MALTA OF THE KNIGHTS

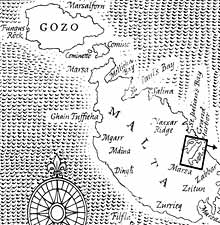

It was a time of contention and warfare. The Knights Hospitallers of the Order of St. John had just been defeated in the Siege of Rhodes by Sultan Suleiman that year, 1522. Having no place to call their own, the vagrant knights were offered the fiefdom of Malta through the goodness of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, acting as King of Naples. This archipelago, composed of two main islands, Malta and Gozo, is located 50 miles off the south coast of Sicily, and commands the main Mediterranean trade channel (see map on pp. 12-13).

In 1557, Jean Parisot de la Valette was unanimously elected Grand Master. He was a handsome man, calm and unemotional, who demanded nothing of his knights that he himself could or would not do. Meticulous in his religious observances, he was the finest general and admiral that the Order had known in many years.

Suleiman had come to regret his decision that gave the knights safe passage from Rhodes; he now turned his eyes to the possession of Malta as propitious to his conquest of Western Europe. By the late autumn of 1564, it was indeed true: La Valette's spies had given him information that a huge Turkish armada was being mobilized against Malta. The message reached knights of the Order who were residing at their estates or attending the Courts of their respective Sovereigns.

Thus the early months of 1565 saw the island feverishly preparing for the onset. Although at first the knights had found Malta to be unbearable, the Grand Master and his Council could now see that the whole island was a natural fortress. Its barrenness meant that any invader would have to bring almost all provisions with him. The Turkish army would find it impossible to live off the land.

La Valette presumed correctly that the Order could expect little help from the Christian princes. Francis I of France was allied to the Sultan from a treaty in 1536, and the Emperor of Germany was far too concerned about the havoc Suleiman's men were constantly causing in his lands to be able to look as far south as Malta. England's Protestant monarch Elizabeth I would obviously send no help.

It was then only from Spain, now under Philip II, that La Valette could expect any assistance. Malta had been a Spanish gift to the knights; if the island fell, it was the lands and dominions of the Spanish crown that were immediately threatened–first Sicily, and then the Kingdom of Naples. Pope Pius IV sent them 10,000 crowns, which was somewhat useful but did not resolve La Valette's lack of manpower.

By the early spring of 1565 La Valette had under his command 541 knights and sergeants, 5,000 Maltese irregulars, and 500 galley slaves. Later in the spring more knights arrived in answer to the Grand Master's appeal. When the Turks arrived he had 700 members of the Order and a total force of almost 9,000 men. With this he must withstand the full weight of the Turkish navy and army, for if Malta fell, the Order of St. John would surely perish, and the rest of Western Europe would be threatened.

Throughout the winter of 1564-65 the Sultan spared no expense in the preparation of his greatest armada. With confidence he appointed Mustapha Pasha as commander of his army. This fanatic Moslem had fought against the knights in Rhodes and carried a personal vendetta against Catholics with typical Islamic fanaticism. He aspired to seal a triumphant career by driving the Knights of St. John once and for all out of the Mediterranean.

As Mustapha's co-commander Suleiman appointed Admiral Piali. Not as savage as his commander, Piali had been baptized Catholic, but had forsaken all for a seafarer's life. At this time he was at the height of his powers. Among his numerous maritime successes had been the great raid of 1558, when he and the corsair1 Dragut had laid waste great stretches of the Italian coastline. Suleiman instructed the two commanders that they should await the arrival of Dragut before beginning the main assault.

March 29, 1565. Suleiman was there in person to view the power and pride of his Empire afloat on the waters of the Golden Horn as they set sail from the Bosphorus. One hundred and eighty-one ships and a number of small sailing vessels formed the armada. One hundred and thirty oared galleys and 30 galliots2 (see inset this page) were accompanied by 11 large merchant ships, of which one alone held 600 armed men, 6,000 barrels of powder, and 1,300 rounds of cannon ball. Valette could not have fathomed just how many ships nor how huge an army the Sultan had raised against him.

The Turks numbered at least 40,000 trained fighting troops, not to mention the many thousands of slaves and other supernumeraries who were required to provision and supply so large an army. Six thousand three hundred Janissaries, the finest troops in Turkey, formed the spearhead of the fighting troops, all trained arquebusiers and the elite of the Ottoman army. Catholic by birth, Spartan by upbringing, and fanatical Moslems by conversion, the Janissaries formed one of the most amazing corps in military history.

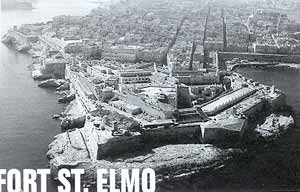

Meanwhile Grand Master La Valette completed his preparations. Birgu and Mdina (the capital of Malta) were warned about the upcoming onset, and orders were given for most of the population unable to bear arms to take refuge within the walls of Mdina. Similar commands were sent to Gozo, ordering the country people to shelter in the citadel as soon as the attack started. It was probable that St. Elmo, a newly built and untried fort, might have to bear the first onslaught. The choice of garrison, therefore, was of the utmost importance. Its normal garrison was only six knights and 600 men. Valette reinforced them with a further 200 Spanish infantrymen and 46 knights. Fort St. Elmo was to be the scene of one of the most glorious episodes in the history of Christendom.

In mid-May, La Valette called together all his brethren. It was the last opportunity that he would have to speak to them in general assembly. There were many present whom he would never address again.

It is the great battle of the Cross and the Koran which is now to be fought. A formidable army of infidels are on the point of invading our island. We, for our part, are the chosen soldiers of the Cross, and if Heaven requires the sacrifice of our lives, there can be no better occasion than this. Let us hasten then, my brothers, to the sacred altar. There we will renew our vows and obtain by our faith in the sacred Sacraments, that contempt for death which alone can render us invincible.

When the knights left the church, they were filled with exultation. "No sooner," it was said, "had they partaken of the Bread of Life that every kind of weakness disappeared. All divisions between them and all private animosities ceased."

Upon the arrival of the Turkish armada, La Valette decided not to contest their disembarkment. Mustapha Pasha gave orders for siege guns to be dragged to Mt. Sciberras. Two 60-pound culverins,3 ten 80-pounders, and an enormous basilisk4 firing solid shot weighing 160 pounds were brought up for the attack on St. Elmo. With such heavy weapons, the battering power of Turkish fire when applied at short range would be devastating.

Less than a week later the order to commence the attack was given. Within an hour the lime and sandstone blocks that composed the fort began to crumble as the Turks relentlessly, mathematically, hammered away at the fort. Ace artillerymen were not to be deterred by this small fort on this relatively unimportant island. But the Turks did not know the extent of the defender's capabilities. Under cover of the grey pre-dawn sky, the besieged knights made a sortie, stealthily lowering the drawbridge and capturing the closest enemy trench. The tired Turkish labor corps, who had been working all night, were taken completely off guard and fled across the bare heights of Mt. Sciberras.

"Janissaries forward!" Mustapha commanded. In assault or defense, in innumerable campaigns, in many countries, there would come a time when this cry would go out. To stem a panic or turn a wavering victory into a certainty, it was for these that this corps was especially designed. They were thrown into the balance to ensure that the scales would tilt in favor of Allah.

As the disorganized labor battalions fled past them, these invincible soldiers surged ahead. Before the advance of these supreme warriors the defenders fell back, only reaching safety in time for the cannon above them to open fire on the advancing ranks of their enemies. Nonetheless the Janissaries were still able to recapture their own trenches and established themselves in a strong position right in the teeth of St. Elmo. Though driven back into the confines of St. Elmo, the fighting spirit of the knights was undiminished.

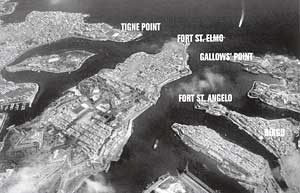

The Turkish forces were strengthened by the arrival of the 80-year-old corsair Dragut, the great scourge of the Catholics in the Mediterranean. Known among his men as "The Drawn Sword of Islam," this fierce veteran of siege warfare knew well Malta and its terrain. For this siege he brought with him 1,500 of his choicest warriors armed to the hilt. Once there, they set up on Tigne Point, facing St. Elmo from the north (see map). The corsair at once noticed what Mustapha and his advisors had not: St. Elmo's strength lay in the reinforcement of their garrisons by boats nightly sent from Fort St. Angelo (map).

The orders rang out: "Cut lines of communication. Take by force the outwork of the fortress." The troops dispersed to the scene with Dragut in the lead. He intended to see the action from the viewpoint of the men who were engaged in it. The cheers, the thunder of guns and the lights and flares seen on the slope of Mt. Sciberras by the Grand Master and his men at St. Angelo told them that Dragut had arrived upon the scene.

He took up his quarters in the trenches among the troops, and there he stayed. Within 24 hours the fire against the fort had doubled. Breaches began to appear in the walls, and fast as the defenders tried to erect counter-walls behind them, these too were shot away. They knew a mass assault must shortly follow.

There was no relief from the torrid weather of that late May. The Turks, no less than the knights, suffered from a lack of water; the Turkish army was riddled with dysentery, so much so that they were forced to erect hundreds of tents at the Marsa5 to accommodate their sick. Considering his position, La Valette had every reason to be pessimistic. The day after Dragut had arrived a small vessel from Sicily managed to run the blockade and bring a message to the Grand Master with the news that there was no hope of any timely help from Don Garcia de Toledo, Viceroy of nearby Sicily. On May 31, the Feast of the Ascension, La Valette read this dispatch to his Council:

We now know that we cannot look to others for our deliverance! It is only upon God and our own swords that we must rely. Yet this is no reason to be disheartened. Rather the opposite, for it is better to know the truth of one's situation than be deceived by specious hopes. Our faith and the honor of our Order are in our own hands. We shall not fail.

It was the morning of June 3rd, the Feast of St. Elmo. The new battery erected on Tigne Point opened a steady fire on the fortress with Dragut in charge. It was just a matter of time before an opportunity presented itself for a large-scale attack on the outwork of Fort St. Elmo. Capture it he would, no matter what.

A few days later, a group of Turkish engineers decided to inspect the ravelin.6 They found it to be very weak, and close though they came, no sentry challenged them. Nothing was seen but a few exhausted soldiers lying asleep. The inspection party slipped back to the Turkish lines and announced the ravelin to be almost deserted and that it could be easily taken. The probable reason for this lack of vigilance is that a stray bullet from one of the Turkish snipers had killed the man at his post, and his death had gone unnoticed by his sleeping companions.

Within a few minutes of receiving the news, the Janissaries flew into action. Swarming up the ladders against the ravelin's wall, they burst over the top with a blood-curdling cry. Shot down or hacked to pieces before they could gather their wits, the defenders of the ravelin perished almost to a man.

A few survivors scurried over the plank bridge that served as the link between the ravelin and St. Elmo. In a tense hand-to-hand combat, the Janissaries stormed forward from the captured ravelin and desperately tried to smash into the fort before the gates could be closed. The two-cannon surmounting the portcullis opened fire on the advancing ranks of Janissaries, managing to hold them at bay just long enough to let the remaining knights through. Red-eyed with fury, the Turkish troops still came on, storming right up to the portcullis and madly firing through its grill at those within.

"Lions of Islam!" a dervish exhorted them. "Now let the sword of the Lord separate their souls from their bodies, their trunks from their heads! Liberate spirit from matter!" Heedless of the gaps torn in their ranks by the cannon, the Janissaries filled the bridge with their troops to raise more ladders up against the fort itself. A lull in the defense, caused by the death of the knight responsible for the ammunition supply, gave the Turks enough edge to attempt an escalade. The defenders brought to bear on their attackers all their ingenuity in siege warfare. Wildfire, trumps, and firework hoops–all various kinds of incendiaries–were loosed upon the white-robed Turks. The Janissaries storming St. Elmo were subjected to a torrent of fire accompanied by arquebus7 shot, blocks of stone and cauldrons of boiling pitch. The Turks fell back into the ditch below the fort like human torches. The pork-like odor of burning flesh filled the air.

From dawn until shortly after noon, the battle raged around the bridge and the landward walls of St. Elmo, yet the flag of the Knights Hospitallers still waved above the stark ramparts engulfed in flames and smoke. Line after line of Janissaries were unleashed. The Turkish losses were heavy because of the use of fire and Mustapha was forced to call off his troops. An estimated 2,000 of the cream of the Janissary advance guard were lost that day, whereas the defenders had lost only 10 knights and 70 soldiers.

However, with the ravelin captured, the Turks were now entrenched within easy distance of the fort. While increasing their fire upon the fort, the Turks constructed a great hill above the ravelin. The conditions of the garrison worsened. With this ramp-like structure, it was now impossible to dislodge the enemy from the ravelin. The fort could only hold out if regular reinforcements continued to come every night.

It was then that Knight Rafael Salvage and Captain de Miranda arrived from Sicily with Viceroy Don Garcia's latest message to La Valette. A swift inspection of the situation convinced these men that the garrison was really as good as lost. Their grim report is still extant:

The insupportable fatigues increasing, chiefly the whole night, and the burying in the parapets of bowels and limbs of men all torn to pieces and pounded by the hostile cannon, to such a pass had the hapless besieged been reduced; never stirring from their posts, but sleeping there and eating; with all other human functions; in arms always, and prepared for combat; by day exposed to the burning sun, and by night to the cold damp; privation of all kinds, from the blasts of gunpowder, smoke, dust, wildfire, iron, and stones, volleys of musketry, to explosions of enormous batteries; insufficient nutriment or unwholesome, they had got so disfigured that they hardly knew each other any more. Ashamed of retiring for wounds not manifestly quite dangerous or almost mortal, those with the smaller bones dislocated or shattered, and livid faces bruised with frightful sores, or extremely lame and limping woefully; these miserably bandaged round the head, arms in slings, strange contortions–such figures were frequent and nearly general, and to be taken for spectres rather than living forms.

The message they brought from Don Garcia was that he could come by the end of June, if the Grand Master sent him the Order's galleys from Malta to transport the relief force. He must have known that this was impossible; perhaps he was doing no more than providing an excuse for failing to help the knights. In his reply, La Valette stressed that the relief force need be no larger than 15,000 men. He pointed out that he was sending up to 200 fresh troops every night to St. Elmo, and that this drain on the resources of Birgu and Senglea could not continue. He begged Don Garcia to let him have at least 500 men that could be transported in the two galleys which had just brought down Miranda and the Chevalier Salvage.

Rather than return to Sicily, Captain de Miranda volunteered to take a relief force to Fort St. Angelo, even though he knew this to warrant certain death. That night the Spaniard and a number of volunteer knights ferried across to the doomed fortress, together with a contingent of 100 men. The Turkish fire was now so heavy that, in the words of a contemporary, it seemed as if "they were determined to reduce the fortress to powder." As soon as the Catholic troops would build retrenchments within the shattered walls, so the battery installed by Dragut on Tigne Point would pound them away. Incapable of restraining the Muslims, the knights watched them work continuously through the night to fill the ditch where the bridge had been to connect the ravelin to Fort St. Elmo.

On Thursday, the Turks attempted another escalade. They preceded their attack by an intense artillery fire which was rejoined by a hail of bullets and incendiary weapons. As the attack began to falter, the signal to withdraw was given. Such a devastating fire was then opened on St. Elmo by the Janissaries that the defenders could neither man their guns nor take any action against the retreating Turks. The senior officers of St. Elmo decided to send a report of the latest developments to the Grand Master that same night to report the dreadful situation.

The message was relayed by the Chevalier de Medran, who suggested the fortress be evacuated at once and razed to the ground, adding the weight of its current defenders to the two main positions. His argument was reasonable, with many of the older members concurring, but the Grand Master stepped forward. He informed them that the Viceroy of Sicily had declared he would not hazard his fleet if St. Elmo were lost. "We swore obedience when we joined the Order," said La Valette. "We swore also on the vows of chivalry that our lives would be sacrificed for the Faith whenever, and wherever, the call aught come. Our brethren in St. Elmo must now accept that sacrifice."

The following night after the messengers had departed the Grand Master received an unexpected missive. All that day the guns had thundered about St. Elmo; that afternoon he had watched yet another assault made against the valiant fortress, but ultimately St. Elmo had pulled through the day. The letter read:

Most Illustrious and Very Reverend Monseigneur, When the Turks landed here, Your Highness ordered all of us Knights here present to come and defend this Fortress. This we did with the greatest of good heart, and up to now all that we could do has been done. Your Highness knows this, and that we have never spared ourselves fatigue or danger. But now the enemy has reduced us to such a state that we can neither make any effect on them, nor can we defend ourselves (since they hold the ravelin and the ditch). They have also made a bridge and steps up to our ramparts, and they have mined under the wall so that hourly we expect to be blown up. The ravelin itself they have enlarged so much, that one cannot stand at one's post without being killed. One cannot place sentries to keep an eye on the enemy since within minutes of being posted they are shot dead by snipers. We are in such straits that we can no longer use the open space in the center of the fort. Several of our men have already been killed there, and we have no shelter except the chapel itself. Our troops are down at heart and even their officers cannot make them any more take up their station on the walls. Convinced that the fort is sure to fall, they are preparing to save themselves by swimming for safety. Since we can no longer efficiently carry out the duties of our Order, we are determined, if Your Highness does not send us boats tonight so that we can withdraw, to sally forth and die as Knights should. Do not send further reinforcements, since they are no more than dead men. This is the most determined resolution of all those whose signature Your Most Illustrious Highness can read below. We further inform Your Highness that Turkish galliots have been active off the end of the point. And so, with this our intention, we kiss your hands, and of this letter we have taken a copy. Dated from St. Elmo, the 8th of June 1565.

There followed 53 signatures. In no way could the action of these knights be ascribed to cowardice. Better to die honorably against the enemy than remain as sheep waiting their turn in a slaughterhouse.

"The Laws of Honor," Valette told the messenger Chevalier Vitellino Vitelleschi in response, "cannot necessarily be satisfied by throwing away one's life when it seems convenient. A soldier's duty is to obey. You will tell your comrades that they are to stay at their posts. They are to remain there, and they are not to sally forth." La Valette sent 15 knights and less than 100 soldiers to St. Elmo. Whatever he expected of the garrison, he could hardly have dreamed that it might hold out for more than three or four more days.

From every aspect, the Turkish High Command felt that the campaign was not only going slowly but badly as well. It was now 23 days since the invasion had begun, and by all calculations, the Fort St. Elmo should have been taken long ago. Mustapha Pasha began to worry about the possibility of a relief force landing in the north and suddenly taking them in the rear. Dragut, determined that this would not happen, began to re-establish the battery on Gallows' Point (see map).

The first great night attack of the siege took place on the 10th of June. Mustapha decided as soon as it was dark that fresh troops would have every chance of catching the worn-out defenders off guard. The advancing ranks of Janissaries threw sachetti or fire-grenades, similar to those which the Catholics hurled down upon them. The Turks had perfected a type of incendiary which when it burst clung to the armor or the body, and the knights who stood in the breach were only saved from being roasted alive in their mail by leaping into great barrels of water there for that purpose. So great was the glare during this attack that a witness watching from the walls of Fort St. Michael's (see map) remembered how "the darkness of the night became bright as day." The gunners of Fort St. Angelo were able to see their attackers quite clearly and trained their guns upon them. The Ottomans stormed across the ditch in front of the fort but were repeatedly repulsed. When dawn broke, it was estimated that 1,500 of the Sultan's troops lay dead or dying in that no man's land between the ravelin and the fort. St. Elmo's losses totaled 60.

The Turks were now so enraged by the Christians that any instinct of chivalry which might have once animated their commanders had long since disappeared. The Turkish Commander-in-Chief tempted the Christians: any who wished to retire might now leave the fortress unmolested; but no one listened, for they had already resolved to die where they stood.

The following day the fire never ceased, either from Mt. Sciberras, Tigne Point, or the new batteries on Gallows' Point. Whereas the bombardment was supposed to demoralize the defenders, it merely served to put them on guard and ready them for the attack to come. The Turks, for their part, were confident that their next attack would be the last: St. Elmo's had already held out past any reasonable expectation.

The whole Turkish fleet had crept up during the night of the 15th of June, and by daybreak had encircled themselves like a ring around the fort. Four thousand arquebusiers spread themselves in a great curve and opened fire on the embrasures of the fort. North and south the batteries on Tigne Point and Gallows' Point began their cross-fire against St. Elmo.

Huddling against the walls and taking shelter behind improvised barricades, the defenders awaited the onslaught. They had fire hoops and incendiary grenades, boiling cauldrons and trumps piled high, thanks to a convoy that La Valette had managed to reinforce them with only two nights before. Along with the ammunition he had also sent further supplies of wine and bread, for St. Elmo's bakery had been destroyed and their water was running short.

For this attack–which Mustapha felt sure would deliver the fortress to him–the Janissaries were held back in reserve. Instead he first sent in the Iayalars, a fanatical corps maddened by hashish, deriving their blind courage from a blend of Religion and hemp. Frenzied with the lust to kill, seeing only the line of the battlements before them with Paradise beyond, they hurdled down for the first assault. Their salivating lips read only one word–"Allah."

Beaten back by the defenders' fire, the Iayalars were followed by a horde of Dervishes who were also driven back. The time had come for the Janissaries to advance. Again they surged towards the breach, and again they were driven back. The cannons of St. Elmo blew great black holes in the white surge of the advancing enemy.

Both Dragut and Mustapha Pasha stood in full view on the ravelin, supervising the attack. Dragut laid guns, advised the master gunners, and directed the bombardment that lashed St. Elmo all day long. No progress had been made by the time night fell and the attack was called off. It seemed incredible to Turk and Catholic alike that so small a fort could have resisted for so long. One hundred and fifty of the garrison were dead, with many more wounded. Yet 1,000 from the Turkish army died that day, with a total of 4,000 lost since the beginning of the siege.

On the 18th of June, La Valette called for volunteers to reinforce. Thirty knights along with 300 soldiers came forward, offering themselves for the post of certain death. That same day while supervising the new Turkish battery Dragut was mortally wounded by cannon shot. A second shot landing killed the Aga of the Janissaries. Mustapha, however, refused to move.

"The Drawn Sword of Islam" was carried back to his tent, weakening morale among the Turks. The following day their morale was further weakened when the Master General of the Turkish Ordnance, who ranked second only to Mustapha himself in the army, was killed.

Through the narrow streets of Birgu the Order of the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem went in solemn procession to the Church of St. Lawrence. It was the Feast of Corpus Christi–an occasion that the knights had never failed to honor. In procession through the streets they implored the Lord of Mercies not to allow their brothers in St. Elmo to perish utterly by the merciless sword of the infidel. Meanwhile the bombardment never ceased.

That Friday it seemed almost certain that the fort would be taken. Once again, the bombardment began at dawn, pummeling the fort with concentrated fire. It seemed incredible that anything could exist in that smoking ruin. Engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the layalars and Janissaries, part of the wall gave way beneath the defenders' feet, causing them to fall into the ditch. For a moment it seemed that the breach was clear of defenders, so a rush of Janissaries made for the open space. Nonetheless reinforcements managed to reach the breach in time to present once more a steely defense. It was just at this moment that the Janissary snipers, who had reoccupied the ravelin during the night, opened fire. Struck down by bullets from the rear while being attacked from the front, the defenders wavered and began to crumble. Another band of Turkish troops swept over the ditch and started to overtake the tiring men.

The position was only saved by the Chevalier Melchior de Monserrat, a knight of Aragon who had become Governor of St. Elmo after Luigi Broglia had been wounded. De Monserrat immediately brought a gun into action against the source of trouble, blowing the Janissary sharpshooters off their vantage point. But for this, the wild onrush of the Turks might well have swept over into the fort itself. Moments later, De Monserrat was killed by musket shot.

Mustapha finally acknowledged that St. Elmo could not be taken within that day and ordered the recall. St. Angelo's suddenly heard a burst of cheering from their brothers in St. Elmo. They had lost 200 men in the battle, in comparison to 2,000 Turks. But they knew the end was near, for there would be no more reinforcements.

St. Elmo's men readied themselves for a fight to the death. The two chaplains who had stayed with the defenders throughout the siege confessed the remaining knights and soldiers. Determined that the Mohammedans would not have the opportunity to mock or desecrate their holy relics, the knights and the chaplains hid the precious objects of the Faith beneath the stone floors of the chapel, and dragged the tapestries, pictures and wooden furniture outside and set them on fire. They then tolled the bell of the small chapel to announce to their brethren in the nearby forts that they were ready for the end.

In the gray pre-dawn light of the 23rd of June, Piali's ships closed in for the kill. The galleys, pointing their lean bows at the ruined fort, opened up their bow chasers in unison with the first charge made by the entire Turkish army. To the astonishment of Mustapha and his council, Fort St. Elmo held for over an hour. Less than 100 men remained after that first onslaught, yet the Ottoman army was forced to draw back and re-form. The knights who were too wounded to stand placed themselves in chairs in the breach with swords in their hands.

There was something about the next attack that told the garrisons looking on from Birgu and Senglea that all was over. The white-robed troops poured down the slopes, hesitated like a curling roller above the wall, and then burst across the fort, spreading like an ocean over St. Elmo. One by one the defenders perished, some quickly and mercifully, others dying of wounds among the bodies of their friends. The Italian Knight Francisco Lanfreducci, acting on orders received before the battle began, crossed to the wall opposite Bighi Bay and lit the signal fire. As the smoke curled up and eddied in the clear blue sky, La Valette knew that the heroic garrison and the fort they had defended to the end were lost.

It was now that Mustapha Pasha impatiently strode to view his conquest. A standard-bearer carrying the banner of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent stepped through the breach into St. Elmo. Standing victorious on the ruins of St. Elmo's walls, with the flag of St. John in the dust at his feet, Mustapha gazed at the massive bulk of Fort St. Angelo on the horizon. "Allah!" he cried. "If so small a son has cost us so dear, what price shall we have to pay for so large a father?"

In an offensive act of cruelty, he ordered the bodies of the knights to be set apart from the common soldiers. Their heads were struck from their bodies and fixed on stakes overlooking Grand Harbor. The beheaded corpses were then stripped of their mail, nailed to crossbeams of wood in mockery of the crucifixion, and launched onto the waters of Grand Harbor that night.

It was the eve of the Feast of St. John, the patron saint of the Order. Despite the loss of St. Elmo, the Grand Master had given orders for the normal celebrations to take place. Bonfires were lit and church bells were rung throughout Birgu and Senglea. The next morning the headless bodies of the knights washed up at the base of Fort St. Angelo.

To show the Turks that they were not to be trifled with, La Valette gave orders for all Turkish prisoners to be executed and their headless bodies thrown into the sea. To the astonishment of the Turks, the thunder of cannons was heard issuing from St. Angelo. Mustapha discovered that they were firing the heads of the Turkish prisoners! This was not something to be taken as a simple retaliatory gesture; the knights knew Mustapha's anger would know no bounds and that there would definitely now exist no mercy for any Catholic who surrendered. Every knight and every soldier knew that they must fight to the death against these infuriated people.

The Grand Council of the Knights met that same morning. Valette asked them. "What could be more fitting for a member of the Order of St. John than to lay down his life in the defense of his Faith?" He spoke with them further, encouraged them, and ended with the final order to take no prisoners. Every day until the end of the siege they hanged one Turkish prisoner upon the walls of Mdina.

The morale of the Knights was lifted when four galleys from Sicily managed to evade the Turkish blockade and land 42 knights and 700 militia. Under the command of the Chevalier de Robles, a distinguished member of the Order and a famous soldier, this small relief force–the Piccolo Soccorso as it came to be known–arrived at Fort St. Angelo. The next morning when he saw the new banners above the Christian fort, Mustapha was somewhat taken aback. Since he could not know the amount of reinforcements sent, he decided that now was the time to negotiate with the Knights. Mustapha knew his losses at St. Elmo had been greatly out of proportion to the size of the fort. He offered La Valette the same terms that the Grand Master Villiers de l'Isle Adam had accepted 43 years before in Rhodes–a safe passage for himself and all his followers, conditional on surrender of the island. The offer was rejected. Mustapha fumed over the knight's retort. He would take Birgu and Senglea, he swore, and put every member of the accursed Order to the sword. They, their ships, and their flag would never again trouble the subjects of the Sultan.

Siege guns were transported on to the heights of Corradino overlooking Senglea (see map), and by the end of the first week of July large-scale bombardment had begun. Some 70 guns from Mt. Sciberras, Gallows' Point, Tigne Point, and Mt. Salvatore to the heights of Corradino opened a heavy crossfire on Forts St. Angelo and St. Michael and the villages of Birgu and Senglea.

On the morning of the 15th of July, Mustapha gave the signal for the first major attack. The knights were assaulted from land and sea. From the summit of Corradino, Mustapha watched his ships move in while Hassem, Dragut's son-in-law, plunged in at the head of his Algerian troops against the landward wall of the fort of St. Michael. The sun had just risen when the attack began, and even the defenders on their threatened walls had to admit that the advance of the Moslems was a magnificent sight. Boatloads of Moslem chiefs, Turks, and Algerians wearing rich silks waded ashore, the sun catching on their gold and silver ornaments. Holding shields above their heads to protect themselves against bullets and incendiary devices, they were followed by a myriad of Turks who swarmed over the bodies of their comrades to rush ashore to prepare the escalade.

Determined to prove to Mustapha that the Algerians of the Barbary coast were more warlike and courageous than the Turks, Hassem's men were heedless of their lives. Without waiting for breaches to open in the walls, they came on in a wild screaming rush.

The seaborne attack on Senglea was showing signs of success. Chevalier Zanoguerra, the commander at this point, immediately organized a counter-attack with the help of Fra Roberto, a Brother of the Order and thus technically forbidden to carry arms. With his robe hitched up round his waist, he flew at the enemy, calling out to the defenders, "Die like men! Perish for the Faith!" Taking heart, the Catholics drove the Moslems back, only to see Zanoguerra shot dead. During the brief panic that followed, the Turks counter-attacked.

It was at this moment, when the action hung in the balance, that La Valette's foresight bore fruit. Aware that Senglea was not as strong as Birgu or Fort St. Angelo, he had had a bridge of boats built between the two peninsulas so that Senglea could be reinforced whenever necessary. When the enemy standards were hoisted above the walls of Senglea, a strong reinforcement was immediately dispatched to the threatened position. The Senglea garrison took heart when they saw their comrades coming at the run across the bridge of boats, and once again the tide of battle turned in favor of the Christians.

Like La Valette, Mustapha Pasha was watching the battle. He decided that the time had come for his master-stroke: 1,000 Janissaries aboard ten large boats had been kept back to sway the battle to their side if the need arose. He ordered the boats to make straight for Senglea, hoping that, while the defenders were engaged on the southern wall, all the Janissaries would glide unseen to the northern side and storm over the wall.

What Mustapha did not know was that Valette had positioned a hidden battery at the very base of St. Angelo precisely to stop the enemy from doing this. The Chevalier de Guiral, who was in command of the five-gun battery, could scarcely believe his eyes when he saw the Janissaries sailing straight for the muzzles of his guns. He gave the order to load. When the boats fell directly in the target range of his guns, he gave the order to fire. The entire corps was blown to pieces without a chance to retaliate. Mustapha's plan, designed to prove the turning point of the day, had turned disastrous. Nine boats were sunk and 800 men flew into the water. The tenth boat just managed to struggle back across the harbor to the slopes below Mt. Sciberras. The Maltese inhabitants of Senglea, who remembered the treatment that had been accorded the knights and the soldiers of St. Elmo, killed off the few Janissaries who had made it to land. Hence there arose the expression still used in Malta to this day, "St. Elmo's pay," for any action in which no mercy is given. Unfortunately, the Chevalier de Guiral was shot dead soon after this decisive intervention. The Turkish assault on all the forts continued, but Hassem's Algerians had suffered such great losses at St. Michael that he could hardly get them to attack. The knights opened the gate, and to seal the Moslem humiliation, pushed them to flee to their boats in disarray.

Following his abasement of the 15th of July, Mustapha adopted a more cautious approach. He decided to use the same technique as against Fort St. Elmo, reducing the walls and draining the morale of the defenders by incessant bombardment. Then, as soon as the positions were breached, he would throw the whole weight of the army against both sides at the same time. That way he would be able to prevent La Valette from reinforcing either side with detachments of fresh troops.

Though the reduction of St. Elmo had taken over a month, and Senglea and Birgu were much stronger, Mustapha felt confident that no more reinforcements would be reaching the island from Sicily. Piali's ships were on guard to the north of Gozo, ready to prevent any major relief force getting through. Notwithstanding, Mustapha strengthened his batteries and extended the entrenchments. From north and south, from east and west, the fortresses were played upon by an immense fire. During this last week of July the Turkish gunners gave the besieged no respite. Day and night the bombardment continued, until dawn of the 2nd of August when the Turks began to move forward with all the batteries opening up at once. So great was the noise the inhabitants of the southern coast of Sicily, 70 miles away, heard the thunder of the guns. By far the heaviest bombardment of the siege, it seemed impossible to Mustapha that any man could live, let alone fight, in those two crumbling ruins in the headland. From every ridge and slope the Turks swept like a hurricane against the walls of the two garrisons. Attack after attack they were repulsed, and in the early afternoon Mustapha Pasha was forced to concede defeat once again and order his troops to withdraw. He decided to give his two targets a further five days' continuous bombardment before attempting the next assault.

There was still no sign of a relief force from Sicily. Inevitably the Turks would have time to throw the full weight of their army into the attack before help ever came. During this bombardment men, women, and children worked side by side with the soldiers to repair the breaches, rebuild the barriers in the streets, and manufacture incendiaries from the damaged guns and weapons. It was during this lesser bombardment that La Valette managed to send a further missive to Viceroy Don Garcia in Sicily.

The assault was renewed on the 7th of August. As the sun crested in the east, even the bravest of men might have felt his spirits sink. From every angle could be seen the standards of the Grande Turke flapping in the wind. The enemy announced themselves by cannon. The echo of guns had not died away before they fell on Birgu and Senglea simultaneously. Piali's troops attacked Birgu, sweeping over the ditch half-filled already with the rubble from the walls. Impatient for victory, they burst into a yawning breach and surged forward into what appeared to be an undefended space–only to be confronted by another interior wall! These inner walls had been built to run around the landward side of Birgu, so when the enemy breached the main wall they would find themselves trapped. The troops who had poured in through the outer breach now came under a withering fire from the garrison. Caught in that narrow corridor between the two walls, unable to turn back because of the weight of their numbers pressing relentlessly behind them, they were slaughtered in the hundreds.

Seeing the attack falter, the defenders, sword in hand, leapt from their retrenchments and turned the Turkish indecision into a rout. The enemy was entirely destroyed as they turned to flee over the ground slippery with the blood of their comrades, making Piali's assault a disastrous defeat for Islam.

Mustapha's forces seemed to be having more success at Fort St. Michael in Senglea. The weight of their numbers was beginning to take its toll. This was the moment when Mustapha's plan to attack both garrisons at the same time might show some success. The Grand Master could only look with dismay on the line of Turkish pennants along the ramparts of St. Michael, knowing full well he could not withdraw a single man from his own hard-pressed garrison to send to their aid.

The garrison of St. Michael was steadily pushed backwards. Suddenly, clear above the noise of battle, the Turks heard the signal to retreat, even though Senglea was just within their grasp! The beleaguered wall was abruptly deserted. The Grand Master and many others must have thought that the unbelievable had actually happened and Don Garcia de Toledo had landed with a large relief force. This was, in fact, the very message Mustapha had received. A horseman had spurred up from the Turkish camp at the The Marsa (see map) reporting that a large Catholic force had fallen upon the encampment and was putting every man to the sword. There was no large Christian force in Malta, except for the garrisons; Mustapha's natural assumption was that Don Garcia had taken him in the rear. Alarmed at the prospect of losing his base and suffering his lines of communications to be cut, he had instantly given the order to retire.

|

|

Once back at the Marsa, a grim and bloody sight met his eyes. Dead and dying lay in heaps among cut-down tents, mutilated horses, and burning piles of stores. The vast Turkish camp, full of their sick and wounded, had been practically razed to the ground. There lay the dead, and there the ruined camp, but there was no sign of a large Christian force.

Mustapha Pasha mulled the event with growing anger. Once he learned the truth, his rage was uncontrollable. He tore his beard, forgot the men dead at his feet and thought only of the victory that had been snatched from his hands. Earlier that morning, the Chevalier Mesquita, Governor of Mdina, had heard the bombardment and guessed a major assault against the two garrisons to be well underway. Calculating that the Turkish camp would only be lightly guarded, he had dispatched his entire cavalry force to the Marsa. In the first charge they overwhelmed the sentries, killed every man they could find, captured or killed the Turkish horses, and destroyed the huge store of provisions. Mustapha quaked at the prospect of reporting his losses to the Sultan.

There was still no sign of a relief force, not even a message to give some hope to the defenders of Malta. The knights seemed to have been abandoned by the very Christendom they were defending. "When the Council meets tonight," Valette told Sir Oliver Starkey, "They must be told that there is no more hope of a relief force. Only we ourselves can save ourselves." While the Turkish army could revive their strength and morale in the relative security of their trenches, the defenders had not a moment's respite. Amid the shambles of their houses, they worked day and night to maintain their disintegrating fortress.

That night the Sacro Consiglio assembled. They knew that a messenger had arrived from Sicily, and they hoped for good news. The Grand Master did not mince words:

I will tell you now openly, my brethren, that there is no hope to be looked for except in the succor of Almighty God-the only true help. He who has looked after us until now, will not forsake us, nor will he deliver us into the hands of the enemies of the Holy Faith. We are soldiers and we shall die fighting. If, by any evil chance, the enemy should prevail, we can expect no better treatment than our brethren who were in St. Elmo....Let no man think that there can be any question of receiving honorable treatment, or escaping with his life. If we are beaten, we shall all be killed. It would be better to die in battle than terribly and ignominiously at the hands of the conqueror.

From that moment on there was no more talk of relief forces. Every man preferred death than to fall alive into the hands of the Turk. La Valette made use of a weapon now which he knew would strengthen the knights and Maltese alike. Pope Pius IV had recently promulgated a Bull which gave a plenary indulgence to all who fell in war against the Moslems. This being made known, "with the greatest devotion, with the firmest hope and faith that they would be received into glory, they resolved to die for their cause."

For the first time in the siege the Turks were driving mines beneath the defenses. At St. Elmo they had been unable to do so because of the hard rock on which the fort was built, but the soil of Birgu was more lenient. It had been mining that had won for the Turks at Rhodes, and they now attempted to repeat their success. This was a task of extreme difficulty and even the specially trained Egyptian engineers found themselves faced with an almost insuperable problem. The soil of Malta lies six feet deep at most, with sand and limestone beneath; when quarried this could be cut quite easily, but was incredibly difficult to tunnel through at short notice. While the sappers worked underneath, the batteries continued to harass the Christian defenses from Mt. Salvatore and the far side of Kalkara Creek (see map).

Mustapha's plan was to explode the mine beneath the Bastion8 of Castile at the same time as launching a large assault on Senglea. He had a large siege engine constructed as he waited for the mining to be completed. By the 18th of August the report came in that the head of the mine was finally under the Bastion of Castile and that its implosion would be sufficient to successfully bring the ramparts down. All was in order for Mustapha's next attack.

Although La Valette had known that the Turks were mining towards his walls he had been unable to locate their exact position. With a gigantic rumbling crash, the mine went up and a great section of the main wall caved in. Before the shock could register, Piali's troops attacked full-force. The explosion had caused the defenders to stagger back from the breach and in the general confusion it seemed as if the position was surely lost. The first wave of Turks over the ditch were able to gain a slight foothold.

La Valette seized a pike from a soldier standing nearby, called on his staff to follow him, and rushed boldly from his post of command in Birgu towards the Bastion of Castile. The Maltese, inspired by his leadership, joined in the change. Seeing the Grand Master at the head of a small group of knights running towards the point of danger, the disheartened soldiers forgot their fear, and with the Grand Master in the lead the tide was turned.

Suddenly, a grenade striking the ground nearby injured La Valette in the leg. The cry went up, "The Grand Master is in danger!" From every side knights and soldiers came rushing to the attack. The Turkish vanguard staggered back and began to yield. "Withdraw, Sire, to a place of safety!" shouted one of his staff. "The enemy is already in retreat!" Although this was true, the Turks still occupied the breach. La Valette knew his presence alone put new heart into the garrison, and now was not the time to forsake his men. Limping, he went forward up the slope. "As long as their banners still wave in the wind," he said, "I will not withdraw."

Knights, soldiers and Maltese from Birgu now surged forward with renewed energy, and within a few minutes the enemy was routed. Not until he had seen the whole bastion reoccupied and the defenses re-manned did La Valette concede to retiring to have his wound dressed. He knew that such a successful breach on the part of the Turks would lead them to attack again, quite possibly that same night. Indeed his conjecture was proven true when Mustapha and Piali renewed the onset shortly after dusk.

It was a night without darkness. The rippling flash of gunfire lit up the waters of Grand Harbor as the rumble of cannon echoed like thunder off the hillside. Silhouetted in the breach, the figure of the Grand Master was but a rock around which the storm raged, a constant visual encouragement for all his men. Dawn finally came, and the Turks withdrew with the two fortresses still in Christian command.

Mustapha now placed his hopes in the siege tower, knowing the Knights could not possibly withstand it. It was protected against incendiaries by great sheets of leather which were kept constantly soaked with water, making it impregnable to anything but fire. It was now so close to the wall that from its top platform Janissaries were beginning to pick off the defenders within Birgu. La Valette made its destruction his personal concern.

One can only conclude that La Valette received divine help in formulating his responses to every stratagem devised by the enemies of God. He ordered a band of Maltese workmen to burrow a hole in the base of the wall just opposing the tower and wheel a large cannon to face it, while workmen knocked down the outside blocks of the tunnel. Aloft in their high tower, the Turks had no idea of what was happening directly below them.

The dark muzzle of a cannon was run out and fired chain-shot which consisted of two large cannon balls fastened together by chain. Immediately on leaving the cannon's mouth, the chain-shot whirled in a parabola, acting like a giant scythe. At point blank range, this whirling chain sliced, pulped, and pounded the wooden structure. The vast erection sagged and buckled as Janissaries leapt from its heights. Finally, emitting a groan, it collapsed with a thunderous crash, spilling men, arms, ammunition, pitchers of water and incendiary grenades in all directions. The men ran the cannon back inside the fortress and the Maltese work party immediately started to restore the outer wall. As they watched the giant tower be set on fire, the Moslem leaders were almost despondent. It was becoming more and more difficult to induce their men to attack; sickness was spreading and ammunition and provisions were beginning to run low. Their will to fight was dampened by their numerous losses.

On the 20th of August, the Turks brought up another siege engine against the breached Bastion of Castile. Manned by Janissary snipers, the base of the tower had been reinforced with earth and stonework to forestall a repetition of previous events. These snipers began to pick off the remaining contingent on the other side of the ruined walls, and as the defenders began to falter, La Valette realized that if the tower were to remain there, keeping the garrison pinned down, a further frontal assault on Castile would almost inevitably succeed.

As before, he ordered the Maltese workmen to open a way through the wall at the base, at a point where they could not be seen by the Janissary snipers. The moment that the last blocks fell away, a raiding party made straight for the tower. Never expecting that the defenders would venture outside the walls–and prepared for cannon shot only–the Turks were taken completely by surprise. Clambering up the tower, with the stone base giving them easy access to the lower reaches, the soldiers swept up the laddered floors, killing the Janissaries with a few deft blows.

The siege engine now served another purpose. A picked troop of gunners with two cannon were established in it and protected by a band of knights and men-at-arms. The Turkish tower was now turned into a new vantage point for Castile, increasing their fire power against enemy attacks. With the now-humiliated Turks still numbering in the thousands and the defenders merely in their hundreds, it was obviously the invincible morale of the Christians which lent them such superiority, along with La Valette's stellar Catholic action, military genius, and ability to find an instant riposte to any ruse the Moslems might concoct.

Mustapha Pasha's dark mood deepened when he learned that a large store ship coming from North Africa to replenish their diminishing supplies had been captured by a Christian galley. Gunpowder was running short, and the Turks were now forced to husband their fire. Even though it was the third month, the island remained uncaptured. The Sultan Suleiman, however, was not a man to suffer failure easily. Rather than face the wrath of Suleiman, Mustapha thought of wintering in Malta and renewing the assault in the spring. It would be essential for him to capture Mdina to use as winter quarters and to obtain its guns, powder and shot to use against the knights in their strongholds. If worse came to worst and he was compelled to withdraw from Malta, it would still be to his credit if he could storm and capture the island's capital.

Mustapha suspected Mdina's garrison would be small. Since Don Mesquita, the Portuguese Governor, had sent most of his best troops down to Birgu at the beginning of the siege, the city was mainly composed of Maltese peasants and their families. Knowing the Turks to be greatly demoralized, he had the peasants dress in soldiers' uniforms and patrol the ramparts in company with the real garrison troops. All his available cannons were also readied and brought to the side from which the Turkish troops would certainly approach.

As the first of the invaders toiled up the long slopes towards the old city, what a sight met their eyes! This was no defenseless town with a weak garrison. The walls bristled with armed men; even before they came in range the guns began to thunder, as if to flaunt their anticipation of battle. The Turks were dismayed, and halted in consternation. The word flew back, "It is another impregnable position! Another St. Elmo!" Scouts circled the city and returned with reports of walls crowded with fighting men, fresh and eager to gain glory. Gutted of all ambition, Mustapha called off the attack. Don Mesquita gave thanks to God...with no more than a handful of trained soldiers in the city, very little powder and even less shot, they had outwitted the great Mustapha Pasha. A thanksgiving Mass was at once celebrated in the old cathedral.

The confidence of the knights was steadily increasing. Unknown to them, the long-delayed relief force was anxiously awaiting to depart from Messina, Sicily. This force was composed of professional soldiers and adventurers from all over Europe, mainly from Spain, but with many Italians, Germans, French and other European nations as well. Viceroy Don Garcia himself was in command of the force, and in the last week of August he set sail with close to 10,000 men in 28 ships, only to run into a severe gale. They headed for Malta at last on the 5th of September.

Meanwhile, the siege wore on, with the Turks launching one more attack on the 1st of September. The troops were so drained and disheartened, however, that it failed. Not only had the prolonged resistance of the garrisons served to drain the Moslems' morale, but dysentery, and enteric fever greatly enfeebled them and reduced their numbers. "It is not the will of Allah that we shall become masters of Malta," began the superstitious rumor.

The first ships of the relief force were nearing Gozo. It is one of the mysteries of the siege that no attempt was made to attack this spearhead of Christian ships. Perhaps Piali's captains, not liking the look of the weather, had abandoned the Gozo patrol and taken shelter. The news of Don Garcia's arrival reached Mustapha Pasha and La Valette at the same time. As Mustapha's army was on the verge of mutiny, he immediately ordered evacuation from the island.

Don Garcia wasted no time on the island, since a further reinforcement of 4,000 men were still waiting in Messina to come to the aid of their fellowmen. The joy of the Catholics and the despair of the Moslems were both unbounded. The very fact that the Viceroy's galleys could be at sea just off the harbor mouth and meet with no opposition proved that the Turkish fleet had lost the will to fight. All night long, the lights and flares along the shore illumined the retreating boats of the Islamic forces.

The relief force, meanwhile, established contact with the garrison in Mdina. The first Turkish ships were well under way, driving out past the ruins of St. Elmo. If the Moslems had lost the will to fight, La Valette certainly had not. Light cannons were rushed to St. Elmo and fired upon the retreating fleet, just as they had fired upon it when first it sailed imperiously into Grand Harbor almost four months before.

The siege was raised on the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The bells of the Church of St. Lawrence rang out over the shattered houses of Birgu, giving thanks to her for their victory. An eye-witness remarked, "That morning, when the bell rang for Mass, it was at the same hour that we had grown used to expect the call to arms. All the more solemnly then, did we give thanks to the Lord God, and to His Blessed Mother, for the favors that they had poured upon us."

Through the narrow streets lined with ruins, the victors made their way to offer their Te Deum to the God of Victories. The island still smoked and crackled from the fierce bite of war, but in the cool darkness of the small conventual church there was peace and quiet. As they entered and saw the gleam of the silver reliquary containing the hand of St. John the Baptist, they knew their dead brothers had not perished in vain.

At this very moment, while the survivors of the siege were giving thanks for their victory, Mustapha Pasha discovered that he had been tricked into believing the relief force to be double the 10,000 they actually were. Desperate to avoid the wrath of Suleiman, he stubbornly ignored Piali and ordered his balking army ashore again.

When the news of the Turks' return reached the Knights, the troops from Sicily, disappointed to not have been able to fight for the Faith, now bore down upon the Moslems. They engaged in fierce battle, slaughtering 3,000 of Mustapha's army, and driving the remainder to sea. Mustapha would have nothing now to present in his favor to Suleiman.

The Grand Master and his Council now took the time to take stock of what had befallen them. Nearly 250 knights of the Order had lost their lives, and those remaining were badly wounded or crippled for life. Of his original 9,000, the Grand Master had barely 600 left still capable of bearing arms.

The Turks had lost 30,000 men. Mustapha Pasha and Piali may well have trembled for their lives when they returned in defeat to Constantinople. Suleiman's rage was extreme, but he spared their lives. "There is not one of my officers whom I can trust!" he cried. "Next year, I myself, the Sultan Suleiman, will lead an expedition against this accursed island. I will not spare one single inhabitant....! see that it is only in my own hand, that my sword is invincible." The expedition did not take place, and in the following year he turned his attention to the war in Hungary where he died (1556) at the age of 72. In the course of a long reign, perhaps the most glorious period in the history of Islam, he had only met with two defeats. The one was his failure before the walls of Vienna in 1529, and the second–and by far the most damaging–was at Malta. This was the last formal attempt made by any leader of the Ottoman Empire to break into the western Mediterranean, and it was the defeat of his army in this great siege which first checked the westward expansion of Turkish power.

Honors were showered upon the Grand Master La Valette by all the kingdoms of Europe. The effort of the Knights to maintain Malta as their home was not dampened by the havoc of that summer, and for the remainder of 1565, they labored to repair the defenses lest another siege might follow. Such was the prestige of the name of La Valette and the fame of the island that financial contributions abounded, thus enabling the galleys of the Order to be restored and ready by the following year for the lucrative task of raiding the Sultan's supply lines.

In December of 1565, the Italian engineer Francesco Zaparelli, especially appointed by the Pope for the task, reached Malta with plans for a new city. Located on Mt. Sciberras, the new citadel was christened Valetta and is now among the most magnificent cities in Europe, and certainly the greatest surviving fortress from those troubled times. Its massive walls and magnificent churches are impressive, as is the co-cathedral of St. John, described by Sir Walter Scott as "the most magnificent church in all of Europe."

La Valette died three years after the siege, on August 21, 1568. In his final deposition, he appealed to his brethren to live together in peace and unity, and to uphold the ideals of the Order. He now lies in the great crypt of the Cathedral of St. John. At his side rests Sir Oliver Starkey, his faithful friend and secretary, the only other man to be buried in the crypt. The inscription upon La Valette's tomb, composed in Latin and written by Sir Oliver Starkey, reads:

Here lies La Valette, worthy of eternal honor. He who was once the scourge of Africa and Asia, and the shield of Europe, whence he expelled the barbarians by his holy arms, is the first to be buried in this beloved city, whose founder he was.

Around him lie the Grand Masters who were to follow him in later centuries. Above, on the tesselated floor of the great cathedral, shine the arms and the insignia of the knights who, for more than 200 years, were to maintain the impregnable fortress of Valetta.

This article was part of a conference given at the Dietrich von Hildebrand Institute 2002 Summer Symposia entitled "The 1st Through 8th Crusades; Military Orders; Catharist Crusade; and the Siege of Malta" by Michael Davies. Tapes of this conference (5 cassettes) will be available from the Dietrich von Hildebrand Institute. Please visit http://www.romanforum.org/tapes.php for more information or write to the Institute at 11 Carmine Street #2C, New York, NY 10014. The conference was adapted and edited for The Angelus by Miss Clare Lindsey Carroll.

1. corsair: a pirate from the Barbary coast.

2. galliot: a small, swift galley, formerly used in the Mediterranean.

3. culverin: medieval cannon of relatively long barrel and light construction. It fired 8- to 16-pound projectiles at long ranges along a flat trajectory. It was adapted to field use by the French in the mid-15th century and to naval use by the English in the late 16th century.

4. basilisk: ancient brass cannon.

5. Marsa: In the inner part of the Grand Harbor there are the well-protected creeks of Marsa, an important place since olden times. The low-lying areas collected dirty stagnant water that caused many cases of malaria and dysentery. This area was where the Turks pitched camp for the duration of the Siege of Malta in 1565.

6. ravelin: A detached triangular fortification consisting of two embankments which make a salient angle.

7. arquebus (Spanish): a European matchlock gun, an obsolete firearm with a long barrel.

8. bastion: projecting part of a rampart or other fortification.