The Americanist Vision Since 1932, Pt. 2

Democracy Congruent with Catholicism

Part 2

Dr. Justin Walsh

The Americanism of [John] Ireland...embraced American democracy and culture as congruent with Catholic ideals....Now, as this history of the Knights makes clear, every major phase in the evolution of Columbianism embraced the Americanist...vision.1

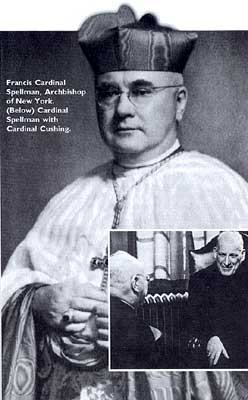

Spellman and Cushing: Patriotic Prelates of American Liberty

Due to inept leadership, the patriotism of the Knights did not shine forth as brightly during World War II as it did during World War I. In the words of Christopher Kauffman, "intensive battles [between officers] occurred behind the scenes which severely distracted the [Order] during this world conflagration."2 Another reason the Knights of Columbus took a back seat was the hostility of Archbishop Francis J. Spellman of New York, the most powerful prelate in America during the war.

In 1925, while a parish priest in Boston, Spellman was appointed by the NCWC (National Catholic Welfare Conference) to oversee a program for delinquent youth in Rome, a program that the Knights of Columbus sponsored for the Vatican. Fr. Spellman broke with the Knights in 1931 when the Order "inverted its priorities" by expending $50,000 on the Gibbons Memorial while it could not find $5,000 for the Vatican's youth project. Spellman was leery ever afterwards of the Knights.

In 1942, with the blessing of the NCWC, President Roosevelt named Spellman, now Archbishop of New York, Military Vicar of the Armed Forces of the United States. This vicariate was ecumenical by definition in that it embraced members of all creeds and sects. One biographer said Roosevelt selected the Archbishop because Spellman's "vision is world wide, [while] his patriotism is a white-hot flame." He used his position to keep the Knights of Columbus out of all service connected programs.3

The generation that came of age between 1925 and 1950 saw the Military Vicar of the Armed Forces as a personification of patriotism and conservative orthodoxy. The Vicar gained sufficient renown for Pope Pius XII to elevate him to the College of Cardinals in 1946. As Cardinal Spellman, he retained his Military Vicariate until his death in 1969. During the war he "followed the boys" almost as frequently as Bing Crosby and Bob Hope, the Hollywood duo famous for its tours to entertain the troops. In 1942, Crosby starred in The Road to Victory, a film produced by the government to boost patriotism and sell war bonds. Spellman borrowed the title for a book of patriotic sermons. He dedicated the compact collection of eleven homilies, distributed free to military installations and public libraries, "to our 'Sweet Land of Liberty,' [for] the soldiers, sailors, and marines, who are in the forefront of the battle for our country's life." The message of religious plurality (or indifferentism) was intended to please all servicemen regardless of creed:

Long before the birth of our Republic...the Church proclaimed...that all men are equal in their natural dignity, their destiny, and in their right to recognition by all their fellow human beings. This philosophy of government...make[s] it indeed crystal clear that America is fighting for the God-given rights which the Church has defined through the ages. The "credo" of the founding fathers of this country, the "credo" of the builders of our nation, the "credo" of the great-hearted, great-souled America, enunciates the truth that the individual has natural rights, that all men are created politically free and equal by Divine and natural law, that sovereignty resides in the whole people and its object is their common welfare, and that representatives in this sovereignty are selected by the people and are responsible to them.4

To Catholics on the homefront—the men, women, and children in the parish pews—these were indeed words of reassurance. America was on God's side. Archbishop Spellman said so, and Catholics knew intuitively that God, as well as President Roosevelt, listened to the Archbishop.

Spellman concluded his book with a warning that "We must keep God in Americanism, for Americanism without God is synonymous with Paganism, Nazism, Fascism and Atheistic Communism." The statement summarized perfectly the fervent feeling of American Catholics during the war years. Before they casually nodded their agreement about God and Americanism, however, American Catholics should have understood that Spellman referred not to the Triune God of Roman Catholicism. Rather, he spoke—albeit unwittingly—about the amorphous God of religious liberty, the deistic God of the Founding Fathers, the ecumenical, all-American "God" of Luke Hart's "Pledge of Allegiance." The inevitable end for a society that worshipped such a god is the apostate, neo-pagan, American Church and State of the 1990's. As Fr. Francis Thornton noted in his biographical sketch of Cardinal Spellman, "In The Road to Victory he realistically demonstrated...a patriotism of the highest order." When bishops become as blinded by patriotism, of either a high or low order, as Spellman became, integral Catholics can only pray, "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do." After a visit to troops in Korea in 1953, seven years after his elevation to the College of Cardinals, Spellman's patriotism reached ethereal heights that "seemed to fuse the Church and the nation into a single shining idea" according to Charles R. Morris. The Cardinal wrote:

Precious and wondrous still is our flag, which joyously and proudly I have seen flying aloft in all corners of the world, the flag of freedom that symbolizes justice and love of man for God and his fellowman....Red with charity for all men of good will—Red too with courage to achieve the liberties of men by personal suffering and sacrifice; White for the basic righteousness of our national purpose; Blue for our trust and confidence in God, our heavenly Father, and, for those who are Catholic; Blue too for the Mother of God, to whom our forbears in Faith long ago consecrated this land of loveliness.7

Richard J. Cushing replaced Spellman as Auxiliary Bishop of Boston when the latter went to New York. Cushing became Archbishop upon the death of Cardinal O'Connell in 1944. He marked his tenth Anniversary in 1954 with a pastoral letter offering "thanks" to God, "love, loyalty, and prayers" to Pope Pius XII, and "my life and service" to the "dear people" of Boston. The diocesan newspaper reviewed Cushing's career in a special supplement where the faithful could "find the story of fervent parish life, of more young people...dedicating themselves to the poor and the needy, giving of their time, their service, their money their love, their example of holiness."8

In a talk to the Lowell Hebrew Community in February 1956, Archbishop Cushing clothed his repressive policy, the very antithesis of Christian charity to ward brethren in the Faith, in a veneer of patriotism tolerance, and ecumenism:

Any Catholic who reviles or wrongs a brother because of the color of his skin, because of race or religion, or who condemns any racial or religious group, ceases in that condemnation to be a Catholic and an American. He becomes a disobedient son of Mother Church and a disloyal citizen of the United States.

A biographer put it best:

If ever a modern priest tried to be all things to all men...Cardinal Cushing is that man. There are so many pictures of him in so many touching roles that the biographer is hard put to select his outstanding accomplishments. He worked well and lovingly in all he did, and as a result, there is near perfection in all his activities.9

He was elevated to the College of Cardinals by Pope John XXIII in 1958. So it was as a Cardinal that Cushing attended Vatican II in tandem with Cardinal Spellman and John Courtney Murray, S J., the high priest of religious liberty, who served the America prelates as chief "peritus," or expert theologian.

Cardinal Cushing's auxiliary bishop, John J. Wright, attended Vatican II as the Archbishop of Pittsburgh. He was elevated to the College of Cardinals by Pope Paul VI in 1966, and, as Cardinal Wright he addressed the 1969 convention of the Knights of Columbus. Wright and Supreme Knight John McDevitt (1964-1977) "knew each other from early days in Boston. Both embraced aggiornamento," says Kauffman. Of Wright's speech on "A Church of Promise," Kauffman says that while it included a lengthy tribute to the Knights, "it was primarily an explication of Pope Paul's vision of the mission of the Church in the modern world."10

Both Cardinal Cushing and Archbishop Wright helped devise the Catholic position on religious liberty that was articulated in 1960 when John F. Kennedy was elected President of the United States. One source says "Cardinal Cushing swore, and probably believed, that he had planned [the presidential campaign] with old Joe Kennedy in the Boston chancery office."11 Kennedy, a Fourth Degree member of the Knights of Columbus, implemented the strategy in a way that won plaudits from Catholic and non-Catholic liberals alike. "Kennedy faced the [religious] issue frankly and early in his campaign," said Leo Pfeffer, counsel for the American Jewish Congress. "He disarmed many of his opponents by declaring unequivocally his commitment to the principle of the separation of Church and State...."12

Pfeffer's comment was directed at Kennedy's address before the Houston, Texas, Ministerial Association on September 12. Christopher Kauffman felt the talk reflected "traditional notions of Columbianism." Regarding the Alamo, Kennedy noted that "side by side with Bowie and Crockett died McCaffey and Bailey and Carey, but no one knows whether they were Catholic or not. For there was no religious test...." Best of all, in Kauffman's view, Kennedy pledged himself to an America "that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant, nor Jewish...and where religious liberty is so indivisible that an act against one church is...an act against all."13 The heresy endemic to American Catholicism from the beginning of the United States is the poisonous source of both "the traditional notions of Columbianism" and Fourth Degree Knight John F. Kennedy's vision of a nation "that is neither Catholic, Protestant, nor Jewish." Historian Kauffman's account of the ceremonial for the Fourth Degree, "orchestrated" on the theme of Catholic citizenship, is definitively instructive on this point.

The ritual begins when the Chancellor of the Degree Team declaims on pride to the candidates. "Proud in the olden days was the boast: 'I am a Roman Catholic'; prouder yet today is the boast, 'I am an American citizen'; but the proudest boast of all times is ours to make, 'I am an American Catholic citizen.'"

The historical "lessons" about such citizenship include "a lengthy litany" of the contributions of Catholic explorers and missionaries. This is followed by the story of how Catholics in the colony of Maryland introduced religious toleration to British North America. The sequence ends with praise for the "patriotic prelates Carroll, Hughes, Ireland, and Gibbons." After the history lesson, candidates are reminded of "what our republic has done for the Church." Kauffman quotes from the ritual: "Under laws of toleration and freedom she the Church has enjoyed a peace and progress, a prosperity and growth unequalled and beyond all expectation."

To place Kauffman's conclusion within its proper perspective, the reader should remember that in 1899 a Pope explicitly condemned the Americanist heresy. Nonetheless, Kauffman wrote, "To place the spirit of the Fourth Degree within its proper perspective, one should recall specific trends within the Order, the Church, and American society at the turn of the century." He stressed that Columbianism was analogous to the Americanist ideals of Archbishop John Ireland in that both identified America as a land where Catholicism and democratic freedom existed "in a symbiotic way. In the relationship, Catholicism brought out the best in American freedom, and within American freedom Catholicism progressed to a higher stage in its development."14

Dr. Justin Walsh has an undergraduate degree in Journalism and a Master's degree in History from Marquette University and a doctorate in History from Indiana University. He currently teaches at the Society of Saint Pius X's St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary, Winona, MN, USA.

1. Christopher J. Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism: The History of the Knights of Columbus, 1882-1982 (New York: Harper & Row, 1982), p. 367.

2. Ibid., p. 342.

3. For Spellman conflict see ibid., pp. 324-326. For Spellman's career, see "Francis Cardinal Spellman," Francis Beauchesne Thornton, Our American Princes: The Story of the Seventeen American Cardinals (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1963), pp. 201-217. Spellman was born in South Boston in 1889, the grandson of Irish immigrants. He attended the North American College and was ordained in Rome in 1916. While in Rome in the 1920s the Bostonian became a friend of Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the Vatican Secretary of State. He returned to Boston in 1932 as Auxiliary Bishop with the right of succession to William Cardinal O'Connell. Then in 1939 former Secretary of State Pacelli, now Pope Pius X1I, selected Spellman to fill a vacancy in New York, the largest archdiocese in the country. On Spellman's recommendation Richard J. Cushing, another Irishman from South Boston, was named Auxiliary Bishop with the right to succeed O' Connell.

4. Francis J. Spellman, The Road to Victory (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1942), pp. xi, 1-2.

6. Thornton, Our American Princes, p. 216.

7. As quoted in, Charles R. Morris, American Catholicism: The Saints and Sinners Who Built America's Most Powerful Church (New York: Vintage Books, 1997), p. 277.

8. For anniversary letter see Thornton, Our American Princes, pp. 235-236.

9. Thornton, Our American Princes, speech to Lowell Hebrew Community, p. 244; biographer's evaluation, p. 241.

10. Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, pp. 410-411.

11. Morris, American Catholicism, p. 28l.

12. Anson Phelps Stokes and Leo Pfeffer, Church and State in the United States (New York: Harper and Row, 1964), p. 334. Stokes, the author of the first edition in 1950, died in 1958. So the material on the 1960 campaign was written by Pfeffer, whose sentiment regarding Catholicism is revealed in his Beacon Press book Church, State, and Freedom (1957): "To the Jewish child devoted to the religion of his fathers, the New Testament in its entirety is blasphemous for attributing divinity to a human being."

13. Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism, pp. 392-393.

14. For the Fourth Degree ceremonial see ibid., pp. 139-140.