternityWhen His Grace was asked what struck him most on learning that Pope Pius XII had chosen him to be a bishop, he expressed how, at that moment he felt with pain, the impression of being "separated from the other ones." "One is marked, one is noted by his habit, by his mitre, by his crozier, by his position in the diocese." From one living quietly with his confreres in the ordinary environment of the apostolate, he found himself suddenly torn away and separated from the commonwealth of mortals. He realized that he was dedicated for all time to be a leader. "It is necessary to recognize that that was a trying experience, but, in any case, this is what I felt in leaving for Dakar. I became conscious of the fact that I had a whole diocese in my care, so many souls for which to be responsible! Was I truly capable of bearing the responsibility for 220,000 souls? It is more terrible that one can imagine because he knows he will be this way until the end of his life." |

Archbishop Lefebvre was asked to go to Rome in February 1975, for a "discussion" with three cardinals. On the following May 6, he received a letter from the cardinals informing him that the "discussion" had, in fact, been a trial; and that it had brought to light what the Apostolic Visitors had not been able to discover (proving that their report had been favorable). The cardinals stated that they had been instructed, by an authority they did not name, to tell Archbishop Lefebvre that he had been found guilty, and that he must disband the Society of St. Pius X, and close down his Seminary. Thus, not only had he been deceived into believing that his "trial" was a discussion, but he was not even allowed to know who had pronounced the sentence against him!

The Archbishop protested that the whole procedure was a moral outrage, offending not simply all accepted canonical procedures, but every principle of natural justice. He was, of course, correct! It is hard to believe that a prelate with such a record of service to the Church, a former Apostolic Delegate and Superior General of the Church's leading missionary order, had been denied the elementary standards of justice which would be accorded to a common criminal in any civilized country. Even if any of the personal opinions which he had expressed merited censure, this would not have justified suppressing the Society of St. Pius X. To punish an entire religious order for an offense committed by its superior was unprecedented and outrageous, particularly when, as a close examination of the proceedings reveals, the Superior had committed no offense!

|

|

The Archbishop followed the correct canonical procedure and appealed, but he was denied even this right. Faced with a prima facie case of an abuse of power, he stated that he would not comply with the order unless he was accorded the proper canonical procedure. If this were granted he would agree to close his Seminary, if ordered to do so.

This right was not accorded to the Archbishop and so he refused to comply with the command to disband the Society of St. Pius X. This decision is of crucial importance in understanding Archbishop Lefebvre's attitude to subsequent measures taken against him. Individual Catholics must base their decision as to whether they can in conscience support the Archbishop on their reaction to his refusal to submit to an abuse of power. His Grace wrote of this time:

I was therefore expected immediately to dismiss from the seminary 104 seminarians, thirteen professors and other personnel. And this, two months before the end of the school year! One only requires to write this down in order to know the reactions of anyone who still retains a little common sense and honesty. And all this on 8 May in the Year of Reconciliation!

| When the history of the contemporary crisis of the Church comes to be written there is one name which will stand out above all the heroes of the Catholic Resistance, that of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. |

The Archbishop was forbidden to ordain any more priests, but he insisted upon doing so in June 1976, and was suspended in July of the same year. The suspension was to last for a year, but was extended automatically in June each year when he ordained again. He has ignored this suspension completely on the grounds that as his initial condemnation was, at the very least, a violation of natural justice he has the right to ignore it and that as all subsequent measures stemmed from this original condemnation, he has the right to ignore them.

His Grace in 1976 |

If the Vatican had hoped that suspending Archbishop Lefebvre would deprive him of the support he enjoyed among the ordinary faithful it miscalculated badly! Under the terms of his suspension he had been forbidden to offer Mass in public. In August 1976, he agreed to respond to an appeal by French Catholics to celebrate a Mass at Lille. They took the bold step of hiring the vast hall of the International Fair in that city. It had seats for 10,000, with room for several thousand more to stand. A congregation of less than three or four thousand would have been seen as a public humiliation for the Archbishop. Not only was every seat taken, and every inch of standing room filled, but hundreds of the faithful had to remain outside. This Mass set a pattern for subsequent events. In contrast with the accelerating decomposition of the official Church, the Society of St. Pius X has continued to expand, not simply steadily but spectacularly. Hardly a month passes without new churches being purchased somewhere in the world, convents founded and schools opened. Recent Vatican reports say that the Society of St. Pius X has 500,000 to 700,000 followers. Their estimate is low!

The story of Archbishop Lefebvre's defense of Tradition is chronicled in explicit detail in Michael Davies' Apologia Pro Marcel Lefebvre. Volume One covers the period from 1905 to 1976; Volume Two from 1976 to 1979; Volume III, which is forthcoming in the immediate future, chronicles the struggle from 1979 to 1982. Volume IV will appear later in 1988. Those readers who wish to follow the story of Archbishop Lefebvre, almost from month to month, will find these books fascinating and most enlightening.

* * *

The Lefebvre family were no strangers to crises, to suffering, and to apparently hopeless situations, but these were inevitably overcome with the help of their unflinching Faith. During the First World War they underwent the trauma of German occupation. Monsieur Lefebvre organized the escape of Allied prisoners from German-occupied territory. He later escaped to Paris and, under the name of LeFort, worked for the French Intelligence, undertaking the most dangerous of missions. All this became known to the Nazis, and when they occupied France in World War II, they arrested him as a potential leader of the Resistance. He was imprisoned at Sonnenburg, where he died after brutal treatment, an inspiration to his fellow prisoners.

While her husband was away serving his country during World War I, Madame Lefebvre directed the family business, looked after her children, cared for the wounded, visited the sick and the poor, and organized resistance against the Germans. She was imprisoned and became so gravely ill that her death appeared imminent. But she would make no concessions whatsoever in order to secure her own release. The German commandant begged her to write a note asking to be pardoned, but she refused to do so, preferring to die rather than compromise on a matter of principle. Fearing the consequences of her death, the Germans released her. She returned to her family broken in health, but unbroken in spirit.

With such parents, it is not hard to understand why the Archbishop is endowed with a character which enables him to refuse all compromise, no matter what the cost.

Most Catholics have remained passive in the face of the conciliar crisis. They may not have welcomed the liturgical, moral and doctrinal decadence which they see all around them, but they have not been willing to play an active part in combating it. This is hardly surprising when most of the clergy from whom they might have expected leadership never cease telling them that the degeneration which is taking place in every aspect of Catholic life is, in fact, an unprecedented renewal bringing incalculable benefits to Catholics everywhere.

Some Catholics have drunk the poison of Modernism with relish. Like so many heroin addicts, they believe they are undergoing an experience which is enriching their lives, not realizing that it is destroying them. Prophets of decadence, they urge us all to drink deep of the Modernist poison to which they are addicted, and share with them the hallucination that the Church did not really begin until Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council.

Other Catholics refuse to abandon the Faith which they have received. They see it as a sacred trust which is their duty to preserve and hand on undiminished. When the history of the contemporary crisis of the Church comes to be written there is one name which will stand out above all the heroes of the Catholic Resistance, that of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre.

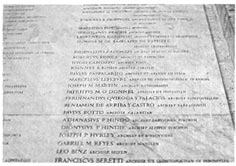

A photograph of one of the marble plaques situated at the entrance of St. Peter's in Rome, on which are the names of the Bishops who participated in the proclamation of the dogma of the Assumption.