THE HEART OF ST. JOHN BOSCO

This conference is going to look at the method of formation for children of St. John Bosco. Fr. Fullerton could be doing it himself because it's the method he implemented at our St. Joseph's Boys' Academy [Richmond, Michigan] for the six years he was the principal there. He thought it was important at this Principals' Convention we see St. John Bosco as an inheritor of the Church's wisdom regarding education, which he perfected in its practice, and crystallized in a method approved by the Church and handed down to us. My talk will be mainly theoretical yet adapted from my experience of teaching the past three years in our boys' school. At the outset, I want you to know that whatever I say to you I say to myself.

To understand the "method" of St. John Bosco is to understand this Saint of the Church. His first principle of education is to conquer the heart of the students. That was the wisdom of the ancients–Plato, St. Augustine, St. Anselm, etc. As we know in our teaching apostolates, if you want to have an effect on someone, you firstly have to win that person. Obviously the means of doing this have to be regulated by virtue and prudence. But the heart must be conquered, especially of children. This is the essential end of John Bosco's "system." Therefore, to understand the heart of this man is to understand his system. It's really to get a glimpse into the heart of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Now, many saints may have had opinions about education, but St. John Bosco's sanctity was built upon his particular vocation as an educator of children by means of a system permeated by the charity of Our Lord Jesus Christ. It is important we don't separate the saint from his method.

We have to continuously remind ourselves of the objective which needs to be obtained. What are we shooting for here? It's the formation of the Christian man. In his great encyclical On Christian Education [Divini Illius Magistri], Pope Pius XI wrote:

[T]he proper and immediate end of Christian education is to cooperate with divine grace in forming the true and perfect Christian....Christian education takes in the whole aggregate of human life: physical, spiritual, intellectual, and moral, individual, domestic and social, not with a view in reducing those in any way, but in order to elevate, regulate and perfect them in accordance with the example and teaching of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

So the aim of education is the perfect Christian; its scope, the whole man. The modern idea of education is to only give certain facts about any given discipline, but the purpose of Catholic education is to form and perfect the whole man in the life of Our Lord Jesus Christ. To know our aim and scope determines the means we will employ to obtain them.

Among the spectrum of methods used in the history of education there are two general categories–the repressive method and the preventive method. Now, to properly understand St. John Bosco and his way–this conquest of the heart–we have to have the idea of these two methods in mind.

What characterizes the repressive method is making known the law and stern warnings regarding its transgressions. Once the law has been made known, its keeping will be based on the fear of those under the leaders, not wishing to transgress. Why? because the person in charge is going to watch and wait for transgressions to happen. Fr. Auffray, a biographer of St. John Bosco summarized the repressive system this way: "The repressive system keeps the superior at a distance in splendid isolation...." That is to say, if I may characterize, there's the superior, going about his own things, doing his own things, and every once and a while he pops in, "smacks a kid on the hands," then pops back into his "splendid isolation," concerned really only about himself most of the time. Fr. Auffray continues, "...which [splendid isolation] he leaves only to show severity and this provides the well-known parallel lines along which masters and boys move without ever any risk of meeting." That's the repressive system. The repressive superiors characteristically think, "Let's not get too close to them. Let's not have any real contact with them because we're the superiors, we're the ones in charge. Just make the subjects obey." It tends to be severe, detached, no friendliness, no familiarity; you're cordial, you're cold; everybody keeps within their own spheres. Simple material obedience. St. John Bosco would ask, "What kind of real effect are you going to have on children that way?!" Are we looking for the heart of a child in this method? What's "nice and military" may work in the military, but even there the best military leaders have won the heart of their soldiers by something other than the repressive system strictly speaking. Is this education? "Listen, here are the rules. Keep the rules. Make sure your tax forms are in by April 15. See you at the end of the year. There are the rules." It might work for those who are older and more judicious coming into the system, but it doesn't work with the young. In the experience of the Church, of the saints, and by our own experience, it just doesn't work. What does?...

The preventive method is based on the axiom that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It makes the rules known and sees they are kept, but instead of obedience based on fear, it sees to rule-keeping based on charity, that is, by an accompaniment which is constant, careful, judicious, reasonable, and religious. This accompaniment, this assistance, allows the subject to best fulfill the rules of the institute. It's based upon a relationship of charity akin to the relationship of a father to his children. St. John Bosco left no great wealth of writing: what he left was a life he had lived and this relationship comes up repeatedly with him. One of the earliest and best of his biographers, Fr. Bonnetti, a Salesian who spent 30 years with Don Bosco, gives us an idea of the preventive method put into practice. Don Bosco was a man living the life of Christ before his boys, a man living the life of Christ and applying that to education. This takes great amounts of time and energy–a selfless, Christ-like, constant service and devotion.

The objections to the method of St. John Bosco are easily answered by the fact that the Catholic Church has said that the statutes and regulations of the Salesian Order, approved by Blessed Pius IX (1854), are good and can be used in full liberty. Obviously, we are not meant to become Salesians, but the method of the Salesians has had great results in 130 countries throughout the world. This proves there is something perennial in the method of Bosco which is based on factors outside shifting disciplines and changes of time and place. And what is perennial is useful in our schools. If we criticize the method of St. John Bosco, we criticize the Church's approval of him. The only valid criticism of the method of St. John Bosco is not a criticism of his method per se, but a criticism of someone improperly applying it. That, however, is not a reflection upon the method but upon the one improperly implementing it, who misunderstands it, or who is defying circumstances that make it untenable in a special situation. In any case, we're imprudent to criticize anything before we know what or who we're criticizing.

The spirit–the heart–of St. John Bosco's method is that of Christ, of the Church, and for that, it depends on leadership. Because these are conferences for principals, these are leadership conferences. We are Christian leaders and have to lead properly. And, we're leading children; we're leading young men and women and a teaching staff besides. Our understanding of leadership and authority must not be simply some theoretical concepts, but how we concretely and prudently apply these concepts in our particular apostolate as a school principal.

To understand the preventive method of St. John Bosco, that is, the conquest of the heart, I begin with a quote from St. John Bosco himself:

Reason and religion are the two springs of my method of education. An educator should realize that all these lads, or nearly all, are smart enough to sense the good done to them and are innately open to sentiments of gratitude. With God's help, we must strive to make them grasp the main tenets of our faith, which, based entirely upon charity, reminds us of God's infinite love for mankind. We must seek to strike in their hearts a chord of gratitude, which we owe God in return for the benefits He so generously showers upon us. We must do our best to convince these boys through simple reasoning that gratitude to God means, concretely, carrying out His will and obeying His commandments, especially those which stress observance of the duties of our state of life. Believe me, if our efforts succeed, we have accomplished the greater part of our educational task.

That is, lead the children to realize they need to be grateful to God, not just some pie-in-the-sky gratitude, but concretely. What does gratitude to God mean? Keeping the Commandments and doing your duty with charity. You've now conquered. That's the major task of education. St. John Bosco says the secret of his method of education is summed up in two words: "Religion" and "Reason": religion genuine and sincere to control one's actions and reason to apply moral principles to one's activities rightly. This is an introduction to the method of St. John Bosco. We'll look first at reason.

REASON

When St. John Bosco talks about reason, he is speaking about the use of reason. It's the first, it's the most natural principle of any human undertaking. To act according to right reason; that's specifically human. In any endeavor or domain humans must strive to always act with right reason. St. John Bosco helps us discover how to use our reason–that is, what is reasonable–regarding the education of children.

He says no genuine education can be imparted without constant use of reason, that is, good common sense. More specifically, St. John Bosco applies the charity of Our Lord and the Church's wisdom to say that the educator acts reasonably when he is a man of virtue. That's reasonable. It's not easy for a man to be virtuous, but it is reasonable for him to be so. Yes, Don Bosco spent a lot of effort on the children, but he was extremely rigorous, even severe, instructing his leaders–priests, brothers, and teachers–to be virtuous. Don Bosco didn't play games with those working with him. If you put yourself in front of his children to be a sign for them, you'd better be sure you're striving to be a saint.

Because it is reasonable for a man to be virtuous, it is also reasonable to fight against our passions. Each of us put in front of a class has his own temperament with its weaknesses and strengths. Passions have to be fought. The worst can come out of us when disciplining a child. Why? To take someone's head off at a given time satisfies our own anger. Control of the passions requires the engagement of the whole spiritual life–charity, patience, humility, temperance, etc. The rigor of the Catholic spiritual life is the measure of the rigor of St. John Bosco's method.

St. John Bosco says it is capital to be constantly vigilant that we are practicing charity in our own souls. Whether we do it or not is something that we have to work out, but we know what we have to do. That vigilance must also be toward the children. It is not to smother them; it is not a spy ring. It is an "assistance." Think of the image of an assistant priest at a first solemn high Mass. The new priest is a bit shaky and you've got that assistant priest there to give him the assistance he needs. This is a very good image of the educator assisting the children to do what they have to do. An assistant, especially one called to the vocation of educating children, cannot be someone who is detached, off in his office doing his own thing, finding his own things to do, satisfying his own whims and urges. For a principal, a headmaster over an entire school, the self must go. Our time is not our own time anymore, especially, I can say, in a boarding school. The 3:30 p.m. bell is not quitting time. More things must be done with the children to more deeply impress charity upon them.

Build a rapport with the children. Authority figures must avoid complications, says St. John Bosco, that is, let us say, constant new rules, constant typing up of signs and hanging them up everywhere....Authority figures are not loved when they become fanatical sign-makers to their authority, stamping their authority on every single place they go. That complicates things for children. Be clear and fair in the basic lines of the rules.

Think of where the Apostles came from. Let's keep our own personalities and our own social circumstances and perfect them in Our Lord Jesus Christ. It's not becoming someone else: It's perfecting what we are. Avoid artificialities, exaggerations, and formalisms. Children don't like that: they are repulsed by that. They like simplicity because they are simple. Become simple as the little children.

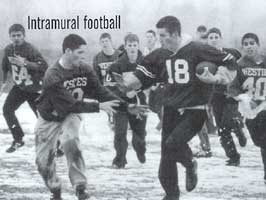

Don Bosco says, "It is reasonable to create in your school a family atmosphere." Now, who among us hasn't been hard on families, how dads aren't doing this and moms are doing that? As priests go, we are fathers* and our teachers "family oriented." We've got to create a "family atmosphere" in our schools. Children need it now more than ever. If they're not getting it at home, even more so we have to provide it in the school atmosphere. (Look how Our Lord dealt with the Apostles.) Remember, these children are co-heirs of the kingdom. We're all on the same team, all running the same race. Very often a coach in some sport can have the most influence in a young life. Without a doubt, I can say the defensive line coach at my high school has affected more children in my school than all the teachers combined. To every single kid who has ever played football at that school, he is the main guy in their lives. Twenty years later they still tell stories about him. For the best results, Don Bosco says, create this kind of family environment.

Don Bosco reminds us that Jesus Christ first did, then taught. That's a key principle when we're trying to pass something on to children–we have to do it ourselves. It's their homework, of course, not ours, but we must be virtuous ourselves before we tell the children to be so. This vigilance is going to be constant. This supervision is going to entail friendliness and familiarity.

Discipline is reasonable and therefore, according to St. John Bosco, there must be discipline. That Don Bosco appeared to be undisciplined is the biggest misconception people have of him. Let's face it, we priests might know a Breviary snippet of his life and most people have a St. Paul Media video-version in their heads. If I asked someone to write two lines about St. John Bosco, they would include something about hundreds of boys yelling, disarray, noise, a ball field with balls flying everywhere, a gentle priest with a biretta–that's Don Bosco. No! There's more to the Saint and his method, and more to daily school life. Just like in our schools, there is a bell that goes off in the morning, Mass needs to be attended, and duties have to be performed. Time has to be kept, you have to have orderly conduct, etc. All these things are necessary. There is serious discipline. For St. John Bosco's method to work, it cannot allow weaknesses of discipline and order or over-emotionalism on the part of the teacher trying to apply it.

The Saint says, "There must be a constant use of judicious discipline." That's St. John Bosco speaking, and that's not running haywire in the fields. Discipline plays a vital role in Don Bosco's educational system. One of his biographers says about him:

His idea was to persuade the boys to want to be good. Hence, Don Bosco was not greatly put out by the faults of levity proper to youth, nor to the inconstancy which is inherent in their state. Neither was he dismayed by noise or high spirits.

Persuade the children that discipline is for their benefit–that it's noble, just, and right for them to be good–and they will want to be good. Because it's the only true discipline, he wanted discipline to come from within and not from without. If it's just exterior discipline, it means nothing except hypocrisy. Children do stupid things, yes, but remember that we are leaders of children. Our apostolate is to accompany them, to assist them to get to Our Lord Jesus Christ. Precisely because of their immaturity, they're going to make little mistakes, faults, slips of the tongue, and absentmindedness. If you're dealing with children, be prepared for some loudness, some running and clomping in the hallways... It's not always a question of not having discipline, it's a question of just understanding that's what children do.

The school must require obedience properly regulated within the context of the rules. In practice this means obedience to all the rules, regulations, traditions of the institute. St. John Bosco writes, "By discipline, I understand a way of conducting one's self which is in conformity to the rules and customs of the institute." The rules and the customs of the school have to be obeyed. That's discipline. To obtain the best results from discipline, it is first of all necessary that the rules are obeyed by all, that is, all the children and all the staff. Don Bosco says, "The observance must be found first among the members of the congregation as well as the boys who are entrusted to their care." Imagine the scenario: You tell a child he has a test on Friday during second period, to make sure he studies, to make sure he's there on time. Then, on the day of the test, you walk in ten minutes late or don't correct his test for three weeks. You get the idea! We can only demand discipline when we are the first examples of it.

Don Bosco's discipline is based upon the genuine respect that is the hallmark of family discipline. In a superior, it is based upon the respect he has for the child as a baptized Catholic marked by the blood of Christ. In like manner, a child respects his superior, loving him for his virtue and sacrifice on his behalf. There was great respect for the Salesian superiors during the lifetime of St. John Bosco. And there must be respect–a spirit and love–for the school. This is not guaranteed just because a school has all the latest amenities; most of our schools are materially impoverished and it would be nice if they were better equipped, but to be so is not essential to respecting the school. We should find ourselves still thinking about our alma mater once in a while. A respect for the school goes beyond the child simply picking up litter–that will take care of itself if the child is imbued with the idea that his school is the best Catholic school in the United States, the only really Catholic school in his state, and that he's getting the best formation available. Principals have to set the tone; they have to believe it, too, and make the faculty and those associated with the school believe it. If teachers walk around grumbling, "This place is a dump," the children pick up on it.

St. John Bosco demanded obedience to rules and customs. He was hardest on his superiors. He knew obedience came easier to a child who had confidence in his superior's obedience. In a family that's running on all cylinders, there is confidence shared between the parents and from their children toward them. In a school, it must be the same way. It is very clear; it is necessary that educators build the child's confidence in themselves. When you've got that, then the child begins to open himself to being directed by you to Our Lord Jesus Christ. It's a self-surrender that leads to self-discipline to self-dedication to superiors, school, and ultimately the Catholic Faith and life, which is the most important thing.

This relationship of confidence which makes obedience easier is permeated with charity. The child sees the superiors as something near parental. A key point for St. John Bosco, however, is that the educator never relinquishes his power to punish though he may never need to use it or only rarely so. He gives the example of his mother. In the corner of one of the rooms in the house, she kept a huge stick. It was always there, a physical manifestation of the punitive power of the one who was in charge, yet he doesn't remember it ever being taken up. Obedience coming from confidence does not necessarily mean relinquishing our ability to punish, but if we are acting reasonably according to the spirit of the Church and Our Lord Jesus Christ as did St. John Bosco, its need is diminished.

Giovanni LeMoyne, another of Don Bosco's great biographers, wrote:

Discipline was no problem with John Bosco, or in his schools because duties were carried out with love; study and work were enjoyable because they were prompted by a sense of duty and honor.

Children love to do what it takes to get what they love. It's like Lent. Lent comes; we have to do penance. We don't love the penance itself but we love what that penance does for us, which actually makes it lovable to us. It's the same thing here. Duties are carried out for love of duty and honor. Children must be saturated with this idea. They become disciplined because they understood the need to be so and want to be so. It's nothing more than the spiritual life being applied to education. The quote of St. Augustine is applicable, "Where there is love, there is no labor." No matter how difficult the task is, when it's done truly out of love, the labor is willingly and easily undertaken.

Again, it starts with the superiors, with the teachers. St. John Bosco was very strict on this. He says if class starts at 8 a.m., be there at 8 a.m.; Rosary at 5:30 p.m., be there at 5:30 p.m. Our fidelity to our duties toward the children will be proportional to our fidelity to our own statutes and spiritual duties. Are we wandering in four minutes late to Rosary, making a sloppy genuflection, and sliding into the pew while the children watch us? We must feel a certain and constant pressure when we're in front of the children to be an example. We won't make a sloppy genuflection because they're watching us. We won't make a sloppy sign of the cross because how can we then tell them, "Listen, your signs of the cross look like you're brushing dirt off your chest." How can we say that if we're not doing it ourselves?

He was very hard on his men. Don Bosco says a leader is not supposed to push; a leader is supposed to pull. A leader is in front with everyone tied to him, pulling them to the goal. He's not someone in the back just leaning his weight against people. St. Augustine said it, "Almighty God was not content to tell us how to get to heaven, but He became incarnate in order to show us how to get there." Our leadership is by pulling, not simply by pushing. We must meditate on that. We are called upon to be Christ incarnate–concrete!–in front of these children. It makes education something incarnational. Important people came from all over to see what was going on at St. John Bosco's oratories. What did they see?–order, discipline, obedience, diligence, cheerfulness, and charity.

St. John Bosco says, "If a disciplinarian is charitable, he can be as firm as he wants." If he is truly motivated by charity and applies that charity to those children, he can be as firm as he wants because they'll accept it. They'll willingly accept his correction, even expulsion. In charity, if someone is damaging the common good, someone who insists on being a bad apple and upsetting the whole apple cart, he must be expelled (charitably!).

He talks about the need for leaders of schools to be strong. He said there is nothing that causes more lack of discipline in a school than a weak leader. And what is a weak leader? Someone who is not doing what he's supposed to do. It is the lack of virtue in the leader which is the major cause for lack of discipline in the school. When things are going crazy, when discipline is up for grabs, it isn't more yelling at the children that is necessary. No, we need to look in the mirror and see what's not going right in our own undisciplined spiritual and religious life, correct it, and then apply that to the children. That's what St. John Bosco did and that's why he was so hard on those he appointed to lead. The method of St. John Bosco is built upon the shoulders of the leader.

Another point which is indicative of the renowned discipline in Salesian schools was the personal cleanliness, modesty, and mannerliness of his children, though they came from poor families in bad neighborhoods. St. John Bosco said that a proper education is not complete without the attainment of social graces, the flower of charity. We're not talking about being prissy, we're talking about the manly manners of no one less than Jesus Christ–in the church, classroom, study hall, auditorium, ball field, wherever. Once a week in all his schools, St. John Bosco included an instruction on the proper social deportment for Catholic gentlemen. Our children must conduct themselves properly because they are representatives of the Catholic Church, of their family, of your school. He kicked this class off by composing a three-act skit to show what he meant by proper comportment. You can imagine what he did, showing some crazy guy not able to do his thing, spilling stuff on the ground, whatever, all the kids laughing. He got his point across in a cheerful way, an enjoyable way, but a memorable way.

St. John Bosco strove to arouse enthusiasm in the children for their Faith, work, and school by being a loving teacher. As St. Thomas Aquinas said, the best teacher will be the one who has two loves: truth and charity. He really loves what he teaches and really loves who he is teaching. Don Bosco perfectly applied this. If either is missing, we're not the magister, we're not a teacher. If we don't love what we're doing and we don't really want to transmit our knowledge to others, then we need to do some serious soul-searching to help ourselves out.

RELIGION

All that has been said so far regarding Reason leads us necessarily to Religion. If reason is not imbued with the Catholic Faith, it means nothing. St. John Bosco says the preventive system is based upon the precepts of the Catholic Faith. You can't have Bosco's preventive method without the Catholic Faith because it's reason and religion that are required and that necessitates the true Religion based upon charity. The Catholic Church offers the goal, and the guidelines and means to attain it. The preventive method must do the same thing. Here's the goal: Our education will form the perfect Christian. When we send this young adult into the world, he'll be an apostle, another Christ, with his Confirmation fructifying so he can defend and propagate the Faith. Then we have to give the proper means to attain that goal and that's going to be the Catholic Faith.

The first aspect of religion in education is to teach the children piety and prayer. For St. John Bosco, the child's life of piety and prayer is a manifestation of what is believed by him based upon his religious instruction. This is exactly what Pope St. Pius X would say a half-century later. Piety is not flowery devotions; it's based upon the knowledge of the Catholic Faith. "Piety with doctrine; doctrine with piety." Without those two working together, neither works. We're not wanting mechanistic piety, but true piety built upon strong conviction.

The measure of piety is how well our duties are done, willingly done. When your school children are making voluntary visits to the Blessed Sacrament, even if they be 30 seconds long, before class or a game, you're on to something. Outside the confessional, we should drop implicit, informal direction, "Hey, did you make a visit to the Blessed Sacrament today?" These things should be mentioned. Are we always talking about who's winning what games, scores, current events, and things like that? They have their place; they are even an important part of our apostolate to the children because we can show an interest in the things they think are important. This breaks the ice with them. But at the same time, if it's the whole conversation and we never mention the Blessed Sacrament, for instance, there's an imbalance in our approach. St. John Bosco anticipated St. Pius X when he said that instruction in genuine piety is centered on the Holy Eucharist. If that is true, we have to examine our own Eucharistic piety. What kind of visits do we make? When did we last read a book on the Mass? Are we digging to the very center of the entire life of the Church, of our own personal lives, and the center of our schools–Eucharistic piety? What kind of example of love for the Holy Eucharist do we give to our schoolchildren? In 1847, numerous letters were written to the bishop about St. John Bosco and the piety of his boys. "He's being too excessive, he's too rigorous, he's too disciplined; he's making these children too pious; you've got to stop this thing; it's no good." Such a fact clashes with our perception of St. John Bosco being soft.

St. John Bosco was extremely strict as to the formation and virtue of his leaders because leaders are Christ among the children. We must do likewise in our formation of principals and faculty. Pope St. Pius X set the spirit and tone of his pontificate in his first encyclical, E Supremi Apostolatus (Oct. 4, 1903) where he wrote:

The times we live in demand action, but action which consists entirely in the observance, with fidelity and zeal, of the divine laws and precepts of the Church and in the frank and open profession of religion.

Think about this. When teachers are together, how often do they speak about religious things? How can we expect children to keep from thinking that religion is not important if we're afraid to openly profess and practice spiritual things? Let's read some St. Augustine and break it down to the childrens' level: "Hey, I'm reading this great story about St. Augustine..." Everyday at Mass, there's something to turn on the light bulb. Let's ask ourselves, "How can I bring that up? How am I going to discuss that?" Religious instruction is not just when the teacher is in class as the master. Teaching must be done as our Lord would have often done with the Apostles–informally. This is an important apostolate in the direction of souls.

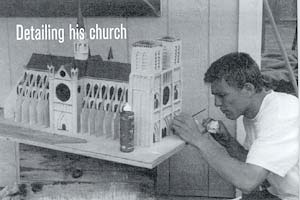

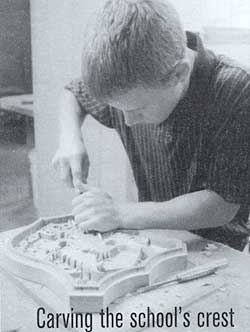

The manly piety of St. John Bosco results in manly behavior, attitudes, prayer, and devotion. It touches everything, even art and music. I'm speaking in the context of my experience in a boys' school, but even so, let the girls be "manly," too, in this sense. We've had enough of the "girly" piety; let's start putting some manly piety into these things. Look around at the statues in your school. In some missions, it makes you sick. "Man, how can they have that picture up?! Do they really have boys looking at that picture?!" Finding objectively good art is definitely difficult–though easier now than ever before–but it's worth the effort. If we can't afford to buy it, we'll have to make it for ourselves, like we do at St. Joseph's....The boys have helped paint the statues, altars, even make the stained glass. It's necessary that the art and decoration of the school be permeated with the Christ-like manly strength we are trying to form in the children. Don Bosco was rigorous in making his leaders integrate all things into the formation of his children.

Another aspect of religion is the value of confession. Essential. St. John Bosco said the confessor was the key component in his educational system. He extolled the bond, the relationship, a confessor–not tyrannical, not Jansenist–could have over a young person when this sacrament was properly administered. He says children should be encouraged to have a regular confessor, that is, a priest that they most often go to. A child should be allowed the liberty to go to someone else at times, but when we've established the proper rapport as a father with the child, it is less likely he will go elsewhere. Remember, what are our moral duties in the confessional?–It's not just to be the judge: it's to be a teacher and father. Even when they commit that bad fault, they're going to want to go to you because they know you're the one who knows them. We're not simply distributors of this Sacrament's graces. We've got to take the time. "Man, it's Tuesday afternoon; it's time for confessions; it's going to be an hour and 15 minutes." We must see in this Sacrament an opportunity to get into the soul and psyche of the child to effect further formation. This is why Don Bosco was such a proponent of the necessity of frequent confession and a particular confessor.

St. John Bosco let the children see him get into line once a week. It was important to him to prepare himself properly, get in line with the boys, and go to confession with them every week. It wouldn't be a bad idea for us and our teachers to do the same once in a while. In Don Bosco's day, schoolmasters had schoolchildren produce a "bill of confession" from their pastor proving they'd gone to confession. Don Bosco had none of that. You just came to him whenever you wanted. He heard confessions every morning before Mass and before lights-out. It's an example. He was showing his boys how important this thing was by being in the confessional every single morning, every single evening, every single day for the 40 years he was in Turin. Sometimes he would hear confessions through the night! The stories are legendary. What does that say to children? "If that guy, who is the leader here, thinks that my soul is so important he puts himself into that stuffy box, that he doesn't eat or sleep, I guess my soul is pretty important!" This has an incredible effect on a young mind. Just what St. John Bosco wanted.

Sodalities were a major part of the Salesians, some dedicated more to prayer, others to action. They were part of a mental universe from which religious vocations came and also a key way by which Don Bosco formed his leaders. This is something of which we must be constantly conscious in our schools, especially in our boarding schools, though the application is to all schools. We must be on the lookout to identify the leaders and future leaders. Unfortunately, it's the choleric child who might rub us the wrong way, yet he is the leader. We have to be extra patient with him. We're not spoiling the child just because we're more solicitous of him. On the contrary, we're being more solicitous for the whole school by identifying and helping its leaders. That's why St. John Bosco called together the leading guys, stuck them in sodalities, and spent a lot of time attending their meetings, exhorting them to be faithful and rekindling their enthusiasm for the sodality.

The last point under the religion aspect of education is what Don Bosco called the "pedagogy of duty." Real adults are people of duty. Adults accomplish their religious, civil, and family duties. That starts with the priest. Teachers who know, who love, who perform their duty, who truly enjoy and love their state of life and aren't constantly complaining about all the unfortunate things with which they have to deal–that's virtuous.

The first step to this virtuous discretion is building fraternal charity amongst ourselves. At table and elsewhere, teachers should be able to speak freely and know that certain things are safely in the confidence of each other. How in the world does Mrs. W. find out what teachers thought was exclusively among themselves? And where does that go? Faculties must be the tightest of family units, otherwise we'll find it necessary to confide imprudently in others.

We and our teachers have got to build friendships with each other. Sometimes that can be difficult depending upon where we're assigned, but that can be worked on. When a fighting husband and wife come for advice, the first recommendation we offer is that they start communicating, that their whole problem started five years ago when they stopped talking together. What about amongst ourselves? Teachers may tend to do their thing, grumble about each other, can't wait to get away so they can talk to So-and-So...."Ah, the First Grade teacher is driving me nuts. I can't stand this place anymore." The noble ideals of duty and honor and family must be sought by educators before they can demand them from the children.

In his book Dedication and Leadership, the former Communist Douglas Hyde says the problem with the Catholic Church is that it's not demanding enough of its youth. Communists demand: "You're going to get half the wages, live like a pauper, and die in a street, but you'll do it to further the progress of the people." If we want the same loyalty to the Catholic Cause from our children, we've got to live it first. We've got to really believe it ourselves otherwise children will sense our hypocrisy. They know if we're just telling them things and not doing them ourselves.

This idea of duty was exemplified beautifully by St. John Bosco during the 1854 cholera epidemic. People were sprinting out of the city, dying; they needed help. He decided that he was going to treat as many people as he could and asked his boys for volunteers. "Whose going to come? You have a good possibility of catching this thing and dying." A whole bunch of boys went with him. They went through the whole city helping, aiding, comforting these people, and not one of them got sick. What inspired their volunteerism was St. John Bosco's devotion to duty. He didn't make anyone do it. He asked for volunteers; they followed him in and did it.

KINDNESS

We finally arrive to Kindness, that is, the reaching the hearts of the young as a good father reaches the hearts of his children. Love conquers all. When Don Bosco was asked to summarize his whole system, his priestly life–everything–he quoted I Corinthians, chapter 13:

Charity is patient, is kind: charity envieth not, dealeth not perversely; is not puffed up; is not ambitious, seeketh not her own, is not provoked to anger, thinketh no evil; rejoiceth not in iniquity, but rejoiceth with the truth, beareth all things, believeth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things...."

Other than the concrete manifestations of Our Lord Himself in the Gospels, this is the summit of the Sacred Writings on charity: "...is patient, is kind...." Win the heart of the pupil, says St. John Bosco, and you'll be able to exercise great influence over him for the good. Let us make ourselves loved and we shall possess their hearts. And once we have their hearts, assuming that we are righteous and good men, we'll lead them where they need to go.

The possession of their hearts will happen by kindness, which, according to the Holy Ghost through the pen of St. Paul, is a manifestation of charity. The Introit for the feast day Mass (Jan. 31) in honor of St. John Bosco is striking:

God gave to him great wisdom and understanding exceeding much, and largeness of heart as the sand that is on the seashore. (III Kings 4:29)

In a special way, this is the goal of those who are educators of children, to make their heart as vastly charitable as the sand on the seashore. The stories of St. John Bosco's kindness are endless. How about the one of the sacristan giving the kid a beating, "Get in there, serve the Mass!"..."I don't know how to serve the Mass!" "Then get out of here!" St. John Bosco hears the noise, looks down the corridor, "Hey, come here. What's going on here?" "Ah, the kid doesn't know how to serve Mass." "Whoa, wait a minute, come in here," says Don Bosco who talks kindly to the boy. "Do you know your religion?" "No, I don't even know how to make the sign of the cross." St. John Bosco tells him to come back later. He spends time on the kid. This kid is won. What does he do? The next week he comes back with three of his friends. "You've got to come here. This guy is a good guy. He's actually given me something. He cares." All for a little bit of kindness which is the hallmark of the saints' lives.

Charity manifests itself in kindness and kindness produces cheerfulness. One of the primary fruits of the Holy Ghost is joy. If there's not joy in our lives, in our teaching apostolate, there's a problem. In a well-regulated, well-accomplished, spiritual life, there should be joy, that is, cheerfulness. It has to be there. We have to make the Faith, the practice of the Faith, agreeable. That's the proper way it should be. It's not just a negative thing. It's not in the constant condemnation of things. If we put before the children the beauty of our holy Faith and its sacraments, the beauty of the Mass, and the beauty of the life of Our Lord Jesus Christ, that's going to eventually attract youngsters.

How are we to be joyful? First of all, in the actual practice of charity, which is difficult sometimes. In the concrete case, we clash with some kid. We just don't like him, but that doesn't spare us from trying to be charitable. We have to work on that.

Practically, we can engage the children in putting on theatrical performances. St. John Bosco was big on these.

The talent show at St. Joseph's Boys' School at Christmastime is a sure winner. We have a major theatrical production at our Commencement Weekend, often Shakespeare. The boys get into this thing. It's an expression of joy and charity.

Music and singing. St. John Bosco said, "A school without music is like a body without a soul." Read Archbishop Lefebvre! He wanted us to give our schoolchildren 20 minutes of Gregorian Chant every day–the best of music. Children like marching music. Military music attracts the ears of boys, especially. St. John Bosco's boys were good at singing, being playful. They were manifesting Christian joy in honest and legitimate fun.

Excursions and outings are a key. Plan them and go on them. Priests ought not just tell the teachers to organize these things, but make it something with which they get involved, especially if you have boys. We don't have to do anything imprudent, but we ought not go to the other extreme and go window-shopping..."OK, that's it, no more outings, no more excursions. Don't do anything with the boys off school property because it's possible someone's going to get hurt...."

St. John Bosco believed in the "pedagogy of praise," which is part of offering joy to our schoolchildren. The kind word. It's being aware of those times when we can praise the child honestly. St. John Bosco had a custom he called "Letters of Praise." When a boy did something outstanding, Don Bosco wrote a letter of praise, gave a copy to the boy, and sent the letter to his parents...."That's going in your file, son. This was outstanding." Balanced, not excessive, not whipping out praise without reason. Merited praise. Look to praise them properly. Excessive praise corrupts and so does the failure to praise. Praise them as Our Lord would have praised the Apostles. "Virtue stands in the middle." If we don't recognize their good efforts, good efforts dry up.

Recognition of effort strengthens our rapport with the child and makes correction go down more easily. If we've praised them when they've done good, they know our correction, when it is given, is fair and honest... "I didn't do my homework today. When I do a good job, my teacher says, 'Hey, good job–a real good story you wrote there!'" Then, the next time when he doesn't hand it in, my teacher says, "That was a poor job." Educators don't have to get extreme. That's what St. John Bosco says. All that's needed is that look from them which says, "You know, I'm really disappointed in you. You really didn't do a very good job." That's enough. That's correction enough. There's no need to administer any "creative" punishments.

An extension of this is what St. John Bosco called the "word in the ear," in Italian, parolina. It was an intimate corrective method. Personal. A confidence-builder for the child. It requires contact of the superiors with the children because we can't be whispering a confidential word in someone's ear if we're never near them, if we're off in our "splendid isolation." This kind of contact is outside the classroom. We're on the field with them or on a walk, a field trip. Maybe Johnny's not been doing well lately and now we've got the chance for a little quiet word. "Come on, you did really well the first quarter; what's going on now? Come on, a little bit more. Give us a little effort." It's what we all like. "Wow, he knows; he cares." We all know this has a huge psychological impact. When a superior shares an intimate word with us, we say, "He trusts me to have actually talked to me about that." That has immense psychological benefits.

St. John Bosco was against the idea that obeying God's law meant misery. He said this was absolutely false:

I would like to teach you children how to lead a Christian life which will make you happy and content and I will show what true enjoyment and fun are that you can make your own the words of King David and say, "Let us serve the Lord with gladness."

Consider the pontifical High Mass sermon of Giuseppe Sarto given at his installation as Patriarch of Venice. He addressed the parish priests, clergy, magistrates, nobles, the rich, sons of the people and the poor: "You are my family. You are the object of my love and I hope that you will love me in return." That is the future Pope, the future Saint, our patron. This has to be applied to the children we're dealing with: "You are my family. You are the object of my love and I hope that you love me in return." That's the spirit of restoring all things in Our Lord Jesus Christ.

The young must not only be loved, they must be made to feel that they are loved. They have to know that you love them. A vision of St. John Bosco is illustrative. Two former pupils appeared to Don Bosco, one showed him the Oratory at its foundation and the other showed him the same place 25 years into the future. There was a huge difference. In the vision of 25 years later, the priests and brothers still loved the boys apparently, were spending hours preparing for their classes, were praying for them, but the boys were sullen and not doing what they were supposed to be doing. "What's going on here?" asked the boy in the vision. St. John Bosco answered, "They still love them, that's true. But they're not showing them that they love them. The boys don't know they are loved." It's not a question of conceptual charity; it's the expression and manifestation of that charity. What's the incarnation? God so loved the world that He manifested that love concretely by taking human flesh. The children must not only be loved, they must know they're loved.

St. John Bosco counsels us to make ourselves loved, not feared. The sternest disciplinarian, says Don Bosco, loves his charges with a manly charity–nothing gushy or sugary–which is reciprocal. If we show this kind of sacrificial love, we can be as firm as we have to be. Speak to the child in such a manner so that he is happier and better, knowing he has a chance for resurrection. Even the moment of correction is an opportunity to foster our rapport with the student. What's our goal in correcting someone, especially a child? It's not only to punish. We're not talking about a hardened criminal; we're talking about a Catholic child who is coming to his Christ-like figure. Our goal in correction is to make him better. Anything short of winning his heart isn't going to work. Win the child's confidence by destroying distance barriers. In the classroom, we're magisterial. We must conduct ourselves with a certain gravity and dignity. It's not a question of letting ourselves down, having kids come up, put stupid hats on our head, slap us on the back, and make us look like a fool. If that happens, we've lost our authority and we're a weak leader. A strong leader, a man who is self-assured with the grace of Christ, can put himself into the middle of boys and not lose an ounce of his dignity, can gain their hearts and win their confidence. That's entirely possible because it's already been done. Great Catholic men, Catholic educators, have done it. Distance kills. Without rapport, we cannot conquer the heart; without conquering the heart, we can't bring our children to the ultimate objective of loving and living the Faith. That's got to be in our heads. We're forming this perfect Christian and every ounce of sweat and blood we spend is for that goal.

The primacy of the Blessed Virgin Mary throughout is very important. She is not just a pious thing to add on to the end. St. John Bosco's whole life was given over to Mary, Help of Christians. That's the appellation of the crusaders which St. Pius V put into the Litany of Loreto–Mary, Help of Christians. It must be her spirit that radiates throughout our efforts. If we've reduced her to just a little pious exhortation, that's nice and it sounds good, but then it's best not to mention her at all. Like St. John Bosco, we must be sure we're living the devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary and letting her live in our teaching apostolate.

I hope this has helped somewhat. May St. John Bosco lead us to our Lord through our Lady.

Transcribed by Angelus Press. Fr. Michael McMahon is a 1989 graduate of Yale University. He was ordained in 1996 for the Society of Saint Pius X. He was the first director of St. Bernard Pre-Seminary in Manila, the Philippine Islands. He is stationed at St. Joseph's Priory and Boys' Academy (Richmond, Michigan) where he teaches Religion, Latin, and Physical Education. His presentation was adapted and edited to maintain its original conversational tone by Fr. Kenneth Novak. The pictures used in this article were borrowed from Frs. McMahon and Novak, Bro. Marcel Poverello, and the St. Joseph's Academy archives