CARDINAL PIE'S DECLARATION OF DEPENDENCE

The "Four Gallican Articles of 1682" marked a chapter in the struggle between the papacy and Catholic nobility about which was superior. In the quarrel between King Louis XIV and Pope Innocent XI, Louis had an assembly of bishops pass the "Four Gallican Articles of 1682," providing that kings were not subject to the pope, that general councils superseded the pope, that the pope must respect local custom, and that papal decrees did not bind unless accepted by the whole Church.

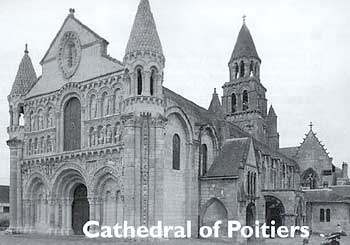

In response to a letter of his defending the prerogatives of the Catholic Church, Cardinal Pie (d. 1880), Bishop of Poitiers, France, received a declaration of abuse from M. Suin, the French Minister of Public Instruction and Cults, which invoked the first article of the "Four Gallican Articles of 1682" against the Cardinal. The Cardinal's response, published here for the first time in English, goes beyond a mere refutation of M. Suin. Cardinal Pie began:

The first preamble of the Decree of the Counsel of State is formulated thus:

Whereas in the terms of the Declaration of 1682, it is a fundamental maxim in French public law, that the head of the Church and the Church itself have received power only in spiritual matters, and not in temporal or civil matters, and that, consequently, the pastoral letters that the Bishops can address to the faithful of their dioceses must have for their aim only to instruct them on their religious duty [emphasis added–Ed.].

M. Suin's report...says that the bishops have a right to teach the texts of our sacred history, the truths of our dogma, the sublime morals of the Gospels, the necessities of prayer, the consolations of faith, the exhortations to charity, the hopes or the fears of a future life: not to the people, who are confided to the sovereign, but to the faithful of his diocese, which is much different.

I understand. In the name of the State, M. Suin has certainly wanted to determine for me the substance of my instructions and to designate for me the portion of the ground on which it is permitted me to establish myself. There is true and false in the program. What is false, I resist. What is true, I knew beforehand, and I held it from a higher source. I am not constrained within the limits that some have thought fit to set for me that I might not be able to move beyond these limits as far as the need of my cause requires.

It is admitted that the Church remains faithful to its prerogatives when it exercises its power within the bounds of spiritual matters, and when the bishops use their pastoral publications only to teach religious duty. The whole question consists in knowing where the domain of spiritual things stops, and where the sphere of religious duty ends.

Surely, no one will deny that faith and morality have a spiritual and religious character. But would one dare say that Catholics, under the double connection of belief and of duty, would never have anything to learn from the Church regarding theories or facts relating to the temporal and political orders?

The priesthood has received the divine mission to teach religious duty. This is acknowledged and that is sufficient for me. Let me be specific, however, and not drift from the present situation. In union with all the priests under me, I boldly announce the following facts. It is religious duty to adhere to the truth concerning the most vital questions of religion and of the Church. It is religious duty to know that antagonism does not exist between the principles of the supernatural order and the elements of true social progress. It is religious duty not to profess nor even think that the Gospel, the guide of souls into Paradise, must be eliminated from laws which govern the present interests of humanity. It is religious duty not to affirm that a government whose politics takes account of Catholic dogma is bad for that reason alone, bad not only in fact, but bad by essence. It is religious duty not to believe and not to say that there is another Gospel than the one which is preached by pastors in communion with the Supreme Pontiff, and another Gospel more pure and more primitive which governments or individuals can interpret to the point of opposing bishops and the pope and of giving themselves the mission of restoring the bishops and the pope to it. It is religious duty not to maintain that ecclesiastic sovereignty is condemned by evangelical law and that being pontiff prevents being king. It is a religious duty to believe in justice, in legitimacy, in the inviolability of what has been consecrated by time, by law, by religion. Finally, it is a religious duty not to insult the Spouse of Jesus Christ, to calumniate the Mistress and Teacher of Catholic societies, to accuse the Church of having compelled nations to subject themselves to her law or of having nourished them with her spirit in false and evil ways, to maintain that all the good of modern peoples proceeds from a movement which has been brought about outside of the Church and against the Church. What else can I say? There is not one of the rationalist axioms with which the enthusiasts of the new law arm themselves that is not more or less the denial of the perennial teaching of the Church, of natural wisdom itself, and of the tradition of mankind.

It is the duty of priests to refute these anti-Catholic and anti-social maxims. They must attack the theorists who put poison into souls with their lies. Even more so, they must combat the maneuvers of those who take aim to positively establish lies among accomplished facts. To hold one's tongue in such a case would be failure to protect the deposit of the Faith and to preserve the flock. It would be to abandon the teaching of religious duty. It would be to dismiss the power received from God over spiritual things. This would be a betrayal of truth, the Faith, justice, and everything that constitutes the Catholic and moral orders on earth.

I swear to you, Mr. Minister, when posterity will review this pastoral teaching of mine that is charged with notoriously infringing upon the temporal and civil domains, it will not discover in it one syllable which did not have an immediate and direct connection to spiritual and religious questions. When I examine all my episcopal publications of the past years, I do not find in any of them one word or intention which is not justified by a need of the times. There is not one instruction which does not have for its purpose the refutation of a pernicious error in order to ward off religious and social disaster.

The honorable M. Suin stops me at this last sentence and attempts to catch me in my words. "The Church," he will say, "acknowledges therefore its intention to intervene in social questions. What then about the first and the most uncontested of the Articles of 1682 denying it power to do so?"

I firstly respond that the Declaration of 1682 is not an act emanating from the Church nor ratified by the Church, and that, if the doctrine contained in the first article of this declaration is interpreted by lawyers and statesmen in a sense absolutely inadmissible to me because it would qualify as idolatrous, I will have no problem saying of this article what Bossuet said of the Declaration itself: Abeat quo libuerit–Let it find a welcome where it can.

Secondly, I respond that it is incontestable that social questions, because they are always tied to the divine and moral law, revealed or even natural, will never be able to be placed absolutely outside the Catholic Church's purview. I would be hairsplitting and lacking respect toward myself as toward M. Suin if I were to point out the extraordinary stupidity which brings him to refuse me any right of teaching over the peoples, to concentrate it only on the faithful. If the honorable member of the council wants to have his irritability triumph, he is far from the end of his difficulties. He will have to delete a great part of the Old and New Testaments. He will have to tear up all those chapters of the prophets which announce the reign of God on earth, by means of the incorporation of nations, of peoples, and of kings to the Jerusalem of Christ which is His Church. Above all, he will have to publish an edict pronouncing the abuse and decreeing the suppression of the divine formula of our investiture, "Go and teach all nations."

...I prefer to state the truth completely, and to repeat boldly that the duties of the citizen assuredly within the jurisdiction of the conscience are dependent for this right on a divinely constituted supreme authority which regulates consciences. The Church will not absorb, however, the power of the State. It will not violate the independence which it enjoys in the civil and temporal order. On the contrary, the Church will intervene only to have the State's authority and its legitimate rights triumph more efficaciously. I have never said that the Church, because it is its duty to enlighten consciences on the extent, meaning, and applications of the Fourth Commandment, must monopolize the divine and natural authority of parents over their children! Priests have the mission to explain paternal right and filial duty, yet the authority of the father subsists in its order. The commands of the father to his son draw their authority in no way from the clergy but from the very right of fatherhood.

It is the same way with the prerogatives of the Church regarding obligations of citizens and duties of public life. The Catholic Church does not claim to substitute itself for the governments on earth which the Church regards as ordained by God and necessary to the world. Against anarchical doctrines and revolutionary passions, it safeguards everywhere and always the principle of authority which is essential to the tranquility of the world and to the preservation of order. The Church teaches that the presumption of abuse must be rejected and that as a general rule obedience is the first and foremost duty. For its part, the Church does not interfere thoughtlessly and at every turn in the examination of the internal questions of the public government any more than it interferes in matters of how a father runs his household. Its role has nothing of the indiscreet nor of the odious. It is never untimely nor pestering. The most serious matters of legislation, commerce, finances, administration, and diplomacy are treated and resolved almost always under the eyes of the Church without the Church articulating the least remark. And, since I have in mind the Declaration of 1682, surely the first article of this declaration seeks a broad application. Yes, may the Church judge from the highest ground everything that concerns natural things, the civil, political, social, and international obligations and relations. Let the Church leave to secondary teachers the care of directly teaching these questions. Let it acknowledge to the purely temporal powers the burden of formulating them by laws and of protecting them by agencies. It is just; it is simple; it is the Church's mindset everywhere. Even in the Pontifical States, there remain lines of distinction between the spiritual and temporal orders. The spiritual order preserves for the temporal order all the freedom to move in its own and specific sphere. But to outlaw the Church of Jesus Christ from the right and duty to judge in the last resort of the morality of the actions of some moral agent, individual or collective, father, master, magistrate, legislator, even king or emperor, is to desire that the Church deny itself, abdicate its essence, tear to pieces its deed of origin and the claims of its history, and insult and disfigure the One whose place it holds on earth.

Moreover, the Church cannot reverse its opinion. It has always affirmed its right, and it has not ceased to exercise its right since the conversion of the pagan world. "Everyone is subject to its keys," Bossuet said, "everyone, my Brethren, kings and peoples, pastors and flocks. We proclaim it with joy because we love unity, and we glory in our obedience."1

As a matter of fact, kings, as well as the people, find advantages and guarantees in this. The dignity and the strength of a power are in direct proportion to how strongly it subordinates itself to truth and to justice. In proclaiming oneself submissive to God, one does nor debase oneself nor grow weak. "By me kings reign," says Scripture, "and lawgivers decree just things."2 But God having become incarnate in Christ, and Christ continuing to live, teach, and act in His Church, everything that depends on God in the superior order of spiritual, religious, and moral things, depends consequently on Jesus Christ and His Church.

Perhaps, next to the innumerable undertakings of the secular power against the Church, some cases of encroachment by the ministers of the Church against the temporal power could be alleged, but the right of the Church is not invalidated by the excess of some of its own, and the Church itself has tribunals, laws, and means of repression to use against them, when the Church is permitted to avail itself of them.

[Cardinal Pie applies these principles to the particular events of France's long and storied history, and points out that when monarchs rebel against the Church's authority, then their sword is weakest and their reign troubled.–Ed.]...

We know that no one will be discouraged from attempting the experiment. Free from care, the jurists, the politicians, all the evil genies of power, will imperturbably revive the same formulas...and the Church will continue to witness the same spectacles. Neither her patience nor courage will tire. She is also resigned to see up to the end the sad scandals of popular, social, legal, and imperial revolts. She is assured of crossing the ineffectual barriers that one opposes to her, and of witnessing sooner or later the chastisement of the rebels who will have raised them.

What does one expect from a State out of control, where the actions of the prince or of the sovereign people [i.e., democracies, where it is held that authority is derived from the people themselves and not from God–Ed.] escape the very authority of religion? It is force substituted for law. It is the will identified with reason. It is politics returning to paganism and infidelity. It is Christ excommunicated from human society, or better, it is the State made God. Yet, in fact, the deification of a created being is infallibly ruin and death. One may call to mind Nebuchadnezzar, Antiochus, Herod Agrippa, and so many others. Profane history itself shows us human apotheosis only among the tragic pomp of funeral ceremonies.

Finally, a great deal of reflection is not necessary to see that this so-called independence of sovereigns, deadly to their power and sometimes to their person, is no less fatal to the people whom they govern. The people, it is true, know how to resist these independent guides to whom they are confided. And can the princes really say what is better for them: control by the Church, a supernatural power, and by the admission of everyone an important, moderated, tested power, or control by this blind, passionate, inconsistent force, that is named opinion and the popular will? Nevertheless, I acknowledge, it is always, in the last resort, the people who are victims. If despotism brings rebellion, rebellion brings corruption of morals as well as of spirit. And nations, tossed about by revolutions without end, oscillate between anarchy with its ruins, and dictatorship with its rigors and its infamies. Such are the inevitable fruits that princes and the people harvest from their absolute independence from the Catholic Church.

Translated exclusively for Angelas Press by Mr. and Mrs. William Platz from Œuvres Sacerdotales du Cardinal Pie, Choix de Sermons et d'Instructions de 1839 à 1849 ["Third Synodal Instruction" (V, 135-140)]. The couple responded to an invitation in The Angelus for translators to make the work of Cardinal Pie, a mentor for Pope Pius X and Archbishop Lefebvre, available in English, for most of it is only known in French. Heavily edited and adapted by Fr. Kenneth Novak.