The Spirit of Illuminated Color

Gerald L. Browning

The Production of Religious Stained Glass

In the first century A.D., the Roman scholar Pliny related how glass was first recognized by Phoenician merchants sitting around a campfire on a tidal river in Syria. The soda blocks they used to support their cooking pots had melted and solidified into a hard, shiny mass.1 Egyptian antiquity is rife with descriptions of artisans producing small glass cylinders by a refined cooking, blowing, and annealing (cooling) process.2 The Romans experimented with various techniques for making glass including casting and spinning.3 Glass panes have been found in the ruins of Pompeii.4 Colored mosaic panels covered most of the inner surfaces in the beautiful Byzantine church of Sophia Hagia in Istanbul in the 5th century.5 Dionysius, a monk living during this period, wrote in his work Heavenly Names and the Celestial Hierarchies that "light...was the main constituent of matter. All was made of light."6 The belief that light had a tangible mass was part of the Aristotelian philosophy of the nature of all things. In the 10th century, colored glass panels were known to exist in the monasteries of Monte Casino and Rheims.7 The Abbot Gozbert, writing from Tergensee in the late 10th century, described how "the golden-haired sun could now for the first time, shine upon the pavement of our church through glass painted with pictures in various colors."8 By 1100, the stained glass art form had become well established in Europe. Its development coincided with other religious art forms such as manuscript illumination, jewel embossment, and parchment gilding, which were in their infancy. Enameled reliquaries, carved ivories, and colored tapestries became the inspiration for the glass.9

The purpose of this article is twofold. One is to study the French artists at Chartres who produced beautiful panes of glass in the 13th century. The other is to place the glass within the religious context of Thomistic philosophy, one grounded in the principles of faith and reason. The glass makers toiling arduously at their craft were the unwitting transmitters of a religious philosophy intended to produce art for the masses. It was an art that allowed people to see what they could not read. This was the message of God, delivered in the translucent gloom of a great church, reflected in a spectrum of colors spilling out of the naves and transepts, and settling like heavenly dust on all who walked within.

THE CATHEDRAL

The village of Chartres looks today much as it looked 800 years ago. Set in the undulating plains of France's wheat region, it sits on a slope overlooking the Eure River. In summer, the blazing yellow light of the wheat shimmers as the wind passes over it. In winter, the fallen stalks hug the earth, forming a golden carpet. A traveler approaching Chartres from a distance is struck by the sudden appearance of the great steeples. The church seems to envelop the city like a great bird spreading its wings over its nest. The farmers, artisans, and shopkeepers of the time were all living amidst this awesome beauty. No wonder Rodin called it the "Acropolis of France."10 The fate of the first church at Chartres built during the 4th century is not known. The Normans destroyed a second church in 858. Bishop Fulbert built the first cathedral in 1020. It was probably during his time as bishop that stained glass made its appearance in the form of 25 windows purchased and arranged by the church. Three of these survived the great fire of 1194. From 1194 to 1212, the current massive stone cathedral was erected and during the next 25 years, the 175 windows were made and installed.11 Finally, about 1240, the cloister for the housing of the clergy was constructed, and it included the lovely gardens and walking paths of the Bishop's palace.12 The support for the construction of the church at Chartres was the result of a broad-based community effort involving clergy, noblemen, tradesmen, and the general populace. The church reflected the love of the people for their God, Faith, and city. Often they would sing and pray at night, next to their carts and coaches as they watched the spires gleam against the moonlit sky. Rene Jacques, in his work French Cathedrals, viewed the church as the "sum of theological knowledge."13

Scholars credit Abbot Suger of the royal abbey at St. Denis near Paris with providing much of the theological inspiration for the production of the glass at Chartres. Suger was closely associated with the French monarchy through his childhood friendship with Louis the Fat. Suger believed that "only the best objects that man could create were worthy of the house of God"14 The glass should be a receptor for God's light, a form of apprehending it. Suger was concerned with creating what Reyntiens described as an "atmosphere" by reducing stonework and adding glass.15 The costs were apparently of little consideration since guild or craft consortiums underwrote many of the windows. Suger understood that the Gothic style of architecture, with its vaults and buttresses, could sustain heavy loads and heights of stone on glass. He commissioned the work of many traveling groups or studios of craftsmen who produced a wide array of styles and color schemes for the new windows. Suger saw the result as a brilliant panoply of light, living as a colored membrane. For Suger, the windows would become a mystical experience. For the common people, the windows were much more utilitarian, because, as Suger noted, they showed "people who could not read what they must believe."16 Guilds joined with craftsmen and merchants in making sure they were represented in the church. Shoemakers, winemakers, and carpenters were all given a window alongside that of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. The windows merged into a statement of form and substance, faith and reason, and became what one noted art historian has called the Biblia pauperum or "Bible of the Poor."17

FAITH AND REASON

Stained glass was the product of a vibrant Catholic Faith that had its origins in Jesus Christ and the theology of the early Catholic Church, especially in the writings of the Doctors like St. Augustine. St. Augustine wrote often of the spiritual power of light. He describes a powerful sermon delivered by St. Ambrose, his teacher, during a particularly treacherous period of Catholic persecution in Milan:

And all our minds from anguish ease,

and our distempered grief appease,

that so when shadow round us creep,

and all is hid in darkness deep,

faith may know of gloom,

and night borrow from faith new gleam, new light.18

St. Augustine wrote, "The Bible is what God has kept from the wise and revealed to the simple and innocent."19 The colored light of the great cathedral would illuminate all classes of men, regardless of their origins. St. Augustine's use of the word "light" as a medium of spiritual uplifting is found often in his work The City of God. For example, he describes light as "the intelligible illumination of truth."20 Men working in the sweltering heat, odors, and fumes of the glass furnaces became the transmitters of this new light. Unlike their brethren in the monastic scriptoria, who often toiled in the obscurity of cold, dark, fortresses, and whose books were usually enjoyed by a select group of clerics, the craft of the stained glass illuminator was for everyone to see and enjoy.

The stained-glass makers were special men. One can imagine them working, in their leather aprons with long, hot iron tongs in their thick callused hands, lifting the molten glass from its firing bin, gently rolling it into patterns, and then passing it on to an artist who engraved and painted the colorful scenes. The glass was their canvas, and the church became their display scene. Not all glass makers probably reveled in the beauty they had created. For some, it was perhaps just a job, a way of taking care of heir families. We know that many of the craftsmen were itinerant workers moving from place to place who might never see their finished product. For the people of Chartres, however, the glass glorified what Ian Barbour, in his work Science and Religion, has called "humanity within the cosmic drama."21 The coalescing of religious faith and human technology reflected the philosophical vision of medieval scholasticism. Except for its twin spires, Chartres was completed in 1260, but later, in his Summa Theologica, St. Thomas Aquinas examined the essence of light as a visible form through which color could be actualized. He spoke of light as "an active quality consequent on the substantial form of the sun."22 Aquinas wrote: "Now the act of power using a bodily organ depends...on the power of the soul, but also on the disposition of the bodily organ, just as seeing depends on the power of sight...and upon the condition of the eye."23

St. Thomas allowed for the division of light into two spheres, the created light of the human intellect and that of the divine supernatural. Created light helps man understand the physical and natural truths that guide his existence. The glass at Chartres was a conduit for the transference of divine grace in the form of light into the mind of man.24

In his work Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism, Erwin Panovsky noted that both architecture and philosophy were able to merge comfortably into a unity of being that resulted in a beautiful church like Chartres.25 He described this unity as "impartens ordinem ad actum" or "bringing order to action"26which is the virtue of art.

Scholasticism incorporated a sense of reason into the production of the glass. Not all glass makers were spiritually inspired, but their craft necessarily adhered to principles of reason. Panovsky described how the glass contained a "visual logic" that insured stability.27 The individual pieces together formed a holistic panel of interrelated arrangements, upholding the mathematical principles that allowed for the glass to hold up the stone loads. A balance was achieved between glass and stone. John James, in his book Chartres, called it a "dynamic equilibrium."28 Panovsky summarized:

To him [St. Thomas Aquinas], the panoply of shafts, ribs, and buttresses, tracery, pinnacles, and crockets was a self-analysis and self-explication of architecture, much as the customary apparatus of parts, distinctions, questions, and articles was to him, a self-analysis and self-explication of reason.29

THE GLASSMAKERS

The glass making studio of the 13th century was a bustling center of activity. Bellows pumped air into the hot smelting furnaces tended by men constantly stuffing beechwood logs into it. Their brows dripped with a dirty sweat, the result of the thin film of soot that seemed to stick to the air. In other parts of the room, men worked–blowing, rolling, and flashing glass. Still others labored at various tasks such as cleaning, glazing, and leading. Finished pieces of glass in various shapes and sizes were stacked everywhere. Some were colored in brilliant tones. Others were of a dull, yellow tint. Workers selected glass for the inscribing of scenes and figures, or for the final process of painting. The process was organized and efficient. Each worker had his role in producing a window that would become part of the mullions, transoms, and tracery of the great church.30 The early medieval glass makers seemed more like chemists than craftsmen. They mixed the soft, quartz-like sand with soda ash, lime, or potash, gradually turning it into a mushy paste. They fretted over the sand because it had to be pure and clean. Usually, they were able to find it on the banks of the Eure River.31 They might add a dash of powdered cobalt or copper oxide or even perhaps some vegetable matter such as yams or potatoes, the moisture of which would bubble, giving the glass a murky, uneven appearance.32 They might even add sugar, which, when melted, gave the glass a wonderful amber tint. Some glass makers were famous for their recipes, understandable since the color was critical for the final product. Each color reflected some spiritual entity or concept. The Virgin Mary was usually shown in blue, white, or gold. Green indicated nature; brown and gray symbolized earth; and purple represented nobility. Ruby reflected blood and was important because its recessive nature kept other colors from dominating it. White or clear glass was important for tempering the background effect of blue.33 Much of what is known about 13th-century glass making has been chronicled by the obscure German monk Theophilus who wrote about a variety of medieval art forms including painting, metalwork, and enamels. From Theophilus we learn that the furnaces for cooking glass were large, rectangular kilns, some having a cooking surface of 100 square feet or more. They were made of three to four layers of stone and clay about four feet high with arched vaults for placing and removing the pots of bubbling glass. The bottom contained the firing chamber for burning beechwood, the most common fuel.34 Later, the wood ash was mixed with the sand, turning it into a mushy porridge. Through an elaborate process of cooking, annealing, and frittering (simmering), the raw product was produced. Then pigments usually were added, perhaps powdered iron or manganese that had been ground together in wine or urine.35 After another period of simmering, the glass was then blown into a large bubble by using a thin, iron blowpipe. Theophilus reminds us that the blower had to be careful not to suck in the hot fumes from the glass.36 The gob of glass, once it was spun, resembled what Rogers and Beard have described as an "undulating, thick skinned bubble or sausage" moving "lazily as the pipe is twisted or swung about."37 The "gaffer" then took the gob and re-cooked it until it was ready for the cooling and rolling process. Eventually, the slitter or cutter sliced the flattened sheet of glass on a wooden platform using a hot crozing iron.38 By tracing the line of cut with urine or spittle, he could prevent the glass from splitting in different directions.39 This process was also used in cutting specific shapes. First, the glass maker drew the figures on a wooden board covered with water and chalk. Then he carefully laid the glass sheet on the board, tracing the design with a brownish-red enamel known as grisaille.40 The brush was made from donkey or horsehair, although finer-haired brushes made from sable or camel hair were used later for more elaborate coloring. The pieces were then reheated and cut using the wine and urine method. Finally, the drapery folds, facial features, and natural scenes were painted in, much like a child might paint a cartoon puzzle. This finished "cartoon," now covered in beautiful variations of color, was baked again.41 The assembly of the windows was painstaking. Each piece was edged in a soft stick of lead solder that would act as a caulk. The usual mixture was five parts of pure tin to one part of lead. The pieces of glass were held to the board by butterfly nails. The joints were smeared with an iron flux and then melted with a hot iron. The glass pane, when cooled, was then turned over and the process was repeated.42 The finished pane was set into a lead frame which had been stretched to the proper size in a vice.43 The masons prepared the mortar and stone inside the church for the arrival of the glass. They worked with amazingly simple tools such as string lines, rules, compasses, and dividers. They chiseled and smoothed the interior edges of the walls and moldings, and then set the wrought iron casings in place with mortar. Each casing was routed so that the glass pane would fit snugly in place.44Transferring it to the outside buttresses had already solved the problem of load bearing. The glass did not have to bear the strain of holding up the tons of purple limestone because a balance had been created between the outside flyers and the walls. The glass had only to look beautiful. John James called it "a thin skin of wall"...whereby "glass predominates, not the masonry."45

|

|

THE WINDOWS

When the 175 windows at Chartres were completely installed in 1240, they represented a biblical and human document. The townspeople were noticeably proud of their masterpiece. They must have enjoyed admiring the specific panes of daily life. For the purpose of clarity and illustration, three of the panes shall be viewed through the eyes of the craftsmen at Chartres.

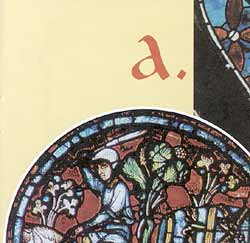

The North Rose Window with the Detail of an Angel (Fig. A) is one of deep blues, reds, and a solid black background. The newly arrived winged angel is standing on the wheel of life, his arms outstretched in welcome. His feet are perched on a smaller wheel, which appears to be turning. His eyes look outward, into the distance, and his wings are taut and straight like a bird landing on water. Behind his stunning red halo are the green leaves of life. Around him are other circles in rose petal motifs, perhaps indicative of the flow of Jesus' blood. From a structural perspective, the pane shows the use of leading in developing a composite picture. The use of vertical and horizontal bars of lead is important in giving the glass stability. They contrast with the circles and petals that surround this remarkably human depiction of an angel.

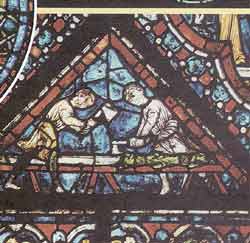

The Noah Window (Fig. B) is a stunningly beautiful example of the integration of many colors into a window. Every color known to the glass maker is used, including the tinted yellow grisailles, which were intended to provide balance to the darker colors. Darker colors predominate in order to give an impression of mystery. In this pane, the blue forms a bright background for the men working assiduously at their task. They are set within an enclosed triangular area, perhaps symbolically sculpting the keel sections for the great ark. The triangle looks surprisingly similar to the inside of a ship, as if the men were working below deck among the beams and knees.

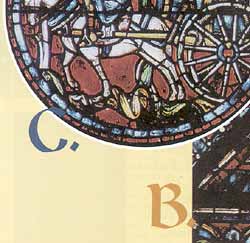

The St. Lubin Window (Fig. C), with its detail of a wine cart, is an example of the intricate nature of the glass maker's skill. The pane has been colored mostly in reds, perhaps revealing the type of wine made by the patrons of the window. The wine barrel tied to the cart signifies the pale blue color of young grapes. Green vines seem to grow out of the barrel. The blue-clad winemaker, obviously the centerpiece of the panel, sits dominantly on his weary white horse with his whip in hand. The scene is an expression of God's desire to see man enjoy nature, to use the fruits of the earth. Around the winemaker are scenes of everyday life set in the realistic form of a great church.

CONCLUSION

There is an interrelationship of the humanities and technology to produce religious stained glass. One is not possible without the other. This coalescing of a human craft with the Gospel of Our Lord Jesus Christ resulted in something of earth–beautiful and joyful for humanity–and something that glorified God.

Mr. Browning is a retired high school history teacher (31 years). His undergraduate and master's degrees are in American History. He taught Ancient and European History for many years at the college level in an adjunct role. He is presently an instructor in Western Civilization at the Community College of Rhode Island, and is pursuing his doctoral studies. He is married with three children.

1. Beard & Rogers, p. 2.

2. Judson, p. 4.

3. The Technique of Stained Glass Art, p. l.

4. Huether, p. 40.

5.Ibid., p. 48.

6. Peter Reyntiens, p. 19.

7. Shinfield, p. 6.

8. Beard & Rogers, p. 158.

9. Peter Reyntiens, p. 24.

10. Monmarche, p. 6.

11. The Blue of Chartres, p. 1.

12. Monmarche, pp. 54-55.

13. Jacques, p. 8.

14. Lawrence, Seddon, and Stephens, p. 68.

15. Peter Reyntiens, p. 25.

16. Ward,p. 53.

17. Judson, pp. 6-7.

18. Fulop-Miller, p. 123.

19. Ibid.

20. Augustine, pp. 873-74.

21. Barbour, p. 8.

22. Aquinas, 1981, p. 336.

23. Aquinas, p. 155.

24. Ibid., p. 154.

25. Panovsky, p. 4.

26. Ibid., p. 20.

27. Ibid., p. 58.

28. James, p. 5.

29. Ibid., p. l75.

30. Panovsky, p. 59.

31. Heuther, pp. 12-13.

32. Beard & Rogers, p. 17.

33. Judson, pp. 12-13.

34. Theophilus, pp. 49-51.

35. Ibid., pp. 52-53.

36.Ibid., pp. 54-55 .

37. Beard & Rogers, p. 10.

38. Ward, p. 53.

39. Leathaby, p.49.

40. Beard & Rogers, p. 163.

41. Monmarche, p. 72.

42. Theophilus, p. 71.

43. Patrick Reyntiens, p. 111.

44. Merlot, p. 48.

45. James, p. 10.

Picture

Picture

Print Sources

Aquinas, St. Thomas. Summa Theologica, Vol.1, trans. Fathers of the Dominican Province. Westminster, Maryland, Christian Classics, 1981.

Aquinas, St. Thomas. Treatise on Happiness, trans. John A. Oesterle. Englewood, N.J.: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1964.

Augustine of Hippo. City of God, trans. Henry Bettenson. London: Penguin Books, 1972.

Alice Beard & Francis Rogers. 5000 Years of Glass. New York: J.B. Lippencott, 1948.

Barbour, Ian. Science and Religion. 1997.

Brisac, Catherine. A Thousand Years of Stained Glass, trans. Geoffrey Culverwell. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1986.

Fulop-Miller, Rene. The Saints that Moved the World: Anthony, Augustine, Francis Ignatius, and Theresa. London: Thomas Y. Cromwell, 1945.

Huether, Anne. Glass and Man. Philadelphia: J.P. Lippencott Company, 1963.

Jacques, Rene. French Cathedrals. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co. Inc., 1959.

James, John. Chartres. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1982.

Judson, Walter W. Introduction to Stained Glass. Los Angeles: Nash Publishing, 1972.

Lawrence Lee, George Seddon, and Francis Stephens. Stained Glass. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1976.

Letherby, W. R. The Artistic Craft Series of Technical Handbook on Stained, Glass Work. London: John Hogg, Publisher, 1905.

Merlet, Rene. The Cathedral of Chartres. Paris: Henry Laurens, Edition, 1915.

Monmarche, Georges. Chartres, Paris: Alpina Editions, 1950.

Panovsky, Erwin. Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism. Latrobe, Pa.: The Arch Abbey Press, 1948.

Reyntiens, Patrick. The Technique of Stained Glass. New York: Watson, Gupstill Publications, 1972.

Reyntiens, Peter. The Beauty of Stained Glass. London: Little, Brown and Company, 1990.

Shinfield, Margaret. Medieval Stained Glass. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1964.

Theophilus. On Diverse Arts, trans. John G. Hawthorne and Cyril Stanley Smith. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1979.

The World Atlas of Architecture, ed. Christian Flon, trans. Christopher Dufton, et al. London: Mitchell Beazeley Publishers, 1984.

Ward, Colin. Chartres: The Making of a Miracle. London: The Folio Society, 1986.

Internet Sources

Great Buildings/Stained Glass (2001), Available: http://www.greatbuildings.com/gbc.html.

The Blue of Chartres (2001), Available: http://www.chartres-csm.org/usfixe/vitraux/blue.html.

The Technique of Stained Glass Art (2001), Available: http://www.chartres-csm.org/us.html

Your Internet Home for Architectural Stained Glass (2001). Available: http://www.stainedglass.org/main_pages/association_pages/historySG.html